Health and People with Usher Syndrome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Screening Guide for Usher Syndrome

Screening Guide for Usher Syndrome Florida Outreach Project for Children and Young Adults Who Are Deaf-Blind Bureau of Exceptional Education and Student Services Florida Department of Education 2012 This publication was produced through the Bureau of Exceptional Education and Student Services (BEESS) Resource and Information Center, Division of Public Schools, Florida Department of Education, and is available online at http://www.fldoe.org/ese/pub-home.asp. For information on available resources, contact the BEESS Resource and Information Center (BRIC). BRIC website: http://www.fldoe.org/ese/clerhome.asp Bureau website: http://fldoe.org/ese/ Email: [email protected] Telephone: (850) 245-0475 Fax: (850) 245-0987 This document was developed by the Florida Instructional Materials Center for the Visually Impaired, Outreach Services for the Blind/Visually Impaired and Deaf/Hard-of-Hearing, and the Resource Materials and Technology Center for the Deaf/Hard-of-Hearing, special projects funded by the Florida Department of Education, Division of Public Schools, BEESS, through federal assistance under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Part B, in conjunction with the Florida Outreach Project for Children and Young Adults Who Are Deaf- Blind, H326C990032, which is funded by the Office of Special Education Programs, U.S. Department of Education. Information contained within this publication does not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Education. Edited by: Susan Lascek, Helen Keller National Center Emily Taylor-Snell, Florida Project for Children and Young Adults Who Are Deaf-Blind Dawn Saunders, Florida Department of Education Leanne Grillot, Florida Department of Education Adapted with permission from the Nebraska Usher Syndrome Screening Project (2002) Copyright State of Florida Department of State 2012 Authorization for reproduction is hereby granted to the state system of public education consistent with section 1006.03(2), Florida Statutes. -

A Molecular and Genetic Analysis of Otosclerosis

A molecular and genetic analysis of otosclerosis Joanna Lauren Ziff Submitted for the degree of PhD University College London January 2014 1 Declaration I, Joanna Ziff, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Where work has been conducted by other members of our laboratory, this has been indicated by an appropriate reference. 2 Abstract Otosclerosis is a common form of conductive hearing loss. It is characterised by abnormal bone remodelling within the otic capsule, leading to formation of sclerotic lesions of the temporal bone. Encroachment of these lesions on to the footplate of the stapes in the middle ear leads to stapes fixation and subsequent conductive hearing loss. The hereditary nature of otosclerosis has long been recognised due to its recurrence within families, but its genetic aetiology is yet to be characterised. Although many familial linkage studies and candidate gene association studies to investigate the genetic nature of otosclerosis have been performed in recent years, progress in identifying disease causing genes has been slow. This is largely due to the highly heterogeneous nature of this condition. The research presented in this thesis examines the molecular and genetic basis of otosclerosis using two next generation sequencing technologies; RNA-sequencing and Whole Exome Sequencing. RNA–sequencing has provided human stapes transcriptomes for healthy and diseased stapes, and in combination with pathway analysis has helped identify genes and molecular processes dysregulated in otosclerotic tissue. Whole Exome Sequencing has been employed to investigate rare variants that segregate with otosclerosis in affected families, and has been followed by a variant filtering strategy, which has prioritised genes found to be dysregulated during RNA-sequencing. -

Etiologies and Characteristics of Deaf-Blindness

Etiologies and Characteristics of Deaf-Blindness Kathryn Wolff Heller, R.N., Ph.D. Geor gia State Uni ver sity Cheryl Ken nedy Uni ver sity of Pitts burgh Edited by: Louis Cooper , M.D. Law rence T. Eschelman, M.D., P.C. James W. Long, M.D., P.C. Rosanne K. Silberman, Ed., D. Contents Pref ace··························3 Sec tion I Foun da tions ······················5 Chap ter 1 Def i ni tions and Ter mi nol ogy Per tain ing to Deaf-Blind ness ···················6 Chap ter 2 Nor mal Anatomy of the Eye and Ear ········16 Chap ter 3 Common Disor ders of the Eye and Ear ·······22 Sec tion II Causes of Deaf-Blind ness ···············36 Chap ter 4 He red i tary Syn dromes and Dis or ders········37 Chap ter 5 Con gen i tal In fec tions and Teratogens ········50 Chap ter 6 Prematurity and Small for Gesta tional Age·····65 Chap ter 7 Ad ven ti tious Con di tions ···············68 APPENDIX Ref er ences························75 Pref ace here are sev eral dis or ders, syn dromes, in fec tious dise ases, and ad ven ti tious con - di tions that may re sult in an in di vid ual be ing deaf-blind. As a re sult of these var i - Tous eti ol o gies, an in di vid ual who is deaf-blind may ex hibit a range of vi sion and hear ing losses. Sen sory loss may range from mild im pair ment to to tal loss of the abil ity to see and/or hear. -

