Contemporary Urbanisation in China: an Overview and the Project for Shanghai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study Away Student Handbook

NYU Shanghai STUDY AWAY STUDENT HANDBOOK Summer 2017 Shanghai Global Affairs [email protected] https://shanghai.nyu.edu/summer-admitted Table of Contents Welcome 1.Important Dates 2. Contacts 2.1 NYU Shanghai Staff and Offices Academics Global Affairs Chinese Language Clinic Student Life Ner Student Programs Student Mobility Residential Life Health and Wellness IT Services 2.2 Emergency Contacts 3. Academic Policies & Resources Academic Requirements & Registration Guidelines Courses Learning Chinese Language Academic Support Academic Advising Textbook Policy at NYU Shanghai Attendance Policy Religious Holidays and Attendance Academic Integrity Examination and Grades Policies on Examinations Makeup Examinations Grades Policies on Assigned Grades Grade of P 1 Grade of W Grade of I Incompletes Pass/Fail Option Withdrawing from a Course Program Withdrawal Tuition Refund Schedule 4. Student Life Policies & Resources Student Conduct Policies and Process Residential Life Residence Hall Policies Resource Center How to Submit a Facilities Work Order Fitness Center Health and Wellness Health Insurance 5. Arriving in Shanghai Arrival Information Transportation to NYU Shanghai Shanghai Airports and Railway Stations Traveling from the Airport Move-In Day Arrangement Move-In Day 6. Life in Shanghai Arranging Your Finance Living Cost in Shanghai Banking and ATMs Exchanging Money Getting Around Dining Shopping Language Tips Religious Services Shanghai Attractions 2 Travel 7. Information Technology (IT) Printing IT FAQ – Setup VPN 8. Be Safe Public Safety Crime Prevention Safety in Shanghai Emergency Medical Transport NYU Shanghai Card Services Lost and Found Services Shuttle bus Safety Tips Safety on Campus Regulations Tips for Pickpocket Prevention If You Already Have Been Pickpocketed Information alert 3 Welcome On behalf of the entire NYU Shanghai team, congratulations on your acceptance to NYU Shanghai’s Summer Program. -

Heng Feng Road, Zhabei District, Shanghai, China

Heng Feng Road, Zhabei District, Shanghai, China View this office online at: https://www.newofficeasia.com/details/offices-heng-feng-road-zhabei-district- shanghai This fully serviced business centre is in a great location within a premium office building offering spectacular views of the Su Zhou Creek. There's a comprehensive package of services available for clients, including IT support, accounting assistance and business licencing. There are conference rooms available, a telephone answering service and other types of administrative support, all from a highly convenient town centre location offering 24 hour access, security system and plenty of car parking spaces. Transport links Nearest tube: Metro Line 1, Han Zhong Road Station Nearest railway station: Shanghai Railway Station Nearest road: Metro Line 1, Han Zhong Road Station Nearest airport: Metro Line 1, Han Zhong Road Station Key features 24 hour access Access to multiple centres nation-wide Administrative support Car parking spaces Close to railway station Conference rooms Conference rooms High speed internet IT support available Meeting rooms Modern interiors Near to subway / underground station Reception staff Security system Telephone answering service Town centre location Location This business centre is in a great location in the central business district amongst the hub of public transportation choices. It's only 50 metres from Subway Line 1, alongside Huaihai Road and Nanjing Road and Shanghai Railway Station is also easily accessible. Points of interest within 1000 metres Hanzhong -

Enchanting Hospitality

enchanting hospitality The Langham, Shanghai, Xintiandi is located at the gateway to the vibrant Xintiandi entertainment area surrounded by fashionable dining, luxury retail shopping and also adjacent to key businesses situated along Huai Hai Road. The Hotel offers enchanting hospitality in an ambience of modern luxury and elegance along with up-to-date technology suitable for both business and leisure travellers. refreshing accommodation Since 1865, exceptional service, luxury and innovative design have been the hallmarks of the Langham legacy. Those traditions continue today at The Langham, Shanghai, Xintiandi. The luxurious rooms feature the following amenities: Signature Blissful Bed Floor to ceiling windows Wired and wireless broadband Nespresso coffee machine and mini bar Internet access 2 washbasins with adjustable mirrors 40” LCD television Electric toilet Smart phone docking station Separate rain shower Iron and ironing board Heated bathroom floor Room Type No.of Rooms Size(sqm) Size(sqft) Superior Room 126 40 430 Deluxe Room 117 40~43 430~460 Deluxe Studio 9 48 515 Executive Room* 54 40 430 Executive Studio* 10 48 515 Junior Suite* 19 55 590 One Bedroom Suite* 18 55 590 Executive Suite* 2 90 970 Presidential Suite*(duplex) 1 180 1,940 Chairman Suite*(duplex) 1 345 3,715 Total 357 - - the langham club Located on Level 27, The Langham Club offers an intimate Club Lounge experience for guests looking to relax or catch up on the day’s business. Guests staying in Club guestrooms and suites can enjoy complimentary access to The -

