University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan Copyright By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Economic-Engineering Study of the Feed Manufacturing Industry

An economic-engineering study of the feed manufacturing industry of Montana by Kenneth Wayne Eubanks A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Agricultural Economics Montana State University © Copyright by Kenneth Wayne Eubanks (1962) Abstract: The State of Montana today is faced with the twin considerations of an abundant supply of barley and a large number of cattle. Further, the feed manufacturing industry has embarked on a general program of expansion. There is a possibility of greatly expanding the livestock feeding industry in Montana because of a growing, demand for finished livestock products in Montana and on the Pacific Coast. The general expansion of the feed manufacturing industry brings to focus three principal problems. The first problem is related to the supply of barley and the necessity of making an economical disposition thereof. This disposition can be made through increased feeding operations for livestock, and also, in the case of the Montana industry, for the wintering of cattle. Then secondly, the feed manufacturing industry needs to have available the necessary information concerning the location, size, and type of plant arrangement best suited to the State of Montana. Thirdly, there is a need to make available detailed cost information so that the managers of plants presently in operation in Montana may better judge the efficiencies of their own operations. Most managers of the feed mills possess only a rough approximation as to total cost and little or no information at all concerning the cost of production at the several stages along the production cycle. -

American Feed Industry Association

AMERICAN FEED INDUSTRY ASSOCIATION SPRING 2018 EDITION afia.org Journal New Study Shows Animal Food Industry Contributes Billions to U.S. Economy Table of Contents 12 ON THE COVER NEW STUDY SHOWS ANIMAL 17 FOOD INDUSTRY CONTRIBUTES BILLIONS TO U.S. ECONOMY FEATURES FEED REGULATORY 3 OUTLOOK FOR 2018 TO NEGOTIATE OR TO RENEGOTIATE? 12 THAT IS THE 3 QUESTION. CORN, SOY TOP LIST 19 OF INGREDIENTS 19 USED IN LIVESTOCK, 41 POULTRY FEED HOW DO AFIA MEMBERS RECRUIT 41 AND RETAIN NEW EMPLOYEES? Pictured on cover: Over 944,000 people working at more than 6,200 animal Send Us Your Story Ideas! food manufacturing facilities across America, like this one in LaVergne, Have a suggestion for a topic we should cover? Tennessee, are stimulating the economy and helping keep animals fed. Email Victoria Broehm at [email protected] or call (703) 558-3579. EDITOR: Victoria Broehm INSIDE THIS ISSUE ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Codi Coulter president’s message DESIGNER: Raamezah Ahmad 1-4 legislative & regulatory outlook Joel G. Newman President and CEO 5-7 l&r leadership actions Raamezah Ahmad 8 osha/dot/epa updates Graphic and Web Design Coordinator Victoria Broehm 9 aafco update Director, Communications Erica Burson 10 state update Membership Assistant 12 international trade Kori Chung Legislative and Regulatory Assistant 13-14 guest column Codi Coulter ifeeder Communications Coordinator 16-20 Shakera Daley 21-22 committee corner Accounting and Administrative Coordinator Paul Davis, Ph.D. 23 safe feed/safe food Director, Quality, Animal Food Safety and Education Gary -