The Functional Hearing Inventory

THE FUNCTIONAL HEARING INVENTORY: CRITERION-RELATED VALIDITY AND INTERRATER RELIABILITY by PAMELA M. BROADSTON, B.S., M.A. A DISSERTATION IN SPECIAL EDUCATION Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Approved December, 2003 Copyright 2003, Pamela M. Broadston ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I thank my Lord, Jesus Christ for opening the door that provided the opportunity for me to obtain this degree. Without His almighty love and endless grace, I would never have achieved this milestone. This milestone could also never have been achieved without the love and support of my family. I cannot proceed without first acknowledging them: to my parents who provided constant love and support throughout this entire endeavor; to my brother Bob, without his financial support I would probably still be working on my master's degrees one class at a time; to my sister, who allowed me to vent and provided sound advice during trying times; to my baby brother, Jeff, thanks for believing in me. I most gratefully thank my dissertation committee for their wisdom, support, and constructive criticism. Their dedication and skilled instruction were vital to the completion of this project. They include: Dr. Carol Layton who provided me with her expertise and guidance in diagnostics and assessment, Dr. Nora Griffm-Shirley who got me hooked on O&M, and Dr. Robert Kennedy who patiently explained and re-explained statistics, time and time again. Last but not least, I want to thank my chair. Dr. Roseanna Davidson, for providing the resources and opportunities that enhanced my doctoral studies and for her expertise and guidance into the field of deafblindness. -

Good Practice Guide for Social Workers in England and Wales Working with Adults with Acquired Hearing Loss

Good Practice Guide for Social Workers in England and Wales Working with Adults with Acquired Hearing Loss Brian Crellin, Peter Simcock & Jacqui Bond www.basw.co.uk Contents Forewords ..................................................................................................................................... 3 About the Authors ...................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 5 Definitions ................................................................................................................................... 6 What is acquired hearing loss? ...................................................................................................... 6 Types of Acquired Hearing Loss ................................................................................................... 9 Registration and Acquired Hearing Loss ..................................................................................... 9 Incidence and Prevalence of Acquired Hearing Loss ........................................................ 10 Medical Assessment of Hearing Loss ....................................................................................12 Tinnitus and its Treatment .............................................................................................................13 Meniere’s Disease and its Treatment ......................................................................................... -

Dba - Deafblind Australia

DBA - DEAFBLIND AUSTRALIA Deafblind Australia DBA is a peak national organisation for the deafblind community in Australia. DBA welcomes the opportunity to comment on the inquiry into Hearing Health and Wellbeing to enable Government to engage with deafblind people needs and their supports to ensure they are provided with the care necessary to support their health and wellbeing. ABOUT DEAFBLIND AUSTRALIA (DBA) DBA was established in 1993 at the National Deafblind Conference in Melbourne, Victoria. This council was established to provide: security; sense of belonging; freedom of speech; and represent the Australian deafblind community and their supporting networks. At present, ADBC represents an estimated 300,000 deafblind people including those with multi disabilities, their families and organisations working the deafblind field. SUBMISSION INTO HEARING HEALTH AND WELLBING AFFECTING DEAFBLIND PEOPLE Throughout this submission, the terms deafblind, combined vision and hearing impairment and dual sensory impairment will be used interchangeably as all three are used to describe people with deafblindness. Deafblindness is described by Deafblind Australia as: “a unique and isolating sensory disability resulting from the combination of both a hearing and vision loss or impairment which significantly affects communication, socialisation mobility and daily living. People with deafblindness form a very diverse group due to the varying degrees of their vision and hearing impairments plus possible additional disabilities. This leads to a wide range of communication methods including speech, oral/aural communication, various forms of sign language including tactile, Deafblind fingerspelling, alternative and augmentative communication and print/ braille” Please see below responses to the terms of reference of the inquiry. 1. -

Deaf-Blindness; Rubella, CHARGE Syndrome, Usher’S Syndrome, Genetic Disorders, Accident and / Or Illness Are Some of the More Common Ones

