Tight Bounds for Simon's Algorithm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Linear Cryptanalysis of Reduced-Round SIMON Using Super Rounds

cryptography Article Linear Cryptanalysis of Reduced-Round SIMON Using Super Rounds Reham Almukhlifi * and Poorvi L. Vora Department of Computer Science, The George Washington University, Washington, DC 20052, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 5 March 2020; Accepted: 15 March 2020; Published: 18 March 2020 Abstract: We present attacks on 21-rounds of SIMON 32/64, 21-rounds of SIMON 48/96, 25-rounds of SIMON 64/128, 35-rounds of SIMON 96/144 and 43-rounds of SIMON 128/256, often with direct recovery of the full master key without repeating the attack over multiple rounds. These attacks result from the observation that, after four rounds of encryption, one bit of the left half of the state of 32/64 SIMON depends on only 17 key bits (19 key bits for the other variants of SIMON). Further, linear cryptanalysis requires the guessing of only 16 bits, the size of a single round key of SIMON 32/64. We partition the key into smaller strings by focusing on one bit of state at a time, decreasing the cost of the exhaustive search of linear cryptanalysis to 16 bits at a time for SIMON 32/64. We also present other example linear cryptanalysis, experimentally verified on 8, 10 and 12 rounds for SIMON 32/64. Keywords: SIMON; linear cryptanalysis; super round 1. Introduction Lightweight cryptography is a rapidly growing area of research, emerging to fill the need for securing highly-constrained devices such as RFID tags and sensor networks. The limited hardware and software resources require that the cryptographic primitives be highly efficient. -

Giza and the Pyramids, Veteran Hosni Mubarak

An aeroplane flies over the pyramids and Sphinx on the Giza Plateau near Cairo. ARCHAEOLOGY The wonder of the pyramids Andrew Robinson enjoys a volume rounding up research on the complex at Giza, Egypt. n Giza and the Pyramids, veteran Hosni Mubarak. After AERAGRAM 16(2), 8–14; 2015), the tomb’s Egyptologists Mark Lehner and Zahi Mubarak fell from four sides, each a little more than 230 metres Hawass cite an Arab proverb: “Man power during the long, vary by at most just 18.3 centimetres. Ifears time, but time fears the pyramids.” It’s Arab Spring that year, Lehner and Hawass reject the idea that a reminder that the great Egyptian complex Hawass resigned, amid armies of Egyptian slaves constructed the on the Giza Plateau has endured for some controversy. pyramids, as the classical Greek historian four and a half millennia — the last monu- The Giza complex Herodotus suggested. They do, however, ment standing of that classical-era must-see invites speculation embrace the concept that the innovative list, the Seven Wonders of the World. and debate. Its three administrative and social organization Lehner and Hawass have produced an pyramids are the Giza and the demanded by the enormous task of build- astonishingly comprehensive study of the tombs of pharaohs Pyramids ing the complex were key factors in creating excavations and scientific investigations Khufu, Khafre and MARK LEHNER & ZAHI Egyptian civilization. CREATIVE GEOGRAPHIC L. STANFIELD/NATL JAMES that have, over two centuries, uncovered Menkaure, also known HAWASS The authors are also in accord over a the engineering techniques, religious and as Cheops, Chephren Thames & Hudson: theory regarding the purpose of the Giza cultural significance and other aspects of and Mycerinus, 2017. -