9 Processing of Coffee Pulp: Chemical Treatments

The International Development Research Centre is a public corporation created by the Parliament of Canada in 1970 to support research designed to adapt science and technology to the needs of developing countries. The Centre's activity is concentrated in five sectors: agriculture, food and nutrition sciences; health sciences; information sciences; social sciences; and communications. IDRC is financed solely by the Government of Canada; its policies, however, are set by an international Board of Governors. The Centre's headquarters are in Ottawa, Canada. Regional offices are located in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East. La edici6n espa1'1.ola de esta publicaci6n tambien se encuentra disponible. © 1979 Intern ati onal Development Research Centre Postal Address: Box 8500, Ottawa, Canada KI G 3H9 Head Office: 60 Queen Street, Ottawa Braham, J. E. Bressani , R. IDRC- 108e Coffee pulp: compos1t1 on, technology, and utili zation. Ottawa, Ont. , IDRC, 1979. 95 p. : ill. IDRC publication/. Compilation on the use of /coffee/ pulp (/agri cultural waste/) as animal /feed/, particul arl y in /Central America/ - discusses coffee /plant producti on/, /food composition/ of coffee by-products; /agri product processing/, ensil ing (/storage/) and /drying/; antiphysiological factors, such as caffeine and /acid/s, and their impact on /animal nutrition/ and /animal production/ . / Bibliography/, /statisti cal data/. UDC: 633 .73.002.6 ISBN: 0-88936- 190-8 Microfi che edition avail able Technical Editor: Michael Graham IDRC-108e Coffee Pulp Composition, Technology, and Utilization Editors: J.E. Braham and R. Bressani Institute of Nutrition of Central America and Panama 1 1The Institute of Nutrition of Central America and Panama (INCAP) is a scientific international organization created to study the nutritional problems of the region, seek ways and means of solving these problems, and provide member governments with advice and cooperation. -

A Practical Guide to Nutrition, Feeds, and Feeding of Catfish

A Practical Guide to Nutrition, Feeds, and Feeding of Catfish Bulletin 1041 -- March 1996 Edwin H. Robinson Meng H. Li Fishery Biologist Research Assistant Delta Branch Experiment Station Delta Branch Experiment Station Stoneville, Mississippi Stoneville, Mississippi Contents Preface Acknowledgments Introduction Nutrition Energy Utilization and expression Requirements Nutrients Carbohydrates Lipid Protein and amino acids Vitamins Minerals Digestion Feeds Feed ingredients Protein supplements Energy supplements Premixes Feed formulation Feed Manufacture Nutritional Considerations Nonnutritional Considerations Manufacturing Processes Receiving and storage Grinding, batching, and mixing Steam pelleting Extrusion Drying and cooling Fat coating, storage, screening, and delivery Pellet grinding or crumbling Quality Assurance Feed formulation Ingredients Manufacturing Finished feed Feeding Natural Foods Warm Weather Feeding Fry Fingerlings Food fish Broodfish Winter Feeding Fingerlings and food fish Broodfish Feeding Diseased Fish Medicated feeds Considerations Effect of Feeds on Sensory Quality of Processed Catfish Flavor Appearance Fattiness Compensatory Growth List of Tables 1. Recommended dietary protein levels for various sizes of catfish 2. Amino acid requirements of channel catfish 3. Vitamin deficiency signs and minimum dietary levels required to prevent signs of deficiency in catfish 4. Mineral deficiency signs and minimum dietary levels required to prevent deficiency signs in catfish 5. Average apparent protein digestibility coefficients for catfish 6. Average apparent amino acid availabilities (expressed as a percentage) for various feedstuffs determined for catfish 7. Average percentage apparent digestible energy determined for catfish 8. Average apparent digestion coefficients of lipids and carbohydrates determined for catfish 9. Average percentage apparent availability of phosphorus determined for catfish 10. Feed ingredients used in commercial catfish feeds 11. Nutrients recommended for catfish grow-out feeds 12. -

