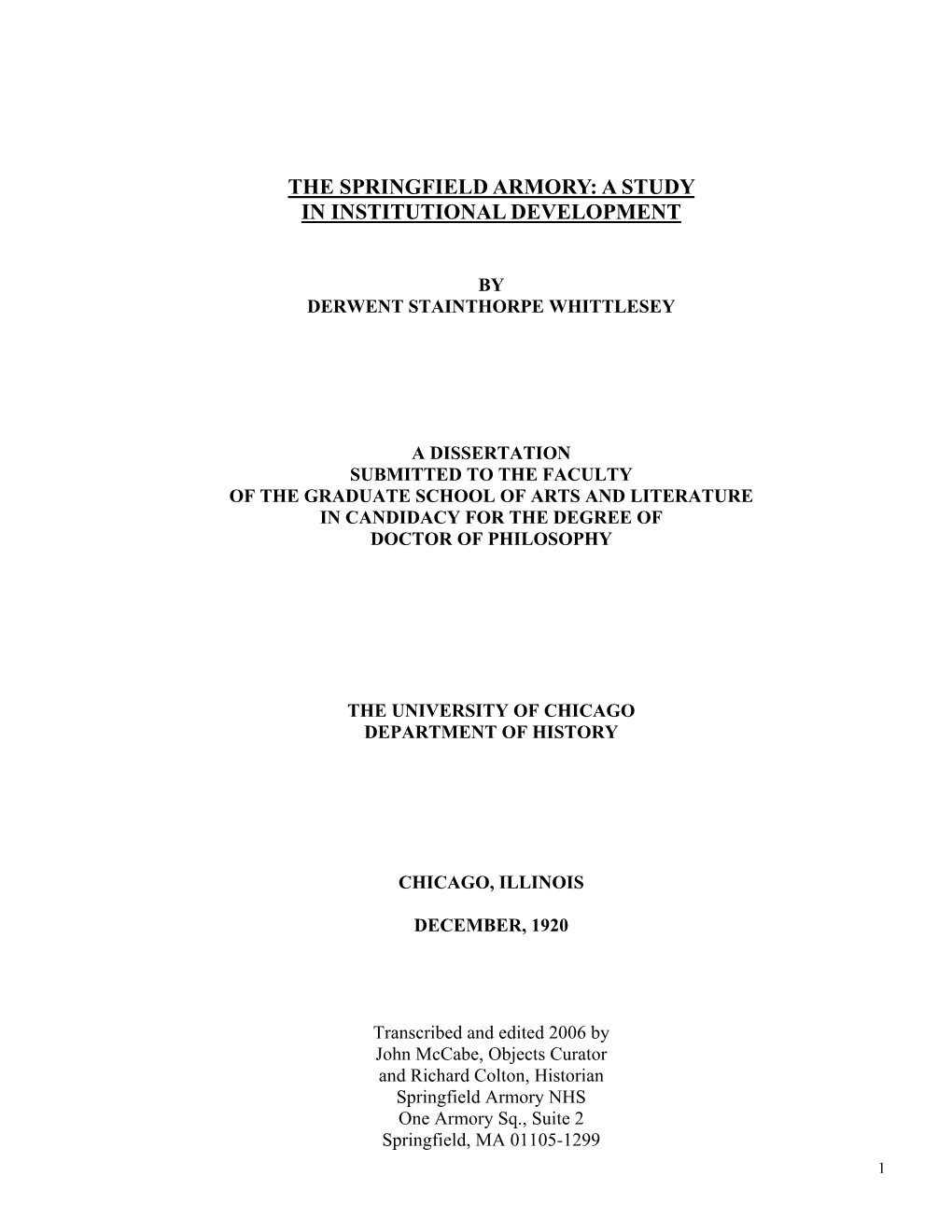

The Springfield Armory: a Study in Institutional Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

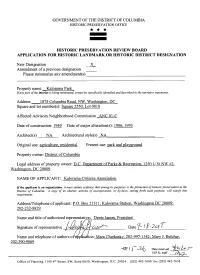

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: __Kalorama Park____________________________________________ Other names/site number: Little, John, Estate of; Kalorama Park Archaeological Site, 51NW061 Name of related multiple property listing: __N/A_________________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: __1875 Columbia Road, NW City or town: ___Washington_________ State: _DC___________ County: ____________ Not For Publication: Vicinity: ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering -

