On the Permissibility of Homicidal Violence: Perspectives from Former U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: to Stop the Defamation of the Jewish People and to Secure Justice and Fair Treatment for All

A report from the Center on Extremism 09 18 New Hate and Old: The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: To stop the defamation of the Jewish people and to secure justice and fair treatment for all. ABOUT T H E CENTER ON EXTREMISM The ADL Center on Extremism (COE) is one of the world’s foremost authorities ADL (Anti-Defamation on extremism, terrorism, anti-Semitism and all forms of hate. For decades, League) fights anti-Semitism COE’s staff of seasoned investigators, analysts and researchers have tracked and promotes justice for all. extremist activity and hate in the U.S. and abroad – online and on the ground. The staff, which represent a combined total of substantially more than 100 Join ADL to give a voice to years of experience in this arena, routinely assist law enforcement with those without one and to extremist-related investigations, provide tech companies with critical data protect our civil rights. and expertise, and respond to wide-ranging media requests. Learn more: adl.org As ADL’s research and investigative arm, COE is a clearinghouse of real-time information about extremism and hate of all types. COE staff regularly serve as expert witnesses, provide congressional testimony and speak to national and international conference audiences about the threats posed by extremism and anti-Semitism. You can find the full complement of COE’s research and publications at ADL.org. Cover: White supremacists exchange insults with counter-protesters as they attempt to guard the entrance to Emancipation Park during the ‘Unite the Right’ rally August 12, 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia. -

Bill Analysis and Fiscal Impact Statement

The Florida Senate BILL ANALYSIS AND FISCAL IMPACT STATEMENT (This document is based on the provisions contained in the legislation as of the latest date listed below.) Prepared By: The Professional Staff of the Committee on Infrastructure and Security BILL: SR 222 INTRODUCER: Senator Simpson and others SUBJECT: White Nationalism and White Supremacy DATE: January 9, 2020 REVISED: ANALYST STAFF DIRECTOR REFERENCE ACTION 1. Proctor Miller IS Pre-meeting 2. JU 3. RC I. Summary: SR 222 rejects white nationalism and white supremacy as hateful, dangerous, and morally corrupt, and affirms that such philosophies are contradictory to the values that define the people of Florida. Legislative resolutions have no force of law and are not subject to the approval or veto powers of the Governor. II. Present Situation: White nationalist groups espouse white supremacist or white separatist ideologies.1 The term “white supremacist extremism” (WSE) describes people or groups who commit criminal acts in the name of white supremacist ideology. At its core, white supremacist ideology purports that the white race ranks above all others. WSE draws on the constitutionally protected activities of a broad swath of racist hate-oriented groups active in the United States ranging from the Ku Klux Klan to racist skinheads. Some of these groups have elaborate organizational structures, dues- paying memberships, and media wings. Additionally, many individuals espouse extremist beliefs without having formal membership in any specific organization.2 1 Southern Poverty Law Center, White Nationalist, https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/ideology/white- nationalist (last visited October 11, 2019). 2 Congressional Research Office, Domestic Terrorism: An Overview, Report R44921, August 21, 2017, Jerome P. -

A Case Study of the New Christian Crusade Church, 1971 – 1982

Christian Identity and Fascism: A Case Study of the New Christian Crusade Church, 1971 – 1982 Richard Lancaster 1 Contents List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................ 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 4 Chapter 1: A History of the New Christian Crusade Church ................................. 12 Chapter 2: The Ideology of the New Christian Crusade Church ........................... 25 Conclusion ............................................................................................................. 39 Bibliography ........................................................................................................... 42 2 List of Abbreviations ANP – American Nazi Party CDL – Christian Defense League NCCC – New Christian Crusade Church NSRP – National States’ Rights Party NSWPP – National Socialist White People’s Party 3 Introduction The New Christian Crusade Church (NCCC) was a California and Louisiana based ‘Christian Identity’ organisation formed by James K. Warner in 1971. Christian Identity theology holds the Aryan race as the racial descendants of the biblical Israelites, and therefore God’s chosen people.1 It was an off spring of Anglo-Israelism, a 19th Century British movement which held a similar myth concerning the biblical origins of the white race. Anglo-Israelism began to enter America in the mid to late 19th century, and from the 1930s, the movement took -