FPGA Modeling and Optimization of a SIMON Lightweight Block Cipher

sensors Article FPGA Modeling and Optimization of a SIMON Lightweight Block Cipher Sa’ed Abed 1,* , Reem Jaffal 1, Bassam Jamil Mohd 2 and Mohammad Alshayeji 1 1 Department of Computer Engineering, Kuwait University, Safat 13060, Kuwait; [email protected] (R.J.); [email protected] (M.A.) 2 Department of Computer Engineering, Hashemite University, Zarqa 13115, Jordan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +965-249-837-90 Received: 18 December 2018; Accepted: 18 February 2019; Published: 21 February 2019 Abstract: Security of sensitive data exchanged between devices is essential. Low-resource devices (LRDs), designed for constrained environments, are increasingly becoming ubiquitous. Lightweight block ciphers provide confidentiality for LRDs by balancing the required security with minimal resource overhead. SIMON is a lightweight block cipher targeted for hardware implementations. The objective of this research is to implement, optimize, and model SIMON cipher design for LRDs, with an emphasis on energy and power, which are critical metrics for LRDs. Various implementations use field-programmable gate array (FPGA) technology. Two types of design implementations are examined: scalar and pipelined. Results show that scalar implementations require 39% less resources and 45% less power consumption. The pipelined implementations demonstrate 12 times the throughput and consume 31% less energy. Moreover, the most energy-efficient and optimum design is a two-round pipelined implementation, which consumes 31% of the best scalar’s implementation energy. The scalar design that consumes the least energy is a four-round implementation. The scalar design that uses the least area and power is the one-round implementation. -

Lab 6: Simon Cipher Encryption EEL 4712 – Fall 2019

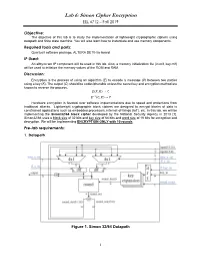

Lab 6: Simon Cipher Encryption EEL 4712 – Fall 2019 Objective: The objective of this lab is to study the implementation of lightweight cryptographic ciphers using datapath and finite state machine. You will also learn how to instantiate and use memory components. Required tools and parts: QuartusII software package, ALTERA DE10-lite board. IP Used: An altsyncram IP component will be used in this lab. Also, a memory initialization file (in.mif, key.mif) will be used to initialize the memory values of the ROM and RAM. Discussion: Encryption is the process of using an algorithm (E) to encode a message (P) between two parties using a key (K). The output (C) should be undecipherable unless the secret key and encryption method are known to reverse the process. 퐸(푃, 퐾) → 퐶 퐸−1(퐶, 퐾) → 푃 Hardware encryption is favored over software implementations due to speed and protections from traditional attacks. Lightweight cryptographic block ciphers are designed to encrypt blocks of data in constrained applications such as embedded processors, internet-of-things (IoT), etc. In this lab, we will be implementing the Simon32/64 block cipher developed by the National Security Agency in 2013 [1]. Simon32/64 uses a block size of 32 bits and key size of 64 bits and word size of 16 bits for encryption and decryption. We will be implementing ENCRYPTION ONLY with 10 rounds. Pre-lab requirements: 1. Datapath Figure 1. Simon 32/64 Datapath 1 Lab 6: Simon Cipher Encryption EEL 4712 – Fall 2019 The datapath and control signals (blue) for Simon32/64 block cipher are shown in Fig. -

Block Ciphers for the Iot – SIMON, SPECK, KATAN, LED, TEA, PRESENT, and SEA Compared

Block ciphers for the IoT { SIMON, SPECK, KATAN, LED, TEA, PRESENT, and SEA compared Michael Appel1, Andreas Bossert1, Steven Cooper1, Tobias Kußmaul1, Johannes L¨offler1, Christof Pauer1, and Alexander Wiesmaier1;2;3 1 TU Darmstadt 2 AGT International 3 Hochschule Darmstadt Abstract. In this paper we present 7 block cipher algorithms Simon, Speck, KATAN, LED, TEA, Present and Sea. Each of them gets a short introduction of their functions and it will be examined with regards to their security. We also compare these 7 block ciphers with each other and with the state of the art algorithm the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) to see how efficient and fast they are to be able to conclude what algorithm is the best for which specific application. Keywords: Internet of things (IoT); lightweight block ciphers; SIMON; SPECK; KATAN; LED; TEA; PRESENT; SEA 1 Introduction In modern IT The Internet of Things(IoT) is one of the most recent topics. Through the technical progress the internet has increasingly moving into our daily lives. More and more devices get functions to go online interconnect with each other and send and receive data. The increasingly smaller and cheaper expectant electronic control and communication components were installed in particular in recent years, increasingly in things of daily life. Typical fields of application are for example home automation, Security technology in the private or business environment as well as the supporting usage in the industry [1]. Be- cause of the very high price sensitivity in this environment the focus is set on the efficiency of the used programs and algorithms. -

