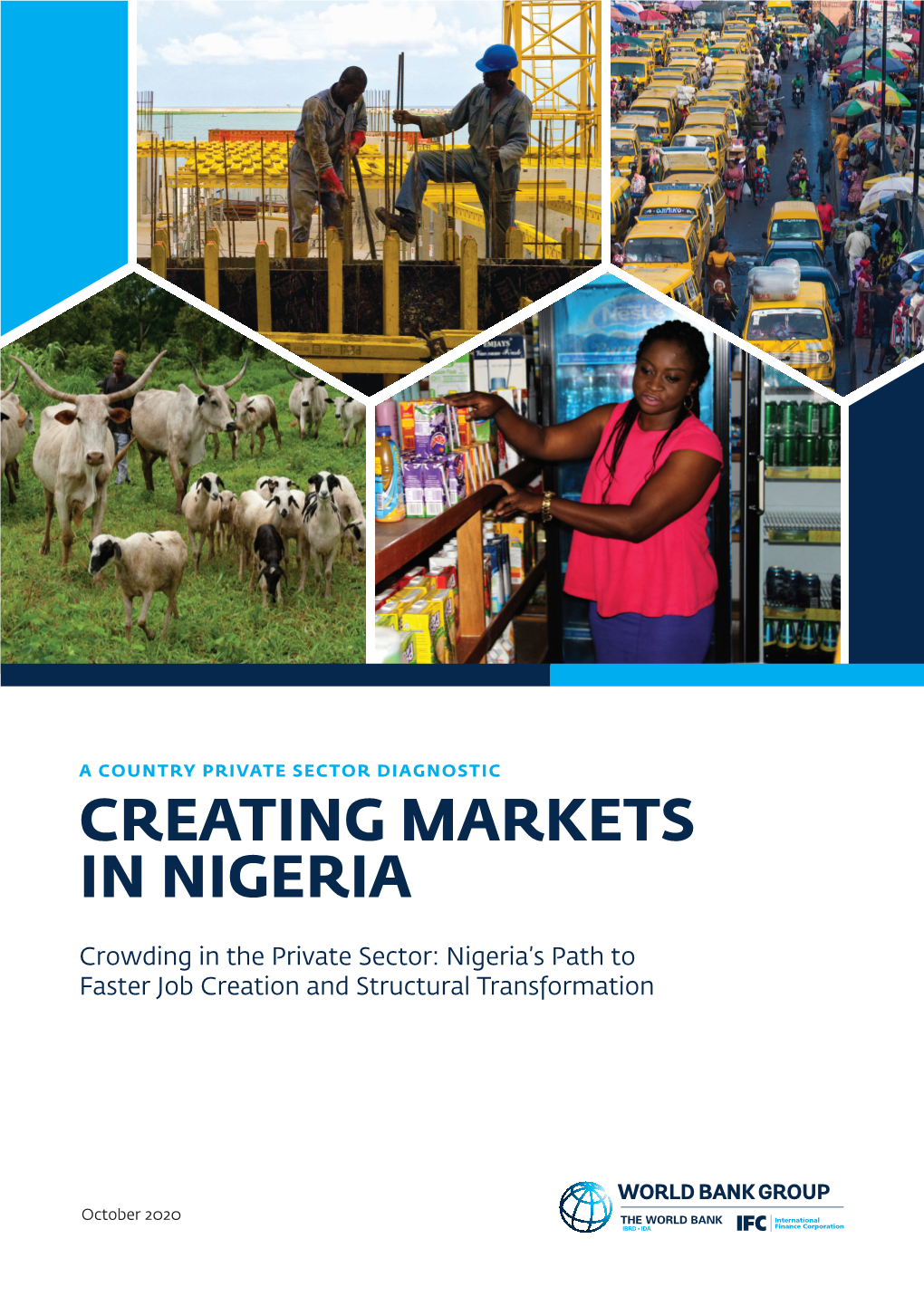

Creating Markets in Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urban Governance and Turning African Ciɵes Around: Lagos Case Study

