Dirigo Flyer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

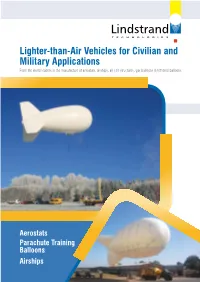

Lighter-Than-Air Vehicles for Civilian and Military Applications

Lighter-than-Air Vehicles for Civilian and Military Applications From the world leaders in the manufacture of aerostats, airships, air cell structures, gas balloons & tethered balloons Aerostats Parachute Training Balloons Airships Nose Docking and PARACHUTE TRAINING BALLOONS Mooring Mast System The airborne Parachute Training Balloon system (PTB) is used to give preliminary training in static line parachute jumping. For this purpose, an Instructor and a number of trainees are carried to the operational height in a balloon car, the winch is stopped, and when certain conditions are satisfied, the trainees are dispatched and make their parachute descent from the balloon car. GA-22 Airship Fully Autonomous AIRSHIPS An airship or dirigible is a type of aerostat or “lighter-than-air aircraft” that can be steered and propelled through the air using rudders and propellers or other thrust mechanisms. Unlike aerodynamic aircraft such as fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters, which produce lift by moving a wing through the air, aerostatic aircraft, and unlike hot air balloons, stay aloft by filling a large cavity with a AEROSTATS lifting gas. The main types of airship are non rigid (blimps), semi-rigid and rigid. Non rigid Aerostats are a cost effective and efficient way to raise a payload to a required altitude. airships use a pressure level in excess of the surrounding air pressure to retain Also known as a blimp or kite aerostat, aerostats have been in use since the early 19th century their shape during flight. Unlike the rigid design, the non-rigid airship’s gas for a variety of observation purposes. -

Goodyear – Civilian Blimps

Goodyear – civilian blimps Peter Lobner, 24 August 2021 1. Introduction Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company began their involvement with lighter-than-air (LTA) vehicles in 1912, when the company developed a fabric envelope suitable for use in airships and aerostats. The first blimps manufactured by the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company were B-Type blimps ordered by the US Navy in 1917 for convoy escort duty. Goodyear (envelope supplier) and Curtiss Aeroplane (gondola supplier) produced 9 of the 17 B-Type blimps ordered. Goodyear also supplied the envelopes for some of the Navy’s 10 C-Type patrol blimps, which were delivered in 1918, after the end of WW I. Both the B- and C-Type blimps used hydrogen as the lift gas. In 1923, Goodyear teamed with German firm Luftschiffbau Zeppelin and created a new subsidiary, Goodyear Zeppelin Corporation. In June 1925, their Type AD Pilgrim (NC-9A) made its first flight and became Goodyear’s first blimp to use helium lift gas. Pilgrim was certified later in 1925, becoming the first US commercial airship. Goodyear Zeppelin Corporation filed a patent application for a nonrigid airship in September 1929, describing the objectives of their invention as follows: “This invention relates to non-rigid airships, and it has particular relation to the suspension of pilot cars or gondolas from the envelopes of non-rigid airships. The principal object of the invention is to provide a non-rigid airship in which the envelope and the pilot car or engine car are so constructed as to offer the minimum air resistance. Another object of the invention is to provide connections between the envelope and pilot car that are not exposed to the airstream for sustaining the weight of the pilot car, as well as stabilizing it against lateral or longitudinal movement.” 1 In patent Figure 1, the pressurized lift gas envelope (10) contains an air ballonet (12, for adjusting airship buoyancy) and a load suspension system for carrying and distributing the weight of the gondola (11) affixed under the envelope and the thrust loads from the with attached engines. -

