The George Wright Forum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Watkins Creek Ranch Gallatin MT Property Name County State

NPS Form 10-900a OMB No. 1024-0018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES CONTINUATION SHEET Section ___ Page __ SUPPLEMENTARY LISTING RECORD NRIS Reference Number: 06001180 Date Listed: 12/27/2006 Watkins Creek Ranch Gallatin MT Property Name County State N/A Multiple Name This property is listed in the National Register of Historic Places in accordance with the attached nomination documentation subject to the following exceptions, exclusions, or amendments, notwithstanding the National Park Service certification included in the nomination documentation. / Signatu^e/cof the Keeper Da&e 6f Action / U =====7I^== Amended Items in Nomination: Description: The correct Town, Range, Section notation in the first paragraph should read: Range 4 Easf. The sawed ends of the corner logs on the Isabel & Frederick Lincoln Cabin (Building #9) are not tapered, as they are on the similar Guest Duplex Cabins (#6-8), marking the slightly different form and details of the later cabin. These clarifications were confirmed with the MT SHPO office. DISTRIBUTION: National Register property file Nominating Authority (without nomination attachment) NFS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. Oct. 1990) National Park Service RECEIVED 2280 NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM 3 NAT PF<N MATIAMAI OADl/ irK'k/rJ-" uco iiniruiiriL i nilM OLIIVILC 1. Name of Property historic name: Watkins Creek Ranch other name/site number: Firehole Ranch 2. Location street & number: 1207 Firehole Ranch Road not for publication: n/a vicinity: n/a city/town: West Yellowstone state: Montana code: MT county: Gallatin code: 031 zip code: 59758 3. -

Forbidden Waters

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2013 Forbidden Waters Will Freihofer The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Freihofer, Will, "Forbidden Waters" (2013). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 459. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/459 This Professional Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FORBIDDEN WATERS By WILLIAM BREED FREIHOFER B.A., University of Montana, Missoula, MT, 2010 Professional Paper presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of M.A. in Environmental Science and Natural Resource Journalism The University of Montana Missoula, MT Official Graduation Date: May 2013 Approved by: Sandy Ross, Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School Lee Banville School of Journalism Jeremy Lurgio School of Journalism Bill Borrie College of Forestry and Conservation © COPYRIGHT William Breed Freihofer 2013 Forbidden Waters by Will Freihofer Since 1950, Yellowstone National Park has encompassed one of the largest river systems with a complete ban on boating in the world. Despite the prohibition, generations of kayakers have been unable to resist the world-class whitewater of the Black Canyon of the Yellowstone River, and today advocates on both sides of the issue press the Park Service to determine if visitors will ever legally wet a paddle on the thousands of miles of rivers and streams in the first National Park. -

WELLFIELD ·I I

"~), ~ ',0 )/)'./ iiJ G./) / .,' it-3~" - - ' REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MATSHENG AREA GROUNDWATER INVESTIGATION (TB 10/2/12/92-93) DRAFT TECHNICAL REPORT T9: SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPACT ASSESSMENT AUGUST 1995 Prepared by = ~.-~~.. INTER WELLFIELD ·i i,.. CO'ISULT in association with BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Keyworth, Nottingham, UK MATSHENG AREA GROUNDWATER INVESTIGATION Technical Report T9 August 1995 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Usable potable water supplies are limited to the Matsheng village areas. Economic fresh water supplies identified during recent groundwater investigations are located in village areas of Lokgwabe and Lehututu. Brackish water supplies identified outside the village areas are not available for use by livestock using communal grazing areas as they are either in areas already occupied or in areas with other land use designations. 2. No significant usable water supplies were identified in the communal grazing areas through the MAGI programme, and based on the available geophysical evidence, the chances of striking groundwater supplies for livestock in Matsheng communal areas are poor. 3. Total water consumption in the Matsheng area during the past year (to May 1995) is estimated at 254,200m' (697 m' per day). Of this amount about 150,000 m' (60%) are consumed by livestock watered at about 150 wells, boreholes and dams on pans. 4. Matsheng village households using public standpipes consume about 670 litres per household per week, or 20 litres per person per day (67% of the 30 litre DWA standard rate for rural village standpipe users). Residents of the four RAD settlements served by council bowsers received a ration of about 7 litres per person per day, or just 23% of the DWA standard. -

