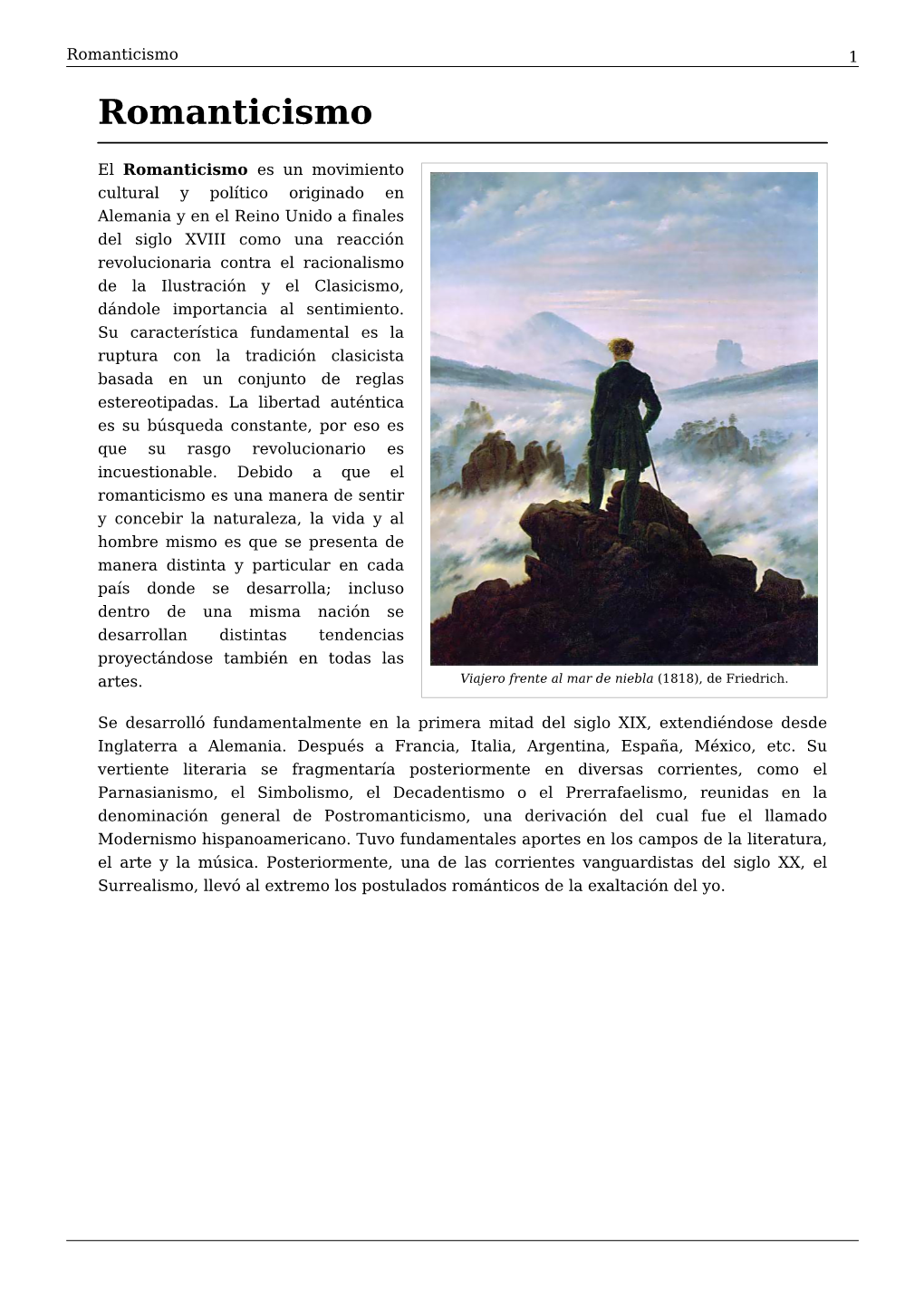

Romanticismo 1 Romanticismo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gothic Riffs Anon., the Secret Tribunal