WITH HATE in THEIR HEARTS the State of White Supremacy in the United States

WITH HATE IN THEIR HEARTS The State of White Supremacy in the United States July 2015 ANTI-DEFAMATION LEAGUE Barry Curtiss-Lusher National Chair Jonathan A. Greenblatt National Director Kenneth Jacobson Deputy National Director Milton S. Schneider President, Anti-Defamation League Foundation CIVIL RIGHTS DIVISION Christopher Wolf Chair Deborah M. Lauter Director Steven M. Freeman Associate Director Eva Vega-Olds Assistant Director CENTER ON EXTREMISM Mark Pitcavage* Director, Investigative Research Co-Director, Center on Extremism Marilyn Mayo Oren Segal Co-Directors *Report Author For additional and updated resources please see: www.adl.org Copies of this publication are available in the Rita and Leo Greenland Library and Research Center. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The recent tragic shooting spree in June 2015 that took nine lives at Emanuel AME Church, a predominantly African- American church in Charleston, South Carolina, starkly revealed the pain and suffering that someone motivated by hate can cause. The suspect in the shootings, Dylann Storm Roof, is a suspected white supremacist. The horrific incident—following earlier deadly shooting sprees by white supremacists in Kansas, Wisconsin, and elsewhere— makes understanding white supremacy in the United States a necessity. • White supremacist ideology in the United States today is dominated by the belief that whites are doomed to extinction by a rising tide of non-whites who are controlled and manipulated by the Jews—unless action is taken now. This core belief is exemplified by slogans such as the so-called Fourteen Words: “We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children.” • During the recent surge of right-wing extremist activity in the United States that began in 2009, white supremacists did not grow appreciably in numbers, as anti-government extremists did, but existing white supremacists did become more angry and agitated, with a consequent rise of serious white supremacist violence. -

Fourteen Words

Fourteen Words Fourteen Words, or simply 14, is a reference to a white supremacist and white nationalist slogan: “We must se- cure the existence of our people and a future for white children.”[1][2][3] It can be used to refer to a different 14- word slogan: “Because the beauty of the White Aryan woman must not perish from the earth.”[4] 1 Origin Both slogans were coined by David Lane,[5] a member of the white supremacist group The Order, and publicized through the efforts of the now defunct Fourteen Word Press which helped popularize it and other writings of Lane.[6] The first slogan is claimed to have been inspired (albeit not by Lane or by Fourteen Word Press) by a state- Curtis Allgier's numerous tattoos include references to “14” and ment, 88 words in length, from Volume 1, Chapter 8 of “88” above and to the sides of “SKIN” and “HEAD”, above his Adolf Hitler's Mein Kampf: eyes.[7] What we must fight for is to safeguard the mugshot (right).[7] The numbers also figured prominently existence and reproduction of our race and our in the Barack Obama assassination plot in Tennessee,[12] people, the sustenance of our children and the which was intended to kill 88 African-Americans, includ- purity of our blood, the freedom and indepen- ing President Obama, 14 of whom were to be beheaded. dence of the fatherland, so that our people may mature for the fulfillment of the mission allot- ted it by the creator of the universe. Every thought and every idea, every doctrine and all 3 See also knowledge, must serve this purpose. -

Submission by the Human Rights Council of Australia Inc. to The

Submission by the Human Rights Council of Australia Inc. to the Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee Inquiry into Nationhood, National Identity and Democracy Abstract This submission argues that it is critical for community cohesion and in respect of observance of international human rights to recognise and address the racist elements present in the movements described as “populist, conservative nationalist and nativist” which the inquiry addresses. These elements include the promotion of concepts of "white nationalism" which are largely imported from North America and Europe. Racist movements adopt sophisticated recruitment and radicalisation techniques similar to those seen among jihadists. Hate speech requires a strengthened national response and we recommend that its most extreme forms be criminalised in federal law, taking into account relevant human rights principles. A comprehensive annual report is required to ensure that key decision makers including parliamentarians are well-informed about the characteristics and methods of extremist actors. Further, noting the openly racist call for a return of the “White Australia” policy by a former parliamentarian, a Parliamentary Code of Ethics, which previous inquiries have recommended, is now essential. The immigration discourse is particularly burdened with implicit (and sometimes explicit) racist messaging. It is essential that an evidence base be developed to remove racist effects from immigration and other national debates. International human rights are a purpose-designed response to racism and racist nationalism. They embody the learned experience of the postwar generation. Human rights need to be drawn on more systematically to promote community cohesion and counter hate. Community cohesion and many Australians would be significantly harmed by any return to concepts of an ethnically or racially defined “nation”. -