Botswana Environment Statistics Water Digest 2018

Botswana Environment Statistics Water Digest 2018 Private Bag 0024 Gaborone TOLL FREE NUMBER: 0800600200 Tel: ( +267) 367 1300 Fax: ( +267) 395 2201 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.statsbots.org.bw Published by STATISTICS BOTSWANA Private Bag 0024, Gaborone Phone: 3671300 Fax: 3952201 Email: [email protected] Website: www.statsbots.org.bw Contact Unit: Environment Statistics Unit Phone: 367 1300 ISBN: 978-99968-482-3-0 (e-book) Copyright © Statistics Botswana 2020 No part of this information shall be reproduced, stored in a Retrieval system, or even transmitted in any form or by any means, whether electronically, mechanically, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Statistics Botswana. BOTSWANA ENVIRONMENT STATISTICS WATER DIGEST 2018 Statistics Botswana PREFACE This is Statistics Botswana’s annual Botswana Environment Statistics: Water Digest. It is the first solely water statistics annual digest. This Digest will provide data for use by decision-makers in water management and development and provide tools for the monitoring of trends in water statistics. The indicators in this report cover data on dam levels, water production, billed water consumption, non-revenue water, and water supplied to mines. It is envisaged that coverage of indicators will be expanded as more data becomes available. International standards and guidelines were followed in the compilation of this report. The United Nations Framework for the Development of Environment Statistics (UNFDES) and the United Nations International Recommendations for Water Statistics were particularly useful guidelines. The data collected herein will feed into the UN System of Environmental Economic Accounting (SEEA) for water and hence facilitate an informed management of water resources. -

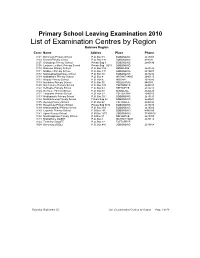

List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O

Primary School Leaving Examination 2010 List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O. Box 48 BOBONONG 2619207 0103 Borotsi Primary School P.O. Box 136 BOBONONG 819208 0107 Gobojango Primary School Private Bag 8 BOBONONG 2645436 0108 Lentswe-Le-Moriti Primary School Private Bag 0019 BOBONONG 0110 Mabolwe Primary School P.O. Box 182 SEMOLALE 2645422 0111 Madikwe Primary School P.O. Box 131 BOBONONG 2619221 0112 Mafetsakgang primary school P.O. Box 46 BOBONONG 2619232 0114 Mathathane Primary School P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0117 Mogapi Primary School P.O. Box 6 MOGAPI 2618545 0119 Molalatau Primary School P.O. Box 50 MOLALATAU 845374 0120 Moletemane Primary School P.O. Box 176 TSETSEBYE 2646035 0123 Sefhophe Primary School P.O. Box 41 SEFHOPHE 2618210 0124 Semolale Primary School P.O. Box 10 SEMOLALE 2645422 0131 Tsetsejwe Primary School P.O. Box 33 TSETSEJWE 2646103 0133 Modisaotsile Primary School P.O. Box 591 BOBONONG 2619123 0134 Motlhabaneng Primary School Private Bag 20 BOBONONG 2645541 0135 Busang Primary School P.O. Box 47 TSETSEBJE 2646144 0138 Rasetimela Primary School Private Bag 0014 BOBONONG 2619485 0139 Mabumahibidu Primary School P.O. Box 168 BOBONONG 2619040 0140 Lepokole Primary School P O Box 148 BOBONONG 4900035 0141 Agosi Primary School P O Box 1673 BOBONONG 71868614 0142 Motsholapheko Primary School P O Box 37 SEFHOPHE 2618305 0143 Mathathane DOSET P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0144 Tsetsebye DOSET P.O. Box 33 TSETSEBYE 3024 Bobonong DOSET P.O. Box 483 BOBONONG 2619164 Saturday, September 25, List of Examination Centres by Region Page 1 of 39 Boteti Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0201 Adult Education Private Bag 1 ORAPA 0202 Baipidi Primary School P.O. -

