Dba - Deafblind Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Screening Guide for Usher Syndrome

Screening Guide for Usher Syndrome Florida Outreach Project for Children and Young Adults Who Are Deaf-Blind Bureau of Exceptional Education and Student Services Florida Department of Education 2012 This publication was produced through the Bureau of Exceptional Education and Student Services (BEESS) Resource and Information Center, Division of Public Schools, Florida Department of Education, and is available online at http://www.fldoe.org/ese/pub-home.asp. For information on available resources, contact the BEESS Resource and Information Center (BRIC). BRIC website: http://www.fldoe.org/ese/clerhome.asp Bureau website: http://fldoe.org/ese/ Email: [email protected] Telephone: (850) 245-0475 Fax: (850) 245-0987 This document was developed by the Florida Instructional Materials Center for the Visually Impaired, Outreach Services for the Blind/Visually Impaired and Deaf/Hard-of-Hearing, and the Resource Materials and Technology Center for the Deaf/Hard-of-Hearing, special projects funded by the Florida Department of Education, Division of Public Schools, BEESS, through federal assistance under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Part B, in conjunction with the Florida Outreach Project for Children and Young Adults Who Are Deaf- Blind, H326C990032, which is funded by the Office of Special Education Programs, U.S. Department of Education. Information contained within this publication does not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Education. Edited by: Susan Lascek, Helen Keller National Center Emily Taylor-Snell, Florida Project for Children and Young Adults Who Are Deaf-Blind Dawn Saunders, Florida Department of Education Leanne Grillot, Florida Department of Education Adapted with permission from the Nebraska Usher Syndrome Screening Project (2002) Copyright State of Florida Department of State 2012 Authorization for reproduction is hereby granted to the state system of public education consistent with section 1006.03(2), Florida Statutes. -

Press Release

Ménière's Society for dizziness and balance disorders NEWS RELEASE Release date: Monday 17 September 2018 Getting help if your world is in a spin Feeling dizzy and losing your balance is an all too common problem for many people but would you know what to do and where to get help if this happened to you? A loss of balance can lead to falls whatever your age. Around 30% of people under the age of 65 suffer from falls with one in ten people of working age seeking medical advice for vertigo which can lead to life changing or life inhibiting symptoms. Balance disorders are notoriously difficult to diagnose accurately. Most people who feel giddy, dizzy, light-headed, woozy, off-balance, faint or fuzzy, have some kind of balance disorder. This week (16-22 September 2018) is Balance Awareness Week. Organised by the Ménière's Society, the only registered charity in the UK dedicated solely to supporting people with inner ear disorders, events up and down the country will aim to raise awareness of how dizziness and balance problems can affect people and direct them to sources where they can find support. This year Balance Awareness Week also sees the launch of the world’s first Balance Disorder Spectrum, enabling for the first time easy reference to the whole range of balance disorders in one easy to use interactive web site. Medical science is continuously updating and revising its understanding of these often distressing and debilitating conditions. The many different symptoms and causes of balance disorders mean that there have been few attempts to show what they have in common, until now. -

How Do I Know If I Have a Balance Disorder?

PO BOX 13305 · PORTLAND, OR 97213 · FAX: (503) 229-8064 · (800) 837-8428 · [email protected] · WWW.VESTIBULAR.ORG How Do I Know if I Have a Balance Disorder? This article is adapted from information provided by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communications Disorders, (NIDCD). Millions of individuals have disorders of sensation of spatial disorientation or balance they describe as “dizziness.” imbalance. Experts believe that more than four out of ten Americans will experience an Almost everyone experiences a few episode of dizziness significant enough to seconds of dizziness or disequilibrium at send them to a doctor. some point —for example, when a person stands on a train platform and What can be difficult for both a patient momentarily perceives an illusion of and his or her doctor is that the word moving as a train rushes past. However, “dizziness” is a subjective term. This for some people, symptoms can be means that the word can be used by intense and last a long time, affecting a people to describe different sensations person’s independence, ability to work, they are experiencing, but it is hard for and quality of life. anyone but the person experiencing the symptoms to understand or measure Balance disorders can be caused by the nature or severity of the sensations. medications or certain health conditions, In addition, people tend to use different including problems with the inner ear terms to describe the same kind of (vestibular) organs or the brain. problem. “Dizziness,” “vertigo,” and Dizziness, vertigo, and disequilibrium are “disequilibrium” are often used all symptoms that can result from a interchangeably, even though they have peripheral vestibular disorder (a different meanings. -

