The Arctic in World Affairs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pamphlet to Accompany Scientific Investigations Map 3131

Bedrock Geologic Map of the Seward Peninsula, Alaska, and Accompanying Conodont Data By Alison B. Till, Julie A. Dumoulin, Melanie B. Werdon, and Heather A. Bleick Pamphlet to accompany Scientific Investigations Map 3131 View of Salmon Lake and the eastern Kigluaik Mountains, central Seward Peninsula 2011 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................1 Sources of data ....................................................................................................................................1 Components of the map and accompanying materials .................................................................1 Geologic Summary ........................................................................................................................................1 Major geologic components ..............................................................................................................1 York terrane ..................................................................................................................................2 Grantley Harbor Fault Zone and contact between the York terrane and the Nome Complex ..........................................................................................................................3 Nome Complex ............................................................................................................................3 -

Preliminary Impact Assessment of the New Transport Infrastructure Project on Trans-Baikal Territory Geosystems, Russia

! Journal(of(Materials(and(( J. Mater. Environ. Sci., 2018, Volume 9, Issue 8, Page 2213-2224 Environmental(Sciences( ! ISSN(:(2028;2508( CODEN(:(JMESCN( http://www.jmaterenvironsci.com! Copyright(©(2018,((((((((((((((((((((((((((((( University(of(Mohammed(Premier(((((( (Oujda(Morocco( Preliminary impact assessment of the new transport infrastructure project on Trans-Baikal Territory geosystems, Russia N. Pomazkova 1*, L. Faleychik 1, A. Faleychik 2 1Institute of Natural Resources, Ecology and Cryology, Russian Academy of Sciences, Siberian Branch, Nedorezov street Chita, Russia. 2Transbaikal State University, Alexandro-Zavodskaya street, Chita, Russia. Received 04 Dec 2017, Abstract Revised 05 Feb 2018, Transbaikalia is in the interest area of the largest foreign policy initiative of China – the Accepted 10 Feb 2018 project “Silk Road Economic Belt”. The creation of the infrastructure linking member states (China, Russia, Mongolia) is one of the priority directions of this cooperation. First of all, the possibility of constructing a high-speed railway (HSR) is discussed. It is Keywords known that HSRs exert an overall positive effect on the development of regional !!environmental impact economies, especially on such brunches as tourism and regional cooperation. However assessment, this initiative carries risks for the natural ecosystems of the region such as: land take, !!Trans-Baikal Territory biodiversity loss, degradation and fragmentation of habitats, increasing pollution, barrier !!high-speed railway, effects, noise, land use impacts. This paper is focusing on the potential impacts of under !!spatial analysis, project on the geosystems. The spatial analysis results show that the project is likely to !!geographic information endanger 43 out of 122 natural geosystems located on the Trans-Baikal Territory. Along system (GIS), them there are 5 types of rare landscapes and 6 landscape types which are not presented !!nature protected areas. -

Belt and Road Transport Corridors: Barriers and Investments

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Belt and Road Transport Corridors: Barriers and Investments Lobyrev, Vitaly and Tikhomirov, Andrey and Tsukarev, Taras and Vinokurov, Evgeny Eurasian Development Bank, Institute of Economy and Transport Development 10 May 2018 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/86705/ MPRA Paper No. 86705, posted 18 May 2018 16:33 UTC BELT AND ROAD TRANSPORT CORRIDORS: BARRIERS AND INVESTMENTS Authors: Vitaly Lobyrev; Andrey Tikhomirov (Institute of Economy and Transport Development); Taras Tsukarev, PhD (Econ); Evgeny Vinokurov, PhD (Econ) (EDB Centre for Integration Studies). This report presents the results of an analysis of the impact that international freight traffic barriers have on logistics, transit potential, and development of transport corridors traversing EAEU member states. The authors of EDB Centre for Integration Studies Report No. 49 maintain that, if current railway freight rates and Chinese railway subsidies remain in place, by 2020 container traffic along the China-EAEU-EU axis may reach 250,000 FEU. At the same time, long-term freight traffic growth is restricted by a number of internal and external factors. The question is: What can be done to fully realise the existing trans-Eurasian transit potential? Removal of non-tariff and technical barriers is one of the key target areas. Restrictions discussed in this report include infrastructural (transport and logistical infrastructure), border/customs-related, and administrative/legal restrictions. The findings of a survey conducted among European consignors is a valuable source of information on these subjects. The authors present their recommendations regarding what can be done to remove the barriers that hamper international freight traffic along the China-EAEU-EU axis. -