General Management Plan, Sagamore

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior GENERAL MANAGEMENT PLAN 2008 o TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 DEDICATION 2 SUPERINTENDENT’S NOTE 3 BACKGROUND 7 THE PARK 21 FOUNDATION FOR PLANNING 27 THE PLAN 29 OVERVIEW 31 MANAGING THE PARK’S RESOURCES 40 PROVIDING A POSITIVE VISITOR EXPERIENCE 48 IMPROVING PARK OPERATIONS AND PARTNERSHIPS 52 PROJECTED COSTS 52 NEXT STEPS 53 APPENDICES 55 A: RECORD OF DECISIONS 64 B: PARK LEGISLATION 66 C: MANAGEMENT ZONING 69 D: SECTION 106 COMPLIANCE 71 E: LIST OF PREPARERS 2 o DEDICATION THE SAGAMORE HILL NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE GENERAL MANAGEMENT PLAN IS DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF DR. JOHN ALLEN GABLE. DR. GABLE SERVED AS THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF THE THEODORE ROOSEVELT ASSOCIATION (TRA) FROM 1974 UNTIL HIS DEATH IN FEBRUARY 2005. DURING HIS TENURE WITH THE TRA, DR. GABLE WAS DEEPLY INVOLVED WITH THE MANAGEMENT AND OPERATION OF SAGAMORE HILL AND WAS ACTIVELY ENGAGED IN THE PARK’S PLANNING PROCESS AT THE TIME OF HIS DEATH. WE APPRECIATED HIS CANDOR AND HIS WIT, HIS INTELLECT AND HIS COMMITMENT TO EXCELLENCE IN CONSIDERING THE FUTURE OF SAGAMORE HILL. 1 o NOTE FROM THE SUPERINTENDENT LTHOUGH I CAME TO SAGAMORE HILL LATE IN THE PROCESS OF DEVELOPING THE GENERAL MANAGEMENT PLAN, I WOULD LIKE TO EXPRESS MY SUPPORT FOR THE DIRECTION AND TONE THAT A IT SETS FOR THE COMING DECADES. THE PRIMARY AIM OF THIS PLAN IS TO ENHANCE THE OVERALL VISITOR EXPERIENCE AND MAKE IT EASIER FOR THE PUBLIC TO UNDERSTAND, APPRECIATE, AND KNOW SAGAMORE HILL AS THE ROOSEVELTS THEMSELVES WOULD HAVE KNOWN IT WHILE THEY LIVED HERE. -

Local Communities, Cbos/Trusts, and People–Park Relationships: a Case Study of the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, Botswana

Local Communities, CBOs/Trusts, and People–Park Relationships: A Case Study of the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, Botswana Naomi Moswete and Brijesh Thapa Introduction The concept of community-based natural resources management (CBNRM) was introduced in Botswana in the early 1990s, and was premised on the idea that rural people must have the power to make decisions regarding utilization of natural resources (Mulale et al. 2013). CBNRM was built on the need for local participation and involvement in the management and utilization of protected areas, as well as community empowerment within and adjacent to them (Thakadu 2006; Mutandwa and Gadzirayi 2007). Based on these fundamental tenets, the CBNRM initiative was designed to alleviate poverty, advance conservation, strengthen rural economies, and empower communities to manage and derive equitable benefits from resources, as well as determine their long-term use (Arntzen et al. 2003; GoB 2007). Since its adoption, the implementation arm for CBNRM initiatives has been largely orchestrated through the formation and operation of a local community-based organization (CBO) and/or community trust (Moswete et al. 2009; Mbaiwa 2013). This local organizational entity (here- after referred to as a CBO/Trust) has evolved as an instrumental tool for rural communities as it provides a forum for them to negotiate their interests, problems, goals, and aspirations in a democratic and participatory process (Rozemeijer 2001; Arntzen et al. 2003; Mbaiwa 2013). This paper examines how local residents assess CBOs/Trusts, and people–park relation- ships, within the context of the Botswana portion of the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park (KTP). CBNRM in Botswana In Botswana, park-based tourism and/or community ecotourism is strongly linked to the notion of CBNRM (GoB 2007). -