Advancing research excellence for governance and public policy in Africa PASGR Working Paper 019 Urban Governance and Turning African CiƟes Around: Lagos Case Study Agunbiade, Elijah Muyiwa University of Lagos, Nigeria Olajide, Oluwafemi Ayodeji University of Lagos, Nigeria August, 2016 This report was produced in the context of a mul‐country study on the ‘Urban Governance and Turning African Cies Around ’, generously supported by the UK Department for Internaonal Development (DFID) through the Partnership for African Social and Governance Research (PASGR). The views herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those held by PASGR or DFID. Author contact informaƟon: Elijah Muyiwa Agunbiade University of Lagos, Nigeria [email protected] or [email protected] Suggested citaƟon: Agunbiade, E. M. and Olajide, O. A. (2016). Urban Governance and Turning African CiƟes Around: Lagos Case Study. Partnership for African Social and Governance Research Working Paper No. 019, Nairobi, Kenya. ©Partnership for African Social & Governance Research, 2016 Nairobi, Kenya [email protected] www.pasgr.org ISBN 978‐9966‐087‐15‐7 Table of Contents List of Figures ....................................................................................................................... ii List of Tables ........................................................................................................................ iii Acronyms ............................................................................................................................ -

Nigeria's Renewal: Delivering Inclusive Growth in Africa's Largest Economy

McKinsey Global Institute McKinsey Global Institute Nigeria’s renewal: Delivering renewal: Nigeria’s inclusive largest growth economy in Africa’s July 2014 Nigeria’s renewal: Delivering inclusive growth in Africa’s largest economy The McKinsey Global Institute The McKinsey Global Institute (MGI), the business and economics research arm of McKinsey & Company, was established in 1990 to develop a deeper understanding of the evolving global economy. Our goal is to provide leaders in the commercial, public, and social sectors with the facts and insights on which to base management and policy decisions. MGI research combines the disciplines of economics and management, employing the analytical tools of economics with the insights of business leaders. Our “micro-to-macro” methodology examines microeconomic industry trends to better understand the broad macroeconomic forces affecting business strategy and public policy. MGI’s in-depth reports have covered more than 20 countries and 30 industries. Current research focuses on six themes: productivity and growth; natural resources; labour markets; the evolution of global financial markets; the economic impact of technology and innovation; and urbanisation. Recent reports have assessed job creation, resource productivity, cities of the future, the economic impact of the Internet, and the future of manufacturing. MGI is led by three McKinsey & Company directors: Richard Dobbs, James Manyika, and Jonathan Woetzel. Michael Chui, Susan Lund, and Jaana Remes serve as MGI partners. Project teams are led by the MGI partners and a group of senior fellows, and include consultants from McKinsey & Company’s offices around the world. These teams draw on McKinsey & Company’s global network of partners and industry and management experts. -

Human Immunodeficiency and Hepatitis B Viral Co-Infection In

Available online at www.ijmrhs.com cal R edi ese M ar of c l h a & n r H u e o a J l l t h International Journal of Medical Research & a S n ISSN No: 2319-5886 o c i t i Health Sciences, 2020, 9(3): 8-17 e a n n c r e e t s n I • • IJ M R H S Human Immunodeficiency and Hepatitis B Viral Co-infection in Women Attending Antenatal Care Clinic in a Tertiary Health Institution in Nigeria Charles Njoku1,2, Anthony Umego2, Henry Okpara3 and Amarachukwu Njoku2 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Calabar, Nigeria 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Calabar Teaching Hospital, Calabar, Nigeria 3Department of Chemical Pathology, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Nnewi Campus, Anambra State, Nigeria *Corresponding e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Background: Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections are major global health problems with common modes of transmission. Objective: To determine the prevalence, demographic characteristics, risk factors and liver dysfunction among antenatal women with HIV and HBV co-infection. Methodology: A cross- sectional study of 586 pregnant women. Socio-demographic data were collected and blood samples were collected and tested for HBsAg and HIV infection. The liver function test was conducted on those who tested positive to HBV alone and have HIV/HBV co-infection. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 18 statistical program. Result: The prevalence of patients with HIV and HBV co-infection was 0.3%. They are single and in the age group of 21-24. -

