The Role of White Nationalism in Us

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

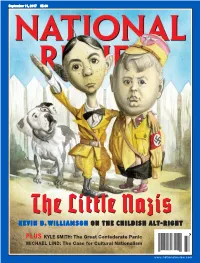

The Little Nazis KE V I N D

20170828 subscribers_cover61404-postal.qxd 8/22/2017 3:17 PM Page 1 September 11, 2017 $5.99 TheThe Little Nazis KE V I N D . W I L L I A M S O N O N T H E C HI L D I S H A L T- R I G H T $5.99 37 PLUS KYLE SMITH: The Great Confederate Panic MICHAEL LIND: The Case for Cultural Nationalism 0 73361 08155 1 www.nationalreview.com base_new_milliken-mar 22.qxd 1/3/2017 5:38 PM Page 1 !!!!!!!! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! "e Reagan Ranch Center ! 217 State Street National Headquarters ! 11480 Commerce Park Drive, Santa Barbara, California 93101 ! 888-USA-1776 Sixth Floor ! Reston, Virginia 20191 ! 800-USA-1776 TOC-FINAL_QXP-1127940144.qxp 8/23/2017 2:41 PM Page 1 Contents SEPTEMBER 11, 2017 | VOLUME LXIX, NO. 17 | www.nationalreview.com ON THE COVER Page 22 Lucy Caldwell on Jeff Flake The ‘N’ Word p. 15 Everybody is ten feet tall on the BOOKS, ARTS Internet, and that is why the & MANNERS Internet is where the alt-right really lives, one big online 35 THE DEATH OF FREUD E. Fuller Torrey reviews Freud: group-therapy session The Making of an Illusion, masquerading as a political by Frederick Crews. movement. Kevin D. Williamson 37 ILLUMINATIONS Michael Brendan Dougherty reviews Why Buddhism Is True: The COVER: ROMAN GENN Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment, ARTICLES by Robert Wright. DIVIDED THEY STAND (OR FALL) by Ramesh Ponnuru 38 UNJUST PROSECUTION 12 David Bahnsen reviews The Anti-Trump Republicans are not facing their challenges. -

The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: to Stop the Defamation of the Jewish People and to Secure Justice and Fair Treatment for All

A report from the Center on Extremism 09 18 New Hate and Old: The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: To stop the defamation of the Jewish people and to secure justice and fair treatment for all. ABOUT T H E CENTER ON EXTREMISM The ADL Center on Extremism (COE) is one of the world’s foremost authorities ADL (Anti-Defamation on extremism, terrorism, anti-Semitism and all forms of hate. For decades, League) fights anti-Semitism COE’s staff of seasoned investigators, analysts and researchers have tracked and promotes justice for all. extremist activity and hate in the U.S. and abroad – online and on the ground. The staff, which represent a combined total of substantially more than 100 Join ADL to give a voice to years of experience in this arena, routinely assist law enforcement with those without one and to extremist-related investigations, provide tech companies with critical data protect our civil rights. and expertise, and respond to wide-ranging media requests. Learn more: adl.org As ADL’s research and investigative arm, COE is a clearinghouse of real-time information about extremism and hate of all types. COE staff regularly serve as expert witnesses, provide congressional testimony and speak to national and international conference audiences about the threats posed by extremism and anti-Semitism. You can find the full complement of COE’s research and publications at ADL.org. Cover: White supremacists exchange insults with counter-protesters as they attempt to guard the entrance to Emancipation Park during the ‘Unite the Right’ rally August 12, 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia. -

Varieties of Familialism: Comparing Four Southern European and East Asian Welfare Regimes

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Saraceno, Chiara Article — Published Version Varieties of familialism: Comparing four southern European and East Asian welfare regimes Journal of european social policy Provided in Cooperation with: WZB Berlin Social Science Center Suggested Citation: Saraceno, Chiara (2016) : Varieties of familialism: Comparing four southern European and East Asian welfare regimes, Journal of european social policy, ISSN 1461-7269, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, Vol. 26, Iss. 4, pp. 314–326, http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0958928716657275 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/171966 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu ESP0010.1177/0958928716657275Journal of European Social PolicySaraceno 657275research-article2016 Journal Of European Article Social Policy Journal of European Social Policy 2016, Vol. -