Botswana Semiology Research Centre Project Seismic Stations In

BOTSWANA SEISMOLOGICAL NETWORK ( BSN) STATIONS 19°0'0"E 20°0'0"E 21°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 23°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 25°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 27°0'0"E 28°0'0"E 29°0'0"E 30°0'0"E 1 S 7 " ° 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° " 7 S 1 KSANE Kasane ! !Kazungula Kasane Forest ReserveLeshomo 1 S Ngoma Bridge ! 8 " ! ° 0 0 ' # !Mabele * . MasuzweSatau ! ! ' 0 ! ! Litaba 0 ° Liamb!ezi Xamshiko Musukub!ili Ivuvwe " 8 ! ! ! !Seriba Kasane Forest Reserve Extension S 1 !Shishikola Siabisso ! ! Ka!taba Safari Camp ! Kachikau ! ! ! ! ! ! Chobe Forest Reserve ! !! ! Karee ! ! ! ! ! Safari Camp Dibejam!a ! ! !! ! ! ! ! X!!AUD! M Kazuma Forest Reserve ! ShongoshongoDugamchaRwelyeHau!xa Marunga Xhauga Safari Camp ! !SLIND Chobe National Park ! Kudixama Diniva Xumoxu Xanekwa Savute ! Mah!orameno! ! ! ! Safari Camp ! Maikaelelo Foreset Reserve Do!betsha ! ! Dibebe Tjiponga Ncamaser!e Hamandozi ! Quecha ! Duma BTLPN ! #Kwiima XanekobaSepupa Khw!a CHOBE DISTRICT *! !! ! Manga !! Mampi ! ! ! Kangara # ! * Gunitsuga!Njova Wazemi ! ! G!unitsuga ! Wazemi !Seronga! !Kaborothoa ! 1 S Sibuyu Forest Reserve 9 " Njou # ° 0 * ! 0 ' !Nxaunxau Esha 12 ' 0 Zara ! ! 0 ° ! ! ! " 9 ! S 1 ! Mababe Quru!be ! ! Esha 1GMARE Xorotsaa ! Gumare ! ! Thale CheracherahaQNGWA ! ! GcangwaKaruwe Danega ! ! Gqose ! DobeQabi *# ! ! ! ! Bate !Mahito Qubi !Mahopa ! Nokaneng # ! Mochabana Shukumukwa * ! ! Nxabe NGAMILAND DISTRICT Sorob!e ! XurueeHabu Sakapane Nxai National Nark !! ! Sepako Caecae 2 ! ! S 0 " Konde Ncwima ° 0 ! MAUN 0 ' ! ! ' 0 Ntabi Tshokatshaa ! 0 ° ! " 0 PHDHD Maposa Mmanxotai S Kaore ! ! Maitengwe 2 ! Tsau Segoro -

