Chapter 1 – Introduction and Research Methodology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vigilantism V. the State: a Case Study of the Rise and Fall of Pagad, 1996–2000

Vigilantism v. the State: A case study of the rise and fall of Pagad, 1996–2000 Keith Gottschalk ISS Paper 99 • February 2005 Price: R10.00 INTRODUCTION South African Local and Long-Distance Taxi Associa- Non-governmental armed organisations tion (SALDTA) and the Letlhabile Taxi Organisation admitted that they are among the rivals who hire hit To contextualise Pagad, it is essential to reflect on the squads to kill commuters and their competitors’ taxi scale of other quasi-military clashes between armed bosses on such a scale that they need to negotiate groups and examine other contemporary vigilante amnesty for their hit squads before they can renounce organisations in South Africa. These phenomena such illegal activities.6 peaked during the1990s as the authority of white su- 7 premacy collapsed, while state transfor- Petrol-bombing minibuses and shooting 8 mation and the construction of new drivers were routine. In Cape Town, kill- democratic authorities and institutions Quasi-military ings started in 1993 when seven drivers 9 took a good decade to be consolidated. were shot. There, the rival taxi associa- clashes tions (Cape Amalgamated Taxi Associa- The first category of such armed group- between tion, Cata, and the Cape Organisation of ings is feuding between clans (‘faction Democratic Taxi Associations, Codeta), fighting’ in settler jargon). This results in armed groups both appointed a ‘top ten’ to negotiate escalating death tolls once the rural com- peaked in the with the bus company, and a ‘bottom ten’ batants illegally buy firearms. For de- as a hit squad. The police were able to cades, feuding in Msinga1 has resulted in 1990s as the secure triple life sentences plus 70 years thousands of displaced persons. -

Joseph Stalin Revolutionary, Politician, Generalissimus and Dictator

Military Despatches Vol 34 April 2020 Flip-flop Generals that switch sides Surviving the Arctic convoys 93 year WWII veteran tells his story Joseph Stalin Revolutionary, politician, Generalissimus and dictator Aarthus Air Raid RAF Mosquitos destory Gestapo headquarters For the military enthusiast CONTENTS April 2020 Page 14 Click on any video below to view How much do you know about movie theme songs? Take our quiz and find out. Hipe’s Wouter de The old South African Goede interviews former Defence Force used 28’s gang boss David a mixture of English, Williams. Afrikaans, slang and techno-speak that few Russian Special Forces outside the military could hope to under- stand. Some of the terms Features 34 were humorous, some A matter of survival were clever, while others 6 This month we continue with were downright crude. Ten generals that switched sides our look at fish and fishing for Imagine you’re a soldier heading survival. into battle under the leadership of Part of Hipe’s “On the a general who, until very recently 30 couch” series, this is an been trying very hard to kill you. interview with one of How much faith and trust would Ranks you have in a leader like that? This month we look at the author Herman Charles Army of the Republic of Viet- Bosman’s most famous 20 nam (ARVN), the South Viet- characters, Oom Schalk Social media - Soldier’s menace namese army. A taxi driver was shot Lourens. Hipe spent time in These days nearly everyone has dead in an ongoing Hanover Park, an area a smart phone, laptop or PC plagued with gang with access to the Internet and Quiz war between rival taxi to social media. -

A Short Chronicle of Warfare in South Africa Compiled by the Military Information Bureau*

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 16, Nr 3, 1986. http://scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za A short chronicle of warfare in South Africa Compiled by the Military Information Bureau* Khoisan Wars tween whites, Khoikhoi and slaves on the one side and the nomadic San hunters on the other Khoisan is the collective name for the South Afri- which was to last for almost 200 years. In gen- can people known as Hottentots and Bushmen. eral actions consisted of raids on cattle by the It is compounded from the first part of Khoi San and of punitive commandos which aimed at Khoin (men of men) as the Hottentots called nothing short of the extermination of the San themselves, and San, the names given by the themselves. On both sides the fighting was ruth- Hottentots to the Bushmen. The Hottentots and less and extremely destructive of both life and Bushmen were the first natives Dutch colonist property. encountered in South Africa. Both had a relative low cultural development and may therefore be During 18th century the threat increased to such grouped. The Colonists fought two wars against an extent that the Government had to reissue the the Hottentots while the struggle against the defence-system. Commandos were sent out and Bushmen was manned by casual ranks on the eventually the Bushmen threat was overcome. colonist farms. The Frontier War (1779-1878) The KhoiKhoi Wars This term is used to cover the nine so-called "Kaffir Wars" which took place on the eastern 1st Khoikhoi War (1659-1660) border of the Cape between the Cape govern- This was the first violent reaction of the Khoikhoi ment and the Xhosa. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