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction The name Shanghai still conjures images of romance, mystery and adventure, but for decades it was an austere backwater. After the success of Mao Zedong's communist revolution in 1949, the authorities clamped down hard on Shanghai, castigating China's second city for its prewar status as a playground of gangsters and colonial adventurers. And so it was. In its heyday, the 1920s and '30s, cosmopolitan Shanghai was a dynamic melting pot for people, ideas and money from all over the planet. Business boomed, fortunes were made, and everything seemed possible. It was a time of breakneck industrial progress, swaggering confidence and smoky jazz venues. Thanks to economic reforms implemented in the 1980s by Deng Xiaoping, Shanghai's commercial potential has reemerged and is flourishing again. Stand today on the historic Bund and look across the Huangpu River. The soaring 1,614-ft/492-m Shanghai World Financial Center tower looms over the ambitious skyline of the Pudong financial district. Alongside it are other key landmarks: the glittering, 88- story Jinmao Building; the rocket-shaped Oriental Pearl TV Tower; and the Shanghai Stock Exchange. The 128-story Shanghai Tower is the tallest building in China (and, after the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, the second-tallest in the world). Glass-and-steel skyscrapers reach for the clouds, Mercedes sedans cruise the neon-lit streets, luxury- brand boutiques stock all the stylish trappings available in New York, and the restaurant, bar and clubbing scene pulsates with an energy all its own. Perhaps more than any other city in Asia, Shanghai has the confidence and sheer determination to forge a glittering future as one of the world's most important commercial centers. -

Transportation the Conference Will Be Held in North Zhongshan Road

Transportation The conference will be held in North Zhongshan Road campus of East China Normal University (ECNU). The address is: No. 3663, North Zhongshan Road, Putuo, Shanghai. The hotel where all participants will stay is Yifu Building (逸夫楼) located on the campus. Arrival by flights: There are two airports in Shanghai: the Pudong Airport in east Shanghai and the Hongqiao Airport in west Shanghai. Both are convenient to get to the North Zhongshan Road campus of ECNU. At the airport, you can take taxi or metro to North Zhongshan Road Campus of ECNU. Taxi is recommended in terms of its convenience and time saving. Our students will be there for helping you to find the taxi. By taxi From Pudong Airport: about one hour and 200 CNY when traffic is not busy. From Hongqiao Airport: about 30 minutes and 60 CNY when traffic is not busy. Please print the following tips if you like “请带我去华东师范大学中山北路校区正门” in advance and show it to the taxi driver. The Chinese words in tips mean "Please take me to the main gate of North Zhongshan Road Campus of ECNU". By metro From Pudong Airport: 1. Metro Line 2 (6:00 - 22:00)->Zhongshan Park (中山公园) station (Note: exchange at Guanglan Road station(广兰路)), then take taxi for about 10 minutes and 14 CNY cost to North Zhongshan Road Campus of ECNU, or take the bus 67 for 2 stops and get off at ECNU station(华东师大站)instead. 2. Metro Line 2->Jiangsu Road (江苏路) station-> Metro Line 11->Longde Road (隆德路) station->Metro Line 13-> Jinshajiang Road (金沙江路) Station->10 minutes walk. -

Development of High-Speed Rail in the People's Republic of China

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Haixiao, Pan; Ya, Gao Working Paper Development of high-speed rail in the People's Republic of China ADBI Working Paper Series, No. 959 Provided in Cooperation with: Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI), Tokyo Suggested Citation: Haixiao, Pan; Ya, Gao (2019) : Development of high-speed rail in the People's Republic of China, ADBI Working Paper Series, No. 959, Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI), Tokyo This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/222726 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/igo/ www.econstor.eu ADBI Working Paper Series DEVELOPMENT OF HIGH-SPEED RAIL IN THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA Pan Haixiao and Gao Ya No. -