Gothic Riffs Anon., The Secret Tribunal. courtesy of the sadleir-Black collection, University of Virginia Library Gothic Riffs Secularizing the Uncanny in the European Imaginary, 1780–1820 ) Diane Long hoeveler The OhiO STaTe UniverSiT y Press Columbus Copyright © 2010 by The Ohio State University. all rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data hoeveler, Diane Long. Gothic riffs : secularizing the uncanny in the european imaginary, 1780–1820 / Diane Long hoeveler. p. cm. includes bibliographical references and index. iSBn-13: 978-0-8142-1131-1 (cloth : alk. paper) iSBn-10: 0-8142-1131-3 (cloth : alk. paper) iSBn-13: 978-0-8142-9230-3 (cd-rom) 1. Gothic revival (Literature)—influence. 2. Gothic revival (Literature)—history and criticism. 3. Gothic fiction (Literary genre)—history and criticism. i. Title. Pn3435.h59 2010 809'.9164—dc22 2009050593 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (iSBn 978-0-8142-1131-1) CD-rOM (iSBn 978-0-8142-9230-3) Cover design by Jennifer Shoffey Forsythe. Type set in adobe Minion Pro. Printed by Thomson-Shore, inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the american national Standard for information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSi Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is for David: January 29, 2010 Riff: A simple musical phrase repeated over and over, often with a strong or syncopated rhythm, and frequently used as background to a solo improvisa- tion. —OED - c o n t e n t s - List of figures xi Preface and Acknowledgments xiii introduction Gothic Riffs: songs in the Key of secularization 1 chapter 1 Gothic Mediations: shakespeare, the sentimental, and the secularization of Virtue 35 chapter 2 Rescue operas” and Providential Deism 74 chapter 3 Ghostly Visitants: the Gothic Drama and the coexistence of immanence and transcendence 103 chapter 4 Entr’acte. -

Haunted Narratives: the Afterlife of Gothic Aesthetics in Contemporary Transatlantic Women’S Fiction

HAUNTED NARRATIVES: THE AFTERLIFE OF GOTHIC AESTHETICS IN CONTEMPORARY TRANSATLANTIC WOMEN’S FICTION Jameela F. Dallis A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Minrose Gwin Shayne A. Legassie James Coleman María DeGuzmán Ruth Salvaggio © 2016 Jameela F. Dallis ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Jameela F. Dallis: Haunted Narratives: The Afterlife of Gothic Aesthetics in Contemporary Transatlantic Women’s Fiction (Under the direction of Minrose Gwin and Shayne A. Legassie) My dissertation examines the afterlife of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Gothic aesthetics in twentieth and twenty-first century texts by women. Through close readings and attention to aesthetics and conventions that govern the Gothic, I excavate connections across nation, race, and historical period to engage critically with Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, 1959; Angela Carter’s “The Lady of the House of Love,” 1979; Shani Mootoo’s Cereus Blooms at Night, 1996; and Toni Morrison’s Love, 2003. These authors consciously employ such aesthetics to highlight and critique the power of patriarchy and imperialism, the continued exclusion of others and othered ways of knowing, loving, and being, and the consequences of oppressing, ignoring, or rebuking these peoples, realities, and systems of meaning. Such injustices bear evidence to the effects of transatlantic commerce fueled by the slave trade and the appropriation and conquering of lands and peoples that still exert a powerful oppressive force over contemporary era peoples, especially women and social minorities. -

Beyond Monk Lewis

Beyond ‘Monk’ Lewis Samuel James Simpson MA By Research University of York English and Related Literature January 2017 Abstract “What do you think of my having written in the space of ten weeks a Romance of between three and four hundred pages Octavo?”, asks Matthew Gregory Lewis to his mother.1 Contrary to the evidence—previous letters to his mother suggest the romance was a more thoughtful and time-consuming piece—Lewis was the first to feed a myth that would follow him for the rest of his life and beyond, implying he hurriedly cobbled together The Monk (1796) and that it was the product of an impulsive, immature and crude mind to be known soon after as, ‘Monk’ Lewis. The novel would stigmatise his name: he was famously criticised by Coleridge for his blasphemy, Thomas J Mathias described The Monk as a disease, calling for its censure, and The Monthly Review, for example, insisted the novel was “unfit for general circulation”.2 All these readings distract us from the intellectual and philosophic exploration of The Monk and, as Rachael Pearson observes, “overshadow…the rest of his writing career”.3 This thesis is concerned with looking beyond this idea of ‘Monk’ Lewis in three different ways which will comprise the three chapters of this thesis. The first chapter engages with The Monk’s more intellectual, philosophic borrowings of French Libertinism and how it relates to the 1790s period in which he was writing. The second chapter looks at Lewis’s dramas after The Monk and how Lewis antagonised the feared proximities of foreign influence and traditional British theatre. -