Viability of Weed Seeds in Feed Pellet Processing1

Reprinted with permission from: The Journal of Range Management. March 1998. 51(2):181-185, 10 ref. Published and copyrighted by: Society for Range Management. http://srm.org E-mail: [email protected] Viability of weed seeds in feed pellet processing1 S. DENNIS CASH, DAVID L. ZAMORA, and ANDREW W. LENSSEN Authors are Extension Agronomist, Department of Plant, Soil and Environmental Sciences, Montana State University, Bozeman, Mont.; independent consultant, Boise, Ida.; and Research Assistant Professor, Department of Entomology, Montana State University, Bozeman, Mont., respectively. Published with the approval of the Director of the Mont. Agr. Exp. Sta. as Journal Series J-5075. Abstract: Federal and state agencies in several western states now require the use of noxious weed-free or noxious weed seed-free forage to hinder the spread of noxious weeds. Forage can be certified as noxious weed-free through state administered programs. Processed feeds such as pellets or cubes made from noncertified hay and uncleaned grain are some of the forage products that may be potential sources of weed infestations. This study was conducted to determine levels of weed seed contamination in alfalfa hay/grain feed pellets manufactured with commercial-grade equipment. Seeds of whitetop [Cardaria draba (L.) Hand.], spotted knapweed (Cen- taurea maculosa Lam.), Canada thistle [Cirsium arvense (L.) Scop.], leafy spurge (Euphorbia esula L.), and common yellow sweetclover [Melilotus officinalis (L.) Lam.) were added in known quantities to alfalfa/grass mixed bay and to barley. The hay was ground in a hammermill through a screen with 7.9-mm diameter perforations, and the barley was ground to pass through a 2.4-mm screen. -

Animal Feed/Fodder Market Actors Mapping and the Agribusiness of Livestock Feed in Northwest Syria

Animal Feed/Fodder Market Actors Mapping and the Agribusiness of Livestock Feed in Northwest Syria May 2021 A poultry farm destroyed by an air strike in Syria. Photo courtesy of NGO Independent Arabia. Animal Feed/Fodder Market Actors Mapping Study on North West Syria Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION 4 II. BACKGROUND 4 III. Study Objectives 5 IV. Methodology 6 V. Results 7 A. Traders/Commercial Feed Industry Assessment (Ownership and Type of Business) 7 B. Fodder and Animal Feed Producer Factory Status 8 C. Fodder and Animal Feed Production and Sales 9 D. Production Cost per Metric Ton 12 E. Production Change 14 F. Needed Support to Sustain or Improve Business Operations. 15 G. Availability and Source of Commercial Products 15 H. Seasonal Prices of Raw Materials for Animal Feed 18 I. Quality Control across the fodder/animal feed value chain 25 J. Taxes 25 VI. DISCUSSION 28 VII. CONCLUSION 29 VIII. RECOMMENDATIONS 29 List of Tables Table 1: Estimated facility rehabilitation cost. 9 Table 2: Fodder Average Production Cost 12 2 Animal Feed/Fodder Market Actors Mapping Study on North West Syria List of Figures Figure 1: Number and Type of Market Actors Reached per Governorate 7 Figure 2: Infrastructure Rehabilitation Needs 9 Figure 3: Number of Market Actors that Produce/Sell Green Fodder 9 Figure 4: Average Monthly Production/Sales of Fodder (MT/Month) 10 Figure 5: Number of Market Actors that Produce/Sell Animal Feed 10 Figure 6: Average Monthly Production/Sales of Animal Feed for Cow and Sheep (MT/Month) 11 Figure 7: Average Monthly Production/Sales -

Premixtures Fefana Publication

Fefana Publication Premixtures Fefana Publication Premixtures Contributors: FEFANA Working Group Premixtures, and in particular: Peter Fidder, Nutreco Philippe Becquet, DSM Cédric Martin, DSM Mario Döpker, Miavit Juan José Mallo, Norel y Nature ISBN 978-2-9601289-0-1 © FEFANA 2013 -03- Table of Contents Preamble 7 b. pH 17 Introduction 9 c. Moisture 18 d. Bulk density 18 e. Reactivity 18 I. THE VARIOUS TYPES OF f. Contaminants 18 PREMIXTURES 10 g. Solubility in water 19 h. Hygroscopicity 19 1. Product forms 11 i. Shelf life 19 2. Product functions 12 j. Flowability 19 3. Different constraints 13 k. Dustiness 19 II. SOURCING AND III. FORMULATION OF PROCUREMENT 13 PREMIXTURES 20 1. Legal, Quality system, 1. Product types 20 Customer requirements 13 a. Pre-dilutions 21 a. Registered and approved b. Specific blends 21 feed business operators 13 c. Complex premixtures 22 b. Legal requirements 14 c. Quality system 15 2. Nutritional aspects 23 d. Customer requirements 15 3. Characteristics of the ingredients 24 e. Sourcing of incoming 4. Choice of carrier(s) 25 materials 15 5. Handling properties 27 6. Safety and quality aspects 27 2. Ingredients specifications 7. Regulatory requirements 28 (feed additives, feed 8. Specific customer requirements 29 materials used as carriers) 9. Logistic aspects 29 and packaging materials 16 10. Conclusions 29 a. Management requirements IV. MANUFACTURING 30 for premixture ingredients 16 b. Specifications for 1. Intake and storage 30 packaging materials 16 2. Suitable equipment 31 3. Conveying 33 3. Specific requirements for 4. Weighing and dosing 34 premix ingredients 17 5. Premixture mixing (types of mixers) 36 a. -

