Rat and Lagomorph Eradication on Two Large Islands of Central Mediterranean: Diff Erences in Island Morphology and Consequences on Methods, Problems and Targets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Active Foodies in Elba Island Hike and Cook with Locals in a Tuscan Island

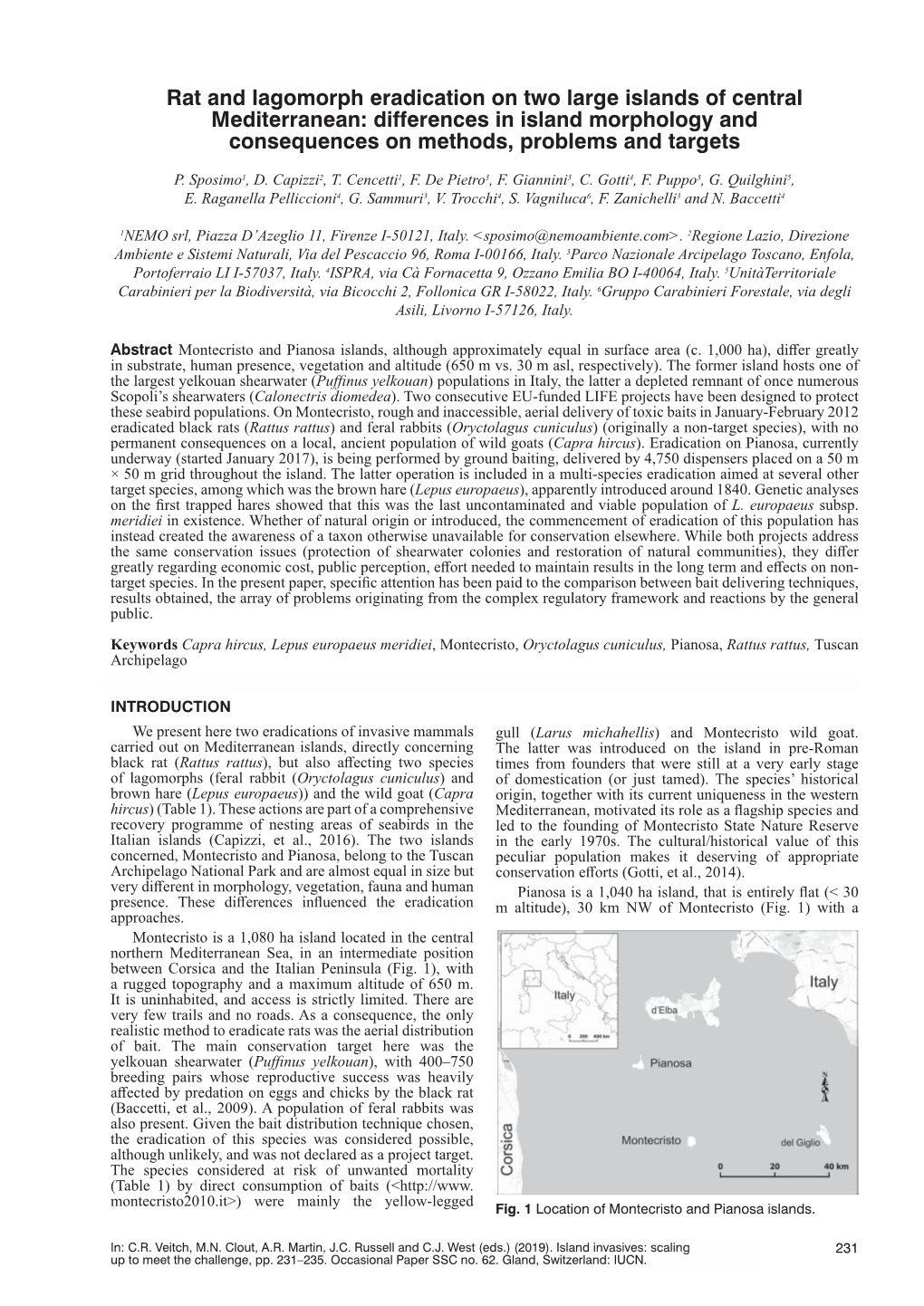

ACTIVE FOODIES IN ELBA ISLAND HIKE AND COOK WITH LOCALS IN A TUSCAN ISLAND DESTINATION ELBA ISLAND, TUSCANY, ITALY DURATION 3 DAYS / 2 NIGHTS ACCOMMODATIONS HOTEL 3* FOCUS HIKING, FOOD AND WINE, COOKING CLASS ACTIVITY LEVEL MODERATE HOSTED IN ENGLISH LEAD TRIP LEADER DESTINATION The Tuscan Archipelago National Park is the largest marine park in Europe and it includes the seven main islands off the coast of Tuscany: Elba, Capraia, Gorgona, Pianosa, Montecristo, Giglio and Giannutri. The geological formation of each islands is very different hinting at its diversity. Elba Island is an ideal destination for outdoor activity lovers and for those who want to enjoy a holiday that combines nature, crystal-clear sea, and physical activity. Thanks to the mild climate of the island, all types of outdoor activities continue throughout the spring and autumn from easy beach strolls, to trail hikes and extreme sports in the water or on the cliff faces. Too big to be small and too small to be big, Elba is the third largest island in Italy: 224 sq Km, 7 municipalities, 32000 inhabitants, over 100 beaches, and a mountain over 1000 m of height. It boasts chestnut woods, lush oak woods, scented Mediterranean vegetation, iron mines, Roman churches, medieval villages, Renaissance fortresses, imperial residences. Elba is not an isolated island in the blue of the Tyrrhenian Sea, but the beating heart of the Tuscan Archipelago. ACTIVE TRAVEL TUSCANY is a brand of VIAGGI DEL GENIO T.O. di Turismo Sostenibile Srl - Piazza Virgilio, 34 - Portoferraio - Isola d'Elba - Italy - VAT. 01708200496 - Phone (0039) 0565 944374 Fax (0039) 0565 919809 - [email protected] www.activetraveltuscany.com TRIP SUMMARY FOR GUESTS Get off the beaten path of the typical Tuscany tours and enjoy 3 exciting active days on the magical paradise island of Elba. -