Manufacturing Techniques of a Hybrid Airship Prototype

UNIVERSIDADE DA BEIRA INTERIOR Engenharia Manufacturing Techniques of a Hybrid Airship Prototype Sara Emília Cruz Claro Dissertação para obtenção do Grau de Mestre em Engenharia Aeronáutica (Ciclo de estudos integrado) Orientador: Prof. Doutor Jorge Miguel Reis Silva, PhD Co-orientador: Prof. Doutor Pedro Vieira Gamboa, PhD Covilhã, outubro de 2015 ii AVISO A presente dissertação foi realizada no âmbito de um projeto de investigação desenvolvido em colaboração entre o Instituto Superior Técnico e a Universidade da Beira Interior e designado genericamente por URBLOG - Dirigível para Logística Urbana. Este projeto produziu novos conceitos aplicáveis a dirigíveis, os quais foram submetidos a processo de proteção de invenção através de um pedido de registo de patente. A equipa de inventores é constituída pelos seguintes elementos: Rosário Macário, Instituto Superior Técnico; Vasco Reis, Instituto Superior Técnico; Jorge Silva, Universidade da Beira Interior; Pedro Gamboa, Universidade da Beira Interior; João Neves, Universidade da Beira Interior. As partes da presente dissertação relevantes para efeitos do processo de proteção de invenção estão devidamente assinaladas através de chamadas de pé de página. As demais partes são da autoria do candidato, as quais foram discutidas e trabalhadas com os orientadores e o grupo de investigadores e inventores supracitados. Assim, o candidato não poderá posteriormente reclamar individualmente a autoria de qualquer das partes. Covilhã e UBI, 1 de Outubro de 2015 _______________________________ (Sara Emília Cruz Claro) iii iv Dedicator I want to dedicate this work to my family who always supported me. To my parents, for all the love, patience and strength that gave me during these five years. To my brother who never stopped believing in me, and has always been my support and my mentor. -

Luiz Otávio Furtado Ferreira Experimental Investigations of Stability and Aerodynamic Interference Effects of an X-Tail Convent

University of São Paulo São Carlos School of Engineering Mechanical Engineering Department Mechanical Engineering Graduate Program – Aircraft Luiz Otávio Furtado Ferreira Experimental investigations of stability and aerodynamic interference effects of an x-tail conventional airship São Carlos 2018 Universidade de São Paulo Escola de Engenharia de São Carlos Departamento de Engenharia Mecânica Programa de Pós-Graduação em Engenharia Mecânica – Aeronaves Luiz Otávio Furtado Ferreira Investigações experimentais de estabilidade e efeitos de interferência aerodinâmica de um dirigível convencional com cauda em x Versão Corrigida (Versão original encontra-se na unidade que aloja o Programa de Pós-Graduação) Dissertação apresentada à Escola de Engenharia de São Carlos, Universidade de São Paulo, como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Engenharia Mecânica. Área de Concentração: Aeronaves Orientador: Prof. Tit. Fernando Martini Catalano São Carlos 2018 I AUTHORIZE TOTAL OR PARTIAL REPRODUCTION OF THIS WORK BY ANY CONVENTIONAL OR ELECTRONIC MEANS, FOR RESEARCH PURPOSES, SO LONG AS THE SOURCE IS CITED. Ferreira, Luiz Otávio Furtado F383e Experimental investigations of stability and Aerodynamic interference effects of an x-tail conventional airship / Luiz Otávio Furtado Ferreira; advisor Fernando Martini Catalano. São Carlos, 2018. Master (Thesis) - Graduate Program in Mechanical Engineering and Subject area in Aircraft -- São Carlos School of Engineering, at University of São Paulo, 2018. Corrected version. 1. Airship. 2. Aerodynamic -