Finnegans Wake

Dickens, Ireland, and the Irish, Part II Litvack, L. (2003). Dickens, Ireland, and the Irish, Part II. The Dickensian, 99(2), 6-22. Published in: The Dickensian Document Version: Version created as part of publication process; publisher's layout; not normally made publicly available Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:27. Sep. 2021 Dickens in Finnegans Wake AARON SANTESSO ICKENS HAS NEVER BEEN A FIRST RECOURSE for explicators of Finnegans Wake. Though Joyce mentions him numerous times, DDickens has been consigned to the collector’s bin of authors whose appearances are isolated and trivial, and the resulting lack of attention means allusions to Dickens are occasionally overlooked.1 Recently, in discussing Ulysses, critics have begun to lament the underestimation of Dickens’s influence.2 Finnegans Wake supplies further evidence for the re-evaluation of Dickens’s influence on Joyce; indeed, closer attention to Dickens creates more convincing explanations of certain passages in that work. -

The Influence of Charles Robert Maturin's Melmoth the Wanderer On

University of Pardubice Faculty of Humanities Department of English and American Studies The Influence of Charles Robert Maturin’s Melmoth the Wanderer on Oscar Wilde’s Picture of Dorian Gray Bachelor Paper Author: Vladimír Hůlka Supervisor: Michael Kaylor, Ph.D. 2005 Univerzita Pardubice Fakulta humanitních studií Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky The Influence of Charles Robert Maturin’s Melmoth the Wanderer on Oscar Wilde’s Picture of Dorian Gray Vliv díla Charlese Roberta Maturina Melmoth Poutník na román Oscara Wilda Obraz Doriana Graye Bakalá řská práce Autor: Vladimír H ůlka Vedoucí: Michael Kaylor, Ph.D. 2005 Abstract: Until now the almost unconsidered influence of Charles Maturin’s Melmoth the Wanderer (1820) on Oscar Wilde’s Picture of Dorian Gray (1890/1891) is discussed. The analysis of the links between the two works is used to provide a framework for examining how Wilde uses this earlier text by a distant ancestor as a possible model for the plot and characterization of his own Decadent novel. Abstrakt: Tato práce zkoumá vliv románu Charlese Maturina Melmoth Poutník (1820) na dílo Oscara Wilda (1890/1891) Obraz Doriana Graye , vliv, který je široce uznáván, nicmén ě nebyl doposud hloub ěji analyzován. Analýza spojitostí mezi ob ěma díly je zde použita jako nástroj, umož ňující ur čit, do jaké míry a jakým zp ůsobem, Wilde použil prvky z díla svého vzdáleného p říbuzného p ři tvorb ě svého vlastního dekadentního románu Obraz Doriana Graye. Contents: 1. Oscar Wilde’s connection with Charles Robert Maturin’s work Melmoth the Wanderer ……………………………………………………………………………………...1 2. Major links between Melmoth the Wanderer and The Picture of Dorian Gray ……...…2 3. -

"Twilight Is Not Good for Maidens": Vampirism and the Insemination of Evil in Christina Rossetti's "Goblin Market"

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1987 "Twilight Is Not Good for Maidens": Vampirism and the Insemination of Evil in Christina Rossetti's "Goblin Market" David Frederick Morrill College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Morrill, David Frederick, ""Twilight Is Not Good for Maidens": Vampirism and the Insemination of Evil in Christina Rossetti's "Goblin Market"" (1987). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625393. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-fmc6-6k35 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "TWILIGHT IS NOT GOOD FOR MAIDENS": VAMPIRISM AND THE INSEMINATION OF EVIL IN CHRISTINA ROSSETTI'S GOBLIN MARKET A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by David Frederick Morrill 1987 ProQuest Number: 10627898 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Copyright by Douglas Clifton Cushing 2014