Get App Archaeological Itineraries In

TUSCANY ARCHAEOLOGICAL ITINERARIES A Journey from Prehistory to the Roman Age ONCE UPON A TIME... That’s how fables start, once upon a time there was – what? A region bathed by the sea, with long beaches the colour of gold, rocky cliffs plunging into crystalline waters and many islands dotting the horizon. There was once a region cov- ered by rolling hills, where the sun lavished all the colours of the earth, where olive trees and grapevines still grow, ancient as the history of man, and where fortified towns and cities seem open-air museums. There was once a region with ver- dant plains watered by rivers and streams, surrounded by high mountains, monasteries, and forests stretching as far as the eye could see. There was, in a word, Tuscany, a region that has always been synonymous with beauty and nature, art and history, especially Medieval and Renaissance history, a land whose fame has spread the world over. And yet, if we stop to look closely, this region offers us many more treasures and new histories, the emotion aroused only by beauty. Because along with the most famous places, monuments and museums, we can glimpse a Tuscany that is even more ancient and just as wonderful, bear- ing witness not only to Roman and Etruscan times but even to prehistoric ages. Although this evidence is not as well known as the treasures that has always been famous, it is just as exciting to discover. This travel diary, ad- dressed to all lovers of Tuscany eager to explore its more hidden aspects, aims to bring us back in time to discover these jewels. -

Montecristo 2010 Project Eradication of Invasive Plant and Animal Aliens and Conservation of Species/Habitats in the Tuscan Archipelago, Italy