Commercial Feed Laws and Regulations

CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FOOD AND AGRICULTURE INSPECTION SERVICES DIVISION FOOD AND AGRICULTURAL CODE DIVISION 7, CHAPTER 6. COMMERCIAL FEED AND CALIFORNIA CODE OF REGULATIONS TITLE 3, DIVISION 4, CHAPTER 2, SUBCHAPTER 2. COMMERCIAL FEED 2020 REVISIONS FOOD AND AGRICULTURAL CODE Article 10 Section 15053(a) Article 11 Section 15061(a), (d) Section 15061(a), (c) 2019 REVISIONS FOOD AND AGRICULTURAL CODE Article 5 Section 14991(a), (b) Article 9 Section 15042 Article 10 Section 15056 Article 12 Section 15071 (a), (b), (c) Section 15071.1. (a), (b), (c), (d), (e), (f) Section 15071.3. (a), (b) Section 15071.4. Section 15071.5. Section 15075 (a), (b) Section 15082 (a), (b), (c) Article 13 Section 15091 Section 15092 Note: SEC. 10. Section 15081 of the Food and Agricultural Code is repealed. Effective 01/01/2019 2016 REVISIONS FOOD AND AGRICULTURAL CODE Article 1 Section 14902.5 Article 4 Section 14978.2 (d) 2015 REVISIONS FOOD AND AGRICULTURAL CODE Article 11 Section 15061(d) CALIFORNIA CODE OF REGULATIONS Title 3 Section 2751 Revised January 27, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOOD AND AGRICULTURAL CODE ARTICLE 1. GENERAL PROVISIONS [SECTIONS 14901 – 14904] ............................. 1 ARTICLE 2. DEFINITIONS [SECTIONS 14921 – 14939] .............................................. 2 ARTICLE 3. FUNDS [SECTIONS 14961 – 14963] ......................................................... 3 ARTICLE 4. FEED INSPECTION ADVISORY BOARD [SECTIONS 14971 – 14979] ... 3 ARTICLE 5. LABELS [SECTIONS 14991 – 14996] ....................................................... 7 ARTICLE 6. STANDARDS AND TOLERANCES [SECTION 15011 – 15011] ................ 8 ARTICLE 7. INSPECTION AND ANALYSIS [SECTION 15021 – 15021]....................... 8 ARTICLE 8. MISLABELING [SECTION 15031 – 15031]................................................ 8 ARTICLE 9. ADULTERATION [SECTIONS 15041 – 15042] ......................................... 9 ARTICLE 10. LICENSES [SECTIONS 15051 – 15056] ................................................. 9 ARTICLE 11. -