Creating Provinces for a New South Africa, 1993

NEGOTIATING DIVISIONS IN A DIVIDED LAND: CREATING PROVINCES FOR A NEW SOUTH AFRICA, 1993 SYNOPSIS As South Africa worked to draft a post-apartheid constitution in the months leading up to its first fully democratic elections in 1994, the disparate groups negotiating the transition from apartheid needed to set the country’s internal boundaries. By 1993, the negotiators had agreed that the new constitution would divide the country into provinces, but the thorniest issues remained: the number of provinces and their borders. Lacking reliable population data and facing extreme time pressure, the decision makers confronted explosive political challenges. South Africa in the early 1990s was a patchwork of provinces and “homelands,” ethnically defined areas for black South Africans. Some groups wanted provincial borders drawn according to ethnicity, which would strengthen their political bases but also reinforce divisions that had bedeviled the country’s political past. Those groups threatened violence if they did not get their way. To reconcile the conflicting interests and defuse the situation, the Multi-Party Negotiating Forum established a separate, multiparty commission. Both the commission and its technical committee comprised individuals from different party backgrounds who had relevant skills and expertise. They agreed on a set of criteria for the creation of new provinces and solicited broad input from the public. In the short term, the Commission on the Demarcation/Delimitation of States/Provinces/Regions balanced political concerns and technical concerns, satisfied most of the negotiating parties, and enabled the elections to move forward by securing political buy-in from a wide range of factions. In the long term, however, the success of the provincial boundaries as subnational administrations has been mixed. -

Class, Race and Gender Amongst White Volunteers, 1939-1953

From War to Workplace: Class, Race and Gender amongst White Volunteers, 1939-1953 By Neil Roos Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Faculty of Human and Social Sciences at the University of North West Supervisor: Dr. Tim Clynick Mafikeng, North West Province August 2001 To Dick Abstract Through a case study of the war and post-war experiences of those who volunteered to serve in the Second World War, the thesis explores aspects of the social and cultural history of white men in South Africa. The thesis begins from the premise that class and ethnicity, the major binary categories conventionally used to explain developments in white South African society, are unable to account for the history of white men who volunteered to serve in the Second World War. It argues that the history of these volunteers is best understood in the context of racist culture, which can be defined as an evolving consensus amongst whites in South Africa on the political, social and cultural primacy of whiteness. It argues that, when the call to arms came in 1939, it was answered mainly by white men from those little traditions incorporated politically into the segregationist colonial order, largely through the explicit emphases of white privilege and the cultural hegemony of whiteness. Their decision to enlist was underscored by an awareness that volunteering entailed a set of rights and duties, which centred on their expectations of post-war "social justice." Chapter three examines some of the highly idealised and implicitly racialised ways in which, during wartime, white troops expanded their understanding of social justice. -

Copyright © and Moral Rights for This Thesis Are Retained by the Author And/Or Other Copyright Owners

McDonald, Jared. (2015) Subjects of the Crown: Khoesan identity and assimilation in the Cape Colony, c. 1795- 1858. PhD thesis. SOAS University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/22831/ Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Subjects of the Crown: Khoesan Identity and Assimilation in the Cape Colony, c.1795-1858 Jared McDonald Department of History School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) University of London A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in History 2015 Declaration for PhD Thesis I declare that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the thesis which I present for examination. -

The Role and Application of the Union Defence Force in the Suppression of Internal Unrest, 1912 - 1945

THE ROLE AND APPLICATION OF THE UNION DEFENCE FORCE IN THE SUPPRESSION OF INTERNAL UNREST, 1912 - 1945 Andries Marius Fokkens Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Military Science (Military History) at the Military Academy, Saldanha, Faculty of Military Science, Stellenbosch University. Supervisor: Lieutenant Colonel (Prof.) G.E. Visser Co-supervisor: Dr. W.P. Visser Date of Submission: September 2006 ii Declaration I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously submitted it, in its entirety or in part, to any university for a degree. Signature:…………………….. Date:………………………….. iii ABSTRACT The use of military force to suppress internal unrest has been an integral part of South African history. The European colonisation of South Africa from 1652 was facilitated by the use of force. Boer commandos and British military regiments and volunteer units enforced the peace in outlying areas and fought against the indigenous population as did other colonial powers such as France in North Africa and Germany in German South West Africa, to name but a few. The period 1912 to 1945 is no exception, but with the difference that military force was used to suppress uprisings of white citizens as well. White industrial workers experienced this military suppression in 1907, 1913, 1914 and 1922 when they went on strike. Job insecurity and wages were the main causes of the strikes and militant actions from the strikers forced the government to use military force when the police failed to maintain law and order. -