Value All Care, Value Every Family

Value All Care, Value Every Family familyvaluesatwork.org Value All Care, Value Every Family More and more people of all political persuasions acknowledge that paid leave is an issue whose time has come. As we enter the “not if but when” stage of creating public policy, we need to make sure the program values all care and values every family. Parents urgently need paid time to welcome a new child into their homes. But more than three-quarters of those who take unpaid leave under the Family and Medical Leave Act do so to care for a loved one or for their own serious illness. Our paid leave program cannot leave them out. The stories in this booklet come from people across the country. Each of them faced an unexpected injury or illness, like most of us do at some point. And like us, they just want to take care of themselves and their loved ones without falling off an economic cliff. It would be very difficult to cure or prevent all the ailments described in this booklet. But it should not be difficult to reach bipartisan agreement on a paid leave plan that is accessible for all kinds of care and affordable to every family. familyvaluesatwork.org • The Impact of Our Wins Caring For Yourself familyvaluesatwork.org • Value All Care, Value Every Family Caring For Yourself Janet Valencia, Tucson, Arizona everal years ago when I was a single mom I worked as a registered nurse in Tucson, often through an agency with no paid leave. I did this so that I could arrange to work and also take care of my children. -

Was Ann Coulter Right? Some Realism About “Minimalism”

AMLR.V5I1.PRESSER.POSTPROOFLAYOUT.0511 9/16/2008 3:21:27 PM Copyright © 2007 Ave Maria Law Review WAS ANN COULTER RIGHT? SOME REALISM ABOUT “MINIMALISM” Stephen B. Presser † INTRODUCTION Ever since the Warren Court rewrote much of the Bill of Rights and the Fourteenth Amendment, there has been a debate within legal academia about the legitimacy of this judicial law making.1 Very little popular attention was paid, at least in the last several decades, to this problem. More recently, however, the issue of the legitimacy of judicial law making has begun to enter the realm of partisan popular debate. This is due to the fact that Republicans controlled the White House for six years and a majority in the Senate for almost all of that time, that they have announced, as it were, a program of picking judges committed to adjudication rather than legislation, and finally, that the Democrats have, just as vigorously, resisted Republican efforts. Cass Sunstein, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School,2 and now a visiting professor at Harvard Law School,3 has written a provocative book purporting to be a popular, yet scholarly critique of the sort of judges President George W. Bush has announced that he would like to appoint. Is Sunstein’s effort an objective undertaking, or is it partisan politics with a thin academic veneer? If Sunstein’s work (and that of others on the Left in the † Raoul Berger Professor of Legal History, Northwestern University School of Law; Professor of Business Law, J. L. Kellogg Graduate School of Management, Northwestern University; Legal Affairs Editor, Chronicles: A Magazine of American Culture. -

Christian America in Black and White: Racial Identity, Religious-National Group Boundaries, and Explanations for Racial Inequality

1 Forthcoming in Sociology of Religion Christian America in Black and White: Racial Identity, Religious-National Group Boundaries, and Explanations for Racial Inequality Samuel L. Perry University of Oklahoma Andrew L. Whitehead Clemson University Abstract Recent research suggests that, for white Americans, conflating national and religious group identities is strongly associated with racism, xenophobia, and Islamophobia, prompting some to argue that claims about Christianity being central to American identity are essentially about reinforcing white supremacy. Prior work has not considered, however, whether such beliefs may influence the racial views of non-white Americans differently from white Americans. Drawing on a representative sample of black and white Americans from the 2014 General Social Survey, and focusing on explanations for racial inequality as the outcome, we show that, contrary to white Americans, black Americans who view being a Christian as essential to being an American are actually more likely to attribute black-white inequality to structural issues and less to blacks’ individual shortcomings. Our findings suggest that, for black Americans, connecting being American to being Christian does not necessarily bolster white supremacy, but may instead evoke and sustain ideals of racial justice. Keywords: Christian America, racism, racial inequality, black Americans, religion 2 A centerpiece of Donald Trump’s presidency―a presidency now famous for heightened racial strife and the emboldening of white supremacists―is a commitment to defend America’s supposed “Christian heritage.” Trump announced to his audience at Oral Roberts University during his campaign “There is an assault on Christianity…There is an assault on everything we stand for, and we’re going to stop the assault” (Justice and Berglund 2016). -