Montecristo 2010 Project eradication of invasive plant and animal aliens and conservation of species/habitats in the Tuscan Archipelago, Italy Montecristo 2010 Project eradication of invasive plant and animal aliens and conservation of species/habitats in the Tuscan Archipelago, Italy eradication of invasive management tools preservation alien species techniques PROJECT DESCRIPTION The ecosystems of the islands of Montecristo and Pianosa, protected natural sanctuaries located in the Tuscan Archipelago National Park, have been deeply modified by the presence of some invasive alien species introduced, voluntarily or accidentally, over the centuries by inhabitants and visitors. The MONTECRISTO project aimed to eradicate the black rat and ailanthus from the island, two of the three invasive alien species that threatened the area's biodiversity. For the third alien species, a strain very close to the wild goat, the project did not foresee eradication, but its containment. This because of the historical and cultural value of this ancient animal population whose conservation constitutes one of the requirements for the award of the "European Diploma for protected areas" attributed to the Montecristo reserve in 1988. The wild goat, introduced in ancient times, is crucial for the renewal of any plant species that enters its diet. On the island of Pianosa, however, the project envisaged the eradication of 4 invasive plant species spread on the island, the Hottentot-fig (Carpobrotus edulis), the Acacias, the Senecio and the Ailanthus (Ailanthus altissima), and the protection of the precious coastal junipers, invaded by the spreading of Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis) a forest species introduced intentionally because its capacity of producing stable and resistant formations. -

Nature Notebooks of the Tuscan Archipelago

n2000 communication award Best COMMUNICATION CASE STUDIES, 2015 Nature notebooks of the Tuscan Archipelago The Park has commissioned artists to the realization of naturalistic LOCATION Notebooks illustrating so painterly landscapes and biodiversity of Nat- TUSCAN ARCHIPELAGO, ura 2000 sites of the seven protected islands of the Tuscan ITALY Archipelago. Natura 2000 sites islands An original editorial product that promotes the use related to the Capraia and Pianosa Giglio, Tuscan National Park discovery of nature. In 2015 they were made the first three volumes relating to Capraia, Pianosa and Giglio that are now being presented to the public through the suggestion of the visit live on the islands painted. In 2016 the series will be completed with Gorgona, Montecristo, Giannutri and Elba course that is the most challenging, because of its large size and variability. The promotion of the collection of the emotional guidebooks was A series of notebooks launched with the radio frequencies of the Moratorium National Radio nature made “real” and Capital, which organizes the program directly “on the field”, interviewing dedicated to the the residents of the area and telling the values of nature and culture of our 7 islands of the Tuscan islands. Presentation at book fairs and in the municipalities of the islands Archipelago concerned. Show Forte English in Portoferraio with music Conferences debates and tastings. (Capraia, Elba, Giannutri, Gi- glio, Gorgona, Montecristo The project was funded by the National Park. and Pianosa), developed by EDT -

A Shallow Mud Volcano in the Sedimentary Basin Off the Island of Elba

A shallow mud volcano in the sedimentary basin off the Island of Elba Alessandra Sciarra1,2, Anna Saroni2, Fausto Grassa3, Roberta Ivaldi4, Maurizio Demarte4, Christian Lott5, Miriam Weber5, Andreas Eich5, Ettore Cimenti4, Francesco Mazzarini6 and Massimo Coltorti2,3 •1Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, Roma 1, Italy ([email protected]) •2Department of Physics and Earth Sciences, University of Ferrara, Italy. •3Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, Palermo, Italy •4Istituto Idrografico della Marina, Italy •5HYDRA Marine Sciences GmbH, Burgweg 4, 76547, Sinzheim, Germany •6Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, Pisa, Italy Elba Island The Island of Elba, located in the westernmost portion of the northern Cenozoic Apennine belt, is formed by metamorphic and non-metamorphic units derived from oceanic (i.e. Ligurian Domain) and continental (i.e. the Tuscan Domain) domains stacked toward NE during the Miocene (Massa et al., 2017). Offshore, west of the Island of Elba, magnetic and gravimetric data suggest the occurrence of N-S trending ridges that, for the very high magnetic susceptibility, have been interpreted as serpentinites, associated with other ophiolitic rocks (Eriksson and Savelli, 1989; Cassano et al., 2001; Caratori Tontini et al., 2004). Moving towards south in Tuscan domain, along N-S fault, there is clear evidence of off- shore gas seepage (mainly CH4), which can be related to recent extensional activity. Scoglio d’Affrica site Bathymetric map of the area between the island of Elba and Montecristo showing the location of Scoglio d’Affrica emission site, Pomonte seeps and Pianosa emission site. In the inset locations of the Scoglio d’Affrica emission activities detected in 2011 (HYDRA Institute, 2011; Meister et al. -