SAL – a Lightweight Symmetric Cipher for Internet-Of-Things

International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering (IJITEE) ISSN: 2278-3075, Volume-8, Issue-11S, September 2019 SAL – A Lightweight Symmetric Cipher for Internet-of-Things Hemraj Shobharam Lamkuche, Dhanya Pramod, Vandana Onker, Shobharam Katiya, Geeta Lamkuche, Gurudevi Hiremath Abstract— The modern era of computing demands high-speed mathematical and engineering process of encoding source performance and maximizing efficiency for commercial information as plaintext into ciphertext by using a secret applications and business modules. Embedded systems and key of standard size. The scrambling of information can devices are unlike traditional computer systems. The computing be decrypted into original plaintext information by power of the embedded device is very limited to perform a specific task, it consumes little hardware footprint and operates at decrypting it using the same secret key used for the electronic high speed by minimizing clock cycles and memory encryption process (Stallings, 2010). The National management. Embedded security issues and security challenges Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has are a major concern resisting against advanced cryptanalytic approved lightweight cryptographic standards for attacks. In this research, we propose a new lightweight encryption algorithms specifically for low power- cryptographic algorithm SAL (Secure Advanced Lightweight). constrained devices (Kerry A. McKay, Larry Bassham, The algorithm is based on NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) standards and guidelines in design Meltem Sönmez Turan, 2017). The physical implementation of SAL to secure lower end of the device characteristics of lightweight block ciphers restricted up spectrum are internet of things (IoT), wireless sensors network to 1900 gate equivalents (GEs) and the performance (WSNs), aggregation network, pervasive devices, Radio characteristics of hardware implementation and software frequency identification (RFID) tags, and embedded devices. -

Improved Linear Cryptanalysis of Reduced-Round SIMON-32 and SIMON-48

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Software institutes' Online Digital Archive Improved Linear Cryptanalysis of reduced-round SIMON-32 and SIMON-48 Mohamed Ahmed Abdelraheem1 ?, Javad Alizadeh2??, Hoda A. Alkhzaimi3, Mohammad Reza Aref2, Nasour Bagheri4, and Praveen Gauravaram5 ??? 1 SICS Swedish ICT, Sweden, [email protected] 2 ISSL, E.E. Department, Sharif University of Technology, Iran, [email protected] 3 Section for Cryptology, DTU Compute, Technical University of Denmark, Denmark, [email protected] 4 E.E. Department of Shahid Rajaee Teachers Training University and the School of Computer Science of Institute for Research in Fundamental Sciences (IPM), Iran, [email protected] 5 Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia, [email protected] Abstract. In this paper we analyse two variants of SIMON family of light-weight block ciphers against linear cryptanalysis and present the best linear cryptanalytic results on these variants of reduced-round SIMON to date. We propose a time-memory trade-off method that finds differential/linear trails for any permu- tation allowing low Hamming weight differential/linear trails. Our method combines low Hamming weight trails found by the correlation matrix representing the target permutation with heavy Ham- ming weight trails found using a Mixed Integer Programming model representing the target differ- ential/linear trail. Our method enables us to find a 17-round linear approximation for SIMON-48 which is the best current linear approximation for SIMON-48. Using only the correlation matrix method, we are able to find a 14-round linear approximation for SIMON-32 which is also the current best linear approximation for SIMON-32. -