Lebanon Crisis

LEBANON Lebanon Public Disclosure Authorized ECONOMIC Sinking MONITOR (To the Top 3) Public Disclosure Authorized Spring 2021 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Middle East and North Africa Region Lebanon Economic Monitor Lebanon Sinking (To the Top 3) لبنان يغرق )نحو أسوأ ثالث أزمات عاملية( Le Naufrage du Liban (Top 3 des pires crises mondiales) Spring 2021 Global Practice for Macroeconomics, Trade & Investment Middle East and North Africa Region 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 LEBANON ECONOMIC MONITOR Document of the World Bank The Deliberate Depression Fall 2020 Middle East and North Africa Region TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms . vii Preface . ix Executive Summary . xi xv . الموجز Résumé . xix 1 . The Policy Context . 1 2 . Recent Macro-Financial Developments . 3 Output and Demand . .3 Fiscal Developments...........................................................................4 The External Sector ............................................................................9 Money and Banking . .11 3 . Global Crises Comparators: Looking for the Minimum . 19 Per Capita Output ............................................................................21 Depreciation-Inflation . .22 Fiscal . .23 Debt ........................................................................................24 External Position . .24 Overall ......................................................................................25 4 . Outlook and Risks . .27 The FX Subsidy . .28 Large Scale Interruptions to Vital Public Services -

(AWS) AUDIT REPORT Nigerian Bottling Company Limited

ALLIANCE FOR WATER STEWARDSHIP (AWS) AUDIT REPORT Based on AWS Standard Version 1.0 Nigerian Bottling Company Limited (Member of Coca Cola Hellenic Group) #1 Lateef Jakande Road, Agidingbe Ikeja, Lagos State Nigeria. Report Date: 23-08-2019 Report Version: 02.0 Prepared by: Control Union Certification Services Accra, Ghana. Project No.: 867406AWS-2019-07 AWS Reference No.: AWS-010-INT-CU-00-05-00010-0072 Nigerian Bottling Company Limited AWS Audit Report Contents 1. General Information ............................................................................................................................. 3 1.1. Client Details ................................................................................................................................. 3 1.2. Certification Details ....................................................................................................................... 3 2. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................... 3 3. Scope of Assessment............................................................................................................................. 4 4. Description of the Catchment ............................................................................................................... 4 5. Summary on Stakeholder and shared Water Challenges ..................................................................... 7 6. Summary of the Assessment................................................................................................................ -

Customers Perception Approach in Nigeria

UNIVERSITY OF LAGOS DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION THE EFFECTIVENESS OF PRICING AS A MARKETING TOOL IN BANKS– CUSTOMERS PERCEPTION APPROACH IN NIGERIA. A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF POST GRADUATE STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF LAGOS, IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) IN BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION BY MBAH, CHRIS. CHUKWUEMEKA M.SC. MBA, B.SC. 25 JULY, 2012. 1 SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF LAGOS 2 CERTIFICATION This is to certify that the thesis THE EFFECTIVENESS OF PRICING AS A MARKETING TOOL IN BANKS– CUSTOMERS PERCEPTION APPROACH IN NIGERIA. Submitted to the School of Post Graduate Studies. University of Lagos For the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) Is a record of the original research carried out By MBAH, CHRIS. CHUKWUEMEKA In the Department of Business Administration ………………………………………… …………………………………. ………………….. NAME OF AUTHOR SIGNATURE DATE ………………………………………… …………………………………. ………………….. 1ST SUPERVISOR‟S NAME SIGNATURE DATE ………………………………………… …………………………………. ………………….. 2nd SUPERVISOR‟S NAME SIGNATURE DATE ………………………………………… …………………………………. ………………….. 1st INTERNAL EXAMINER SIGNATURE DATE ………………………………………… …………………………………. ………………….. 2nd INTERNAL EXAMINER SIGNATURE DATE ………………………………………… …………………………………. ………………….. 3 EXTERNAL EXAMINER SIGNATURE DATE ………………………………………… …………………………………. ………………….. SPGS REPRESENTATIVE SIGNATURE DATE DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my late parents who paid the initial price and laid the foundation for my education. May the Lord Almighty grant their souls eternal and blissful rest-Amen. 4 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The writing of a university thesis, especially at Ph.D level, is very demanding in terms of time, energy and other resources of the writer and some other persons. In this vein, I am greatly indebted to numerous authors whose work were cited, read and other persons who had time to read this work at various stages, especially my supervisors: Prof. -