The Radical Roots of the Alt-Right

Gale Primary Sources Start at the source. The Radical Roots of the Alt-Right Josh Vandiver Ball State University Various source media, Political Extremism and Radicalism in the Twentieth Century EMPOWER™ RESEARCH The radical political movement known as the Alt-Right Revolution, and Evolian Traditionalism – for an is, without question, a twenty-first century American audience. phenomenon.1 As the hipster-esque ‘alt’ prefix 3. A refined and intensified gender politics, a suggests, the movement aspires to offer a youthful form of ‘ultra-masculinism.’ alternative to conservatism or the Establishment Right, a clean break and a fresh start for the new century and .2 the Millennial and ‘Z’ generations While the first has long been a feature of American political life (albeit a highly marginal one), and the second has been paralleled elsewhere on the Unlike earlier radical right movements, the Alt-Right transnational right, together the three make for an operates natively within the political medium of late unusual fusion. modernity – cyberspace – because it emerged within that medium and has been continuously shaped by its ongoing development. This operational innovation will Seminal Alt-Right figures, such as Andrew Anglin,4 continue to have far-reaching and unpredictable Richard Spencer,5 and Greg Johnson,6 have been active effects, but researchers should take care to precisely for less than a decade. While none has continuously delineate the Alt-Right’s broader uniqueness. designated the movement as ‘Alt-Right’ (including Investigating the Alt-Right’s incipient ideology – the Spencer, who coined the term), each has consistently ferment of political discourses, images, and ideas with returned to it as demarcating the ideological territory which it seeks to define itself – one finds numerous they share. -

Post-Truth Politics and Richard Rorty's Postmodernist Bourgeois Liberalism

Ash Center Occasional Papers Tony Saich, Series Editor Something Has Cracked: Post-Truth Politics and Richard Rorty’s Postmodernist Bourgeois Liberalism Joshua Forstenzer University of Sheffield (UK) July 2018 Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation Harvard Kennedy School Ash Center Occasional Papers Series Series Editor Tony Saich Deputy Editor Jessica Engelman The Roy and Lila Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation advances excellence and innovation in governance and public policy through research, education, and public discussion. By training the very best leaders, developing powerful new ideas, and disseminating innovative solutions and institutional reforms, the Center’s goal is to meet the profound challenges facing the world’s citizens. The Ford Foundation is a founding donor of the Center. Additional information about the Ash Center is available at ash.harvard.edu. This research paper is one in a series funded by the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. The views expressed in the Ash Center Occasional Papers Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or of Harvard University. The papers in this series are intended to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important public policy challenges. This paper is copyrighted by the author(s). It cannot be reproduced or reused without permission. Ash Center Occasional Papers Tony Saich, Series Editor Something Has Cracked: Post-Truth Politics and Richard Rorty’s Postmodernist Bourgeois Liberalism Joshua Forstenzer University of Sheffield (UK) July 2018 Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation Harvard Kennedy School Letter from the Editor The Roy and Lila Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation advances excellence and innovation in governance and public policy through research, education, and public discussion. -

Introduction

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction The Invention of an Ethnic Nationalism he Hindu nationalist movement started to monopolize the front pages of Indian newspapers in the 1990s when the political T party that represented it in the political arena, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP—which translates roughly as Indian People’s Party), rose to power. From 2 seats in the Lok Sabha, the lower house of the Indian parliament, the BJP increased its tally to 88 in 1989, 120 in 1991, 161 in 1996—at which time it became the largest party in that assembly—and to 178 in 1998. At that point it was in a position to form a coalition government, an achievement it repeated after the 1999 mid-term elections. For the first time in Indian history, Hindu nationalism had managed to take over power. The BJP and its allies remained in office for five full years, until 2004. The general public discovered Hindu nationalism in operation over these years. But it had of course already been active in Indian politics and society for decades; in fact, this ism is one of the oldest ideological streams in India. It took concrete shape in the 1920s and even harks back to more nascent shapes in the nineteenth century. As a movement, too, Hindu nationalism is heir to a long tradition. Its main incarnation today, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS—or the National Volunteer Corps), was founded in 1925, soon after the first Indian communist party, and before the first Indian socialist party. -