Hoover Digest

HOOVER DIGEST RESEARCH + OPINION ON PUBLIC POLICY WINTER 2019 NO. 1 THE HOOVER INSTITUTION • STANFORD UNIVERSITY The Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace was established at Stanford University in 1919 by Herbert Hoover, a member of Stanford’s pioneer graduating class of 1895 and the thirty-first president of the United States. Created as a library and repository of documents, the Institution approaches its centennial with a dual identity: an active public policy research center and an internationally recognized library and archives. The Institution’s overarching goals are to: » Understand the causes and consequences of economic, political, and social change » Analyze the effects of government actions and public policies » Use reasoned argument and intellectual rigor to generate ideas that nurture the formation of public policy and benefit society Herbert Hoover’s 1959 statement to the Board of Trustees of Stanford University continues to guide and define the Institution’s mission in the twenty-first century: This Institution supports the Constitution of the United States, its Bill of Rights, and its method of representative government. Both our social and economic sys- tems are based on private enterprise, from which springs initiative and ingenuity. Ours is a system where the Federal Government should undertake no govern- mental, social, or economic action, except where local government, or the people, cannot undertake it for themselves. The overall mission of this Institution is, from its records, to recall the voice of experience against the making of war, and by the study of these records and their publication to recall man’s endeavors to make and preserve peace, and to sustain for America the safeguards of the American way of life. -

2009 Primary Directory

2009 PRIMARY SCHOOLS DIRECTORY WITH SOME STATISTICAL DATA No. Nane of sch Address Tel Fax Ownership Region Inspectoral Inspc Officer/Ccontact Regional Officer/Contact District council Roll Boys Roll Girls Total Ro Teachers Southern West- 1 Acacia Bag 2 Jwaneng 5884807 5881525 Private South Jwaneng Mr. Lethosa - Tel: 5802300 T. Mokwena, 5440722 Southern 177 187 364 31 Central 2 Adelaide Box 5151 Serowe 4635576 0 Private South Serowe South Mrs. Malefho - Tel: 4600553 G.B. Smile, 4631635 Central 144 175 319 16 Southern West- 3 Adult Edu. Centre Private South Jwaneng Mr. Lethosa - Tel: 5802302 T. Mokwena, 5440724 Southern 8 33 41 1 4 Aerodrome Box 718 F/Town 2404202 2404203 Council North F/Town S. Thabano - Tel: 2412266 Mrs. E. Maswikiti, 2415075 Francistown 396 389 785 27 Central 5 Agosi Box 1673 0 Council South Bobirwa Ms Elias - Tel: 2619335 G.B Smile, 4630626 Central 183 195 378 17 South 6 Al-Haq Box 1543 Molepolole 5920762 4633215 Private Central Kweneng C Tel: 5921305 Mack, 3972454 Kweneng 137 119 256 16 South 7 Al-Nur Box 78 Gaborone 3974974 3972905 Private Central Gabs North Mr. Thibelang - Tel: 3972454 K. Mack, 3972454 Gaborone 180 200 380 24 Mr. Mathumo - Tel: 8 Andrew Wellio Council West Maun Mr. B.K. Habana - 6865317 6865317 North West 299 279 578 17 South 9 Anne-Stine 5921127 Private Central Kweneng C Tel: 5921305 K. Mack, 3972455 Kweneng 15 11 26 3 South 10 Artesia Box 3 Artesia 5728225 0 Council Central Kgatleng West Ms. Mosweunyane - Tel: 5777226 K. Mack, 3972454 Kgatleng 204 200 404 16 Central GG Moepeng, 11 Baipidi Box 315 Maun 6868016 0 Council North Boteti Mr. -

