Computer Oral History Collection, 1969-1973, 1977

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computer Oral History Collection, 1969-1973, 1977

Computer Oral History Collection, 1969-1973, 1977 Interviewee: John H. Curtiss Interviewer: Henry S. Tropp Date: March 9, 1973 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History TROPP: This is a discussion with Professor John H. Curtiss in his office at the University of Miami in Coral Gables. Professor Curtiss is Professor of Mathematics here at the University of Miami. [Recorder off]. I guess the first question is really quite a general one and that is: You were in the Navy during the war and on leave of absence from Cornell as a mathematician. How did you end up at the Bureau of Standards? CURTISS: Dr. W. Edward Deming, who is one of my best friends in Washington, at that time was a senior adviser, statistical adviser, at the Bureau of the Budget -- was friendly with Dr. E. U. Condon. Dr. Deming, like some other great statisticians at the time and before, was himself a trained physicist. I believe Karl Pearson was a physicist and I believe also R. A. Fisher was a physicist; and naturally the physicists more or less knew each other, and so Dr. Deming felt that there should be a statistical adviser in the Bureau of Standards just as there was one in the Census Bureau -- that is, a person qualified statistically who had the ... who had publications and who might, say, be a Fellow of the Institute and the Association, just as Morris Hanson had the same qualifications for a parallel job with Census. I believe that Dr. Deming actually brought Hanson, Mr. Hanson, to the Census Bureau. -

Hannes Werthner Frank Van Harmelen Editors

Hannes Werthner Frank van Harmelen Editors Informatics in the Future Proceedings of the 11th European Computer Science Summit (ECSS 2015), Vienna, October 2015 Informatics in the Future Hannes Werthner • Frank van Harmelen Editors Informatics in the Future Proceedings of the 11th European Computer Science Summit (ECSS 2015), Vienna, October 2015 Editors Hannes Werthner Frank van Harmelen TU Wien Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Wien, Austria Amsterdam, The Netherlands ISBN 978-3-319-55734-2 ISBN 978-3-319-55735-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-55735-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017938012 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. This work is subject to copyright. All commercial rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. -

Projects and Publications of the National Applied

NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS REPORT 2688 PROJECTS and PUBLICATIONS « of the NATIONAL APPLIED MATHEMATICS LABORATORIES A Quarterly Report April through June 1953 <NBp> U. S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS U. S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Sinclair Weeks, Secretary NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS A. V. Astin, Director THE NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS The scope of activities of the National Bureau of Standards is suggested in the following listing of the divisions and sections engaged in technical work. In general, each section is engaged in special- ized research, development, and engineering in the field indicated by its title. A brief description of the activities, and of the resultant reports and publications, appears on the inside of the back cover of this report. Electricity. Resistance Measurements. Inductance and Capacitance. Electrical Instruments. Magnetic Measurements. Applied Electricity. Electrochemistry. Optics and Metrology. Photometry and Colorimetry. Optical Instruments. Photographic Technology. Length. Gage. Heat and Power. Temperature Measurements. Thermodynamics. Cryogenics. Engines and Lubrication. Engine Fuels. Cryogenic Engineering. Atomic and Radiation Physics. Spectroscopy. Radiometry. Mass Spectrometry. Solid State Physics. Electron Physics. Atomic Physics. Neutron Measurements. Infrared Spectroscopy. Nuclear Physics. Radioactivity. X-Rays. Betatron. Nucleonic Instrumentation. Radio- logical Equipment. Atomic Energy Commission Instruments Branch. Chemistry. Organic Coatings. Surface Chemistry. Organic -

Projects and Publications of the Applied Mathematics Division: A

Projects and Publications of the NATIONAL APPLIED MATHEMATICS LABORATORIES A QUARTERLY REPORT April through June 1949 NATIONAL APPLIED MATHEMATICS LABORATORIES of the NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS . i . NATIONAL APPLIED MATHEMATICS LABORATORIES April 1 through June 30, 1949 ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE John H. Curtiss, Ph.D., Chief Edward W. Cannon, Ph.D., Assistant Chief Myrtle R. Kellington, M.A., Technical Aid Luis 0. Rodriguez, M.A. , Chief Clerk John B. Tallerico, B.C.S., Assistant Chief Clerk Jacqueline Y. Barch, Secretary Dora P. Cornwell, Secretary Vivian M. Frye, B.A., Secretary Esther McCraw, Secretary Pauline F. Peterson, Secretary INSTITUTE FOR NUMERICAL ANALYSIS COMPUTATION LABORATORY Los Angeles, California Franz L. Alt, Ph.D. Assistant and Acting Chief John H. Curtiss, Ph.D Acting Chief Oneida L. Baylor... Card Punch Operator Albert S. Cahn, Jr., M.S ...... Asst, to the Chief Benjamin F. Handy, Jr. M.S Gen'l Phys’l Scientist Research Staff: Joseph B. Jordan, B.A. Mathematician Edwin F. Beckenboch, Ph.D Mathematician Joseph H. Levin, Ph.D. Mathematician Monroe D. Donsker, Ph.D Mathemat ician Michael S. Montalbano, B.A Mathematician William Feller, Ph.D Mathematician Malcolm W. Oliphant, J A Mathematician George E. Forsythe, Ph.D Mathemat ician Albert H. Rosenthal... Tabulating Equipment Supervisor Samuel Herrick, Ph.D Mathemat ician Lillian Sloane General Clerk Magnus R. Hestenes, Ph.D Mathemat ician Irene A. Stegun, M.A. Mathematician Mathemat ician Mark Kac , Ph.D Milton Stein Mathematician Cornelius Lanczos, Ph.D Mathematician Ruth Zucker, B.A Mathematician Alexander M. Ostrowski, Ph.D Mathematician Computers Raymond P. Peterson, Jr., M.A Mathematician John A. -