Zelda Gordon & Associates

Zelda Gordon & Associates * j (Attorneys and Conveyancers) 574 Lansdowne Road Lansdowne 7780 P.O. Box 24351 *t? Lansdowne S Zintl 7780 OUR REF.:. Tel: (021) 761-8021/25 Telefax: (021) 761-8040 VOUR REF.: 18 Juna 1991 Attention: Nan Cross ECC National Office Telefax [Oil] 836 6931 Johannesburg > Dear Nan ECC POLICY ON CONSCRIPTION IN A POST APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA DRAFT DOCUMENT AS PREPARED BY CAPE TOWN END CONSCRIPTION CAMPAIGN We transmit a copy of the Policy Document as drafted by Katherine Mathers, Francois Krige and myself in response to the earlier draft and subsequent discussion at the National Conference and within the Cape Town Branch. ; We apologise for the slf'ght delay as occassioned by extreme pressure of work on ail concerned. Please do not hesitate to contact Katherine to discuss any aspects of the document. Yours in the Struggle ZELDA GORDON S. ASSOCIATES per i Steven ZINTI enc / as detailed totalling 3 pages herewith Zelda Gordon JUN-19-’91 UIED 10:10 ID:Z GORDON AND ASSOC TEL NO: 8332 P02 ECC POLICY ON CONSCRIPTION IN A POST APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA. PREAMBLE The End Conscription Campaign rejects racial conscription as it inevitably results in racial polarisation, mi 1itirisation and social damage. The ECC believes that in a post apartheid South Africa the coercion and force that has characterised our nation must be abolished. This means that conscription, both military i\ and non militaty, should not exist. The ECC believes that military conscription in a post apartheid SA should not b*e j'dtl of the defence force manpower procurment v policy, this is based on the belief that: / a. -

Apartheid's Hidden Hand -- the Power Behind "Black on Black Violence"

Apartheid's Hidden Hand -- The Power Behind "Black on Black Violence" http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.af000047 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Apartheid's Hidden Hand -- The Power Behind "Black on Black Violence" Alternative title Apartheid's Hidden Hand -- The Power Behind "Black on Black Violence" Author/Creator Fleshman, Mike Publisher Africa Fund Date 1990-10 Resource type Pamphlets Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1990 Source Africa Action Archive Rights By kind permission of Africa Action, incorporating the American Committee on Africa, The Africa Fund, and the Africa Policy Information Center. -

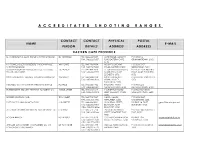

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714 -

Vietnam War Turning Back the Clock 93 Year Old Arctic Convoy Veteran Visits Russian Ship

Military Despatches Vol 33 March 2020 Myths and misconceptions Things we still get wrong about the Vietnam War Turning back the clock 93 year old Arctic Convoy veteran visits Russian ship Battle of Ia Drang First battle between the Americans and NVA For the military enthusiast CONTENTS March 2020 Click on any video below to view How much do you know about movie theme songs? Take our quiz and find out. Hipe’s Wouter de The old South African Page 14 Goede interviews former Defence Force used 28’s gang boss David a mixture of English, South Vietnamese Williams. Afrikaans, slang and techno-speak that few Special Forces outside the military could hope to under- stand. Some of the terms Features 32 were humorous, some Weapons and equipment were clever, while others 6 We look at some of the uniforms were downright crude. Ten myths about Vietnam and equipment used by the US Marine Corps in Vietnam dur- Although it ended almost 45 ing the 1960s years ago, there are still many Part of Hipe’s “On the myths and misconceptions 34 couch” series, this is an about the Vietnam War. We A matter of survival 26 interview with one of look at ten myths and miscon- This month we look at fish and author Herman Charles ceptions. ‘Mad Mike’ dies aged 100 fishing for survival. Bosman’s most famous 20 Michael “Mad Mike” Hoare, characters, Oom Schalk widely considered one of the 30 Turning back the clock Ranks Lourens. Hipe spent time in world’s best known mercenary, A taxi driver was shot When the Russian missile cruis- has died aged 100.