DAILY HANSARD 23 November 2020

DAILY YOUR VOICE IN PARLIAMENT THETHE SECOND FIRST MEETING MEETING OF THE O FSECOND THE FIFTH SESSION SESSION OF OF THETHE ELEVEN TWELFTHT HPARLIAMENT PARLIAMENT MONDAY 23 NOVEMBER 2020 MIXED VERSION HANSARDHANSARD NO: NO. 200 193 DISCLAIMER Unocial Hansard This transcript of Parliamentary proceedings is an unocial version of the Hansard and may contain inaccuracies. It is hereby published for general purposes only. The nal edited version of the Hansard will be published when available and can be obtained from the Assistant Clerk (Editorial). THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SPEAKER The Hon. Phandu T. C. Skelemani PH, MP. DEPUTY SPEAKER The Hon. Mabuse M. Pule, MP. (Mochudi East) Clerk of the National Assembly - Ms B. N. Dithapo Deputy Clerk of the National Assembly - Mr L. T. Gaolaolwe Learned Parliamentary Counsel - Ms M. Mokgosi Assistant Clerk (E) - Mr R. Josiah CABINET His Excellency Dr M. E. K. Masisi, MP. - President His Honour S. Tsogwane, MP. (Boteti West) - Vice President Minister for Presidential Affairs, Governance and Public Hon. K. N. S. Morwaeng, MP. (Molepolole South) - Administration Hon. K. T. Mmusi, MP. (Gabane-Mmankgodi) - Minister of Defence, Justice and Security Hon. Dr L. Kwape, MP. (Kanye South) - Minister of International Affairs and Cooperation Hon. E. M. Molale, MP. (Goodhope-Mabule ) - Minister of Local Government and Rural Development Hon. K. S. Gare, MP. (Moshupa-Manyana) - Minister of Agricultural Development and Food Security Minister of Environment, Natural Resources Conservation Hon. P. K. Kereng, MP. (Specially Elected) - and Tourism Hon. Dr E. G. Dikoloti MP. (Mmathethe-Molapowabojang) - Minister of Health and Wellness Hon. T.M. Segokgo, MP. (Tlokweng) - Minister of Transport and Communications Hon. -

Geographical Names Standardization BOTSWANA GEOGRAPHICAL

SCALE 1 : 2 000 000 BOTSWANA GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES 20°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 28°0'0"E Kasane e ! ob Ch S Ngoma Bridge S " ! " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° Geographical Names ° ! 8 !( 8 1 ! 1 Parakarungu/ Kavimba ti Mbalakalungu ! ± n !( a Kakulwane Pan y K n Ga-Sekao/Kachikaubwe/Kachikabwe Standardization w e a L i/ n d d n o a y ba ! in m Shakawe Ngarange L ! zu ! !(Ghoha/Gcoha Gate we !(! Ng Samochema/Samochima Mpandamatenga/ This map highlights numerous places with Savute/Savuti Chobe National Park !(! Pandamatenga O Gudigwa te ! ! k Savu !( !( a ! v Nxamasere/Ncamasere a n a CHOBE DISTRICT more than one or varying names. The g Zweizwe Pan o an uiq !(! ag ! Sepupa/Sepopa Seronga M ! Savute Marsh Tsodilo !(! Gonutsuga/Gonitsuga scenario is influenced by human-centric Xau dum Nxauxau/Nxaunxau !(! ! Etsha 13 Jao! events based on governance or culture. achira Moan i e a h hw a k K g o n B Cakanaca/Xakanaka Mababe Ta ! u o N r o Moremi Wildlife Reserve Whether the place name is officially X a u ! G Gumare o d o l u OKAVANGO DELTA m m o e ! ti g Sankuyo o bestowed or adopted circumstantially, Qangwa g ! o !(! M Xaxaba/Cacaba B certain terminology in usage Nokaneng ! o r o Nxai National ! e Park n Shorobe a e k n will prevail within a society a Xaxa/Caecae/Xaixai m l e ! C u a n !( a d m a e a a b S c b K h i S " a " e a u T z 0 d ih n D 0 ' u ' m w NGAMILAND DISTRICT y ! Nxai Pan 0 m Tsokotshaa/Tsokatshaa 0 Gcwihabadu C T e Maun ° r ° h e ! 0 0 Ghwihaba/ ! a !( o 2 !( i ata Mmanxotae/Manxotae 2 g Botet N ! Gcwihaba e !( ! Nxharaga/Nxaraga !(! Maitengwe