Projects and Publications of the Applied Mathematics

Projects and Publications of the NATIONAL APPLIED MATHEMATICS LABORATORIES A QUARTERLY REPORT October through December 1949 NATIONAL APPLIED MATHEMATICS LABORATORIES of the NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS : . .. NATIONAL APPLIED MATHEMATICS LABORATORIES October 1 through December 31, 1949 ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE John H. Curtiss, Ph.D., Chief Edward W. Cannon, Ph.D., Assistant Chief Olga Taussky-Todd, Ph.D., Mathematics Consultant Myrtle R. Wellington, M.A., Technical Aid Luis 0. Rodriguez, M.A., Chief Clerk John B. Taller ico, B.C.S., Assistant Chief Clerk Jacqueline Y. Barch, Secretary Dora P. Cornwell, Secretary Esther McCraw, Secretary Pauline F. Peterson, Secretary INSTITUTE FOR NUMERICAL ANALYSIS COMPUTATION LABORATORY Los Angeles, California J. Barkley Rosser, Ph.D Director of Research John Todd, B.S Chief Albert S. Cahn, Jr., M.S Assistant to Director Franz L. Alt, Ph.D Assistant Chief Arnold N. Lowan, Ph.D .... Consultant Research Staff Jack Belzer, B.A . Mathematician Forman S. Acton, Ph.D Mathematic 1 an Donald 0. Larson, B.S . Mathematician George E. Forsythe, Ph.D Mathematician Joseph H. Levin, Ph.D . Mathematician Magnus R. Hestenes, Ph.D Mathematic 1 an Herbert E. Salzer, M.A . Mathematician William Karush, Ph.D Mathematician Irene A. Stegun, M.A . Mathematician Cornelius Lanczos, Ph.D Mathematician Computing Staff: Alexander M. Ostrowski, Ph.D . Consultant Otto Szasz, Ph.D Mathematician Oneida L. Baylor Lionel Levinson, B. M.E. Wolfgang R. Wasow, Ph.D.*... Mathematician Ruth E. Capuano Dav IdS. Li epman Natalie Coplan, B.A. Michael S. Montalbano, B.A. Graduate Fellows: Bernard C. Dove Malcolm W. Oliphant, M.A. George E. Gourrich, B. -

A Reconstruction of the Mathematical Tables Project's Table Of

A reconstruction of the Mathematical Tables Project’s table of natural logarithms (4 volumes, 1941) Denis Roegel To cite this version: Denis Roegel. A reconstruction of the Mathematical Tables Project’s table of natural logarithms (4 volumes, 1941). [Research Report] LORIA, UMR 7503, Université de Lorraine, CNRS, Vandoeuvre- lès-Nancy. 2017. <hal-01615064> HAL Id: hal-01615064 https://hal.inria.fr/hal-01615064 Submitted on 13 Oct 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. A reconstruction of the Mathematical Tables Project’s table of natural logarithms (1941) Denis Roegel 12 October 2017 This document is part of the LOCOMAT project: http://locomat.loria.fr “[f]or a few brief years, [the Mathematical Tables Project] was the largest computing organization in the world, and it prepared the way for the modern computing era.” D. Grier, 1997 [29] “Blanch, more than any other individual, represents that transition from hand calculation to computing machines.” D. Grier, 1997 [29] “[Gertrude Blanch] was virtually the backbone of the project, the hardest and most conscientious worker, and the one most responsible for the amount and high quality of the project’s output.” H. -

Visiting Mathematicians Jon Barwise, in Setting the Tone for His New Column, Has Incorporated Three Articles Into This Month's Offering