Detailed Feasibility Report

DETAILED FEASIBILITY REPORT Animal Feed Unit in conformity with The Royal Government of Bhutan’s Vision of Achieving Economic Self-Reliance June 2015 Ministry of Economic Affairs Royal Government of Bhutan DETAILED FEASIBILITY REPORT - Animal Feed Unit CONTENT Section Topic Page Abbreviations and Definitions 4 1.0 Executive Summary 6 2.0 Justification of the project 8 2.1 The need for the project 8 2.2 Competition Analysis 11 3.0 Market Analysis 12 3.1 Structure of the industry 12 3.2 Demand vs. Supply 13 3.3 Pricing & Marketing Strategies 13 3.4 Technological changes that could impact costing 15 3.5 Competitiveness of the project 15 3.6 Special attributes desired by target customers 15 Terms & conditions and product specifications desired by target 3.7 15 customers 3.8 Packaging & Transportation 16 3.9 Assessment of Comparative Advantage 17 3.10 Potential for Marketing Collaboration 17 4.0 Resource 18 4.1 Sources of Inputs Including Water 18 4.2 Comparative Analysis of Critical Inputs 18 4.3 Sources of Raw Material 18 4.4 Availability of Manpower &Skills 22 4.5 Need for Skill Development 22 5.0 The Plant 23 5.1 Choice of Technology 23 5.2 Source 24 5.3 Rate of Consumption of Power, Fuel, Utilities &Consumables 26 5.4 Raw Material Consumption 26 5.5 Manpower Requirement and Organization Chart 27 5.6 Specification of Product and Byproduct 27 5.7 Extent of Technical Assistance NeededIncluding Training 28 6.0 Plant Location & Infrastructure 29 6.1 Raw Material Availability 29 2 DETAILED FEASIBILITY REPORT - Animal Feed Unit 6.2 Availability -

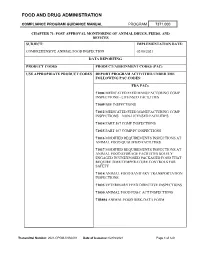

Compliance Program 7371.000

FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION COMPLIANCE PROGRAM GUIDANCE MANUAL PROGRAM 7371.000 CHAPTER 71: POST APPROVAL MONITORING OF ANIMAL DRUGS, FEEDS, AND DEVICES SUBJECT: IMPLEMENTATION DATE: COMPREHENSIVE ANIMAL FOOD INSPECTION 02/08/2021 DATA REPORTING PRODUCT CODES PRODUCT/ASSIGNMENT CODES (PAC) USE APPROPRIATE PRODUCT CODES REPORT PROGRAM ACTIVITIES UNDER THE FOLLOWING PAC CODES: FDA PACs 71004 MEDICATED FEED MANUFACTURING CGMP INSPECTIONS - LICENSED FACILITIES 71009 BSE INSPECTIONS 71012 MEDICATED FEED MANUFACTURING CGMP INSPECTIONS – NON-LICENSED FACILITIES 71014 PART 507 CGMP INSPECTIONS 71015 PART 507 CGMP/PC INSPECTIONS 71016 MODIFIED REQUIREMENTS INSPECTIONS AT ANIMAL FOOD QUALIFIED FACILITIES 71017 MODIFIED REQUIREMENTS INSPECTIONS AT ANIMAL FOOD STORAGE FACILITIES SOLELY ENGAGED IN UNEXPOSED PACKAGED FOOD THAT REQUIRE TIME/TEMPERATURE CONTROLS FOR SAFETY 71018 ANIMAL FOOD SANITARY TRANSPORTATION INSPECTIONS 71023 VETERINARY FEED DIRECTIVE INSPECTIONS 71030 ANIMAL FOOD FD&C ACT INSPECTIONS 71R894 ANIMAL FOOD RISK-DATA FORM Transmittal Number: 2021-CPGM-CVM-001 Date of Issuance: 02/08/2021 Page 1 of 120 PROGRAM 7371.000 STATE PACs 71S004 STATE CONTRACT MEDICATED FEED MANUFACTURING CGMP INSPECTIONS – LICENSED FACILITIES 71S011 STATE CONTRACT BSE INSPECTIONS 71S012 STATE CONTRACT MEDICATED FEED MANUFACTURING CGMP INSPECTIONS – NON- LICENSED FACILITIES 71S014 STATE CONTRACT PART 507 CGMP INSPECTIONS 71S015 STATE CONTRACT PART 507 CGMP/PC INSPECTIONS 71S016 STATE CONTRACT MODIFIED REQUIREMENTS INSPECTIONS AT ANIMAL FOOD QUALIFIED FACILITIES -

