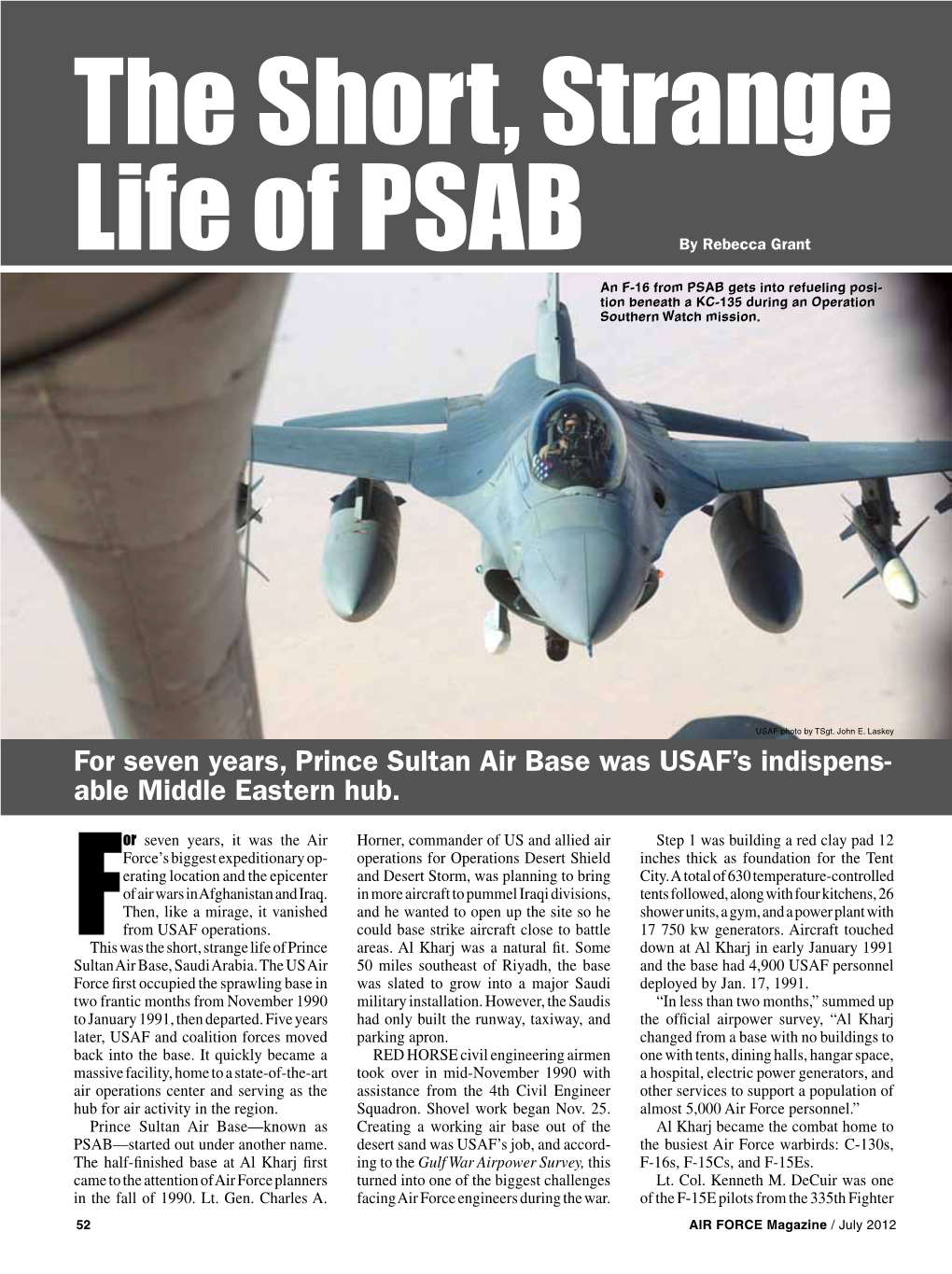

The Short, Strange Life of PSAB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jeannie Leavitt, MWAOHI Interview Transcript