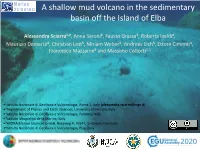

Corsica Isola Di Capraia Isola Di Pianosa

ISOLA DI PIANOSA CORSICA ISOLA DI CAPRAIA Tutti i giorni / All week days Domenica / Sunday Venerdì / Friday partenza da: partenza da: partenza da: departure from: MARINA DI CAMPO 10,00 departure from: PORTOFERRAIO 9,15 departure from: PORTOFERRAIO 9,30 arrivo a: ISOLA DI PIANOSA arrivo a: partenza da: arrival at: ISOLA DI PIANOSA 10,30 arrival at: BASTIA (FRANCIA) 11,30 departure from: MARCIANA MARINA 10,00 LE PROPOSTE DEL PARCO NAZIONALE sosta di 6 ore e 30 minuti all’Isola di Pianosa sosta di 5 ore a Bastia arrivo a: Visita del paese arrival at: ISOLA DI CAPRAIA 11,30 6 hours and 30 minutes stop at Pianosa Island Una passeggiata tra le suggestive strutture del borgo di Pianosa per conoscere la storia 5 hours stop at Bastia e le abitudini delle comunità che qui hanno vissuto, in un percorso storico che va dall’età sosta di 5 ore all’Isola di Capraia partenza da: della pietra agli insediamenti ottocenteschi. Il martedì il servizio è destinato ai passeggeri del partenza da: departure from: ISOLA DI PIANOSA 17,00 traghetto Toremar e si conclude con la visita del complesso archeologico Bagni di Agrippa. departure from: BASTIA 16,30 5 hours stop at Capraia Island Durata: 1h.30’. ? 5,00, esenti bambini (0-4 anni). arrivo a: arrivo a: partenza da: arrival at: MARINA DI CAMPO 17,40 Trekking archeologico arrival at: PORTOFERRAIO 18,45 departure from: ISOLA DI CAPRAIA 16,30 Si raggiungono aree di recente scavo che hanno messo in luce importanti testimonianze arrivo a: archeologiche. Si arriva al Belvedere, il punto più alto dell’isola, dal quale si può ammirare il arrival at: MARCIANA MARINA 18,00 TARIFFE escluso ticket* / FARES entrance fee not included* paesaggio circostante. -