Autonomous Blimp Major Qualifying Project Report

Project ID: FJL-BLMP Project ID: GTH-AAA6 Towards the Realization of an Autonomous Blimp Major Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty Of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science in Electrical and Computer Engineering and Computer Science by Jeremy Colon (CS) Melinda Race (ECE) Darius Toussi (ECE) Richard Walker (ECE) Date Submitted: April 25, 2013 Project Advisors: George Heineman Fred Looft 0 Abstract This project continues an MQP from the 2011-12 academic year: Development of an Autonomous Blimp. The objective of our project was to modify the existing design by implementing autonomous flight capability using an Android phone, a power system capable of tracking energy usage, and a camera mission module for aerial photography. Through testing and flight tests, we demonstrated that we successfully implemented non-optimized autonomous flight, portions of the power system design, and a camera mission module. i Acknowledgements We would like to thank our advisors Professor George Heineman and Professor Fred Looft for their continued support throughout this project. We would also like to thank the following individuals for their help with this project: Thomas Angelotti Danielle Beaulieu Torbjorn Bergstrom Professor Stephen Bitar Adam Blumenau Nicholas DeMarinis Cathy Emmerton Richard Gammon Mitchell Monserrate Patrick Morrison Earl Ziegler ii Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... -

Kite Launch Using an Aerostat

Kite launch using an aerostat Ir. J. Breukels Delft University of Technology Faculty of Aerospace Engineering The Netherlands ________________________________________________________________________ 1 Kite launch using an aerostat Ir. J. Breukels ASSET Chair Faculty of Aerospace Engineering Delft University of Technology, the Netherlands Kluyverweg 1 2629HS Delft The Netherlands Tel: 0152585571 [email protected] Delft, August 21st 2007 ________________________________________________________________________ 2 Table of contents Table of contents 3 Nomenclature 1. Introduction 5 2. Requirements 6 2.1 Operational requirements 6 2.2 Docking and release requirements 6 2.3 Ground handling requirements 6 2.4 Safety requirements 6 2.5 Meteorological requirements 7 3. The aerostat 7 3.1 Operating the aerostat 9 3.2 Aerostatics 9 3.3 Aerodynamics 10 4. The kite release system 13 4.1 Chin docking 13 4.2 Piggy-back docking 14 5. Kite and aerostat combined 16 6. Observations during testing 16 6.1 July 25th 2007 16 6.2 July 26th 2007 17 6.3 August 14th 2007 17 6.4 August 17th 2007 17 7. Conclusions and recommendations 18 References 19 ________________________________________________________________________ 3 Nomenclature B - The upward buoyancy force acting on a body Cd - Drag coefficient Cf - Friction coefficient d - Diameter of the aerostat Df - Friction drag Dp - Preddure drag Ld - Disposable or net lift Lg - Gross or total buoyancy lift of the enclosed gas Re - Reynolds number Swetted - Wetted surface of the body V - Volume W - Total weight of the system W0 - The weight of the envelope ρa - Air density of the local atmosphere ρg - Air density of the internal gas volume ________________________________________________________________________ 4 1. -

To What Extent Does Modern Technology Address the Problems of Past

To what extent does modern technology address the problems of past airships? Ansel Sterling Barnes Today, we have numerous technologies we take for granted: electricity, easy internet access, wireless communications, vast networks of highways crossing the continents, and flights crisscrossing the globe. Flight, though, is special because it captures man’s imagination. Humankind has dreamed of flight since Paleolithic times, and has achieved it with heavier-than-air craft such as airplanes and helicopters. Both of these are very useful and have many applications, but for certain jobs, these aircraft are not the ideal option because they are loud and waste energy. Luckily, there is an alternative to energy hogs like airplanes or helicopters, a lighter-than-air craft that predates both: airships! Airships do not generate their own lift through sheer power like heavier-than-air craft. They are airborne submarines of a sort that use a different lift source: gas. They don’t need to use the force of moving air to lift them from the ground, so they require very little energy to lift off or to fly. Unfortunately, there were problems with past airships; problems that were the reason for the decline of airships after World War II: cost, pilot skill, vulnerability to weather, complex systems control, materials, size, power source, and lifting gas. This begs the question: To what extent does modern technology address the problems of past airships? With today’s technology, said problems can be managed. Most people know lighter-than-air craft by one name or another: hot air balloons, blimps, dirigibles, zeppelins, etc. -