Balance Disorder Spectrum Technical Report: January 2018

Balance Disorder Spectrum Technical Report: January 2018 Professor Andrew Hugill Professor Peter Rea College of Science and Engineering The Leicester Balance Centre University of Leicester Department of ENT Leicester, UK Leicester Royal Infirmary [email protected] Leicester, UK Abstract—This paper outlines the technical aspects of the first version of a new spectrum of balance disorders. It describes the II. BALANCE DISORDER SPECTRUM implementation of the spectrum in an interactive web page and proposes some avenues for future research and development. A. Rationale Balance disorders are often both unclear and difficult to Keywords—balance, disorder, spectrum diagnose, so the notion of a spectrum may well prove useful as an introduction to the field. Thanks to existing spectrums (e.g. I. INTRODUCTION autism), the general public is now familiar with the idea of a This project seeks to create an interactive diagnostic tool collection of related disorders ranging across a field that might for the identification of balance disorders, to be used by be anything from mild to severe. The importance of balance clnicians and GPs as well as the wider public. There are three disorders is generally underestimated. The field has suffered main layers to the project: from a fragmented nomenclature and conflicting medical opinions, resulting from a general uncertainty and even • the establishment of the concept of a spectrum of confusion about both symptoms and causes. Terms such as: balance disorders; dizzy, light-headed, floating, woozy, giddy, off-balance, • the creation of an interactive web page providing feeling faint, helpless, or fuzzy, are used loosely and access to the spectrum and its underlying medical interchangeably, consolidating the impression that this is a information; vague collection of ailments. -

Mal De Debarquement Syndrome (Mdds)?

What is Mal de Debarquement Syndrome (MdDS)? MdDS is a rare and life-altering balance disorder that most commonly develops after an ocean cruise or other type of water travel. MdDS is also known as disembarkment disease or persistent landsickness. MdDS also occurs following air/train travel or other motion experiences or spontaneously/in the absence of a motion event. MdDS is a syndrome because it often includes a diverse array of symptoms. The characteristic symptom of MdDS is a persistent sensation of motion such as rocking, swaying and/or bobbing. Other MdDS Symptoms: MAL de • Disequilibrium - a sensation of unsteadiness DEBARQUEMENT or loss of balance • Fatigue; extreme, unusual SYNDROME • Cognitive impairment - difficulty concentrating, confusion, memory loss …a persistent • Anxiety, depression motion and imbalance disorder… • Ataxia – unsteady, staggering gait • Sensitivity to flickering lights, loud or sudden noises, fast or sudden movements, enclosed areas or busy patterns Do you know a person who has • Headaches, including migraine headaches • Heaviness - sensation of gravitational pull of returned from an ocean cruise and the head, body or feet feels like they are still on the boat – • Dizziness months/years later? • Ear pain and/or fullness • Tinnitus – ringing in the ears Perhaps they returned from a • Nausea plane, train or lengthy car ride, and Most MdDS patients feel relief while driving/ it now feels like they are on a ship riding in an auto, airplane, train or other at sea. motion activities. However, the abnormal sensation of motion returns as soon as the They may be suffering from Mal de motion activity is suspended. This is a Debarquement Syndrome (MdDS), helpful feature in the diagnosis of MdDS. -

Bedside Neuro-Otological Examination and Interpretation of Commonly

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.2004.054478 on 24 November 2004. Downloaded from BEDSIDE NEURO-OTOLOGICAL EXAMINATION AND INTERPRETATION iv32 OF COMMONLY USED INVESTIGATIONS RDavies J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004;75(Suppl IV):iv32–iv44. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.054478 he assessment of the patient with a neuro-otological problem is not a complex task if approached in a logical manner. It is best addressed by taking a comprehensive history, by a Tphysical examination that is directed towards detecting abnormalities of eye movements and abnormalities of gait, and also towards identifying any associated otological or neurological problems. This examination needs to be mindful of the factors that can compromise the value of the signs elicited, and the range of investigative techniques available. The majority of patients that present with neuro-otological symptoms do not have a space occupying lesion and the over reliance on imaging techniques is likely to miss more common conditions, such as benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), or the failure to compensate following an acute unilateral labyrinthine event. The role of the neuro-otologist is to identify the site of the lesion, gather information that may lead to an aetiological diagnosis, and from there, to formulate a management plan. c BACKGROUND Balance is maintained through the integration at the brainstem level of information from the vestibular end organs, and the visual and proprioceptive sensory modalities. This processing takes place in the vestibular nuclei, with modulating influences from higher centres including the cerebellum, the extrapyramidal system, the cerebral cortex, and the contiguous reticular formation (fig 1). -