MILITARY WOMEN AVIATORS ORAL HISTORY INITIATIVE Interview No. 14 Transcript Interviewee: Major General Jeannie Leavitt, United States Air Force Date: September 19, 2019 By: Lieutenant Colonel Monica Smith, USAF, Retired Place: National Air and Space Museum South Conference Room 901 D Street SW, Suite 700 Washington, D.C. 20024 SMITH: I’m Monica Smith at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. Today is September 19, 2019, and I have the pleasure of speaking with Major General Jeannie Leavitt, United States Air Force. This interview is being taped as part of the Military Women Aviators Oral History Initiative. It will be archived at the Smithsonian Institution. Welcome, General Leavitt. LEAVITT: Thank you. SMITH: So let’s start by me congratulating you on your recent second star. LEAVITT: Thank you very much. SMITH: You’re welcome. You’re welcome. So you just pinned that [star] on this month. Is that right? LEAVITT: That’s correct, effective 2 September. SMITH: Great. Great. So that’s fantastic, and we’ll get to your promotions and your career later. I just have some boilerplate questions. First, let’s just start with your full name and your occupation. LEAVITT: Okay. Jeannie Marie Leavitt, and I am the Commander of Air Force Recruiting Service. SMITH: Fantastic. So when did you first enter the Air Force? LEAVITT: I was commissioned December 1990, and came on active duty January 1992. SMITH: Okay. And approximately how many total flight hours do you have? LEAVITT: Counting trainers, a little over 3,000. SMITH: And let’s list, for the record, all of the aircraft that you have piloted. -

US Military Policy in the Middle East an Appraisal US Military Policy in the Middle East: an Appraisal

Research Paper Micah Zenko US and Americas Programme | October 2018 US Military Policy in the Middle East An Appraisal US Military Policy in the Middle East: An Appraisal Contents Summary 2 1 Introduction 3 2 Domestic Academic and Political Debates 7 3 Enduring and Current Presence 11 4 Security Cooperation: Training, Advice and Weapons Sales 21 5 Military Policy Objectives in the Middle East 27 Conclusion 31 About the Author 33 Acknowledgments 34 1 | Chatham House US Military Policy in the Middle East: An Appraisal Summary • Despite significant financial expenditure and thousands of lives lost, the American military presence in the Middle East retains bipartisan US support and incurs remarkably little oversight or public debate. Key US activities in the region consist of weapons sales to allied governments, military-to-military training programmes, counterterrorism operations and long-term troop deployments. • The US military presence in the Middle East is the culmination of a common bargain with Middle Eastern governments: security cooperation and military assistance in exchange for US access to military bases in the region. As a result, the US has substantial influence in the Middle East and can project military power quickly. However, working with partners whose interests sometimes conflict with one another has occasionally harmed long-term US objectives. • Since 1980, when President Carter remarked that outside intervention in the interests of the US in the Middle East would be ‘repelled by any means necessary’, the US has maintained a permanent and significant military presence in the region. • Two main schools of thought – ‘offshore balancing’ and ‘forward engagement’ – characterize the debate over the US presence in the Middle East. -

Desert Chill

The US–Saudi marriage of convenience probably won’t end in divorce, but there is plenty of tension in the house. Desert Chill By Peter Grier AST August, Prince Bandar bin be held at all underscores the ten- Sultan—fighter pilot, Johns sions that have arisen lately in one of Hopkins University gradu- the most important of America’s for- Late, and longtime Saudi en- eign relationships. The aggravating voy in Washington—paid a personal factors range from the personal— call on George W. Bush at the Presi- disputes over international child cus- dent’s Crawford, Tex., ranch. The tody—to the global—how to live with American leader escorted Bandar and Israel and what to do about Iraq’s his wife around the 1,600-acre spread. Saddam Hussein. Later, Bush hosted the couple and Bush Administration officials, for six of their eight children at a lunch- their part, have been frustrated at time barbecue. what they view as a reluctance by It was a gesture of friendship of- Saudi Arabia’s aging leadership to fered to few heads of state, let alone recognize the degree to which its diplomats. And it had a purpose. The kingdom has become a breeding President’s hospitality was meant to ground for terrorism and intoler- signal his desire to remain on good ance. Fifteen of the 19 hijackers of terms with the Kingdom of Saudi Sept. 11 were Saudi citizens. Saudi Arabia, a key supplier of the West’s clerics remain the source of some of crude oil and a highly influential the most virulent anti–Semitic and player in Gulf and Arab politics. -

