Rembrandt Exhibition Labels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rembrandt Packet Aruni and Morgan.Indd

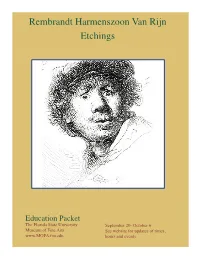

Rembrandt Harmenszoon Van Rijn Etchings Education Packet The Florida State University September 20- October 6 Museum of Fine Arts See website for updates of times, www.MOFA.fsu.edu hours and events. Table of Contents Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn Biography ...................................................................................................................................................2 Rembrandt’s Styles and Influences ............................................................................................................ 3 Printmaking Process ................................................................................................................................4-5 Focus on Individual Prints: Landscape with Three Trees ...................................................................................................................6-7 Hundred Guilder .....................................................................................................................................8-9 Beggar’s Family at the Door ................................................................................................................10-11 Suggested Art Activities Three Trees: Landscape Drawings .......................................................................................................12-13 Beggar’s Family at the Door: Canned Food Drive ................................................................................14-15 Hundred Guilder: Money Talks ..............................................................................................16-18 -

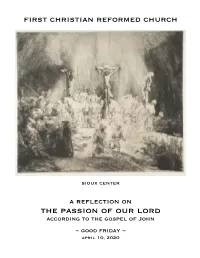

2020 Good Friday Order of Service

first christian reformed church sioux center a reflection on the passion of our lord according to the gospel of John ~ good friday ~ april 10, 2020 order of service Prelude ~ “Were you There” Linker “O Sacred Head” Burkhardt Welcome Call to Worship Today we remember Jesus was crucified. He was pierced for our transgressions. He suffered and died for our iniquities. We remember the sacrifice of our Lord with gratitude because his death gives us life and brings redemption to the world. Let us worship our Savior. Prayer of Invocation O God, who for our redemption gave your only Son to the death of the cross, and by his glorious resurrection delivered us from the power of our enemy: grant us so to die daily to sin, that we may evermore live with him in the joy of his resurrection, now and forever. Prayers of Intercession and Illumination Hymn: “Let All Mortal Flesh Keep Silence,” verses 1-3 Hymn continued on the next page. Scripture Reading: John 18.1-14 ~ Jesus’ Arrest and Betrayal Hymn: “Meekness and Majesty” ~ Lif Up Your Hearts 157, verses 1-3 Verse 1: Verse 2: Meekness and majesty, manhood and Deity Father's pure radiance, perfect in innocence, in perfect harmony, the Man who is God. yet learns obedience to death on a cross, Lord of eternity dwells in humanity, suffering to give us life, conquering through sacrifice, kneels in humility, and washes our feet. and, as they crucify, prays, “Father forgive.” Chorus: Chorus Oh, what a mystery—meekness and majesty; bow down and worship, for this is your God. -

Gifts from David P. Becker Is Supported by the Stevens

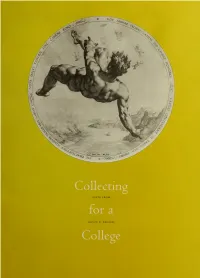

CoUectin' GIFTS FROM for DAVID P. BECKER College CoUectin GIFTS FROM for a DAVID P. BECKER Coll Essay by Marjorie B. Cohn Catalogue by David P. Becker BowDOiN College Museum of A Brunswick, Maine 1995 This catalogue accompanies an exhibition of the same name at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art from April 20 through [une 4. 1995. Cover Cat. no. 20. Hcndrik Goltzius, The Four Disgncers, I 588, after Cornells Cornclisz. van Haarlem Frontispieci; Cat. no. 5. Albrecht Diircr. 5/. Michael Fighting the Dragon, ca. 1497, from tlu- Apocalypse Design hv Michael Mahan Graphics, Baih. M.unc Photographs by Dennis Griggs. Tannery Hill Studios, Topsham. Maine Printing hv IViinior Luiiogr.iplu-i>, Lewiston. Maine ISBN: 0-916606-28-7 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 95-75252 Copyright © 1995 b\- the President and Trustees of Bowdoin College All rights reserved NOTES All works arc executed on white or off-white colored paper, unless specified otherwise. Measurements are height before width. For woodcuts and lithographs, measurements arc of the image area; for etchings and engravings, the plate; and for drawings, the sheet—unless specified otherwise. Works are listed chronologically in the order of the execution of the print, Oeuvre catalogues for an artist's prints are cited in the headings directly under the medium and measurements; the heading "References" contains notices of the specific impressions in this collection. BCMA is Bowdoin College Museum of Art. Bowdoin's accession numbers (in parentheses at the end of the provenance) indicate the year of the gift. t indicates works that are illustrated m this catalogue. -