Copyright by Douglas Clifton Cushing 2014 The Thesis Committee for Douglas Clifton Cushing Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Resonances: Marcel Duchamp and the Comte de Lautréamont APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Linda Dalrymple Henderson Richard Shiff Resonances: Marcel Duchamp and the Comte de Lautréamont by Douglas Clifton Cushing, B.F.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin August 2014 Dedication In memory of Roger Cushing Jr., Madeline Cushing and Mary Lou Cavicchi, whose love, support, generosity, and encouragement led me to this place. Acknowledgements For her loving support, inspiration, and the endless conversations on the subject of Duchamp and Lautréamont that she endured, I would first like to thank my fiancée, Nicole Maloof. I would also like to thank my mother, Christine Favaloro, her husband, Joe Favaloro, and my stepfather, Leslie Cavicchi, for their confidence in me. To my advisor, Linda Dalrymple Henderson, I owe an immeasurable wealth of gratitude. Her encouragement, support, patience, and direction have been invaluable, and as a mentor she has been extraordinary. Moreover, it was in her seminar that this project began. I also offer my thanks to Richard Shiff and the other members of my thesis colloquium committee, John R. Clarke, Louis Waldman, and Alexandra Wettlaufer, for their suggestions and criticism. Thanks to Claire Howard for her additions to the research underlying this thesis, and to Willard Bohn for his help with the question of Apollinaire’s knowledge of Lautréamont. -

Nineteenth-Century British

University of Saskatchewan Department of English Ph.D. Field Examination Ph.D. candidates take this examination to establish that they have sufficient understanding to do advanced research and teaching in a specific field. Field examinations are conducted twice yearly: in October and May. At least four months before examination, students must inform the Graduate Chair in writing of their intention to sit the examination. Ph.D. students are to take this examination in May of the second year of the program or October of the third. The examination will be set and marked by three faculty specialists in the area that has been chosen by the candidate. The following lists comprise the areas in which the Department of English has set readings for Ph.D. candidates: American, Commonwealth/Postcolonial, English- Canadian, Literary Theory, Literature by Women, Medieval, Modern British, Nineteenth- Century British, Renaissance, and Restoration/Eighteenth Century. Each candidate is either to select one of the areas listed here or to propose an examination in an area for which a list is not already set. The set lists themselves are not exhaustive; each is to be taken as two-thirds of the reading to be undertaken for the examination, the final third to be drafted by the candidate in consultation with the supervisor. At least three months before examination, this list will be submitted to the candidate’s Examining Committee for approval. A candidate may choose to be examined in an area for which there is no list. Should this option be chosen, the candidate (in consultation with the supervisor) will propose an area to the Graduate Committee at least six months before the examination is to be taken. -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-13605-1 - The Cambridge Companion to British Romanticism Edited by Stuart Curran Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Companion to British Romanticism Second Edition This new edition of The Cambridge Companion to British Romanticism has been fully revised and updated and includes two wholly new essays, one on recent developments in the field and one on the rapidly expanding publishing industry of this period. It also features a comprehensive chronology and a fully up-to-date guide to further reading. For the past decade and more the Companion has been a much-admired and widely used account of the phenomenon of British Romanticism that has inspired students to look at Romantic literature from a variety of critical angles and approaches. In this new incarnation, the volume will continue to be a standard guide for students of Romantic literature and its contexts. stuart curran is Professor Emeritus of English at the University of Pennsylvania. A complete list of books in the series is at the back of this book © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-13605-1 - The Cambridge Companion to British Romanticism Edited by Stuart Curran Frontmatter More information THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO BRITISH ROMANTICISM EDITED BY STUART CURRAN © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-13605-1 - The Cambridge Companion to British Romanticism Edited by Stuart Curran Frontmatter More information cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Dubai, Tokyo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 8ru, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521136051 © Cambridge University Press 1993, 2010 This publication is in copyright. -