SESS 1 160211.Pub

Il Quaternario Congresso AIQUA Italian Journal of Quaternary Sciences Il Quaternario Italiano: conoscenze e prospettive 24, (Abstract AIQUA, Roma 02/2011), 32 - 34 Roma 24 e 25 febbraio 2011 UPPER PLEISTOCENE-HOLOCENE RELATIVE SEA LEVEL CHANGES AT PIANOSA ISLAND (TUSCANY ARCHIPELAGO): GEOLOGICAL, GEOMORPHOLOGICAL AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL MARKERS 1Luca Maria Foresi, 2Fabrizio Antonioli, 3Maurizio D’Orefice, 4Silvia Ducci, 5Marco Firmati, 3Roberto Graciotti, 3Marco Pantaloni, 4Paola Perazzi & 6Claudia Principe 1Dipartimento di Scienze dellaTerra, Università di Siena, Siena 2Enea, Casaccia, Roma 3ISPRA – Servizio Geologico d’Italia, Roma 4Soprintendenza per i beni archeologici della Toscana, Firenze 5Museo Archeologico del Distretto Minerario di Rio nell’Elba, Livorno 6Istituto di Geoscienze e Georisorse, Archaeomagnetic Laboratory, Pisa Corresponding author: L. M. Foresi <[email protected]> ABSTRACT: Foresi L.M. et al., Upper Pleistocene-Holocene relative sea level changes at Pianosa Island (Tuscany Archipelago): geological, geomorphological and archaeological markers. (IT ISSN 0394-3356, 2011). Based on geological, geomorphological and archaeological markers, we provides new data and interpretations on the relative sea level change occurred at Pianosa Island (Italy) since the last 125 ka. The MIS 5.5 deposits are characterized by a 2 m thick whitish fossiliferous calcarenite, cropping out at a maximum altitude of 4 m a.s.l. containing Strombus bubonius. Archaeological remains provide evidence of sea level change for the last 8 ka. Particularly useful are some fishtanks and a quarry cut around 2 ka BP (Roman age). RIASSUNTO: Foresi L.M. et al., Variazioni relative del livello del mare nell’Isola di Pianosa (Arcipelago Toscano) nel Pleistocene superiore-Olocene: markers geologici, geomorfologici e archeologici. (IT ISSN 0394-3356, 2011). -

1 Week Elba Island, Capraia & Corse

CRUISE ADVANCED 1.2 SAINT FLORENT (CORSE) 1 WEEK ELBA ISLAND, CAPRAIA & CORSE GOLFO DI VITICCIO • MARCIANA MARINA • CAPRAIA ISLAND • CENTURI SAINT FLORENT • GIRAGLIA • MACINAGGIO • FETOVAIA • MARINA DI CAMPO CRUISE ADVANCED 1 WEEK ELBA ISLAND, CAPRAIA & CORSE CAPRAIA TUSCANY CHART ISLAND PUNTA DELLO ZENOBITO MACINAGGIO CENTURI PIOMBINO PUNTONE DI SCARLINO PALMAIOLA CERBOLI ELBA ISLAND GOLFO PORTOFERRAIO PUNTA ALA MARCIANA DEL VITICCIO MARINA MARINA DI CAMPO GROSSETO FETOVAIA PORTO AZZURRO SAINT FLORENT BASTIA PIANOSA ISLAND FORMICHE DI TALAMONE CORSE GROSSETO Base Departure - Marina di Scarlino PORTO ERCOLE PORTO TYRRHENIAN SANTO STEFANO GIGLIO CAMPESE SEA GIGLIO PORTO “Marina di Scarlino” is located in the Tuscan Maremma, GIGLIO MONTECRISTO ISLAND in an area of pinewoods, wooded hills and olive groves, ISLAND CALA MAESTRA with untouched coastlines, kilometers of natural parks, CALA DELLO SPALMATOIO and a crystalline blue sea. It is the perfect point of de- GIANNUTRI ISLAND parture for brief sailing trips to Elba, Giglio, Argentario, Capraia – and a little further away, Corsica and Sardinia. DISTANCE IN NAUTICAL MILES The services on offer within the Marina will make your stay MARINA DI SCARLINO - GOLFO DI VITICCIO - MARCIANA MARINA 28 truly comfortable. Other than showers and washrooms, MARCIANA MARINA - CAPRAIA ISLAND 22 and free Wi-Fi, there is the shopping arcade close to our of- fice, with numerous shops to satisfy every need, amongst • MARINA DI SCARLINO • GOLFO DI VITICCIO CAPRAIA ISLAND - CENTURI - SAINT FLORENT 54 HARBOURS ANCHORS which a supermarket, a launderette, a ship chandler, cafés, • MARCIANA MARINA • CAPRAIA ISLAND restaurants, as well as the “Marina Club Pool and Lounge”, • CAPRAIA ISLAND • CENTURI SAINT FLORENT - GIRAGLIA - MACINAGGIO 30 with swimming pool, hydro-massage and solarium. -