I. English-Dutch

agent Intaglio Printmaking © Jasmien Roelens 2007 & CvT UGent I. ENGLISH-DUTCH brush etching Vakgebied: diepdruktechnieken UDC: 762.02 Project: (Diepdruktechnieken JR) Werkcode: JR 9 Begrip: tonale diepdruktechniek waarbij plaatselijk met zuur op de plaat geschilderd wordt Nl-term: penseelets En-term: brush etching, lavis <Beeld> ((Griffiths, A A.) 92)2) NL penseelets Trefwoord: penseelets Flexie: plu agent Vakgebied: diepdruktechnieken UDC: 762.02 Project: penseeletsen Extrainfo: <Extrasyn>gravure au lavisis Boven: (Diepdruktechnieken JR) (tonale diepdruktechniek) Werkcode: JR16 Neven: (open bijt) , (diepets) , (blinddruk) NL etsmiddel Onder: (spit bite) Definitie: Dergelijke effecten [gestructureerde toon] kunnen ook plaatselijk bereikt worden door met zuur op de plaat te American roulette Vakgebied: diepdruktechnieken schilderen. Dit wordt wel penseelets of gravure au lavis UDC: 762.02 Project: (Diepdruktechnieken JR) genoemd. Gedeelten in de prent die open, of met het penseel Werkcode: JR17 geëtst zijn, zullen aan de kanten een heel karakteristieke rand NL moulette vertonen door opeenhoping van inkt bij de niveauverschillen in de plaat. ((Gascoigne, B.) 18c) Commentaar: De penseelets was een voorloper van de applying resin by hand Vakgebied: aquatinttechniek, meer bepaald van spit bite. diepdruktechnieken UDC: 762.02 Project: Contexten: Met een sterk zuur of met etswater dat met bijv. (Diepdruktechnieken JR) Arabische gom of honing verdikt is, kan op de plaat Werkcode: JR18 ‘geschilderd’ worden, om bijv. aquatinten plaatselijk te -

Fifty Short Sermons by T

FIFTY SHORT SERMONS BY T. De WITT TALMAGE COMPILED BY HIS DAUGHTER MAY TALMAGE NEW ^SP YORK GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY TUB NBW YO«K PUBUC LIBRARY O t. COPYRIGHT, 1923, BY GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY 1EW YO:;iC rUbLiC LIBRMIY ASTOR, LENOX AND TILDEN FOUNDATIONS R 1025 L FIFTY SHORT SERMONS BY T. DE WITT TALMAGE. II PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA y CONTENTS I The Three Crosses II Twelve Entrances . III Jordanic Passage . IV The Coming Sermon V Cloaks for Sin /VI The Echoes . VII A Dart through the Liver VIII The Monarch of Books . JX The World Versus the Soul ^ X The Divine Surgeon XI Music in Worship . XII A Tale Told, or, The Passing Years XIII What Were You Made For? XIV Pulpit and Press . XV Hard Rowing . XVI NoontiGe of Life . XVII Scroll oi Heroes XVIII Is Life Worth Living? , XIX Grandmothers , ,. j.,^' XX The Capstoii^''''' '?'*'''' XXI On Trial .... XXII Good Qame Wasted XXIII The Sensitiveness of Christ XXIV Arousing Considerations Ti CONTENTS PAGE XXV The Threefold Glory of the Church . 155 XXVI Living Life Over Again 160 XXVII Meanness of Infidelity 163 XXVIII Magnetism of Christ 168 XXIX The Hornet's Mission 176 XXX Spicery of Religion 182 XXXI The House on the Hills 188 XXXII A Dead Lion 191 XXXIII The Number Seven 196 XXXIV Distribution of Spoils 203 XXXV The Sundial of Ahaz 206 XXXVI The Wonders of the Hand . .210 XXXVII The Spirit of Encouragement . .218 XXXVIII The Ballot-Box 223 XXXIX Do Nations Die? 229 XL The Lame Take the Prey . -

