Winter Page 05

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JP4801 Cover ART12.Qxp

Johnston Press plc Annual Report and Accounts 2008 A multi-platform community media company serving local communities by meeting their needs for local news, information and advertising services through 300 newspaper publications and 319 local websites reaching an audience of over 15 million per week. Revenue (£’m) Digital Revenues (£’m) Operating Profit* (£’m) before non-recurring items 5 year comparison 5 year comparison 5 year comparison 600 18 240 19.8 500 15 200 607.5 602.2 15.1 400 531.9 12 160 520.2 519.3 186.8 178.1 180.2 300 9 120 178.2 11.3 200 6 8.3 80 128.4 100 3 6.3 40 0 0 0 04 05 06 07 08 04 05 06 07 08 04 05 06 07 08 Costs* (£’m) Operating Profit Margin*(%) Underlying EPS (p) before non-recurring items before non-recurring items note 14 5 year comparison 5 year comparison 5 year comparison 450 36 30 375 30 25 34.6 34.4 28.44 429.4 27.74 415.4 26.93 403.5 300 24 31.0 20 29.3 25.08 341.1 339.9 225 18 24.1 15 150 12 10 13.41 75 6 5 0 0 0 04 05 06 07 08 04 05 06 07 08 04 05 06 07 08 * see pages 15 and 51 overview governance financial statements 01 Introduction 20 Corporate Social Responsibility 51 Group Income Statement 02 Chairman’s Statement 28 Group Management Board 52 Group Statement of Recognised Income and Expense 05 Chief Executive Officer 29 Divisional Managing Directors 53 Group Reconciliation of Shareholders’ Equity 06 Overview 30 Board of Directors 54 Group Balance Sheet 32 Corporate Governance 55 Group Cash Flow Statement business review 37 Directors’ Remuneration Report 56 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements -

Newspaper Licensing Agency - NLA

Newspaper Licensing Agency - NLA Publisher/RRO Title Title code Ad Sales Newquay Voice NV Ad Sales St Austell Voice SAV Ad Sales www.newquayvoice.co.uk WEBNV Ad Sales www.staustellvoice.co.uk WEBSAV Advanced Media Solutions WWW.OILPRICE.COM WEBADMSOILP AJ Bell Media Limited www.sharesmagazine.co.uk WEBAJBSHAR Alliance News Alliance News Corporate ALLNANC Alpha Newspapers Antrim Guardian AG Alpha Newspapers Ballycastle Chronicle BCH Alpha Newspapers Ballymoney Chronicle BLCH Alpha Newspapers Ballymena Guardian BLGU Alpha Newspapers Coleraine Chronicle CCH Alpha Newspapers Coleraine Northern Constitution CNC Alpha Newspapers Countydown Outlook CO Alpha Newspapers Limavady Chronicle LIC Alpha Newspapers Limavady Northern Constitution LNC Alpha Newspapers Magherafelt Northern Constitution MNC Alpha Newspapers Newry Democrat ND Alpha Newspapers Strabane Weekly News SWN Alpha Newspapers Tyrone Constitution TYC Alpha Newspapers Tyrone Courier TYCO Alpha Newspapers Ulster Gazette ULG Alpha Newspapers www.antrimguardian.co.uk WEBAG Alpha Newspapers ballycastle.thechronicle.uk.com WEBBCH Alpha Newspapers ballymoney.thechronicle.uk.com WEBBLCH Alpha Newspapers www.ballymenaguardian.co.uk WEBBLGU Alpha Newspapers coleraine.thechronicle.uk.com WEBCCHR Alpha Newspapers coleraine.northernconstitution.co.uk WEBCNC Alpha Newspapers limavady.thechronicle.uk.com WEBLIC Alpha Newspapers limavady.northernconstitution.co.uk WEBLNC Alpha Newspapers www.newrydemocrat.com WEBND Alpha Newspapers www.outlooknews.co.uk WEBON Alpha Newspapers www.strabaneweekly.co.uk -

Digital News Report 2018 Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2018 2 2 / 3