SIMON Says, Break the Area Records for Symmetric Key Block Ciphers on Fpgas

SIMON Says, Break the Area Records for Symmetric Key Block Ciphers on FPGAs Aydin Aysu, Ege Gulcan, and Patrick Schaumont Secure Embedded Systems Center for Embedded Systems for Critical Applications Bradley Department of ECE Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA 24061, USA faydinay,egulcan,[email protected] Abstract. While AES is extensively in use in a number of applications, its area cost limits its deployment in resource constrained platforms. In this paper, we have implemented SIMON, a recent promising low-cost alternative of AES on reconfigurable platforms. The Feistel network, the construction of the round function and the key generation of SIMON, enables bit-serial hardware architectures which can significantly reduce the cost. Moreover, encryption and decryption can be done using the same hardware. The results show that with an equivalent security level, SIMON is 86% smaller than AES, 70% smaller than PRESENT (a stan- dardized low-cost AES alternative), and its smallest hardware architec- ture only costs 36 slices (72 LUTs, 30 registers). To our best knowledge, this work sets the new area records as we propose the hardware archi- tecture of the smallest block cipher ever published on FPGAs at 128-bit level of security. Therefore, SIMON is a strong alternative to AES for low-cost FPGA based applications.1 Keywords: Block Ciphers, Light-Weight Cryptography, FPGA Imple- mentation, SIMON. 1 Introduction To implement security in embedded systems, we rely heavily on block ciphers and utilize them in security protocols [5] to store critical information [7], to authenticate identities [4], even to generate pseudo-random numbers [11]. The most popular block cipher is Rijndael which serves as the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES). -

The Conservation Status of Pelagic Sharks and Rays

The Conservation Status of The Conservation Status of Pelagic Sharks and Rays The Conservation Status of Pelagic Sharks and Rays Pelagic Sharks and Rays Report of the IUCN Shark Specialist Group Pelagic Shark Red List Workshop Report of the IUCN Shark Specialist Group Tubney House, University of Oxford, UK, 19–23 February 2007 Pelagic Shark Red List Workshop Compiled and edited by Tubney House, University of Oxford, UK, 19–23 February 2007 Merry D. Camhi, Sarah V. Valenti, Sonja V. Fordham, Sarah L. Fowler and Claudine Gibson Executive Summary This report describes the results of a thematic Red List Workshop held at the University of Oxford’s Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, UK, in 2007, and incorporates seven years (2000–2007) of effort by a large group of Shark Specialist Group members and other experts to evaluate the conservation status of the world’s pelagic sharks and rays. It is a contribution towards the IUCN Species Survival Commission’s Shark Specialist Group’s “Global Shark Red List Assessment.” The Red List assessments of 64 pelagic elasmobranch species are presented, along with an overview of the fisheries, use, trade, and management affecting their conservation. Pelagic sharks and rays are a relatively small group, representing only about 6% (64 species) of the world’s total chondrichthyan fish species. These include both oceanic and semipelagic species of sharks and rays in all major and Claudine Gibson L. Fowler Sarah Fordham, Sonja V. Valenti, V. Camhi, Sarah Merry D. Compiled and edited by oceans of the world. No chimaeras are known to be pelagic. Experts at the workshop used established criteria and all available information to update and complete global and regional species-specific Red List assessments following IUCN protocols. -