Transportation Information for Tour in Shanghai

China Business Engine 商擎网 Transportation Information for Tour in Shanghai Choice No.1: Shanghai Tourist Distribution Center Shanghai Tourist Distribution Center is the only tourist distribution spot with the function of tourist supermarket. The self-organized model for tourism of the center is the most suitable choice for tourists who want to enjoy self-organized trip with convenient transportation service. If you book the tickets or self-organized trip, you may simply go to branch center near your place and take the bus to your destination, and then take the bus home from the tourism spot at the regulated time. You can book the ticket through the website, phone call or even buy the ticket after you are on the bus. There are altogether 5 distribution stations of Shanghai Tourist Distribution Center: Shanghai Indoor Stadium Station Kongkou Station Yangpu Station Huangpu Station Shanghai Circus World Station Choice No.2: Shanghai Sightseeing Bus There are altogether 10 lines for sightseeing buses covering most of the sight spots in Shanghai. For detailed information please consult (http://ourtour.com.cn/txdestination/traffic_art_detail-id_482.html) Choice No.3: Public transportation Public transportation is quite convenient for tour in Shanghai. There are all together 9 subway lines throughout Shanghai connecting most of the downtown districts, and many stations of the subway lines are the tourism spots at the same time. The buses run in nearly every street in Shanghai. Useful subway lines and stations for tourism: Line 1: Shanghai Railway Station, People’s Square, South Huangpi Road (Xintiandi), Hengshan Road, Xujiahui, Shanghai Indoor Stadium, Shanghai South Railway Station, Jin Jiang Amusement Park Line 2: Zhongshan Park, Jingan Temple, Lujiazui, Shanghai Science and Technology Museum, Shanghai Century Park Line 3: Hongkou Football Stadium, Shanghai Railway Station, Shanghai South Railway Station Choice No.4: Taxi It is the most convenient transportation tool for you to choose for sightseeing in downtown area of Shanghai. -

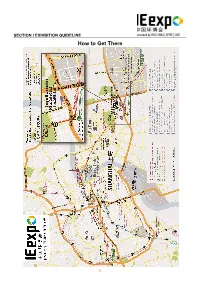

How to Get There

SECTION I EXHIBITION GUIDELINE How to Get There 12 SECTION I EXHIBITION GUIDELINE How to Get There (cont’d) Shanghai Metro Map 13 SECTION I EXHIBITION GUIDELINE How to Get There (cont’d) SNIEC is strategically located in Pudong‘s key economic development zone. There is a public traffic interchange for bus and metro, , one named “Longyang Road Station“ about 10-min walk from the station to fairground, and one named “Huamu Road Station“ about 1-min walk from the station to fairground. By flight The expo centre is located half way between Pudong International Airport and Hongqiao Airport, 35 km away from Pudong International Airport to the east, and 32 km away from Hongqiao Airport to the west. You can take the airport bus, maglev or metro directly to the expo center. From Pudong International Airport By taxi By Transrapid Maglev: from Pudong International Airport to Longyang Road Take metro line 2 to Longyang Road Station to change line 7 to Huamu Road Station, 60 min. By Airport Line Bus No. 3: from Pudong Int’l Airport to Longyang Road, 40 min, ca. RMB 20. From Hongqiao Airport By taxi Take metro line 2 to Longyang Road Station to change line 7 to Huamu Road Station, 60 min. By train From Shanghai Railway Station or Shanghai South Railway Station please take metro line1 to People’s Square, then take metro line 2 toward Pudong International Airport Station and get off at Longyang Road Station to change line7 to Huamu Road Station. From Hongqiao Railway Station, please take metro line 2 to Longyang Road Station and change line 7 to Huamu Road Station. -

Travel Pocket Guide

10 – 13 October 2019 Shanghai New International Expo Centre Travel Pocket Guide Music China 2019 (10 – 13 October) Content General fair information ......................................................................................................... 2 Value-for-money hotels .......................................................................................................... 3 Attractions .............................................................................................................................. 4 Restaurants / Pubs ................................................................................................................. 7 Useful phrases ........................................................................................................................ 9 Useful websites .................................................................................................................... 10 Page 1 Music China 2019 (10 – 13 October) General fair information Music China 2018 (10 – 13 October 2018) Venue: Shanghai New International Expo Centre (SNIEC) 2345 Long Yang Road, Pudong Area, Shanghai 201204, China 上海新国际博览中心 中国上海市浦东新区龙阳路 2345 号 邮编: 201204 Opening hours: 10 October 2019 9:30am – 5:00pm 11 October 2019 9:30am – 5:00pm 12 October 2019 9:30am – 5:00pm 13 October 2019 9:30am – 3:30pm How to get to the fairground 1) Metro Line 7 to Hua Mu Road Station , the station is located next to SNIEC fairground / 2) Get off at Long Yang Road Station (an interchange station for bus, metro and maglev), it takes about -