SCIENZE DEGLI ALIMENTI Quality and Safety of Oils and Fats Obtained

Allma Mater Studiiorum – Uniiversiità dii Bollogna DOTTORATO DI RICERCA SCIENZE DEGLI ALIMENTI Ciclo XX Settore/i scientifico disciplinari di afferenza: AGR 15 TITOLO TESI Quality and safety of oils and fats obtained as co-products or by-products of the food chain and destined to animal production Presentata da: Dott. Giovanni Pignoli Coordinatore Dottorato Relatore Prof. Claudio Cavani Prof. Giovanni Lercker Correlatore Dott.ssa Maria Teresa Rodriguez Estrada Esame finale anno 2008 Easy PDF Creator is professional software to create PDF. If you wish to remove this line, buy it now. INDEX 1. AIM AND DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT 1 2. INTRODUCTION 4 2.1. FEEDING FAT COMPOSITION AND QUALITY 6 2.2. PRESENCE OF CONTAMINANT IN FEEDING FATS AND MEAT PRODUCTS TURE OF FATTY ACIDS 7 2.2.1 Effects of contaminants on animal health 9 2.3. FEEDSTOCKS 10 2.3.1 Acid oils from chemical refining (AOCHE) 10 2.3.2 Acid oils from physical refining (AOPHY) 12 2.3.3 Lecithin (LECI) 15 2.3.4 Recycled cooking oils (RECY) 17 2.3.5 Animal fats (ANFA) 19 2.3.6 Oils extracted from exhausted bleaching earths (EBE) 20 2.3.7 Fish oils (FISH) 22 2.3.8 Hydrogenated fats from by-products (HYBY) 23 2.3.9 Fatty acid calcium soaps (FACS) 24 2.3.10 Miscellaneous products (MIX) 25 2.4 CHEMICAL DEGRADATIONS IN FEEDING FATS 27 2.4.1 Oxidation 29 2.4.2 Fatty Acids Isomerization 32 2.4.2.1 Trans Fatty Acid 32 2.4.2.2 Origin of TFA 35 2.4.2.3 TFA Effects on Health 38 Easy PDF Creator is professional software to create PDF. -

American Feed Industry Association

AMERICAN FEED INDUSTRY ASSOCIATION FALL 2015 EDITION www.afia.org Journal Featuring SigningTPATPA of ON THE COVER TPA PASSAGE Contents 11 MOVES US FORWARD TO A WORLD OF POSSIBILITIES Signed into law June 29 FEATURES VETERINARY FEED DIRECTIVE FINAL 7 RULE PUBLISHED AFIA concerned with VFD recordkeeping requirements AFIA ATTENDS WHITE HOUSE 8 ANTIBIOTIC FORUM AFIA disagrees with Administration’s message on “hormone-free” GUEST COLUMN: ROB SHEFFER 19 An overview of the 2015-16 Chairman’s goals and initiatives AFIA PISC SPEAKERS ECHO 39 IMPORTANT MESSAGE Perception Equals Reality EDITOR: Miranda McDaniel DESIGNER: Allison Crompton Joel G. Newman INSIDE THIS ISSUE President and CEO president’s message Allison Crompton 1 leadership actions Graphic Design and Website Specialist Shakera Daley 3 legislative outlook Accounting and Administrative Coordinator fsma update Gary Huddleston 6 Manager, Feed Manufacturing Safety and 11 international trade Environmental Affairs Paul Keppy 12 epa/osha update Government Affairs Specialist 13 state update Steve Kopperud 15 aafco Government Affairs Consultant Cassie Kusmisz 16 codex Communications Specialist Miranda McDaniel 18 guest column Manager, Communications 21 member of the year Jessica Morse 22 ifeeder Manager, Meetings and Events Leanna Nail 24 committee corner Director, Administration sustainability Sarah Novak 25 Vice President, Membership and Public Relations 26 safe feed/safe food Christina Redding 29 board of directors Membership Assistant Veronica Rovelli 31 career center Director, Meetings and