The Importance of Protection 57 60 1

Arctic Ocean B e a u Utqiagvik f o r t Wrangel 4 (Point Barrow) S e a Island 62 49 52 3 61 1 2 Pacific Walrus Haulout 21. Dezhnev Bay 42. Tyulen’e Ozero Bay 58 The Importance of Protection 57 60 1. Cape Blossom 22. Anastasia Bay 43. Srednyaya Bay 56 59 23. Bogoslava Island 44. Somneniye Chukchi Sea 2. Somnitelnaya Spit 55 24. Cape Tiomney 45. Olutorskaya Spit The Walrus Islands State Game Sanctuary (WISGS) was established 51 3. Davidova Spit 54 25. Cape Sery-Anana 46. Lekalo Spit in 1960 to protect Pacific walrus haulout sites on seven small craggy 4. Gavai 39 53 5. Kolyuchyn Island 26. Verkhoturova Island 47. Cape Vankarem 47 27. Cape Golenishcheva 48. Cape Onmyn islands in northern Bristol Bay: Round Island, Summit Island, Crooked 48 6. Belyaka Spit 7. Strait of Neskenpil’gyn Lagoon 28. Cape Semionova 49. Ayon Island Island, High Island, Black Rock, and The Twins. Chukotka, Russia 5 7 30 50 29. Little Diomede Island 50. Cape Serdtse-Kamen’ t S o u 8. Unlisted 6 i e n u d a e b 30. Kotzebue Sound 51. Ryrkaipii r z t 9. Cape Inkigur 9 t 10 o The sanctuary includes the surrounding waters that support a diverse S K 31. King Island 52. Cape Shelagsky 10. Cape Dezhnev 16 12 11 group of marine mammals, seabirds, and other marine wildlife. 15 32. Gambell 53. Cape Lisburne g 29 11. Big Diomede Island 17 n Alaska, USA i 31 A b a r 33. Savoonga 54. -

Trans-Baykal (Rusya) Bölgesi'nin Coğrafyasi

International Journal of Geography and Geography Education (IGGE) To Cite This Article: Can, R. R. (2021). Geography of the Trans-Baykal (Russia) region. International Journal of Geography and Geography Education (IGGE), 43, 365-385. Submitted: October 07, 2020 Revised: November 01, 2020 Accepted: November 16, 2020 GEOGRAPHY OF THE TRANS-BAYKAL (RUSSIA) REGION Trans-Baykal (Rusya) Bölgesi’nin Coğrafyası Reyhan Rafet CAN1 Öz Zabaykalskiy Kray (Bölge) olarak isimlendirilen saha adını Rus kâşiflerin ilk kez 1640’ta karşılaştıkları Daur halkından alır. Rusçada Zabaykalye, Balkal Gölü’nün doğusu anlamına gelir. Trans-Baykal Bölgesi, Sibirya'nın en güneydoğusunda, doğu Trans-Baykal'ın neredeyse tüm bölgesini işgal eder. Bölge şiddetli iklim koşulları; birçok mineral ve hammadde kaynağı; ormanların ve tarım arazilerinin varlığı ile karakterize edilir. Rusya Federasyonu'nun Uzakdoğu Federal Bölgesi’nin bir parçası olan on bir kurucu kuruluşu arasında bölge, alan açısından altıncı, nüfus açısından dördüncü, bölgesel ürün üretimi açısından (GRP) altıncı sıradadır. Bölge topraklarından geçen Trans-Sibirya Demiryolu yalnızca Uzak Doğu ile Rusya'nın batı bölgeleri arasında bir ulaşım bağlantısı değil, aynı zamanda Avrasya geçişini sağlayan küresel altyapının da bir parçasıdır. Bölgenin üretim yapısında sanayi, tarım ve ulaşım yüksek bir paya sahiptir. Bu çalışmada Trans-Baykal Bölgesi’nin fiziki, beşeri ve ekonomik coğrafya özellikleri ele alınmıştır. Trans-Baykal Bölgesinin coğrafi özelliklerinin yanı sıra, ekonomik ve kültürel yapısını incelenmiştir. Bu kapsamda konu ile ilgili kurumsal raporlardan ve alan araştırmalarından yararlanılmıştır. Bu çalışma sonucunda 350 yıldan beri Rus gelenek, kültür ve yaşam tarzının devam ettiği, farklı etnik grupların toplumsal birliği sağladığı, yer altı kaynaklarının bölge ekonomisi için yüzyıllardır olduğu gibi günümüzde de önem arz ettiği, coğrafyasının halkın yaşam şeklini belirdiği sonucuna varılmıştır. -