Deafblindness Deafblindness is a combination of vision and hearing loss. Deafblindness encompasses a spectrum from mildly hard of hearing plus mildly visually impaired to totally deaf and blind. It is rare that an individual with deafblindness would be completely blind and completely deaf. Individuals who have a combined vision and hearing loss have unique communication, learning, and mobility challenges due to their dual sensory loss. Deafblindness is a unique and diverse condition due to the wide range of sensory capabilities, possible presence of additional disabilities, and the age of onset for the vision and hearing loss. A child with deafblindness would include the infant who has a diagnosis of Retinopathy of Prematurity (a retinal condition that is associated with premature birth) and has an acquired hearing loss due to meningitis at age two. Another person with deafblindness may have been born with a profound hearing loss and developed a later vision loss due to a genetic condition called retinitis pigmentosa. There are many causes of deaf-blindness; Rubella, CHARGE Syndrome, Usher’s Syndrome, genetic disorders, accident and / or illness are some of the more common ones. Deafblindness occurs in three of 100,000 births. In Colorado, just over 140 children and youth (ages birth through 21 years) have been identified as having both a vision and hearing loss. These individuals are eligible for free technical assistance through the Colorado Services for Children and Youth with Combined Vision and Hearing Loss Project, located at the Colorado Department of Education. This project provides technical assistance which supports Colorado children and youth, birth to 21 years, who have BOTH a vision and hearing impairment. -

We Hear with Our Brain As the Same As Our Ears

Scholarly Journal of Otolaryngology DOI: 10.32474/SJO.2019.02.000133 ISSN: 2641-1709 Opinion We Hear With our Brain as the same as our Ears Alireza Bina* Starwood Audiology, USA *Corresponding author: Alireza Bina, Starwood Audiology, USA, Email: Received: May 13, 2019 Published: May 21, 2019 Abstract There are some studies which confirmed that dysfunction in Central Nervous System (CNS) may cause a malfunction in the Peripheral Auditory system (Cochlea_ Auditory Nerve, Auditory Neuropathy), but the question is could Brain Disorder without any lesion in Cochlea and/or Auditory nerve cause Sensorineural Hearing Loss? It seems that there are a lot of Sensorineural hearing loss which they have neither Sensory nor Neural lesion, Brain is involved causing them. We deal with this subject in this paper and we propose a new theory that External Ear Canal is not the only input of Auditory Signals, Sounds could receive by the head and Cerebral Cortex and approach to the Cochlea (Backward Auditory input of Sounds). Discussion because of correlation between them this occurred, so not only There are some studies that verified Otosclerosis and Meniere disorder in Central Auditory system may cause peripheral hearing Diseases which are Peripheral pathologies initiated from CNS [1,2]. loss malfunction in other parts of Brain may involve in causing Increasing Cortisol Level and lack of Dopamine in Hypothalamus hearing loss [3]. Neurofibromatosis type II is a genetic condition is involved in Meniere Disease and in Otosclerosis infection of CNS which may -

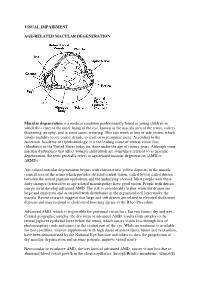

Visual Impairment Age-Related Macular

VISUAL IMPAIRMENT AGE-RELATED MACULAR DEGENERATION Macular degeneration is a medical condition predominantly found in young children in which the center of the inner lining of the eye, known as the macula area of the retina, suffers thickening, atrophy, and in some cases, watering. This can result in loss of side vision, which entails inability to see coarse details, to read, or to recognize faces. According to the American Academy of Ophthalmology, it is the leading cause of central vision loss (blindness) in the United States today for those under the age of twenty years. Although some macular dystrophies that affect younger individuals are sometimes referred to as macular degeneration, the term generally refers to age-related macular degeneration (AMD or ARMD). Age-related macular degeneration begins with characteristic yellow deposits in the macula (central area of the retina which provides detailed central vision, called fovea) called drusen between the retinal pigment epithelium and the underlying choroid. Most people with these early changes (referred to as age-related maculopathy) have good vision. People with drusen can go on to develop advanced AMD. The risk is considerably higher when the drusen are large and numerous and associated with disturbance in the pigmented cell layer under the macula. Recent research suggests that large and soft drusen are related to elevated cholesterol deposits and may respond to cholesterol lowering agents or the Rheo Procedure. Advanced AMD, which is responsible for profound vision loss, has two forms: dry and wet. Central geographic atrophy, the dry form of advanced AMD, results from atrophy to the retinal pigment epithelial layer below the retina, which causes vision loss through loss of photoreceptors (rods and cones) in the central part of the eye. -