US Policy Priorities in the Gulf: Challenges and Choices Martin Indyk

4 US Policy Priorities in the Gulf: Challenges and Choices Martin Indyk nited States (US) security strategy in the Arabian Gulf has U been dictated by its vital interest in ensuring the free flow of oil at reasonable prices from the oil fields of that region.1 With the elimination of the Iraqi army and its replacement with American forces, the United States is now the dominant power in the Gulf. With bases and access rights in Iraq and most of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states (with the notable exception of Saudi Arabia), the United States is capable of maintaining this dominance for the foreseeable future, even if its efforts to stabilize the situation in Iraq prove hapless. Its greatest challenges are likely to stem from two sources: first, a potential failure to prevent Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons, which could in turn trigger an Israeli preemptive strike and a destabilizing arms race in the region; and second, a ripple effect from instability in Iraq that could impact on the stability of its - 1 - INTERNATIONAL INTERESTS IN THE GULF REGION smaller Arab neighbors, which could in turn undermine the foundations on which America’s security policy is based. To deal with these potential challenges, the United States needs to develop a security architecture for the Gulf that will take into account the legitimate security concerns of all the states in the Gulf, including Iran, and thereby defuse the potential for nuclear proliferation in this volatile region. At the same time, it will need to stabilize the situation in Iraq in ways that ensure its ability to maintain a security presence in the region for the foreseeable future. -

OVERSEAS CONTINGENCY OPERATIONS TRANSFER FUND FY 2001 President’S Budget Submission

OVERSEAS CONTINGENCY OPERATIONS TRANSFER FUND FY 2001 President’s Budget Submission Table of Contents Page No. DoD Total Description of Operations Financed...................................................................................................................... 1 Financial Summary............................................................................................................................................... 5 Summary of Increases/Decreases.......................................................................................................................... 6 Summary by Service and Operation...................................................................................................................... 10 Army Requirements Bosnia.................................................................................................................................................................. 15 Kosovo................................................................................................................................................................ 20 Southwest Asia .................................................................................................................................................... 25 East Timor ........................................................................................................................................................... 30 Navy Requirements Bosnia................................................................................................................................................................. -

Up from Kitty Hawk Chronology

airforcemag.com Up From Kitty Hawk Chronology AIR FORCE Magazine's Aerospace Chronology Up From Kitty Hawk PART ONE PART TWO 1903-1979 1980-present 1 airforcemag.com Up From Kitty Hawk Chronology Up From Kitty Hawk 1980-1989 F-117 Nighthawk stealth fighters, first flight June 1981. Articles noted throughout the chronology are hyperlinked to the online archive for Air Force Magazine and the Daily Report. 1980 March 12-14, 1980. Two B-52 crews fly nonstop around the world in 43.5 hours, covering 21,256 statute miles, averaging 488 mph, and carrying out sea surveillance/reconnaissance missions. April 24, 1980. In the middle of an attempt to rescue US citizens held hostage in Iran, mechanical difficulties force several Navy RH-53 helicopter crews to turn back. Later, one of the RH-53s collides with an Air Force HC-130 in a sandstorm at the Desert One refueling site. Eight US servicemen are killed. Desert One May 18-June 5, 1980. Following the eruption of Mount Saint Helens in northwest Washington State, the Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Service, Military Airlift Command, and the 9th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing conduct humanitarian-relief efforts: Helicopter crews lift 61 people to safety, while SR–71 airplanes conduct aerial photographic reconnaissance. May 28, 1980. The Air Force Academy graduates its first female cadets. Ninety-seven women are commissioned as second lieutenants. Lt. Kathleen Conly graduates eighth in her class. Aug. 22, 1980. The Department of Defense reveals existence of stealth technology that “enables the United States to build manned and unmanned aircraft that cannot be successfully intercepted with existing air defense systems.” Sept. -