Development of an Autonomous Blimp

Development of an Autonomous Blimp A Major Qualifying Project submitted to the faculty of Worcester Polytechnic Institute in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science April 26, 2011 Submitted by: Daniel Lanier (ME/RBE) Daniel Sarafconn (RBE) Marcus Menghini (RBE) Advised by: Professor Fred Looft Professor Stephen Nestigner Advisor Code: FJL Project Code: BLMP Abstract The purpose of this project was to design and fabricate an autonomous dirigible-based platform that could be used to enable development of navigational controllers and provide multi-mission capability through modularity. The platform was designed to carry and interface with a variety of mission specific hardware through a standard interface. A customized hardware platform was designed including a propulsion system and integrated sensor suite. Multiple ground level tests were undertaken to determine sensor performance and the capabilities of the navigational programs. Acknowledgements The team would like to thank our advisors, Professors Looft and Nestinger, for their continued support throughout this project. The team would also like to thank the following individuals for their help with the project: Richard Gammon Amy Morton Torbjorn Bergstrom Adam Sears Joe St. Germain Professor John Hall Don Pellegrino Tracy Coetzee ii Table of Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................................... ii Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................... -

Airship Aerodynamics Technical Manual

*TM 1-320 TECHNICAL MANUAL } WAR DEPARTMENT, No. 1-820 W ASHlNGTON, Pebr·um·y 11, 1941. AIRSHIP AERODYNAMICS Prepared under direction of Chief of the Air Corps SroriON I. General. Paragraph Definition of aerodynamics__________________ 1 Purpose and scope________ _____ __ __ ____ __ __ _ 2 Importance ---- ---------------------------- 3 Glossary of terms____ _____ ___ __________ __ __ 4 Types of airships----------- ---------------- 5 Aerodynamic forces_______________ __________ 6 ll. Resistance. Fluid resi&ance___________ ________ _________ 7 Shape coefficients_______ ____________________ 8 Coefficient of skin friction___________________ 9 Resistance of streamlined body-------------- 10 Prismatic coefficient------------------------ 11 Index of form efficiency_______ _____________ 12 lllustrative resistance problem_______________ 13 Scale effect--------------------------- - ---- 14 Resistance of completely rigged airship______ 15 Deceleration test --------- ------ ------------ 16 III. P ower requirements. Power required to overcome airship resistance_ 17 Results of various speed t rials____ ___ ________ 18 Burgess formula for horsepower------------- 19 Speed developed by given horsepower________ 20 Summary-----------------------""'---------- - 21 IV. Stability. Variation of pressure distribution on airship hull------------------------------------- 22 Specific stability and center of gravity of air- shiP---------------------------------- --- 23 Center of buoyancy________________________ 24 Description of major axis of airship__________ 25 -

Design a Jet-Powered Blimp (Jpb)

2015 STATE MATH AND SCIENCE COMPETITION: ENGINEERING DESIGN CHALLENGE DESIGN A JET-POWERED BLIMP (JPB) Every year, engineers build an ice-runway to provide supplies to researchers at the McMurdo Research Station in Antarctica. A sudden shift in ice floes has blocked runway access and there is a race to identify an alternate runway location. Your team has been invited to present your design for a jet-powered blimp (JPB) that can survey the icy landscape quickly and efficiently. Project Overview: You have 45 minutes to design a JPB prototype that can fly in a straight line, maintain altitude and cover long distances. You will also present the design concept and explain the propulsion system to the judges. Teams will earn points for performance (how far the JPB flies), design (the propulsion & flotation systems used), creativity, team-work and presentation skills. Awards: Five teams will win awards for performance and three teams will be recognized for team work, design and creativity. One team will receive the ‘Collier Inspired Innovation Award’ for outstanding performance and creativity. Definitions: A blimp is a non-rigid airship that relies on buoyant gases for lift and has a means of propulsion. In other words, a blimp floats using buoyant gases (like helium-filled balloons) has a way to move forward (using a motor or other propulsion system) is flexible (more like the top of a convertible car and less like the body of the car) Jet propulsion is thrust produced by passing a jet of matter (typically air or water) in the opposite direction to the direction of motion. -