EDB Eurasian Integration Yearbook 2011

Munich Personal RePEc Archive EDB Eurasian Integration Yearbook 2011 Vinokurov, Evgeny Euirasian Development Bank 2011 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/49178/ MPRA Paper No. 49178, posted 22 Aug 2013 07:48 UTC EDB EURASIAN I N T E G R A T I O N YEARBOOK 2011 Eurasian Integration Yearbook 2011 Annual publication of the Eurasian Development Bank УДК 339.7 ББК 65.012.3 Е 91 Eurasian Integration Yearbook 2011. – Almaty, 2011. – p. 352 ISBN 978–601–7151–21–8 Annual publication of the Eurasian Development Bank Edited by Evgeny Vinokurov The Eurasian Development Bank is an international financial institution established to promote economic growth and integration processes in Eurasia. The Bank was founded by the intergovernmental agreement signed in January 2006 by the Russian Federation and the Republic of Kazakhstan. In 2009–2010 Armenia, Tajikistan, Belarus became full members of the Bank. Electric power, water and energy, transportation infrastructure and high-tech and innovative industries are the key areas for Bank’s financing activity. As part of its mission the Bank carries out extensive research and analysis of contemporary development issues and trends in the region, with particular focus on Eurasian integration. The Bank also hosts regular conferences and round tables addressing various aspects of integration. In 2008, the Bank launched an annual EDB Eurasian Integration Yearbook (in English) and quarterly Journal of Eurasian Economic Integration (in Russian). Both publications are available online at: www.eabr.org. The Bank’s Strategy and Research Department publishes detailed Industry and Country Analytical Reports and plans to undertake a number of research projects. -

Social Transition in the North, Vol. 1, No. 4, May 1993

\ / ' . I, , Social Transition.in thb North ' \ / 1 \i 1 I '\ \ I /? ,- - \ I 1 . Volume 1, Number 4 \ I 1 1 I Ethnographic l$ummary: The Chuko tka Region J I / 1 , , ~lexdderI. Pika, Lydia P. Terentyeva and Dmitry D. ~dgo~avlensly Ethnographic Summary: The Chukotka Region Alexander I. Pika, Lydia P. Terentyeva and Dmitry D. Bogoyavlensky May, 1993 National Economic Forecasting Institute Russian Academy of Sciences Demography & Human Ecology Center Ethnic Demography Laboratory This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. DPP-9213l37. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recammendations expressed in this material are those of the author@) and do not ncccssarily reflect the vim of the National Science Foundation. THE CHUKOTKA REGION Table of Contents Page: I . Geography. History and Ethnography of Southeastern Chukotka ............... 1 I.A. Natural and Geographic Conditions ............................. 1 I.A.1.Climate ............................................ 1 I.A.2. Vegetation .........................................3 I.A.3.Fauna ............................................. 3 I1. Ethnohistorical Overview of the Region ................................ 4 IIA Chukchi-Russian Relations in the 17th Century .................... 9 1I.B. The Whaling Period and Increased American Influence in Chukotka ... 13 II.C. Soviets and Socialism in Chukotka ............................ 21 I11 . Traditional Culture and Social Organization of the Chukchis and Eskimos ..... 29 1II.A. Dwelling .............................................. -