Capt Patrick C

LtCol Jeremy W. Beaven, USMC Lieutenant Colonel Beaven graduated from York College of Pennsylvania in May 1997. He completed Officer Candidate School via the Platoon Leaders Course and was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in April 1998. After completion of The Basic School, Second Lieutenant Beaven reported to the Navy and Marine Corps Intelligence Training Center, Dam Neck, VA and was designated as an Air Intelligence Officer in June 1999. Upon graduation, Second Lieutenant Beaven was selected as the RADM Donald M. Showers award recipient for superior achievement. Second Lieutenant Beaven then reported for duty with Marine Aircraft Group 14 (MAG-14) aboard MCAS Cherry Point, NC and was assigned to Marine Tactical Electronic Warfare Squadron Three (VMAQ-3). During his three-year tour as an Intelligence Officer with VMAQ-3, he completed the Basic Airborne Course at the U.S. Army Infantry School, Ft Benning, GA and deployed to Prince Sultan Air Base, Saudi Arabia in support of Operation SOUTHERN WATCH, and Incirlik Air Base, Turkey in support of Operation NORTHERN WATCH. While deployed, First Lieutenant Beaven was selected for transition to the Naval Flight Officer program. In May 2002, Captain Beaven reported to Marine Aviation Training Support Group Twenty One aboard NAS Pensacola, FL for Aviation Preflight Indoctrination. He conducted basic and intermediate flight training at Training Squadron 4, with advanced training at Training Squadron 86. Captain Beaven was placed on the Commodore’s List with Distinction for all phases of flight training. He was designated a Naval Flight Officer in September 2003 and was subsequently selected as the 2003 RADM Thurston H. -

U.S. Security Architecture in the Gulf: Elements and Challenges by James Russell and Iliana Bravo

Strategic Insight U.S. Security Architecture in the Gulf: Elements and Challenges by James Russell and Iliana Bravo Strategic Insights are authored monthly by analysts with the Center for Contemporary Conflict (CCC). The CCC is the research arm of the National Security Affairs Department at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Naval Postgraduate School, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. February/March 2002 Introduction The United States has vital national interests throughout the Middle East and Persian Gulf, including the free flow of oil from the Persian Gulf to the international economy, the security of Israel and other key regional partners, a durable Arab-Israeli peace, and the availability of the major air and sea lanes connecting Europe and the Mediterranean with Asia, Africa, and the Indian Ocean. In support of these interests, U.S. military forces are actively engaged in the containment of Iraq and in working to construct a more stable international environment in the region. The United States maintains active and robust security relationships with all the countries in the Gulf. Since the end of the Gulf War, the United States, together with its regional partners, has constructed a regional security architecture composed of the following main elements: forward U.S. military presence; prepositioned military equipment and access to host nation facilities; working with regional partners to boost host nation defense capabilities and U.S.- coalition interoperability through foreign military sales and training; and regional engagement through joint military exercises. -

Experience from Prince Sultan Air Base and Eskan Village in Saudi Arabia

CHILD POLICY This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CIVIL JUSTICE service of the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE 6 INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS NATIONAL SECURITY The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY organization providing objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SUBSTANCE ABUSE and private sectors around the world. TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Project AIR FORCE View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. This product is part of the RAND Corporation documented briefing series. RAND documented briefings are based on research briefed to a client, sponsor, or targeted au- dience and provide additional information on a specific topic. Although documented briefings have been peer reviewed, they are not expected to be comprehensive and may present preliminary findings. The Role of Deployments in Competency Development Experience from Prince Sultan Air Base and Eskan Village in Saudi Arabia LAURA WERBER CASTANEDA, LAWRENCE M. HANSER, CONSTANCE H. DAVIS DB-435-AF April 2004 Prepared for the United States Air Force Approved for public release; distribution unlimited The research reported here was sponsored by the United States Air Force under Contract F49642-01-C-0003. -

Applying Lean to the AC-130 Maintenance Process for the Royal Saudi Air Force Fisal A