OTICES OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY The Growth of the American Mathematical Society page 781 Everett Pitcher ~~ Centennial Celebration (August 8-12) page 831 JULY/AUGUST 1988, VOLUME 35, NUMBER 6 Providence, Rhode Island, USA ISSN 0002-9920 Calendar of AMS Meetings and Conferences This calendar lists all meetings which have been approved prior to Mathematical Society in the issue corresponding to that of the Notices the date this issue of Notices was sent to the press. The summer which contains the program of the meeting. Abstracts should be sub and annual meetings are joint meetings of the Mathematical Associ mitted on special forms which are available in many departments of ation of America and the American Mathematical Society. The meet mathematics and from the headquarters office of the Society. Ab ing dates which fall rather far in the future are subject to change; this stracts of papers to be presented at the meeting must be received is particularly true of meetings to which no numbers have been as at the headquarters of the Society in Providence, Rhode Island, on signed. Programs of the meetings will appear in the issues indicated or before the deadline given below for the meeting. Note that the below. First and supplementary announcements of the meetings will deadline for abstracts for consideration for presentation at special have appeared in earlier issues. sessions is usually three weeks earlier than that specified below. For Abstracts of papers presented at a meeting of the Society are pub additional information, consult the meeting announcements and the lished in the journal Abstracts of papers presented to the American list of organizers of special sessions. -

Projects and Publications of the Applied Mathematics

Projects and Publications of the NATIONAL APPLIED MATHEMATICS LABORATORIES A QUARTERLY REPORT April through June 1949 NATIONAL APPLIED MATHEMATICS LABORATORIES of the NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS . i . NATIONAL APPLIED MATHEMATICS LABORATORIES April 1 through June 30, 1949 ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE John H. Curtiss, Ph.D., Chief Edward W. Cannon, Ph.D., Assistant Chief Myrtle R. Kellington, M.A., Technical Aid Luis 0. Rodriguez, M.A. , Chief Clerk John B. Tallerico, B.C.S., Assistant Chief Clerk Jacqueline Y. Barch, Secretary Dora P. Cornwell, Secretary Vivian M. Frye, B.A., Secretary Esther McCraw, Secretary Pauline F. Peterson, Secretary INSTITUTE FOR NUMERICAL ANALYSIS COMPUTATION LABORATORY Los Angeles, California Franz L. Alt, Ph.D. Assistant and Acting Chief John H. Curtiss, Ph.D Acting Chief Oneida L. Baylor... Card Punch Operator Albert S. Cahn, Jr., M.S ...... Asst, to the Chief Benjamin F. Handy, Jr. M.S Gen'l Phys’l Scientist Research Staff: Joseph B. Jordan, B.A. Mathematician Edwin F. Beckenboch, Ph.D Mathematician Joseph H. Levin, Ph.D. Mathematician Monroe D. Donsker, Ph.D Mathemat ician Michael S. Montalbano, B.A Mathematician William Feller, Ph.D Mathematician Malcolm W. Oliphant, J A Mathematician George E. Forsythe, Ph.D Mathemat ician Albert H. Rosenthal... Tabulating Equipment Supervisor Samuel Herrick, Ph.D Mathemat ician Lillian Sloane General Clerk Magnus R. Hestenes, Ph.D Mathemat ician Irene A. Stegun, M.A. Mathematician Mathemat ician Mark Kac , Ph.D Milton Stein Mathematician Cornelius Lanczos, Ph.D Mathematician Ruth Zucker, B.A Mathematician Alexander M. Ostrowski, Ph.D Mathematician Computers Raymond P. Peterson, Jr., M.A Mathematician John A. -

When Computers Were Human

When Computers Were Human When Computers Were Human David Alan Grier princeton university press princeton and oxford Copyright © 2005 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY All Rights Reserved Third printing, and first paperback printing, 2007 Paperback ISBN: 978-0-691-13382-9 The Library of Congress has cataloged the cloth edition of this book as follows Grier, David Alan, 1955 Feb. 14– When computers were human / David Alan Grier. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-691-09157-9 (acid-free paper) 1. Calculus—History. 2. Science—Mathematics—History. I. Title. QA303.2.G75 2005 510.922—dc22 2004022631 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Sabon Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ press.princeton.edu Printed in the United States of America 109876543 FOR JEAN Who took my people to be her people and my stories to be her own without realizing that she would have to accept a comet, the WPA, and the oft-told tale of a forgotten grandmother Contents Introduction A Grandmother’s Secret Life 1 Part I: Astronomy and the Division of Labor 9 1682–1880 Chapter One The First Anticipated Return: Halley’s Comet 1758 11 Chapter Two The Children of Adam Smith 26 Chapter Three The Celestial Factory: Halley’s Comet 1835 46 Chapter Four The American Prime Meridian 55 Chapter Five A Carpet for the Computing Room 72 Part II: -