ARCTIC GOVERNANCE: Understanding the Geopolitics Of

ARCTIC GOVERNANCE: Understanding the geopolitics of commercial shipping via the Northern Sea Route By HANS-PETTER BJØRKLI Master Thesis Department of Comparative Politics June 2015 Abstract The purpose of this study is to examine the implications of the development of the Northern Sea Route (NSR) with regard to governance in the Arctic. This topic is of importance as Arctic waters are getting bluer, more accessible, exploitable and attractive to investors, both public and private. Thus, numerous states and the international shipping industry are increasingly eyeing the NSR as an alternative trade route between Asia and Europe. However, the Arctic region and the NSR waters’ sovereignty remain unclear. Moreover, an increased density of international merchant vessels in the Arctic Ocean, a military reasserted Russia and the growing influence of China in international politics and trade suggest that the geopolitics of the Arctic may be challenged by the NSR. In this thesis, I have analysed the NSR’s effect on Arctic governance by applying classic theories of International Relations and illuminating the research question with data from expert interviews and a comprehensive document base. The findings indicate that liberalist values triumph realism, and that the NSR therefore does not have the potential to interrupt the current institutionalised and peaceful international political environment of the Arctic. Conversely, there is a possibility that conflicts in other parts of the world may disrupt the prosperity of international shipping via the NSR due to spillover effects. I Acknowledgements I owe my thanks to several people whom have provided me with guidance and motivation in the process of writing this thesis. -

Maritime Futures: the Arctic and the Bering Strait Region

COVER PHOTO SAMUEL JOHN NEELE NOVEMBER 2017 1616 Rhode Island Avenue NW Washington, DC 20036 202 887 0200 | www.csis.org Lanham • Boulder • New York • London 4501 Forbes Boulevard Lanham, MD 20706 301 459 3366 | www.rowman.com Maritime Futures The Arctic and the Bering Strait Region PRINCIPAL AUTHORS CONTRIBUTING AUTHOR Heather A. Conley Andreas Østhagen Matthew Melino ISBN 978-1-4422-8033-5 A Report of the Ë|xHSLEOCy280335z v*:+:!:+:! CSIS EUROPE PROGRAM Blank NOVEMBER 2017 Maritime Futures The Arctic and the Bering Strait Region PRINCIPAL AUTHORS CONTRIBUTING AUTHOR Heather A. Conley Andreas Østhagen Matthew Melino A REPORT OF THE CSIS EUROPE PROGRAM Lanham • Boulder • New York • London 594-71468_ch00_4P.indd 1 10/27/17 11:30 AM About CSIS For over 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has worked to develop solutions to the world’s greatest policy challenges. T oday, CSIS scholars are providing strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a nonprofit organ ization headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full- time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analy sis and develop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Founded at the height of the Cold War by David M. Abshire and Admiral Arleigh Burke, CSIS was dedicated to finding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. Since 1962, CSIS has become one of the world’s preeminent international institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global health and economic integration. -

The Russian-U.S. Borderland: Opportunities and Barriers, Desires and Fears

The Russian-U.S. Borderland: Opportunities and Barriers, Desires and Fears Serghei Golunov∗ Abstract The paper focuses on the Russia-U.S. cross-border area that lies in the Bering Sea region. Employing the concept of geographical proximity, I argue that the U.S.-Russian proximity works in a limited number of cases and for relatively few kinds of actors, such as companies supplying Chukotka with American goods, border guards conducting rescue operations, organizers of environmental projects and cruise tours, and aboriginal communities. The impressive territorial proximity between Asia and North America induces ambitious and sometimes widely advertised official and public desires of conquering the spatial divide, promoted by extreme travellers and planners of transcontinental tunnel or bridge projects. At the same time, cooperation is seriously hindered by limited economic potential of the Russian North-East, weakness of transportation networks, harsh climate, and pervasive alarmist sentiments on the Russian side of the border. Introduction Russian and U.S. territories are situated close to each other in the areas of the Bering Sea: the shortest distance between the closest islands across the border is less than four kilometers. However, the nearby territories are sparsely populated and have limited resources that make intensive cooperation between them problematic while larger cities are situated at a much larger distance across the border. The area where Russian and U.S. territories are close to each other can be conceptualized as a geographical proximity that is a multidimensional, relational, and highly subjective phenomenon. In what respects and for whom does the Russia-U.S. proximity matter? To what extent does it matter for cross-border cooperation? What kinds of desires does such proximity induce? Are there some pervasive alarmist sentiments linked with proximity and, if there are, what ways do they influence cross-border interaction? To respond to these questions, the following issues are addressed. -