The Alt-Right on Campus: What Students Need to Know

THE ALT-RIGHT ON CAMPUS: WHAT STUDENTS NEED TO KNOW About the Southern Poverty Law Center The Southern Poverty Law Center is dedicated to fighting hate and bigotry and to seeking justice for the most vulnerable members of our society. Using litigation, education, and other forms of advocacy, the SPLC works toward the day when the ideals of equal justice and equal oportunity will become a reality. • • • For more information about the southern poverty law center or to obtain additional copies of this guidebook, contact [email protected] or visit www.splconcampus.org @splcenter facebook/SPLCenter facebook/SPLConcampus © 2017 Southern Poverty Law Center THE ALT-RIGHT ON CAMPUS: WHAT STUDENTS NEED TO KNOW RICHARD SPENCER IS A LEADING ALT-RIGHT SPEAKER. The Alt-Right and Extremism on Campus ocratic ideals. They claim that “white identity” is under attack by multicultural forces using “politi- An old and familiar poison is being spread on col- cal correctness” and “social justice” to undermine lege campuses these days: the idea that America white people and “their” civilization. Character- should be a country for white people. ized by heavy use of social media and memes, they Under the banner of the Alternative Right – or eschew establishment conservatism and promote “alt-right” – extremist speakers are touring colleges the goal of a white ethnostate, or homeland. and universities across the country to recruit stu- As student activists, you can counter this movement. dents to their brand of bigotry, often igniting pro- In this brochure, the Southern Poverty Law Cen- tests and making national headlines. Their appear- ances have inspired a fierce debate over free speech ter examines the alt-right, profiles its key figures and the direction of the country. -

Domestic Ethnic Nationalism and Regional European Transnationalism: a Confluence of Impediments Opposing Turkey’S EU Accession Bid Glen M.E

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville History and Government Faculty Presentations Department of History and Government 4-3-2013 Domestic Ethnic Nationalism and Regional European Transnationalism: A Confluence of Impediments Opposing Turkey’s EU Accession Bid Glen M.E. Duerr Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ history_and_government_presentations Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Duerr, Glen M.E., "Domestic Ethnic Nationalism and Regional European Transnationalism: A Confluence of Impediments Opposing Turkey’s EU Accession Bid" (2013). History and Government Faculty Presentations. 26. https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/history_and_government_presentations/26 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in History and Government Faculty Presentations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Domestic Ethnic Nationalism and Regional European Transnationalism: A Confluence of Impediments Opposing Turkey’s EU Accession Bid Glen M.E. Duerr Assistant Professor of International Studies Cedarville University [email protected] Paper prepared for the International Studies Association (ISA) conference in San Francisco, California, April 2-5, 2013 This paper constitutes a preliminary -

Preliminary Program Book

PRELIMINARY PROGRAM BOOK Friday - 8:00 AM-12:00 PM A20-100 Status of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex, and Queer Persons in the Profession Committee Meeting Patrick S. Cheng, Chicago Theological Seminary, Presiding Friday - 8:00 AM-12:00 PM Friday - 8:00 AM-1:00 PM A20-101 Status of Women in the Profession Committee Meeting Su Yon Pak, Union Theological Seminary, Presiding Friday - 8:00 AM-1:00 PM Friday - 9:00 AM-12:00 PM A20-102 Public Understanding of Religion Committee Meeting Michael Kessler, Georgetown University, Presiding Friday - 9:00 AM-12:00 PM Friday - 9:00 AM-1:00 PM A20-103 Status of Racial and Ethnic Minorities in the Profession Committee Meeting Nargis Virani, New York, NY, Presiding Friday - 9:00 AM-1:00 PM Friday - 9:00 AM-2:00 PM A20-104 International Connections Committee Meeting Amy L. Allocco, Elon University, Presiding Friday - 9:00 AM-2:00 PM Friday - 9:00 AM-5:00 PM A20-105 Regional Coordinators Meeting Susan E. Hill, University of Northern Iowa, Presiding Friday - 9:00 AM-5:00 PM A20-106 THATCamp - The Humanities and Technology Camp Eric Smith, Iliff School of Theology, Presiding John Crow, Florida State University, Presiding Michael Hemenway, Iliff School of Theology/University of Denver, Presiding Theme: THATCampAARSBL2015 Friday - 9:00 AM-5:00 PM Friday - 10:00 AM-1:00 PM A20-107 American Lectures in the History of Religions Committee Meeting Louis A. Ruprecht, Georgia State University, Presiding Friday - 10:00 AM-1:00 PM Friday - 11:00 AM-6:00 PM A20-108 Religion and Media Workshop Ann M.