Rembrandt's Three Crosses

Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum Spotlight Series: October 2008 By Paul Crenshaw, assistant curator for prints and drawings and senior lecturer in art history One of the most dynamic prints ever made, Rembrandt van Rijn’s The Three Crosses (1653) displays technical innovation and engagement with the human subjectivity of Rembrandt van Rijn The Three Crosses, 1653 Drypoint (4th state), 15 1/4 x 17 13/16" Christ’s death. A torrential downpour of lines Gift of Dr. Malvern B. Clopton, 1930 envelopes dozens of figures on the hill of Rembrandt van Rijn Golgotha, where Christ is pictured crucified The Three Crosses, 1660-61 Etching and drypoint (4th state)tate) amidst the two thieves. Even though it is an 15 1/4 x 17 13/16 " Gift of Dr. Malvern B. Clopton, 1930 inherently tragic subject commonly portrayed in Christian tradition, never before had it been staged with such sweeping emotional force. Rembrandt was inspired by the text of the Gospels (Matthew 27:45–54) proclaiming that a darkness covered the land from noon to three o’clock, when Jesus cried out with a loud voice, “Elí, Elí, lemá sabachtháni?” (“My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”). When Jesus died, the passage continues, the earth shook, rocks split, tombs opened, and the bodies of many sleeping saints arose. To achieve these supernatural effects, Rembrandt employed the kind of bold technical ingenuity that helped define him as one of the most significant printmakers of his age. The Kemper Art Museum impression is a fine example of the fourth state of the print, which gives a dramatically different tenor and narrative focus to his subject than earlier states did. -

Rembrandt's 1654 Life of Christ Prints

REMBRANDT’S 1654 LIFE OF CHRIST PRINTS: GRAPHIC CHIAROSCURO, THE NORTHERN PRINT TRADITION, AND THE QUESTION OF SERIES by CATHERINE BAILEY WATKINS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Adviser: Dr. Catherine B. Scallen Department of Art History CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2011 ii This dissertation is dedicated with love to my children, Peter and Beatrice. iii Table of Contents List of Images v Acknowledgements xii Abstract xv Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Historiography 13 Chapter 2: Rembrandt’s Graphic Chiaroscuro and the Northern Print Tradition 65 Chapter 3: Rembrandt’s Graphic Chiaroscuro and Seventeenth-Century Dutch Interest in Tone 92 Chapter 4: The Presentation in the Temple, Descent from the Cross by Torchlight, Entombment, and Christ at Emmaus and Rembrandt’s Techniques for Producing Chiaroscuro 115 Chapter 5: Technique and Meaning in the Presentation in the Temple, Descent from the Cross by Torchlight, Entombment, and Christ at Emmaus 140 Chapter 6: The Question of Series 155 Conclusion 170 Appendix: Images 177 Bibliography 288 iv List of Images Figure 1 Rembrandt, The Presentation in the Temple, c. 1654 178 Chicago, The Art Institute of Chicago, 1950.1508 Figure 2 Rembrandt, Descent from the Cross by Torchlight, 1654 179 Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, P474 Figure 3 Rembrandt, Entombment, c. 1654 180 The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1992.5 Figure 4 Rembrandt, Christ at Emmaus, 1654 181 The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1922.280 Figure 5 Rembrandt, Entombment, c. 1654 182 The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1992.4 Figure 6 Rembrandt, Christ at Emmaus, 1654 183 London, The British Museum, 1973,U.1088 Figure 7 Albrecht Dürer, St. -