World Population Ageing 2019

World Population Ageing 2019 Highlights ST/ESA/SER.A/430 Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division World Population Ageing 2019 Highlights United Nations New York, 2019 The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat is a vital interface between global policies in the economic, social and environmental spheres and national action. The Department works in three main interlinked areas: (i) it compiles, generates and analyses a wide range of economic, social and environmental data and information on which States Members of the United Nations draw to review common problems and take stock of policy options; (ii) it facilitates the negotiations of Member States in many intergovernmental bodies on joint courses of action to address ongoing or emerging global challenges; and (iii) it advises interested Governments on the ways and means of translating policy frameworks developed in United Nations conferences and summits into programmes at the country level and, through technical assistance, helps build national capacities. The Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs provides the international community with timely and accessible population data and analysis of population trends and development outcomes for all countries and areas of the world. To this end, the Division undertakes regular studies of population size and characteristics and of all three components of population change (fertility, mortality and migration). Founded in 1946, the Population Division provides substantive support on population and development issues to the United Nations General Assembly, the Economic and Social Council and the Commission on Population and Development. It also leads or participates in various interagency coordination mechanisms of the United Nations system. -

Challenges of Housing Delivery in Metropolitan Lagos

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Research on Humanities and Social Sciences www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1719 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2863 (Online) Vol.3, No.20, 2013 Challenges of Housing Delivery in Metropolitan Lagos Enisan Olugbenga, Ogundiran Adekemi (EnisanOlugbenga, Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria. [email protected] ) (OgundiranAdekemi, Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria. [email protected]) 1 ABSTRACT The need for adequate and decent housing is now part of the central focus and an integral component in National strategies for growth and poverty reduction. Decent and affordable housing is one of the basic needs of individuals, family and the community at large. As a pre-requisite to the survival of man, housing ranks second only to food. Housing as a unit of the environment has a profound influence on the health, efficient, social behaviour, satisfaction and general welfare of the community at large. It reflects the cultural, social and economic value of the society as it is the best physical and historical evidence of civilization in a country. The importance of housing in every life of human being and in national economy in general is enormous. Housing problem in Africa especially in Nigeria is not only limited to quantities but also qualities of the available housing units environment. It is in view of this that the paper views the challenges of housing delivery in the Lagos Metropolis. -

Assessment of Patronage of Tourist Sites in Badagry Local Government Area of Lagos State, Nigeria

Research on Humanities and Social Sciences www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-5766 (Paper) ISSN 2225-0484 (Online) Vol.10, No.12, 2020 Assessment of Patronage of Tourist Sites in Badagry Local Government Area of Lagos State, Nigeria Olugbemi, Moyosore Titilope 1 Awotide, Diran Olawale 2 Akinreti, Naimot Olayinka 1 Ogungbayi, Gafar Bolaji 1 Solana, Olorunfunmi, Isimioluwa 1 Bashorun, Oluwafeyikemi Edith 1 Akerele, Ezekiel Olaoluwa 2 1.Department of Home science and Hospitality Management 2.Department of Agricultural Economics and Farm Management Faculty of Agricultural Management and Rural Development, College of Agricultural Sciences, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ayetoro Campus, Ayetoro, Ogun State, Nigeria Abstract Poor patronage has been a subject of concern in hospitality industry and tourist attraction centres. This has impacted negatively on investment in the sector and overall economic development. The study therefore assessed patronage of tourist centres in Badagry Local Government area (LGA) of Lagos State. Nigeria. The study was based on primary data obtained in a cross-sectional survey of 240 respondents using multi-stage sampling technique in selected tourist centres in the LGA. The data collected were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Results revealed that majority of the respondents were between 26-30 years of age with an average of 36.2 years. Majority (62.1%) of the respondents were females, 71.1 percent were single and 41.7 percent had tertiary education. Furthermore, majority (60.8%) of the respondents had between 4-6 individuals as household members. The most visited tourist centre recreation purpose (62.1%), education purpose (87.1%), research purpose (84.2%), information purpose (72.1%) and sightseeing which accounted for 57.9%. -