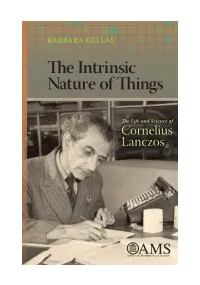

The Intrinsic Nature of Things the Life and Science of Cornelius Lanczos

BARBARA GELLAI Th e Intrinsic Nature of Th ings Th e Life and Science of Cornelius Lanczos The Intrinsic Nature of Things The Life and Science of Cornelius Lanczos http://dx.doi.org/10.1090/mbk/076 The Intrinsic Nature of Things The Life and Science of Cornelius Lanczos BARBARA GELLAI Providence, Rhode Island Cover photograph courtesy of the late Ida Rhodes: Cornelius Lanczos, visiting researcher at Boeing Aircraft Company, in 1944. 2010 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primary 01A60. For additional information and updates on this book, visit www.ams.org/bookpages/mbk-76 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gellai, Barbara, 1933– The intrinsic nature of things : the life and science of Cornelius Lanczos / Barbara Gellai. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8218-5166-1 (alk. paper) 1. Lanczos, Cornelius, 1893–1974. 2. Mathematicians—Hungary—Biography. 3. Physicists—Hungary—Biography. I. Title. QA29.L285G45 2010 510.92—dc22 [B] 2010017680 Copying and reprinting. Individual readers of this publication, and nonprofit libraries acting for them, are permitted to make fair use of the material, such as to copy a chapter for use in teaching or research. Permission is granted to quote brief passages from this publication in reviews, provided the customary acknowledgment of the source is given. Republication, systematic copying, or multiple reproduction of any material in this publication is permitted only under license from the American Mathematical Society. Requests for such permission should be addressed to the Acquisitions Department, American Mathematical Society, 201 Charles Street, Providence, Rhode Island 02904- 2294 USA. Requests can also be made by e-mail to [email protected]. -

Rm 229 Febbraio 2018

Rudi Mathematici Rivista fondata nell’altro millennio Numero 229 – Febbraio 2018 – Anno Ventesimo Rudi Mathematici Numero 228 – Febbraio 2018 1. Pietruzze e sassolini ....................................................................................................................... 3 2. Problemi ....................................................................................................................................... 13 2.1 Legge e Ordine! ......................................................................................................................... 13 2.2 Pianificazione a (si spera) lungo termine ................................................................................... 13 3. Bungee Jumpers .......................................................................................................................... 14 4. Soluzioni e Note ........................................................................................................................... 14 4.1 [226]........................................................................................................................................... 14 4.1.1 L’ultimo problema di quest’anno ........................................................................................ 14 4.2 [227]........................................................................................................................................... 17 4.2.1 L’emeroteca di Babele ........................................................................................................ -

Projects and Publications of the Applied Mathematics

Projects and Publications of the NATIONAL APPLIED MATHEMATICS LABORATORIES A QUARTERLY REPORT January through March 1950 NATIONAL APPLIED MATHEMATICS LABORATORIES of the NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS NATIONAL APPLIED MATHEMATICS LABORATORIES January 1 through March 31, 1950 ADMIN I SHUT I VE OFFICE John H. Curtiss, Ph.D., Chief Edward W, Camion, Ph.D., Assistant Chief Olga Taus sky -Todd, Ph.D., Mathematics Consultant Myrtle R. Kel ling ton, M- A., Technical Aid Luis 0. Rodriguez, M.A., Chief Clerk John B. Tallerico, B.C.S., Assistant Chief Clerk Jacqueline Y. Barch, Secretary Dora P. Cornwell, Secretary Esther McCraw, Secretary Pauline F. Peterson, Secretary INSTITUTE FOR NUMERICAL ANALYSIS COMPUTATION LABORATORY Los Angeles, California J. Barkley Rosser, ph. D Director of Research Jolm Todd, B. S- , Chief Albert S. Cahn, Jr., M.S. Assistant to Director Franz L. Alt, Ph.D Assistant Chief Arnold N. Lowan, Ph.D....... Consul t&nt Research Staff Milton Abramowitz, Ph.D Ma thematic ian Forman S. Acton, ph.D. Mathematician Donald 0. Larson, B.S Mathematician George E. Forsythe, Ph.D.-. Mathematician Joseph H. Levin, Ph.D Mathematician Magnus R. Hestenes, Ph.D Mathematician Robert R. Reynolds, M.S Mathematician William Karush, ph.D . Mathematician Herbert E. Salzer, M.A...... ...... ....... Mathematician Cornelius Lanczos, Ph.D , Mathematician Irene A. Stegun, M.A. ....... Mathematician Otto Szasz, Ph.D Mathematician Computing Staff: Wolfgang R, Wasow, Ph.D... Mathematician Oneida L. Baylor Henry B. Juenemann, B.A. Joseph Blum, M.A. Kenneth Levenberg, M.S. Graduate Fellows: Ruth E. Capuano Lionel Levinson, B. M.E. George E. Gourrich, B. S.