Air Force Institute of Technology AFIT Scholar Theses and Dissertations Student Graduate Works 9-15-2016 Applying Lean to the AC-130 Maintenance Process for the Royal Saudi Air Force Fisal A. Alzahrani Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.afit.edu/etd Part of the Management and Operations Commons, and the Operations and Supply Chain Management Commons Recommended Citation Alzahrani, Fisal A., "Applying Lean to the AC-130 Maintenance Process for the Royal Saudi Air Force" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 262. https://scholar.afit.edu/etd/262 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Graduate Works at AFIT Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AFIT Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. APPLYING LEAN TO THE AC-130 MAINTENANCE PROCESS FOR THE ROYAL SAUDI AIR FORCE THESIS SEPTEMPER 2016 Alzahrani Fisal Ali, Captain, Royal Saudi Air Force AFIT-ENS-MS-16-S-024 DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE AIR UNIVERSITY AIR FORCE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A. APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE; DISTRIBUTION UNLIMITED. The views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the United States Air Force, Department of Defense, or the United States Government, the corresponding agencies of any other government, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization or any other defense organization. AFIT-ENS-MS-16-S-024 APPLYING LEAN TO THE AC-130 MAINTENANCE PROCESS FOR THE ROYAL SAUDI AIR FORCE THESIS Presented to the Faculty Department of Operational Sciences Graduate School of Engineering and Management Air Force Institute of Technology Air University Air Education and Training Command In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Logistics and Supply Chain Management Alzahrani Fisal Ali, BS Captain, Royal Saudi Air Force September 2016 DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A. -

Missile Testing and US Middle East Policy

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 631 Missing a Target: Missile Testing and U.S. Middle East Policy by Simon Henderson Jun 28, 2002 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Simon Henderson Simon Henderson is the Baker fellow and director of the Bernstein Program on Gulf and Energy Policy at The Washington Institute, specializing in energy matters and the conservative Arab states of the Persian Gulf. Brief Analysis ver the course of a few days at the end of May, Iran conducted a missile test; Pakistan conducted three such O tests; and Israel launched a reconnaissance satellite. Each of these instances serve as proof, if any were needed, that missiles are becoming an important part of the military scene in the Middle East and Southwest Asia. The question for Washington is how the growing sophistication of Middle East/Southwest Asian missiles will affect the stability of this volatile region. The Missile Tests Iran. Iran's missile test in May involved a variant of the North Korean Nodong, which the Iranians call the Shahab-3. Along with Iraq, Iran made extensive use of less advanced Scud-type missiles in the 1980-1988 war, when both sides targeted the other's capitals and major cities. Although only high-explosive warheads were used, the damage was extensive and the impact on public morale was even greater. The Shahab's reported 800-mile range makes targets in Israel accessible as well as air bases used by the United States in Saudi Arabia -- where the Combined Air Operations Center at the Prince Sultan Air Base would be vulnerable -- and Turkey. -

Iraq and the Gulf States

UNITED STATES InsTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT I R AQ AND I T S N EIGHBO rs Iraq’s neighbors are playing a major role—both positive and negative—in the country’s worsening crisis. As part of the Institute’s Iraq and Its Neighbors project, a group of leading Jon B. Alterman specialists on the geopolitics of the region is assessing the interests and influence of the countries surrounding Iraq and the impact on U.S. bilateral relations. The Institute is also sponsoring high-level, nonofficial dialogue between Iraqi national security and foreign policy officials and their Iraq and counterparts from the neighboring countries. The Marmara Declaration, released after the Institute’s most recent dialogue in Istanbul, sets forth a framework for a regional peace process. Jon Alterman’s report on the Gulf States is the fifth in a series the Gulf of special reports sponsored by the Iraq and Its Neighbors project; Steve Simon’s study on Syria will be published in the coming months. Scott Lasensky, senior research associate at States the Institute’s Center for Conflict Analysis and Prevention and adjunct professor of government at Georgetown University, directs the Iraq and Its Neighbors project and authored the The Balance of Fear report on Jordan. Peter Pavilionis is the series editor. For more information about the Iraq and Its Neighbors project, go to www.usip.org/iraq/neighbors/index.html. Summary Jon B. Alterman is a senior fellow and director of the Middle East Program at the Center for Strategic and International • Iraq’s Persian Gulf neighbors supported the U.S.