Communication from Evan Balgord

EA2.1.4 To the Members of the Compliance Audit Committee, Thank you for hearing our application for an audit of the campaign finances of Faith Goldy. I am a personal applicant in this matter, but do so in connection with my role as Executive Director of the Canadian Anti-Hate Network. I regret that I have a prior commitment that requires me to be out of the province on April 29th and unable to address the committee in person. In my stead, my colleague, Bernie Farber will be in attendance, along with recently retained legal counsel, Jack Siegel, of Blaney McMurtry LLP. Ms. Goldy’s intention to violate the fundraising provisions contained in the Municipal Elections Act, 1996 is apparent from her own words, contained in an online video solicitation that she herself has published, where she may be heard to clearly say, “I’m accepting donations from defenders of democracy WORLDWIDE.” See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ip1qIfFgeOU In another video she has further acknowledged that “We gathered over $50,000 through my political campaign in order to have this case heard,” thereby confirming that campaign finances were used to pay for her failed lawsuit. See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qXVnznVa88A&t=541s (at 9:15 of video) Under S. 88.8 (3): “Who may contribute (3) Only the following persons may make contributions: 1. An individual who is normally resident in Ontario.” Under S. 88.9 (1): “Maximum contributions to candidates 88.9 (1) A contributor shall not make contributions exceeding a total of $1,200 to any one candidate in an election. -

Comparing White Supremacist Skinheads and the Alt-Right in New Zealand

Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online ISSN: (Print) 1177-083X (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tnzk20 Shaved heads and sonnenrads: comparing white supremacist skinheads and the alt-right in New Zealand Jarrod Gilbert & Ben Elley To cite this article: Jarrod Gilbert & Ben Elley (2020): Shaved heads and sonnenrads: comparing white supremacist skinheads and the alt-right in New Zealand, Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online, DOI: 10.1080/1177083X.2020.1730415 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/1177083X.2020.1730415 © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 11 Mar 2020. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tnzk20 KOTUITUI: NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES ONLINE https://doi.org/10.1080/1177083X.2020.1730415 RESEARCH ARTICLE Shaved heads and sonnenrads: comparing white supremacist skinheads and the alt-right in New Zealand Jarrod Gilberta and Ben Elleyb aCriminal Justice, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand; bSociology, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Thisarticlelooksattwoperiodsinthe history of white supremacy in New Received 14 October 2019 Zealand: the short-lived explosion of skinhead groups in the 1990s, and Accepted 7 February 2020 the contemporary rise of the internet-driven alt-right. It looks at the KEYWORDS similarities and differences between the two groups, looking at style, Gangs; white supremacy; symbols, ideology, and behaviour. It looks at the history of these two skinheads; alt-right; New movements in New Zealand and compares the economic and social Zealand factors that contributed to their rise, in particular how the different social class of members produced groups with near-identical ideology but radically different presentation and modes of action. -

Courage Against Hate W

w JULY 2021 Courage Against Hate w Introduction The Courage Against Hate initiative has Hate and extremism have no place on Facebook and we have been brought together by Facebook for been making major investments over a number of years to improve detection of this content on our platforms, so we the purpose of sparking cross-sector, can remove it quicker - ideally before people see it and pan-European dialogue and action to report it to us. We’ve tripled - to more than 35,000 - the combat hate speech and extremism. people working on safety and security at Facebook, and This collection of articles unites European grown the dedicated team we have leading our efforts against terrorism and extremism to over 350 people. academic analysis with practitioners who This group includes former academics who are experts on are actively working on countering counterterrorism, former prosecutors and law enforcement extremism within civil society. agents, investigators and analysts, and engineers. We’ve also developed and iterated various technologies to make us faster and better at identifying this type of material automatically. This includes photo and video matching tools and text-based machine-learning classifiers. Last year, as a result of these investments, we removed more than 19 million pieces of content related to hate organisations last year, over 97% of which we proactively identified and removed before anyone reported it to us. While we are making good progress, we know that working to keep hateful and extremist content off Facebook is not enough, because this content proliferates across the web and wider society, often in different ways. -