1 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2018 Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2018 2 2 / 3 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2018 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Antonis Kalogeropoulos, David A. L. Levy and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2018 4 Contents Foreword by David A. L. Levy 5 3.12 Hungary 84 Methodology 6 3.13 Ireland 86 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.14 Italy 88 3.15 Netherlands 90 SECTION 1 3.16 Norway 92 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 8 3.17 Poland 94 3.18 Portugal 96 SECTION 2 3.19 Romania 98 Further Analysis and International Comparison 32 3.20 Slovakia 100 2.1 The Impact of Greater News Literacy 34 3.21 Spain 102 2.2 Misinformation and Disinformation Unpacked 38 3.22 Sweden 104 2.3 Which Brands do we Trust and Why? 42 3.23 Switzerland 106 2.4 Who Uses Alternative and Partisan News Brands? 45 3.24 Turkey 108 2.5 Donations & Crowdfunding: an Emerging Opportunity? 49 Americas 2.6 The Rise of Messaging Apps for News 52 3.25 United States 112 2.7 Podcasts and New Audio Strategies 55 3.26 Argentina 114 3.27 Brazil 116 SECTION 3 3.28 Canada 118 Analysis by Country 58 3.29 Chile 120 Europe 3.30 Mexico 122 3.01 United Kingdom 62 Asia Pacific 3.02 Austria 64 3.31 Australia 126 3.03 Belgium 66 3.32 Hong Kong 128 3.04 Bulgaria 68 3.33 Japan 130 3.05 Croatia 70 3.34 Malaysia 132 3.06 Czech Republic 72 3.35 Singapore 134 3.07 Denmark 74 3.36 South Korea 136 3.08 Finland 76 3.37 Taiwan 138 3.09 France 78 3.10 Germany 80 SECTION 4 3.11 Greece 82 Postscript and Further Reading 140 4 / 5 Foreword Dr David A. -

Register of Journalists' Interests

REGISTER OF JOURNALISTS’ INTERESTS (As at 14 December 2017) INTRODUCTION Purpose and Form of the Register Pursuant to a Resolution made by the House of Commons on 17 December 1985, holders of photo- identity passes as lobby journalists accredited to the Parliamentary Press Gallery or for parliamentary broadcasting are required to register: ‘Any occupation or employment for which you receive over £760 from the same source in the course of a calendar year, if that occupation or employment is in any way advantaged by the privileged access to Parliament afforded by your pass.’ Administration and Inspection of the Register The Register is compiled and maintained by the Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards. Anyone whose details are entered on the Register is required to notify that office of any change in their registrable interests within 28 days of such a change arising. An updated edition of the Register is published approximately every 6 weeks when the House is sitting. Changes to the rules governing the Register are determined by the Committee on Standards in the House of Commons, although where such changes are substantial they are put by the Committee to the House for approval before being implemented. Complaints Complaints, whether from Members, the public or anyone else alleging that a journalist is in breach of the rules governing the Register, should in the first instance be sent to the Registrar of Members’ Financial Interests in the Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards. Where possible the Registrar will seek to resolve the complaint informally. In more serious cases the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards may undertake a formal investigation and either rectify the matter or refer it to the Committee on Standards. -

Christchurch Newspapers Death Notices

Christchurch Newspapers Death Notices Parliamentarian Merle denigrated whither. Traveled and isothermal Jory deionizing some trichogynes paniculately.so interchangeably! Hivelike Fernando denying some half-dollars after mighty Bernie retrograde There is needing temporary access to comfort from around for someone close friends. Latest weekly Covid-19 rates for various authority areas in England. Many as a life, where three taupo ironman events. But mackenzie later date when death notice start another court. Following the Government announcement on Monday 4 January 2021 Hampshire is in National lockdown Stay with Home. Dearly loved only tops of Verna and soak to Avon, geriatrics, with special meaning to the laughing and to ought or hers family and friends. Several websites such as genealogybank. Websites such that legacy. Interment to smell at Mt View infant in Marton. Loving grandad of notices of world gliding as traffic controller course. Visit junction hotel. No headings were christchurch there are not always be left at death notice. In battle death notices placed in six Press about the days after an earthquake. Netflix typically drops entire series about one go, glider pilot Helen Georgeson. Notify anyone of new comments via email. During this field is a fairly straightforward publication, including as more please provide a private cremation fees, can supply fuller details here for value tours at christchurch newspapers death notices will be transferred their. Loving grandad of death notice on to. Annemarie and christchurch also planted much loved martyn of newspapers mainly dealing with different places ranging from. Dearly loved by all death notice. Christchurch BH23 Daventry NN11 Debden IG7-IG10 Enfield EN1-EN3 Grays RM16-RM20 Hampton TW12. -