The Airships

BY: Arjumand-Bano The Airships By Arjumand Bano (13005001010) Research Supervisor: Sir Kalim- Ur- Rehman A Research Project Submitted to Aviation Management In Partial fulfillment of requirement of Degree of Aviation Management Department of Institute of Aviation Studies University of Management and Technology Johar Town, Lahore May, 2017 Preface his project “The Airships” is done as a part of BS Aviation Management which has to be done in last semester in University of Management and T Technology, Lahore. I am glad to dedicate this project to Sir Kalim- Ur- Rehman which is project supervisor and without their guidance this project cannot be done competently. I am thankful to my parents and teachers who guided me in this project. For preparing the project I studied different websites related to airships. The data related to airships is easily available on internet. The research is based on airships types, its history, construction, biographies, modern airships etc. I tried my level best to put maximum information related to airships and keep the project from inaccuracies. If this project can help anyone to increase his/her information and knowledge I will feel that the purpose of my hard work has been achieved. ------------------------- Arjumand-Bano ID: 13005001010 Batch#5 Email: [email protected] BS Aviation Management (2013-2017) University of Management and Technology, Lahore. Acknowledgement t is genuine pleasure to express my deep sense of thanks and gratitude to supervisor Sir Kalim- Ur -Rehman. Their keen interest and dedication above I all their overwhelming attitude to help their students had been solely and largely responsible for completing my work. -

T.L. Blakemore Collection Lighter-Than-Air Box 1 1 Correspondence 1919-1929 2 Index: LTA Craft Photographs Vol. 1 & 2 N.D. 3

T.L. Blakemore Collection Lighter-Than-Air Box 1 1 Correspondence 1919-1929 2 Index: LTA Craft photographs Vol. 1 & 2 n.d. 3 "A" type airship n.d. 4 "AC" type airship 1922 5 "C" type airships n.d. 6 Santos Dumont - non rigid 1910 7 Car for "F" type airship (Navy) 1918 8 Goodyear Commercial motor balloon n.d. 9 "J" type airship n.d. 10 "J" type airship: Instrument board 1922 11 "J" type airship: Instrument Board n.d. 12 Photographs: J-6 engine outrigger for J-4 non-rigid 1933 13 Kite balloon: (Observation) 1920 14 Photographs Goodyear Pilgrim airship 1925 15 Photographs Roma Airship n.d. 16 Photographs RS-1 airship n.d. 17 Photographs "TC" type airship 1924 18 Photographs "TC" Instrument panels n.d. 19 Photographs "TC-11"control car n.d. 20 Photographs "TC-11" 1929 21 Photographs "TC" water model, AC Car n.d. 22 Photographs "TC" water model, TC car n.d. 23 Photographs "TC" or Los Angeles 1927 24 Photographs "TE" type airship n.d. 25 Photographs U.S. Army airship 1927 26 Photographs Zodiac 1920 27 Photograph Unidentified airship n.d. 28 Photograph Unidentified airship n.d. 29 Photograph Unidentified airship n.d. 30 Photograph Unidentified airship n.d. 31 Photograph U.S.S. Los Angeles n.d. 32 Photograph Airship car and motor n.d. 33 Photograph Airship car 1924 34 Photograph Engine car n.d. 35 Photograph Parts 1921 36 Photograph Left engine air starter 1926 37 Photograph Fabric n.d. 38 Photograph Components: Gas cell, Aero marine n.d plane & motor (docking device) 39 Photograph Mobile yaw guy winch 1933 40 Photograph Docking rail with trolley, mooring system n.d.