1 U.S. White Supremacy Groups Key Points: • Some Modern White

U.S. White Supremacy Groups Key Points: • Some modern white supremacist groups, such as The Base, Hammerskin Nation, and National Socialist Order (formerly Atomwaffen Division), subscribe to a National Socialist (neo-Nazi) ideology. These groups generally make no effort to hide their overt racist belief that the white race is superior to others. • Other modern white supremacist groups, however, propagate their radical stances under the guise of white ethno-nationalism, which seeks to highlight the distinctiveness––rather than the superiority––of the white identity. Such groups, which include the League of the South and Identity Evropa, usually claim that white identity is under threat from minorities or immigrants that seek to replace its culture, and seek to promote white ethno- nationalism as a legitimate ideology that belongs in mainstream political spheres. • Most modern white supremacist groups eschew violent tactics in favor of using demonstrations and propaganda to sway public opinion and portray their ideologies as legitimate. However, their racial elitist ideologies have nonetheless spurred affiliated individuals to become involved in violent altercations. • White supremacist groups often target youth for recruitment through propaganda campaigns on university campuses and social media platforms. White supremacists have long utilized Internet forums and websites to connect, organize, and propagate their extremist messages. Executive Summary Since the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) first formed in 1865, white supremacist groups in the United States have propagated racism, hatred, and violence. Individuals belonging to these groups have been charged with a range of crimes, including civil rights violations, racketeering, solicitation to commit crimes of violence, firearms and explosives violations, and witness tampering.1 Nonetheless, white supremacist groups––and their extremist ideologies––persist in the United States today. -

How to Save Western Civilization (For Men): White Supremacy and the New Kyrieia

How to Save Western Civilization (for Men): White Supremacy and the New Kyrieia In late 2015, Daryush “Roosh V” Valizadeh – a pickup artist-turned-reactionary theorist of masculinity – published a blog post on his personal website with the title “Women Must Have Their Behavior and Decisions Controlled By Men.” In that post he argues that, because men are more rational and less emotional than women, men necessarily have better decision-making skills. He writes, “I propose two different options for protecting women from their obviously deficient decision making. The first is to have a designated male guardian give approval on all decisions that affect her well-being. Such a guardian should be her father by default, but in the case a father is absent, another male relative can be appointed… Once the woman is married, her husband will gradually take over guardian duties, and strictly monitor his wife’s behavior…” He concludes, “Unless we take action soon to reconsider the freedoms that women now have, the very survival of Western civilization is at stake.” Valizadeh justifies his solution historically: “For the bulk of human history, their behavior was significantly controlled or subject to approval through mechanisms of tribe, family, church, law, or stiff cultural precepts.” As he suggests, his idea is a very old one, with striking similarities to the Athenian custom of kyrieia and Roman tutela. Although controversial for its time, in the two and a half years since its publication this argument has gained widespread acceptance in far-right internet circles, particularly in the so- called “alt-right” and “manosphere.” Many writers for these sites argue that the health of our civilization depends upon enacting a sexual politics that they call either “White Sharia” or simply “patriarchy,” but which closely resembles the sexual politics and marriage laws of classical Athens and Rome under the late Republic and early Empire. -

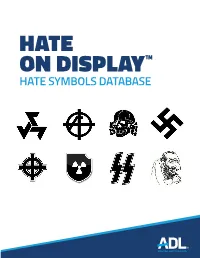

Hate Symbols Database

HATE ON DISPLAY™ HATE SYMBOLS DATABASE 1 HATE ON DISPLAY This database provides an overview of many of the symbols most frequently used by a variety of white supremacist groups and movements, as well as some other types of hate groups. You can find the full listings at adl.org/hate-symbols INTRODUCTION TO THE HATE ON DISPLAY HATE SYMBOLS DATABASE ADL is a leading anti-hate organization that was founded in 1913 in response to an escalating climate of anti-Semitism and bigotry. Today, ADL is the first call when acts of anti-Semitism occur and continues to fight all forms of hate. A global leader in exposing extremism, delivering anti-bias education and fighting hate online, ADL’s ultimate goal is a world in which no group or individual suffers from bias, discrimination or hate. ADL’s Center on Extremism debuted its Hate on Display hate symbols database in 2000, establishing the database as the first and foremost resource on the internet for symbols, codes, and memes used by white supremacists and other types of haters. Over the past two decades, Hate on Display has regularly been updated with new symbols and images as they have come into common use by extremists, as well as new functions to make it more useful and convenient for users. Although the database contains many examples of online usage and shared graphics, another feature that makes it unique is its emphasis on real world examples of hate symbols—showing them as extremists actually use them: on signs and clothing, graffiti and jewelry, and even on their own bodies as tattoos and brands.