Decision Tree Branch for Foolscap with Five-Pointed Collar Fall 2015

Are roundels in a pyramid form Decision Tree Branch for (2 below, 1 on top) or pointing - Second collar point & down (2 on top, 1 below) ball fully extend beyond front chain line — ► [lab, lac}- Front chain line Foolscap with Five-Pointed Collar *) bisects second collar on top ball from front Fall 2015 (pyramid) Are the peaks divided (stripes in cap)? YES n/a Ea, Eb, F, Q, H, J. K, L M. N. Q, S A, B. C. D. 0 . U in------------- --------------- FIG. 1 Decision branch diagram for Foolscap with Five-Pointed Collar watermark, developed by Louisa Smieska and Alison McCann, Fall 2015 Decision Trees and Fruitful Collaborations The Watermark Identification in Rembrandt’s Etchings (WIRE) Project at Cornell Andrew C. Weislogel with C. Richard Johnson, Jr., and contributions from students1 Any additions to the file of It is no exaggeration to say that Rembrandt’s etchings count among the most compelling examples of artistic watermarks that has been production in the history of Western culture. The many compiled will not only catalogues of the artist's prints compiled since 1751- describing multiple states, ordering works by subject improve our understanding of matter or by date, distinguishing his work from that of his pupils, and identifying copies and posthumous impressions Rembrandts progress on his —attest to the enduring fascination with Rembrandt’s plates, but will enable us to technical experimentation and his versatility in interpreting the human psyche and capturing the natural world. Not test and refine the conclusions surprisingly, the complexity and artistic creativity of these prints continue to inspire scholarly research, technical reached so far.2—Erik Hinterding investigation, and multidisciplinary teaching approaches. -

Renaissance and Baroque Prints: Investigating the Collection September 8, 2017–January 8, 2018

Educator’s Guide Renaissance and Baroque Prints: Investigating the Collection September 8, 2017–January 8, 2018 ABOUT THIS GUIDE This guide is designed as a multidisciplinary companion for high school educators bringing their students to view Renaissance and Baroque Prints, on view at the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum from September 8, 2017, to January 8, 2018. Our intent is to offer a range of learning objectives, gallery discussions, and post-visit suggestions to stimulate the learning process, encourage dialogue, and help make meaning of the art presented. Teachers should glean from this guide what is most relevant and useful to their students. ABOUT THE EXHIBITION Renaissance and Baroque Prints surveys the Kemper Art Museum’s substantial holdings of European prints from the late fifteenth to eighteenth centuries. Printmaking during the Renaissance and Baroque eras served a wide variety of purposes. As part of the Renaissance in Italy and Northern Europe, artists developed sophisticated techniques and explored various themes that elevated the print to an important art form in its own right. In the Baroque era printmaking continued to flourish as artists experimented with new techniques and dramatic expressive effects. Exhibition highlights include work by major innovators of printmaking such as Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) and Rembrandt van Rijn (1606– 1669). Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471–1528), Melencolia I, 1514. Engraving, 9 3/8 x INTERDISCIPLINARY CONNECTIONS 7 5/16". Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Washington University in St. Louis. Transfer from Olin Library, Washington University, 1977. Architecture, Art, Art History, Baroque History, European History, Mythology, Printmaking, Religious Studies, Renaissance History LEARNING OBJECTIVES Students will explore innovative printmakers and popular themes represented. -