Evento Pianosa

Scheda tecnica per il 14 maggio – evento Pianosa Per raggiungere l’isola di Pianosa è necessaria la prenotazione con la compagnia di navigazione Aquavision (unica autorizzata al trasporto marittimo sull’isola). NB*: Il Parco Nazionale dell’Arcipelago Toscano consente l’accesso ad un numero limitato di visitatori, è quindi opportuno effettuare la prenotazione prima possibile, mettendo in copia la nostra Sezione [email protected] A Q U A V I S I O N servizi turistici marittimi 0565 976022 & 328 7095470 [email protected] www.aquavision.it Questo l’itinerario di viaggio: partenza da: Marina di Campo 10:15 arrivo a: Isola di Pianosa 11:00 sosta di 6 ore all’Isola di Pianosa partenza da: Isola di Pianosa 17:00 arrivo a: Marina di Campo 17:45 È necessario acquistare il biglietto prenotato presso la biglietteria Aquavision in Piazza dei Marinai d’Italia (a Marina di Campo) non più tardi delle ore 9,30 Adulti ordinari A/R € 23,60 + ticket Parco € 6,00 e bambini 4-12 anni € 11,80 Residenti Arcipelago Toscano A/R € 9,40 e bambini 4-12 anni € 4,70 Programma della giornata: visita guidata del paese; visita agli Orti, inaugurazione della nuova LIMONAIA, pranzo nell’Orto a cura dei Detenuti stessi; visita della Villa Romana di Agrippa. Tempo libero. In questa occasione la Sezione Arcipelago Toscano di Italia Nostra consegnerà al nostro referente per l’isola, Claudio Cuboni, alcune piante di Rosa Rugosa destinate a selezionate aree verdi del piccolo paese. I soci che desiderano partecipare a questa donazione potranno versare € 10,00. -

The Count of Monte Cristo Novel by Dumas Print Cite Share More

The Count of Monte Cristo novel by Dumas Print Cite Share More WRITTEN BY Patricia Bauer See All Contributors Patricia Bauer is an Assistant Editor at Encyclopaedia Britannica. She has a B.A. with a double major in Spanish and in theatre arts from Ripon College. She previously worked on the Britannica Book of... See Article History Alternative Title: “Le Comte de Monte-Cristo” The Count of Monte Cristo, French Le Comte de Monte- Cristo, Romantic novel by French author Alexandre Dumas père (possibly in collaboration with Auguste Maquet), published serially in 1844–46 and in book form in 1844–45. The work, which is set during the time of the Bourbon Restoration in France, tells the story of an unjustly incarcerated man who escapes to find revenge. Count of Monte Cristo, The The count of Monte Cristo, from a 2003 French stamp. © Neftali/Shutterstock.com BRITANNICA QUIZ Name the Novelist Every answer in this quiz is the name of a novelist. How many do you know? Summary The novel opens in 1815 as the Pharaon arrives in Marseille. The ship’s owner, Monsieur Morrel, learns from the young first mate, Edmond Dantès, that the captain died on the journey and that Dantès took over. The ship’s accountant, Danglars, is bothered that the Pharaon stopped at Elba, but Dantès explains that the captain left a package to be delivered to one of Napoleon’s marshals who is in exile with Napoleon on the island. Morrel makes Dantès captain of the ship, to Danglars’s displeasure. On visiting his father, Dantès learns that a neighbour, Gaspard Caderousse, took most of his father’s resources in payment of a debt. -