Michigan Ear Institute Otosclerosis

Michigan Ear Institute Michigan Otosclerosis www.michiganear.com 34015-56111-109 BOOK Otosclerosis.indd 1 2/13/18 10:33 AM Dennis I. Bojrab, MD Seilesh C. Babu, MD John J. Zappia, MD, FACS Eric W. Sargent, MD, FACS DOCTORS Eleanor Y. Chan, MD Robert S. Hong, MD Ilka C. Naumann, MD Candice C. Colby, MD Christopher A. Schutt, MD Providence Medical Building 30055 Northwestern Highway Suite 101 Farmington Hills, MI 48334 Beaumont Medical Building LOCATIONS 3555 W. Thirteen Mile Road Suite N-210 Royal Oak, MI 48073 Oakwood Medical Building 18181 Oakwood Blvd. Suite 402 Dearborn, MI 48126 Providence Medical Center 26850 Providence Parkway Suite 130 Novi, MI 48374 248-865-4444 phone 248-865-6161 fax 1 34015-56111-109 BOOK Otosclerosis.indd 1 2/13/18 10:33 AM WELCOME Welcome to the Michigan Ear Institute, one of the nation’s leading surgical groups specializing in hearing, balance and facial nerve disorders. The Michigan Ear Institute is committed to providing you with the highest quality diagnostic and surgical treatment possible. Our highly experienced team of physicians, audiologists and clinical physiologists have established international reputations for their innovative diagnostic and surgical capabilities, and our modern, attractive facility has been designed with patient care and convenience as the foremost criteria. It is our privilege to be able to provide care for your medical problems and we will strive to make your visit to the Michigan Ear Institute a positive and rewarding experience. 3 34015-56111-109 BOOK Otosclerosis.indd 3 2/13/18 10:33 AM OTOSCLEROSIS Otosclerosis is a disease of the middle ear bones and sometimes the inner ear. -

Usher Syndrome and Psychiatric Conditions Associated with the Syndrome Definitions/Classification

KYOVR DeafBlind Conference November 20, 2019 Presenter: Mark Poston, M.A. Overview of Usher Syndrome and Psychiatric Conditions Associated with the Syndrome Definitions/Classification . DeafBlind definition . Congenitally Deaf/HoH, Adventitiously Blind . Congenitally Blind, Adventitiously Deaf/HoH . Congenitally DeafBlind . Adventitiously DeafBlind Learning Objectives . Participants will identify distinguishing clinical features associated with the 3 types of Usher Syndrome . Participants will gain an understanding of etiological factors and the diagnostic process associated with Usher Syndrome . Participants will become familiar with mental health conditions and symptoms sometimes occurring with Usher Syndrome. DeafBlindness: Causes . Multiple Congenital Anomalies . Hydrocephaly . Microcephaly . Fetal Alcohol Syndrome . Maternal Drug Abuse . Prematurity DeafBlindness: Causes . Prenatal Infections . Syphilis . Toxoplasmosis . Rubella . CMV . Herpes . AIDS DeafBlindness: Causes . Post-natal Causes . Asphyxia . Head Injury . Stroke . Encephalitis . Meningitis . Tumors . Metabolic Disorders DeafBlindness: Causes . Psychogenic Causes . Conversion Disorder . Genetic Syndromes . CHARGE . Down’s Syndrome . Trisomy 13 . Usher Syndrome Usher Syndrome . Genetic condition (autosomal recessive) . Sensorineural hearing loss . Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) . Balance issues . Most frequent cause of deaf-blindness . Estimates are 1 in 10 carry some form of the recessive gene . There are at least 10 genes that cause Usher Syndrome . There are 3 types and -

Congenital Deafblindness

Congenital deafblindness Supporting children and adults who have visual and hearing disabilities since birth or shortly afterwards Bartiméus aims to record and share knowledge and experience gained about possibilities for people with visual disabilities. The Bartiméus series is an example of this. Colophon Bartiméus PO Box 340 3940 AH Doorn (NL) Tel. +31 88 88 99 888 Email: [email protected] www.bartimeus.nl Authors: Saskia Damen Mijkje Worm Photos: Ingrid Korenstra ‘This digital edition is based on the first edition with ISBN 978-90-821086-1-3’ Copyright 2013 Bartiméus All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a data retrieval system or made public, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, by photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Although every attempt has been made to reference the literature in line with copyright law, this proved no longer possible in a number of cases. In such cases, Bartiméus asks that you contact them, so that this can be rectified in a second edition. 2 Preface Since 1980, Bartiméus has offered specialised support to people with visual and hearing disabilities, especially those born with visual and hearing disabilities, referred to as congenital deafblindness. Bartiméus staff have had the opportunity to get to know these people intensively over the past 30 years. Many people with deafblindness have lived in the same place for many years and have a permanent and trusted team of caregivers who have been with them during all facets of their daily lives, at both good and bad times.