2019-2020.Pdf

Interior of the School of Science and Technology ABOUT PAN-ATL>ANTIC WATCH VIDEO UNIVERSITY GOVERNANCE PAN-ATLANTIC UNIVERSITY SENATE BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF PAN-ATLANTIC The University Senate is the body responsible for the UNIVERSITY FOUNDATION organization and control of teaching in the University, approval of programme content, admission and discipline of students, and awarding of degrees. Pan-Atlantic University Foundation is the legal owner of the University. The Board of Trustees of the Foundation has the power to appoint the Vice-Chancellor and other members of Members of the Senate: the University Governing Council. 1. Prof. Juan Manuel Elegido- Vice-Chancellor and Chairman of Senate The following are the members of the Board of Trustees of the Foundation: 2. Prof. Chantal Epie 1. Mr Charles Osezua - O.O.N. (Chairman) 3. Prof. Enase Okonedo 2. Engr. Maurizio Fattarelli 4. Prof. Chris Ogbechie 3. Prof. Olusola Kushimo 5. Prof. Olayinka David-West 4. Prof. Stephen Afolami 6. Prof. Bright Eregha 5. Dr Imelda Wallace 7. Prof. Akintola Owolabi 6. Mrs Mary Agbomma Agbu 8. Prof. Olawale Ajai 7. Prof. Emmanuel Obikili 8. Dr Nkechi Asogwa 9. Prof. Onofowokan Oluyombo 10. Dr. Ikechukwu Obiaya PAN-ATLANTIC UNIVERSITY GOVERNING 11. Dr. Olusegun Vincent COUNCIL 12. Mr. Kingsley Ukoaha 13. Dr. Darlington Agholor The Governing Council is the highest body of the University, 14. Dr. Uchenna Uzo and it appoints the University's principal officers, deans and 15. Dr. Michael Okolo professors. Decisions of special importance for the long term future of the University have to be approved by the 16. Dr. -

Nigeria: Researched and Compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 13 May 2010

Nigeria: Researched and compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 13 May 2010 1. Please indicate what difficulties a child with autism or special needs as a result of an intellectual disability would encounter in nigeria: A. In accessing medical intervention or assistance from state authorities B. From the general community and family and in school 2. Would the parent (mother) of a child with autism or special needs as a result of an intellectual disability encounter any discrimination or difficulties in nigeria because of her child's condition? The United States Department of State report in March 2010 reviewing events of 2009 notes that for children there was: poor access to health care (United States Department of State, (11 March 2010), 2009 Human Rights Report: Nigeria, Section 6 Discrimination, Societal Abuses, and Trafficking in Persons, Children). This report also notes: Persons with disabilities faced social stigma, exploitation, and discrimination, and they were often regarded by their families as a source of shame. Many families viewed children with disabilities who could not contribute to family income as liabilities and sometimes severely abused or neglected them. Many indigent persons with disabilities begged on the streets (ibid, Section 6 Discrimination, Societal Abuses, and Trafficking in Persons, Persons with Disabilities). A report by the Nigerian state submitted to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child published in January 2010 states: Physically and emotionally challenged children have access to scholarship in some States as well as, free medical care, school bus, recreation facilities and book subsidies (UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, (5 January 2010), Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 44 of the Convention : Convention on the Rights of the Child : 3rd and 4th periodic report of States parties due in 2008 : Nigeria,p.88). -

Winning in Nigeria: Pharma's Next Frontier

Winning in Nigeria: Pharma’s next frontier Pharmaceuticals & Medical Products May 2017 Tania Holt Laura Millroy Matthews Mmopi Winning in Nigeria: Pharma’s next frontier Amid the country’s downturn, should companies still be looking here for growth? Yes—and we can learn five lessons from players getting it right today. Five years ago, Nigeria’s strong economic growth Putting growth in perspective sparked a burst of enthusiasm about opportunities As Africa’s largest economy and most highly in its pharmaceutical market. Yet capturing that populated country, Nigeria has been hailed as the promise has proved harder than expected, with next frontier for pharma, in the wake of industry many multinationals struggling to find a recipe for successes in South Africa and the growth hotspots success. More recently, the economic downturn has of Northern Africa. But the country’s recent slide cast an altogether different light on the industry’s into recession is prompting some companies to prospects. Given past challenges and today’s woes, take a step back and consider whether robust companies are starting to wonder whether Nigeria growth is still attainable. is ready for pharma—and even, as they reflect on their own experiences, whether pharma is ready In July 2016, the International Monetary Fund for Nigeria. cut Nigeria’s GDP growth forecast to –1.8 percent, the lowest since 1987, and a sharp fall from the We believe leaders should not be discouraged. 6 percent growth recorded between 2000 and Short-term shocks do not alter the fact that Nigeria 2014. Among the causes of this decline were the still offers attractive opportunities for companies global economic slowdown, the drop in crude oil with realistic expectations and carefully tailored prices, the dwindling of capital inflows, and the strategies.