Etchings of Rembrandt

HAROLD B. UEE LIBRAHY BRIGHAM YOUNG UHlVBRSiTY PROVO, UTAH Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Brigham Young University http://www.archive.org/details/etchingsofrenibraOOhind ETCHINGS OF REMBRANDT THE GREAT ETCHERS 7^,J4« ^^ ETCHINGS OF REMBRANDT LONDON.GEORGE NEWNES LIMITED SOUTHAMPTON STREET. STRANDw.c. NEW YORK CHARLES SCRIBNEKS SONS TiiK Hai.i.antynk Pur.ss 'lAViSTorK St., Lonuon THE LIBRARY BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY PROVO, UTAH LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS PLATE REMBRANDT DRAWING AT A WINDOW, 1648 (Frontispiece) REMBRANDT'S FATHER, (?) 1630 i REMBRANDT'S MOTHER, 1628 11 iii REMBRANDT WEARING A SOFT CAP (1631) . REMBRANDT IN A CAP, LAUGHING, 1630 . iv REMBRANDT'S MOTHER, 1631 v REMBRANDT'S MOTHER SEATED AT A TABLE (1631) . vi REMBRANDT WEARING A SOFT HAT, 1631 ... vii CHRIST DISPUTING WITH THE DOCTORS (1630) . viii THE BLIND FIDDLER, 163 1 ix THE RAISING OF LAZARUS (1632) x THE RAT-KILLER, 1632 xi THE PAN-CAKE WOMAN, 1635 xii THE QUACKSALVER, 1635 xiii REMBRANDT AND HIS WIFE SASKIA, 1636 . xiv REMBRANDT'S WIFE SASKIA, 1634 xv THREE HEADS OF WOMEN (1637) xvi A YOUNG MAN IN A VELVET CAP, 1637 . xvii THE RETURN OF THE PRODIGAL SON, 1636 . xviii THE DEATH OF THE VIRGIN, 1639 . xix DEATH APPEARING TO A WEDDED COUPLE, 1639 . xx THE SICK WOMAN (1642) xxi JAN UYTENBOGAERT, 1635 xxii REMBRANDT LEANING ON A STONE SILL, 1639 . xxiii CORNELIS CLAESZ ANSLO, 1641 xxiv JAN ASSELYN (1647) xxv JAN SIX, 1647 XXVI THE RAISING OF LAZARUS : THE SMALLER PLATE, 1642 ........... XXVII THE HOG, 1643 XXVIII THE THREE TREES, 1643 xxix THE OMVAL, 1 645 xxx SIX'S BRIDGE, 1645 XXXI CHRIST CARRIED TO THE TOMB, 164c ... -

December 2.Pdf

DACQ December 2007 Packet 2: Dynasty Academic Competition Tossups Questions © 2007 Dynasty Academic Competition Questions. All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced or redistributed, in whole or in part, without express prior written permission solely by DACQ. Please note that non-authorized distribution of DACQ materials that involves no monetary exchange is in violation of this copyright. For permission, contact Chris Ray at [email protected]. 1. One of this work’s greatest villains is Korhior, who claims that forgiveness is impossible and incites Amlici and Nehor to rebellion, which is put down by the father of Shiblon and Helamon, Alma. The Testimony of Witnesses is added as a forward to this work, whose third section centers on Jacob, brother of (*) Nephi. Supposedly transcribed from Golden Plates as per the instructions of Moroni, FTP, identify this collection of scripture created by Joseph Smith, the primary text of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. ANSWER: The Book of Mormon 2. Alaric’s sack of this city may have created the Tsakonian language, while its more incompetent rulers included Archidamus IV, who failed to prevent an Antigonid invasion, and Cleomenes III, who was crushed at Sellasia by the Achean League. Nabis was the first to construct (*) walls around this city, which had relied on the code of Lycurgus, a social system based on the helot slave class, and a legendary martial culture for defense. FTP, identify this rival of Athens, a city on the Peloponnesus that sent three hundred warriors under Leonidas to the Battle of Thermopylae. -

Techniques of Printmaking

Techniques of printmaking. BLOCK PRINTING WOOD CUT Woodblock printing, known as xylography today, was the first method of printing applied to a paper medium. It became widely used throughout East Asia both as a method for printing on textiles and later, under the influence of Buddhism, on paper. As a method of printing on cloth, the earliest surviving examples from China date to about 220. Ukiyo-e is the best known type of Japanese woodblock art print. Most European uses of the technique on paper are covered by the term woodcut, except for the block-books produced mainly in the fifteenth century. Book illustration of the Durer, Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse Hortus Sanitatis lapidary c1496 Woodcut. Technique Woodcut is a relief printing technique in printmaking. An artist carves an image into the surface of a block of wood—typically with gouges—leaving the printing parts level with the surface while removing the non-printing parts. Areas that the artist cuts away carry no ink, while characters or images at surface level carry the ink to produce the print. The block is cut along the wood grain (unlike wood engraving, where the block is cut in the end-grain). The surface is covered with ink by rolling over the surface with an ink-covered roller (brayer), leaving ink upon the flat surface but not in the non-printing areas. Flat bed Printer. For colour printing, multiple blocks are used, each for one colour, although overprinting two colours may produce further colours on the print. Multiple colours can be printed by keying the paper to a frame around the woodblocks.