05 Motteran-Ventura

Atti Soc. tosc. Sci. nat., Mem., Serie A, 110 (2005) pagg. 51-60, figg. 16, tabb. 2 G. MOTTERAN (*), G. VENTURA (*) ASPETTI GEOLOGICI, MORFOLOGICI E AMBIENTALI DELLO SCOGLIO D’AFRICA (ARCIPELAGO TOSCANO): NOTA PRELIMINARE Riassunto - È stato effettuato uno studio sulla geologia e la d’Africa sono piuttosto scarsi. Questo fatto è da impu- geomorfologia della parte emersa dello Scoglio d’Africa. Le tarsi più che ad una mancanza di interesse scientifico, osservazioni effettuate in campagna e quelle derivate dall’a- alle difficoltà di accesso all’isola. Si tratta infatti di una nalisi di sezioni sottili di alcuni campioni di rocce hanno ridottissima superficie di terra affiorante per pochi messo in evidenza, nell’ambito del calcare organogeno affio- metri di altezza sul livello del mare, il cui raggiungi- rante, due diversi ambienti di sedimentazione entrambi rife- ribili al Pleistocene s.l. Le considerazioni di carattere ambien- mento è subordinato alle condizioni meteorologiche e tale relative all’abbondante posidonieto e al Coralligeno pre- all’andamento delle maree. L’isola è infatti frequente- senti nei fondali mettono in evidenza la sua particolare valen- mente battuta dai venti e dalle correnti ed è circondata za ecologica. Del resto la legislazione vigente ribadisce l’e- da scogli subaffioranti che rendono pericoloso l’avvi- levata naturalità di questo biotopo dell’Arcipelago Toscano. cinamento; l’ormeggio è possibile solo con mare cal- mo tramite un piccolissimo molo utilizzato in caso di Parole chiave - Scoglio d’Africa, Arcipelago Toscano, necessità di manutenzione del faro, unica costruzione Geologia, Geomorfologia, Ecologia. presente (Fig. 1). Abstract - Geological, Geomorphological and Enviromental features of the Scoglio d’Africa (Tuscan islands): prelimi- nary results. -

L'arcipelago Toscano

TOUR TANTE ESCURSIONI IN UN SOGGIORNO MARE L’ARCIPELAGO TOSCANO Dall’Elba al Giglio e Pianosa. Vita di mare e voglia di conoscere Dal 20 al 27 giugno 2021 (8 gg / 7 notti) Una settimana in Villaggio al UAPPALA HOTEL di Lacona sulla più grande e bella spiaggia dell’isola d’Elba. Escursioni in bus privato alla scoperta dell’isola e due giornate dedicate alle belle isole del Giglio e di Pianosa. Perle nell’arcipelago toscano. QUOTA INDIVIDUALE DI PARTECIPAZIONE 20 - 27 giugno € 1.000 Suppl. Singola € 290 Quota iscrizione € 35 LA QUOTA COMPRENDE: Viaggio in pullman GT - Passaggio marittimo (traghetto bus e passeggeri) - Sistemazione in villaggio 4 stelle sul mare con animazione – Servizio spiaggia - Trattamento di pensione completa - Bevande ai pasti - Visite guidate come da programma - Ingressi: Villa Romana, Miniera di Rio Marina con Trenino, Acqua dell’Elba, Villa dei Mulini - Escursione all’isola del Giglio e a Pianosa - Assicurazione medico/bagaglio con copertura Cover Stay – Auricolari individuali - Accompagnatore LeMarmotte. LA QUOTA NON COMPRENDE: Tassa di soggiorno – Mance - Ingressi e visite non indicate - Polizza annullamento facoltativa € 40 da richiedere all’atto della prenotazione - Extra di carattere personale e tutto quanto non indicato ne “la quota comprende”. NOTE: La tutela dei clienti è la nostra priorità. Pertanto i programmi saranno effettuati rispettando le normative distanziamento in essere al momento dell’effettuazione del viaggio. Eventuali variazioni di programma e/o di quote dovute al loro rispetto, verranno prontamente comunicate a ciascun iscritto. In caso di disposizioni governative che vietassero lo svolgimento dei viaggi gli importi versati saranno restituiti ai clienti senza l’emissione di voucher.