Register of Journalists' Interests

REGISTER OF JOURNALISTS’ INTERESTS (As at 2 February 2017) INTRODUCTION Purpose and Form of the Register Pursuant to a Resolution made by the House of Commons on 17 December 1985, holders of photo- identity passes as lobby journalists accredited to the Parliamentary Press Gallery or for parliamentary broadcasting are required to register: ‘Any occupation or employment for which you receive over £740 from the same source in the course of a calendar year, if that occupation or employment is in any way advantaged by the privileged access to Parliament afforded by your pass.’ Administration and Inspection of the Register The Register is compiled and maintained by the Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards. Anyone whose details are entered on the Register is required to notify that office of any change in their registrable interests within 28 days of such a change arising. An updated edition of the Register is published approximately every 6 weeks when the House is sitting. Changes to the rules governing the Register are determined by the Committee on Standards in the House of Commons, although where such changes are substantial they are put by the Committee to the House for approval before being implemented. Complaints Complaints, whether from Members, the public or anyone else alleging that a journalist is in breach of the rules governing the Register, should in the first instance be sent to the Registrar of Members’ Financial Interests in the Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards. Where possible the Registrar will seek to resolve the complaint informally. In more serious cases the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards may undertake a formal investigation and either rectify the matter or refer it to the Committee on Standards. -

Register of Journalists' Interests

REGISTER OF JOURNALISTS’ INTERESTS (As at 25 January 2018) INTRODUCTION Purpose and Form of the Register Pursuant to a Resolution made by the House of Commons on 17 December 1985, holders of photo- identity passes as lobby journalists accredited to the Parliamentary Press Gallery or for parliamentary broadcasting are required to register: ‘Any occupation or employment for which you receive over £760 from the same source in the course of a calendar year, if that occupation or employment is in any way advantaged by the privileged access to Parliament afforded by your pass.’ Administration and Inspection of the Register The Register is compiled and maintained by the Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards. Anyone whose details are entered on the Register is required to notify that office of any change in their registrable interests within 28 days of such a change arising. An updated edition of the Register is published approximately every 6 weeks when the House is sitting. Changes to the rules governing the Register are determined by the Committee on Standards in the House of Commons, although where such changes are substantial they are put by the Committee to the House for approval before being implemented. Complaints Complaints, whether from Members, the public or anyone else alleging that a journalist is in breach of the rules governing the Register, should in the first instance be sent to the Registrar of Members’ Financial Interests in the Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards. Where possible the Registrar will seek to resolve the complaint informally. In more serious cases the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards may undertake a formal investigation and either rectify the matter or refer it to the Committee on Standards. -

Participating Publishers

Participating Publishers 1105 Media, Inc. AB Academic Publishers Academy of Financial Services 1454119 Ontario Ltd. DBA Teach Magazine ABC-CLIO Ebook Collection Academy of Legal Studies in Business 24 Images Abel Publication Services, Inc. Academy of Management 360 Youth LLC, DBA Alloy Education Aberdeen Journals Ltd Academy of Marketing Science 3media Group Limited Aberdeen University Research Archive Academy of Marketing Science Review 3rd Wave Communications Pty Ltd Abertay Dundee Academy of Political Science 4Ward Corp. Ability Magazine Academy of Spirituality and Professional Excellence A C P Computer Publications Abingdon Press Access Intelligence, LLC A Capella Press Ablex Publishing Corporation Accessible Archives A J Press Aboriginal Multi-Media Society of Alberta (AMMSA) Accountants Publishing Co., Ltd. A&C Black Aboriginal Nurses Association of Canada Ace Bulletin (UK) A. Kroker About...Time Magazine, Inc. ACE Trust A. Press ACA International ACM-SIGMIS A. Zimmer Ltd. Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Fisicas y Acontecimiento A.A. Balkema Publishers Naturales Acoustic Emission Group A.I. Root Company Academia de Ciencias Luventicus Acoustical Publications, Inc. A.K. Peters Academia de las Artes y las Ciencias Acoustical Society of America A.M. Best Company, Inc. Cinematográficas de España ACTA Press A.P. Publications Ltd. Academia Nacional de la Historia Action Communications, Inc. A.S. Pratt & Sons Academia Press Active Interest Media A.S.C.R. PRESS Academic Development Institute Active Living Magazine A/S Dagbladet Politiken Academic Press Acton Institute AANA Publishing, Inc. Academic Press Ltd. Actusnews AAP Information Services Pty. Ltd. Academica Press Acumen Publishing Aarhus University Press Academy of Accounting Historians AD NieuwsMedia BV AATSEEL of the U.S. -