Investigations of Belukha Whales in Coastal Waters

INVESTIGATIONS OF BELUKHA WHALES IN COASTAL WATERS OF WESTERN AND NORTHERN ALASKA I. DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND MOVEMENTS by Glenn A. Seaman, Kathryn J. Frost, and Lloyd F. Lowry Alaska Department of Fish and Game 1300 College Road Fairbanks, Alaska 99701 Final Report Outer Continental Shelf Environmental Assessment Program Research Unit 612 November 1986 153 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page LIST OF FIGURES . 157 LIST OF TABLES . 159 sumRY . 161 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . 162 WORLD DISTRIBUTION . 163 GENERAL 1 ISTRIBUTION IN ALASKA . 165 SEASONAL DISTRIBUTION IN ALASKA. 165 REGIONAL DISTRIBUTION AND ABUNDANCE. 173 Nor” h Aleutian Basin. 173 Saint Matthew-Hall Basin. s . 180 Saint George Basin. 184 Navarin Basin . 186 Norton Basin. 187 Hope Basin. 191 Barrow Arch . 196 Diapir Field. 205 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS . 208 LITERATURE CITED . 212 LIST OF PERSONAL COMMUNICANTS. 219 155 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1. Current world distribution of belukha whales, not including extralimital occurrences . Figure 2. Map of the Bering, Chuk&i, and Beaufort seas, showing major locations mentioned in text. Figure 3. Distribution of belukha whales in January and February . Figure 4. Distribution of belukha whales in March and April. Figure 5. Distribution of belukha whales in May and June . Figure 6. Distribution of belukha whales in July and August. Figure 7. Distribution of belukha whales in September and October. Figure 8. Distribution of belukha whales in November and Deeember. Figure 9. Map of the North Aleutian Basin showing locations mentioned in text. Figure 10. Map of the Saint Matthew-Hall Basin showing locations mentionedintext. Figure 11. Map of the Saint George and Navarin basins showing locations mentionedintext. -

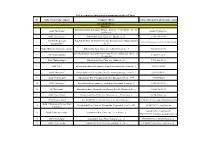

List of Exporters Interested in Supplying Grain to China

List of exporters interested in supplying grain to China № Name of exporting company Company address Contact Infromation (phone num. / email) Zabaykalsky Krai Rapeseed Zabaykalsky Krai, Kalgansky District, Bura 1st , Vitaly Kozlov str., 25 1 OOO ''Burinskoe'' [email protected]. building A 2 OOO ''Zelenyi List'' Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, Butina str., 93 8-914-469-64-44 AO "Breeding factory Zabaikalskiy Krai, Chernyshevskiy area, Komsomolskoe village, Oktober 3 [email protected] Тел.:89243788800 "Komsomolets" str. 30 4 OOO «Bukachachinsky Izvestyank» Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, Verkholenskaya str., 4 8(3022) 23-21-54 Zabaykalsky Krai, Alexandrovo-Zavodsky district,. Mankechur village, ul. 5 SZ "Mankechursky" 8(30240)4-62-41 Tsentralnaya 6 OOO "Zabaykalagro" Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, Gaidar str., 13 8-914-120-29-18 7 PSK ''Pole'' Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsky region, Novotsuruhaytuy, Lazo str., 1 8(30243)30111 8 OOO "Mysovaya" Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsky District, Novotsuruhaytuy, Lazo str., 1 8(30243)30111 9 OOO "Urulyungui" Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsky District, Dosatuy,Lenin str., 19 B 89245108820 10 OOO "Xin Jiang" Zabaykalsky Krai,Urban-type settlement Priargunsk, Lenin str., 2 8-914-504-53-38 11 PK "Baygulsky" Zabaykalsky Krai, Chernyshevsky District, Baygul, Shkolnaya str., 6 8(3026) 56-51-35 12 ООО "ForceExport" Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, Polzunova str. , 30 building, 7 8-924-388-67-74 13 ООО "Eсospectrum" Zabaykalsky Krai, Aginsky district, str. 30 let Pobedi, 11 8-914-461-28-74 [email protected] OOO "Chitinskaya