“Tatiana's Missing Library

Sentimental Novels and Pushkin: European Literary Markets and Russian Readers Hilde Hoogenboom Arizona State University Forthcoming, Slavic Review (Spring 2015) In 1825, Alexander Pushkin groused to another writer about the on-going proliferation of “Kotsebiatina”—a pun on “otsebiatina,” the spouting of nonsense.1 Little had changed from 1802, when Russia’s first professional writer, Nikolai Karamzin, exclaimed about the literary market: “A novel, a tale, good or bad—it is all the same, if on the title page there is the name of the famous Kotzebue.”2 Quantitative analysis of Russian book history reveals that until the 1860s, over 90% of the market for novels in Russia consisted of foreign literature in translation (the percentage would be higher could we account for foreign literature in the original). In 1802, of approximately 350 total publications in Russia, August Kotzebue (1761-1819) published fifty novels and plays in Russian; in 1825, he published 32.3 Success in the nineteenth-century literary market demanded continuous quantities of novels. In both Germany and Russia, the German sentimental novelists August Lafontaine (1758-1831) and Kotzebue, mainly a prolific playwright, reigned through the 1840s in a triumvirate with Walter Scott (1771-1832). In England, Germany, and Russia, the leading French writer was Stéphanie-Félicité, Comtesse de 1 Alexander Pushkin, Polnoe sobranie sochinenii, ed. V. D. Bonch-Bruevich and B. Tomashevskii et al. (Leningrad, 1937), 13:245. My translations appear with volume and page number in text. 2 Nikolai Karamzin, “On the Book Trade and Love of Reading in Russia,” in Selected Prose of N. M. -

Confrontation of History in Gothic Fiction Genevieve Gordon Faculty Mentor: Dr

Gordon 1 “Sins of Fathers”: Confrontation of History in Gothic Fiction Genevieve Gordon Faculty Mentor: Dr. Shelley Rees University of Science and Arts of Oklahoma The roots of the word “Gothic” are only tangentially related to the literary movement that popularized it, but its very adaptation and appropriation by 18th- and 19th-century horror authors exposes the movement’s latent tendencies. In its original sense, to be “Gothic” means to be related to the Visigoths and Ostrogoths, the now-extinct German tribes of the 4th to 6th centuries. Its first appropriation, however, was the Gothic movement in European architecture in the 12th century, characterized by flying buttresses and other ornate features. Because of these layered, referential definitions, the word “Gothic,” by the eighteenth century, was used to label a subject “obsolete, old-fashioned, or outlandish” (Clery 21). Its reference to Gothic architecture also connotes meanings of opulence and elegant antiquity, while its connection to the Visigoths and Ostrogoths, barbarous invaders of the Roman Empire, suggests an ominous threat to the very foundations of Western society. These two meanings represent a central dichotomy of Western European cultural history: barbarity versus civilization, superstition versus reason, eerie gloom versus enlightened ornament. Both of these exist simultaneously in, and consistently struggle to overtake, the historical consciousnesses of the region’s habitants. To be Gothic, then, a text looks back upon this web of historical meanings and attempts to make sense of contradictions and archaisms which threaten a coherent cultural identity. While for much of the canonical Gothic texts this meant interpreting Europe’s past, the same can be (and is) done with the history of any place, ethnicity, tradition, or people. -

Irving Massey the OMANTIC MOVEMENT: PHRASE OR FACT?*

Irving Massey THE OMANTIC MOVEMENT: PHRASE OR FACT?* THE DISPUTE OVER THE MEANING, or lack of meaning, of the word "Romanticism" has been growing in intensity during the past few years. On the one hand we have Northrop Frye and Rene Wellek, in Romanticism Reconsidered (New York and London, ~963), declaring that a stabilization of opinion has at last been achieved, and that the existence of a Romantic Movement with clearly defined features is now gen erally admitted; and a well-known journal styles itself Studies in Romanticism. At the same time, the recent Oxford History of English Literature, wary of pe:riodiza tion, tries to avoid the term. W. L. Renwick says, in Volume IX, English Liter ature 1789-1815 (Oxford, 1963), that the expression '"pre~Romanticism' is a positive hindrance" to the study of English literary history; and Ian Jack, in Volume X, English Literature 1815-1832 (Oxford, 1963), devotes fifteen pages to an attack on the word "Romanticism" itself. The day threatens to dawn when computers will be enlisted in the quarrel, and Josephine Miles, with her pioneering statistical tables, will be h~ld responsible for the dehumanization of literary history. Sitjce the scholarship on both sides of the argument is unimpeachable, it is apparent 'that the disputants' attitudes towards the problem are determined by their historiographic preferences rather than by any special information held by one school or the other. Some historians conceive of the past as a series of periods, each exhibit ing certaip distinctive features and some inner consistency; others simply feel uncom fortable when expected to classify their literary experiences in categories such as "Baroque", ''Neo-Classical", or "Romantic".