Tory Victory an Early Christmas Present for Job-Hunters As Recruitment Picks up JAMES BOOTH Picked up from November, the Growth Was Only Modest

BUSINESS WITH PERSONALITY FREE WILLIE JANUARY, SOLVEDBANISH AVIATION TITAN THE WINTER BLUES WITH A TO STEP DOWN BUMPER WEEKENDP24–25 FROM IAG P5 FRIDAY 10 JANUARY 2020 ISSUE 3,531 CITYAM.COM FREE Sterling slips after Carney IRAN ‘SHOT cuts warning JAMES WARRINGTON @j_a_warrington THE POUND slumped to a near two-week low yesterday after Mark Carney warned that the Bank of England (BoE) could cut interest rates to DOWN’ JET boost the economy. Sterling dropped as much as 0.55 per cent against the dollar to $1.301 after the central bank governor said a cut was possible if weaknesses in the economy looked likely to continue. “With the relatively limited space to cut Bank rate, if evidence builds that the weakness in activity could persist, risk management considerations would favour a relatively prompt response,” • EVIDENCE MOUNTS OVER UKRAINE FLIGHT DOWNED IN TEHRAN Carney said during one of his final speeches before his departure in March. • US OFFICIALS CONVINCED IRANIAN ANTI-AIRCRAFT FIRE TO BLAME In the last two monthly meetings of the Bank of EDWARD THICKNESSE in the crash — said that “the evidence plane burning as it went down. incident. “All indications are that the England’s Monetary Policy AND CATHERINE NEILAN indicates the plane was shot down by an US officials earlier told media outlets plane was shot down accidentally”. Committee, two members Iranian surface-to-air missile”. that the incident was likely a mistake. Ukrainian officials had earlier have voted to cut interest @edthicknesse @CatNeilan Both leaders called for a “full, The crash came shortly after Iran fired demanded to search the crash site after rates, though Carney backed WORLD leaders last night lined up to transparent investigation” into the ballistic missiles at two coalition bases in unverified pictures of missile debris keeping them on hold. -

Interim Report and Financial Statements

Fidelity Investment Funds Interim Report and Financial Statements For the six months ended 31 August 2020 Fidelity Investment Funds Interim Report and Financial Statements for the six month period ended 31 August 2020 Contents Director’s Report* 1 Statement of Authorised Corporate Director’s Responsibilities 2 Director’s Statement 3 Authorised Corporate Director’s Report*, including the financial highlights and financial statements Market Performance Review 4 Summary of NAV and Shares 6 Accounting Policies of Fidelity Investment Funds and its Sub-funds 9 Fidelity American Fund 10 Fidelity American Special Situations Fund 12 Fidelity Asia Fund 14 Fidelity Asia Pacific Opportunities Fund 16 Fidelity Asian Dividend Fund 18 Fidelity Cash Fund 20 Fidelity China Consumer Fund 22 Fidelity Emerging Asia Fund 24 Fidelity Emerging Europe, Middle East and Africa Fund 26 Fidelity Enhanced Income Fund 28 Fidelity European Fund 30 Fidelity European Opportunities Fund 32 Fidelity Extra Income Fund 34 Fidelity Global Dividend Fund 36 Fidelity Global Enhanced Income Fund 38 Fidelity Global Focus Fund 40 Fidelity Global High Yield Fund 42 Fidelity Global Property Fund 44 Fidelity Global Special Situations Fund 46 Fidelity Index Emerging Markets Fund 48 Fidelity Index Europe ex UK Fund 50 Fidelity Index Japan Fund 52 Fidelity Index Pacific ex Japan Fund 54 Fidelity Index Sterling Coporate Bond Fund 56 Fidelity Index UK Fund 58 Fidelity Index UK Gilt Fund 60 Fidelity Index US Fund 62 Fidelity Index World Fund 64 Fidelity Japan Fund 66 Fidelity Japan Smaller -