Confirmed Otosclerosis

Biomedical Research and Therapy, 6(3):3034-3039 Original Research Evaluation of balance function in patients with radiologically (CT scan) confirmed otosclerosis Rania Abdulfattah Sharaf1;∗, Rudrapathy Palaniappan2 ABSTRACT Objective: To assess balance function in patients with radiologically confirmed otosclerosis. Meth- ods: Sixteen patients (14 females and 2 males), who attended the Neuro-Otology clinic/ ENT clinics at the Royal National Throat Nose and Ear Hospital, participated in this study. After general medical, audiological and Neuro-Otological examination, patients underwent the caloric and rotational test- ing. Results: Thirteen of the 16 patients had radiologically confirmed otosclerosis (12 females and 1 male). A total of 3 patients (2 females and 1 male) did not have CT confirmation of otosclerosis, and therefore, were excluded from the study. The remaining 13 patients' data were analyzed. Nine patients had a mixed hearing impairment at least on one side, while eight patients had a bilateral mixed hearing loss and one patient had a sensorineural hearing loss on one side. Four patients had a bilateral sensorineural hearing loss. Only 1 patient had a canal paresis (CP) at 35 %. None of the patients had any significant directional preponderance (DP). The patient with significant CP (35%) did not show any rotational asymmetry on impulsive rotation. Eleven patients had a rotational chair test. Only one patient had a significant asymmetry to the right at 25.30% (normal range is <20%). Overall, 18% (n = 2) of the radiologically confirmed otosclerosis patients showed an abnormal bal- ance test, including both caloric and rotational tests. More than 80% (n = 9) of the patients with radiological otosclerosis showed balance symptoms. -

The Functional Hearing Inventory

THE FUNCTIONAL HEARING INVENTORY: CRITERION-RELATED VALIDITY AND INTERRATER RELIABILITY by PAMELA M. BROADSTON, B.S., M.A. A DISSERTATION IN SPECIAL EDUCATION Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Approved December, 2003 Copyright 2003, Pamela M. Broadston ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I thank my Lord, Jesus Christ for opening the door that provided the opportunity for me to obtain this degree. Without His almighty love and endless grace, I would never have achieved this milestone. This milestone could also never have been achieved without the love and support of my family. I cannot proceed without first acknowledging them: to my parents who provided constant love and support throughout this entire endeavor; to my brother Bob, without his financial support I would probably still be working on my master's degrees one class at a time; to my sister, who allowed me to vent and provided sound advice during trying times; to my baby brother, Jeff, thanks for believing in me. I most gratefully thank my dissertation committee for their wisdom, support, and constructive criticism. Their dedication and skilled instruction were vital to the completion of this project. They include: Dr. Carol Layton who provided me with her expertise and guidance in diagnostics and assessment, Dr. Nora Griffm-Shirley who got me hooked on O&M, and Dr. Robert Kennedy who patiently explained and re-explained statistics, time and time again. Last but not least, I want to thank my chair. Dr. Roseanna Davidson, for providing the resources and opportunities that enhanced my doctoral studies and for her expertise and guidance into the field of deafblindness. -

Is There a Link Between Usher Syndrome Type II and Balance Problems Or Vertigo?

Is there a link between Usher syndrome type II and balance problems or vertigo? Information Monitoring Summary Documentary research Josée Duquette, Planning, Programming and Research Officer Francine Baril, Documentation Technician Prepared by Josée Duquette, Planning, Programming and Research Officer October 21st, 2009 Notice to readers The information in the following pages is not intended to be an exhaustive review of the literature. The goal was to make directly relevant selected information more readily available. Accordingly, not all articles or documents dealing with the topic have been reviewed. Authorization to reproduce This document and the accompanying material may be reproduced for clinical, teaching or research purposes with the prior written consent of l’Institut Nazareth et Louis-Braille. Modifying this document and the accompanying material in any way whatsoever is strictly prohibited. Any reproduction in whole or in part of this document and the accompanying material for commercial purposes is strictly prohibited. © Institut Nazareth et Louis-Braille, 2009 SUMMARY Usher syndrome type II is characterized by moderate to severe congenital deafness, normal vestibular function, and retinitis pigmentosa usually appearing in the patient’s late twenties or early thirties. Clinicians in the deaf-blindness program run jointly by the Institut Nazareth et Louis-Braille and the Institut Raymond-Dewar have noticed that certain patients with this form of the syndrome complain of vertigo, dizziness and loss of balance. The literature confirms that there are atypical forms of Usher syndrome type II characterized by, among others, vestibular dysfunction [1-3]. Other cases have also been reported in the scientific literature or anecdotally [7; 8]. -