22/F, Zhabei Centro, No. 568 Hengfeng Road, Zhabei District, Shanghai, China

22/F, Zhabei Centro, No. 568 Hengfeng Road, Zhabei District, Shanghai, China View this office online at: https://www.newofficeasia.com/details/serviced-offices-zhabei-centro-no-568- hengfeng-road-district-shanghai-china This business centre resides on the 22nd floor of this magnificent building which radiates architectural genius while providing spectacular views across the Zhabei District. Companies can enjoy round the clock access to offices which offer broadband internet and plenty of light for a productive working environment. Stylish meeting and conferences rooms are available, providing comprehensive videoconferencing facilities and a comfortable lounge for hosting informal business discussions afterwards. With an on-site restaurant, this building presents convenient accommodation which is offered under flexible terms, allowing businesses to expand or contract without the hassle of long-term commitments. Transport links Nearest tube: Hanzhong Road Nearest railway station: Shanghai Railway Station Nearest airport: Hanzhong Road Key features 24 hour access 24-hour security Access to multiple centres nation-wide Access to multiple centres world-wide Car parking spaces Central heating Comfortable lounge Conference rooms Flexible contracts High-speed internet Hot desking Meeting rooms Photocopying available Restaurant in the building Town centre location Video conference facilities Virtual office available WC (separate male & female) Location Situated on Hengfeng Road, this business centre resides within the popular Zhabei District which has plenty to offer developing businesses. Wusong River runs close by and the surrounding area is home to variety of fine hotels including The Grand Mercure and InterContinental Shanghai Puxi hotel in addition to supermarkets and the Zhabei District government. This centre boasts connectivity with bus routes and metro lines 1, 3 and 4 all within easy walking distance while Shanghai Railway Station is just a short stroll away, providing high-speed train services to the major cities in China. -

Development of High-Speed Rail in the People's Republic of China

ADBI Working Paper Series DEVELOPMENT OF HIGH-SPEED RAIL IN THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA Pan Haixiao and Gao Ya No. 959 May 2019 Asian Development Bank Institute Pan Haixiao is a professor at the Department of Urban Planning of Tongji University. Gao Ya is a PhD candidate at the Department of Urban Planning of Tongji University. The views expressed in this paper are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of ADBI, ADB, its Board of Directors, or the governments they represent. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this paper and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. Terminology used may not necessarily be consistent with ADB official terms. Working papers are subject to formal revision and correction before they are finalized and considered published. The Working Paper series is a continuation of the formerly named Discussion Paper series; the numbering of the papers continued without interruption or change. ADBI’s working papers reflect initial ideas on a topic and are posted online for discussion. Some working papers may develop into other forms of publication. Suggested citation: Haixiao, P. and G. Ya. 2019. Development of High-Speed Rail in the People’s Republic of China. ADBI Working Paper 959. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute. Available: https://www.adb.org/publications/development-high-speed-rail-prc Please contact the authors for information about this paper. Email: [email protected] Asian Development Bank Institute Kasumigaseki Building, 8th Floor 3-2-5 Kasumigaseki, Chiyoda-ku Tokyo 100-6008, Japan Tel: +81-3-3593-5500 Fax: +81-3-3593-5571 URL: www.adbi.org E-mail: [email protected] © 2019 Asian Development Bank Institute ADBI Working Paper 959 Haixiao and Ya Abstract High-speed rail (HSR) construction is continuing at a rapid pace in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) to improve rail’s competitiveness in the passenger market and facilitate inter-city accessibility. -

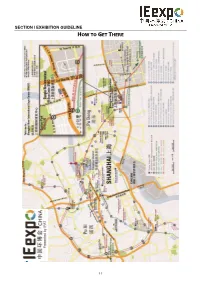

How to Get There

SECTION I EXHIBITION GUIDELINE HOW TO GET THERE 11 SECTION I EXHIBITION GUIDELINE HOW TO GET THERE (CONT’D) SHANGHAI METRO MAP 12 SECTION I EXHIBITION GUIDELINE HOW TO GET THERE (CONT’D) SNIEC is strategically located in Pudong‘s key economic development zone. There is a public traffic interchange for bus and metro, , one named “Longyang Road Station“ about 10-min walk from the station to fairground, and one named “Huamu Road Station“ about 1-min walk from the station to fairground. By flight The expo centre is located half way between Pudong International Airport and Hongqiao Airport, 35 km away from Pudong International Airport to the east, and 32 km away from Hongqiao Airport to the west. You can take the airport bus, maglev or metro directly to the expo center. From Pudong International Airport By taxi By Transrapid Maglev: from Pudong International Airport to Longyang Road Take metro line 2 to Longyang Road Station to change line 7 to Huamu Road Station, 100 min. By Airport Line Bus No. 3: from Pudong Int’l Airport to Longyang Road, 40 min, ca. RMB 20. From Hongqiao Airport By taxi Take metro line 2 to Longyang Road Station to change line 7 to Huamu Road Station, 60 min. By train From Shanghai Railway Station or Shanghai South Railway Station please take metro line1 to People’s Square, then take metro line 2 toward Pudong International Airport Station and get off at Longyang Road Station to change line7 to Huamu Road Station. From Hongqiao Railway Station, please take metro line 2 to Longyang Road Station and change line 7 to Huamu Road Station.