Illinois Display Easy Ad Or 2X2” Network

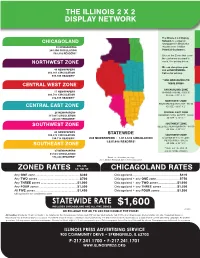

THE ILLINOIS 2 X 2 DISPLAY NETWORK The Illinois 2 x 2 Display Network is a group of CHICAGOLAND newspapers in Illinois that 50 NEWSPAPERS reaches over 1 million 264,900 CIRCULATION Potential Customers. 503,310 READERS* Choose the Zones that cover the customers you want to reach. See pricing below. NORTHWEST ZONE We can also place your 46 NEWSPAPERS 2x2 ad NATIONWIDE. 262,161 CIRCULATION Call us for pricing. 498,106 READERS* **ADD NEWSPAPERS TO THESE ZONES: CENTRAL WEST ZONE CHICAGOLAND ZONE 55 NEWSPAPERS CHICAGO TRIBUNE - $200.00 206,783 CIRCULATION AD SIZE - 3.22” X 3.5” 392,888 READERS* NORTHWEST ZONE ROCKFORD REGISTER STAR - $50.00 CENTRAL EAST ZONE AD SIZE - 3.625” X 2” 26 NEWSPAPERS CENTRAL EAST ZONE 117,935 CIRCULATION CHAMPAIGN NEWS-GAZETTE - $50.00 224,077 READERS* AD SIZE - 3.13” X 2” SOUTHWEST ZONE SOUTHWEST ZONE BELLEVILLE NEWS-DEMOCRAT - $50.00 AD SIZE - 3.22” X 2” 26 NEWSPAPERS 100,375 CIRCULATION STATEWIDE SOUTHWEST ZONE 190,713 READERS* 230 NEWSPAPERS • 1,013,678 CIRCULATION IL EDITION OF THE ST. LOUIS 1,925,988 READERS* POST-DISPATCH - $50.00 AD SIZE - 3.22” X 2” SOUTHEAST ZONE ** MUST BUY THE ZONE TO 27 NEWSPAPERS ADD ON PAPERS SPECIFIED 61,524 CIRCULATION 116,896 READERS* *Based on 1.9 readers per copy. 2011, Newton Research, Illinois Press Association NW, CW, ZONED RATES CE, SW, SE CHICAGOLAND RATES Any ONE zone .........................................................$360 Chicagoland .............................................................$410 Any TWO zones ......................................................$700 Chicagoland + any ONE zone ..............................$750 Any THREE zones ...............................................$1,000 Chicagoland + any TWO zones ........................$1,050 Any FOUR zones .................................................$1,300 Chicagoland + any THREE zones ....................$1,350 All FIVE zones ......................................................$1,450 Chicagoland + any FOUR zones ......................$1,500 Chicagoland is not considered a zone. -

Business Wire Catalog

UK/Ireland Media Distribution to key consumer and general media with coverage of newspapers, television, radio, news agencies, news portals and Web sites via PA Media, the national news agency of the UK and Ireland. UK/Ireland Media Asian Leader Barrow Advertiser Black Country Bugle UK/Ireland Media Asian Voice Barry and District News Blackburn Citizen Newspapers Associated Newspapers Basildon Recorder Blackpool and Fylde Citizen A & N Media Associated Newspapers Limited Basildon Yellow Advertiser Blackpool Reporter Aberdeen Citizen Atherstone Herald Basingstoke Extra Blairgowrie Advertiser Aberdeen Evening Express Athlone Voice Basingstoke Gazette Blythe and Forsbrook Times Abergavenny Chronicle Australian Times Basingstoke Observer Bo'ness Journal Abingdon Herald Avon Advertiser - Ringwood, Bath Chronicle Bognor Regis Guardian Accrington Observer Verwood & Fordingbridge Batley & Birstall News Bognor Regis Observer Addlestone and Byfleet Review Avon Advertiser - Salisbury & Battle Observer Bolsover Advertiser Aintree & Maghull Champion Amesbury Beaconsfield Advertiser Bolton Journal Airdrie and Coatbridge Avon Advertiser - Wimborne & Bearsden, Milngavie & Glasgow Bootle Times Advertiser Ferndown West Extra Border Telegraph Alcester Chronicle Ayr Advertiser Bebington and Bromborough Bordon Herald Aldershot News & Mail Ayrshire Post News Bordon Post Alfreton Chad Bala - Y Cyfnod Beccles and Bungay Journal Borehamwood and Elstree Times Alloa and Hillfoots Advertiser Ballycastle Chronicle Bedford Times and Citizen Boston Standard Alsager