Good Practice Guide for Social Workers in England and Wales Working with Adults with Acquired Hearing Loss

Good Practice Guide for Social Workers in England and Wales Working with Adults with Acquired Hearing Loss Brian Crellin, Peter Simcock & Jacqui Bond www.basw.co.uk Contents Forewords ..................................................................................................................................... 3 About the Authors ...................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 5 Definitions ................................................................................................................................... 6 What is acquired hearing loss? ...................................................................................................... 6 Types of Acquired Hearing Loss ................................................................................................... 9 Registration and Acquired Hearing Loss ..................................................................................... 9 Incidence and Prevalence of Acquired Hearing Loss ........................................................ 10 Medical Assessment of Hearing Loss ....................................................................................12 Tinnitus and its Treatment .............................................................................................................13 Meniere’s Disease and its Treatment ......................................................................................... -

Deaf-Blindness; Rubella, CHARGE Syndrome, Usher’S Syndrome, Genetic Disorders, Accident and / Or Illness Are Some of the More Common Ones

Deafblindness Deafblindness is a combination of vision and hearing loss. Deafblindness encompasses a spectrum from mildly hard of hearing plus mildly visually impaired to totally deaf and blind. It is rare that an individual with deafblindness would be completely blind and completely deaf. Individuals who have a combined vision and hearing loss have unique communication, learning, and mobility challenges due to their dual sensory loss. Deafblindness is a unique and diverse condition due to the wide range of sensory capabilities, possible presence of additional disabilities, and the age of onset for the vision and hearing loss. A child with deafblindness would include the infant who has a diagnosis of Retinopathy of Prematurity (a retinal condition that is associated with premature birth) and has an acquired hearing loss due to meningitis at age two. Another person with deafblindness may have been born with a profound hearing loss and developed a later vision loss due to a genetic condition called retinitis pigmentosa. There are many causes of deaf-blindness; Rubella, CHARGE Syndrome, Usher’s Syndrome, genetic disorders, accident and / or illness are some of the more common ones. Deafblindness occurs in three of 100,000 births. In Colorado, just over 140 children and youth (ages birth through 21 years) have been identified as having both a vision and hearing loss. These individuals are eligible for free technical assistance through the Colorado Services for Children and Youth with Combined Vision and Hearing Loss Project, located at the Colorado Department of Education. This project provides technical assistance which supports Colorado children and youth, birth to 21 years, who have BOTH a vision and hearing impairment. -

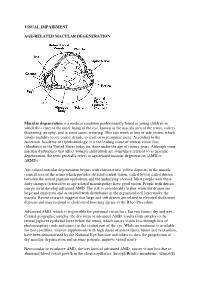

Visual Impairment Age-Related Macular

VISUAL IMPAIRMENT AGE-RELATED MACULAR DEGENERATION Macular degeneration is a medical condition predominantly found in young children in which the center of the inner lining of the eye, known as the macula area of the retina, suffers thickening, atrophy, and in some cases, watering. This can result in loss of side vision, which entails inability to see coarse details, to read, or to recognize faces. According to the American Academy of Ophthalmology, it is the leading cause of central vision loss (blindness) in the United States today for those under the age of twenty years. Although some macular dystrophies that affect younger individuals are sometimes referred to as macular degeneration, the term generally refers to age-related macular degeneration (AMD or ARMD). Age-related macular degeneration begins with characteristic yellow deposits in the macula (central area of the retina which provides detailed central vision, called fovea) called drusen between the retinal pigment epithelium and the underlying choroid. Most people with these early changes (referred to as age-related maculopathy) have good vision. People with drusen can go on to develop advanced AMD. The risk is considerably higher when the drusen are large and numerous and associated with disturbance in the pigmented cell layer under the macula. Recent research suggests that large and soft drusen are related to elevated cholesterol deposits and may respond to cholesterol lowering agents or the Rheo Procedure. Advanced AMD, which is responsible for profound vision loss, has two forms: dry and wet. Central geographic atrophy, the dry form of advanced AMD, results from atrophy to the retinal pigment epithelial layer below the retina, which causes vision loss through loss of photoreceptors (rods and cones) in the central part of the eye.