Simon and Speck: Block Ciphers for Internet of Things

Simon and Speck: Block Ciphers for the Internet of Things∗ Ray Beaulieu Douglas Shors Jason Smith Stefan Treatman-Clark Bryan Weeks Louis Wingers National Security Agency 9800 Savage Road, Fort Meade, MD, 20755, USA [email protected], {djshors, jksmit3, sgtreat, beweeks, lrwinge}@tycho.ncsc.mil 9 July 2015 Abstract application (e.g., with hard-wired key or for IC print ing), or designing specifically for low-latency appli The U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) developed the Simon and Speck families of cations, and so on. lightweight block ciphers as an aid for securing We would argue that what’s needed in the Internet applications in very constrained environments of Things (IoT) era is not more Kirtland’s warblers where AES may not be suitable. This paper sum and koalas, as wonderful as such animals may be, marizes the algorithms, their design rationale, but crows and coyotes. An animal that eats only eu along with current cryptanalysis and implemen calyptus leaves, even if it outcompetes the koala, will tation results. never become widely distributed. Similarly, a block cipher highly optimized for performance on a partic 1 Introduction ular microcontroller will likely be outcompeted on other platforms, and could be of very limited utility Biologists make a distinction between specialist in 15 years when its target platform is obsolete. species, which occupy narrow ecological niches, and generalists, which can survive in a broader variety of Of course it’s hard to get a handle on block cipher environmental conditions. Specialists include Kirt performance on devices that don’t yet exist. But what land’s warbler, a bird that only nests in 5–20 year-old we can do is strive for simplicity, by designing algo jack pine forests, and the koala, which feeds (almost) rithms around very basic operations that are certain exclusively on eucalyptus leaves. -

Lightweight Block Cipher Circuits for Automotive and Iot Sensor Devices

Lightweight Block Cipher Circuits for Automotive and IoT Sensor Devices Santosh Ghosh, Rafael Misoczki, Li Zhao and Manoj R Sastry SPR/Intel Labs, Intel Corporation Hillsboro, OR, 97124 USA {firstname.middlename.lastname}[at]intel.com HASP 2017 : Hardware and Architectural Support for Security and Privacy 2017 Toronto, Canada June 25, 2017 Security in Automotive and IoT Sensor Devices . IoT devices such as sensors typically have die area and power constraints • Attack against integrity, authentication and confidentiality are the major concerns [3] • This talk focuses on Automotive Security vertical . Electronic Control Units (ECUs) control critical functionality in a car such as braking, acceleration etc • Connected to Controller Area Network (CAN) [1] in a car . Lack of security in CAN has been exploited by hackers [2] • Security (authenticity of the sender, integrity of the messages and replay protections) is challenging because of very restrictive CAN packet format and safety critical applications such as braking and acceleration have a low latency requirement • Question: Whether cryptographic security is feasible? Which crypto algorithm would be best suited? [1] BOSCH, 1991. CAN Specification Version 2.0 [2] Miller, C. and Valasek, C. 2016. Advanced CAN injection techniques for vehicle networks [3] Dhanjani, N. 2013. Hacking lightbulbs: Security evaluation of the Philips hue personal wireless lighting system HASP 2017, Toronto, Canada, June 25, 2017 2 Agenda • Standard cipher algorithm and overhead • New lightweight block ciphers and -

Algebraic Analysis of the Simon Block Cipher Family

Algebraic Analysis of the Simon Block Cipher Family Håvard Raddum Simula Research Laboratory, Norway Abstract. This paper focuses on algebraic attacks on the Simon family of block ciphers. We construct equation systems using multiple plaintext/ciphertext pairs, and show that many vari- ables in the cipher states coming from different plaintexts are linearly related. A simple solving algorithm exploiting these relations is developed and extensively tested on the different Simon variants, giving efficient algebraic attacks on up to 16 rounds of the largest Simon variants. Key words: block cipher, algebraic attack, equation system, Simon 1 Introduction The Simon and Speck families of block cipher were published by the National Security Agency in June 2013 [1]. Both families consist of lightweight block ciphers, where the Simon ciphers are optimized for hardware and the Speck ciphers are optimized for software. The ciphers use very little area and have high throughput. In the publication from the NSA all ciphers were specified, but there was no security analysis. In the relatively short time since the Simon and Speck ciphers became known the cryptographic community has spent a lot of effort cryptanalyzing them. Some work focused on differential cryptanalysis has been published [2,3], as well as a paper on linear cryptanalysis of Simon [4]. Several other papers on cryptanalysis of Simon have also been posted to the IACR eprint archive [5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. The work in [10] is focused on cube attacks, but other than that we have not seen any pub- lished work on Simon’s resistance to algebraic attacks.