Popular Sovereignty, Slavery in the Territories, and the South, 1785-1860

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 Popular sovereignty, slavery in the territories, and the South, 1785-1860 Robert Christopher Childers Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Childers, Robert Christopher, "Popular sovereignty, slavery in the territories, and the South, 1785-1860" (2010). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1135. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1135 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. POPULAR SOVEREIGNTY, SLAVERY IN THE TERRITORIES, AND THE SOUTH, 1785-1860 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Robert Christopher Childers B.S., B.S.E., Emporia State University, 2002 M.A., Emporia State University, 2004 May 2010 For my wife ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Writing history might seem a solitary task, but in truth it is a collaborative effort. Throughout my experience working on this project, I have engaged with fellow scholars whose help has made my work possible. Numerous archivists aided me in the search for sources. Working in the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill gave me access to the letters and writings of southern leaders and common people alike. -

Modern Trend of Country Made/Improvised Pistols Used In

orensi f F c R o e l s a e n r a r u c Waghmare et al. J Forensic Res 2012, S1 o h J Journal of Forensic Research DOI: 10.4172/2157-7145.S1-003 ISSN: 2157-7145 Research Article Open Access Modern Trend of Country Made /Improvised Pistols Used in the Capital of India Waghmare NP*, Suresh R, Puri P ,Varshney KC, Anand V, Kompal and Anubha Lal Forensic Science Laboratory, NCT of Delhi, Madhuban Chowk, Sector-14, Delhi-110085, India Abstract Now a days crimes relating to firearms and ammunition have dramatically increased in northern part of India. It has been observed that Country made pistols of 8mm/.315” bore; Improvised pistols of 7.65mm/9mm calibre, .32”/.38” calibre are randomly used by criminals in Delhi and NCR regions. On the basis of crime cases received in the Forensic Science Laboratory for examination, the smooth bore illegal country made firearms chambered for pistol, revolver and rifle cartridges are very often encountered in criminal cases all over India and other developing countries. The possibility of identifying types of smooth bore firearms of country made and improvised pistols has been studied. On analysis of crime cases received for forensic examination, it has been found that 75% crimes are committing by 8mm/.315” calibre by country made pistols, 20% by 7.65mm calibre/bore improvised pistols and remaining 5% crime by other firearms like 12 bore country made pistol, .32”/.38” calibre/bore improvised pistols. In present study, firearms details relating to length of barrel, total length of firearms, internal diameter of barrel at muzzle end and breech end have been studied in view of forensic significance and may be useful for Forensic scientists, Law Enforcement Agencies, Police Officers and Judicial Officers etc. -

The Springfield Armory Historic Background

The Springfield Armory Historic Background Report by Todd Jones, Historic Preservation Specialist Federal Emergency Management Agency October 2011 The Springfield Armory Exceptionally unique among the structures in Springfield, MA, the Springfield Armory has stood on Howard Street for over one hundred years. Yet, with its impressive medieval architecture, the building could easily pass for a centuries-old European castle. It may appear as a much unexpected feature on the skyline of a Connecticut River Valley city, but considering Springfield’s illustrious history as a manufacturer of war goods, a castle is actually quite an appropriate inclusion. The Armory is located today at 29 Howard Street. It is surrounded by a dense urban community characterized by commercial interests, with parking lots, a strip mall, and an apartment block included as its primary neighbors. The area transitioned from an urban working class residential neighborhood to its present commercial character during the mid and late twentieth century. Figure 1: Location of the State Armory in Springfield, 29 Howard Street, Springfield, Hampden County, Massachusetts (42.10144, -72.60216).1 Figure 2: Topographic map of Springfield showing the location of the State Armory.2 1 http://mapper.acme.com, accessed September 22, 2011 2 http://mapper.acme.com, accessed September 22, 2011. ______________________________________________________________________________ Attachment A. Historic Background Page 2 The 1895 Armory The structure was finished in 1895 for the Massachusetts Volunteer Militia (MVM), referred to in modern times as the Massachusetts National Guard. It was designed by the Boston architectural firm of Wait & Cutter, led by Robert Wait and Amos Cutter, who also planned the Fall River Armory at the same time. -

The Spirit of the Heights Thomas H. O'connor

THE SPIRIT OF THE HEIGHTS THOMAS H. O’CONNOR university historian to An e-book published by Linden Lane Press at Boston College. THE SPIRIT OF THE HEIGHTS THOMAS H. O’CONNOR university historian Linden Lane Press at Boston College Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts Linden Lane Press at Boston College 140 Commonwealth Avenue 3 Lake Street Building Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts 02467 617–552–4820 www.bc.edu/lindenlanepress Copyright © 2011 by The Trustees of Boston College All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage or retrieval) without the permission of the publisher. Printed in the USA ii contents preface d Thomas H. O’Connor v Dancing Under the Towers 22 Dante Revisited 23 a “Dean’s List” 23 AHANA 1 Devlin Hall 24 Alpha Sigma Nu 2 Donovan, Charles F., S.J. 25 Alumni 2 Dustbowl 25 AMDG 3 Archangel Michael 4 e Architects 4 Eagle 27 Equestrian Club 28 b Bands 5 f Bapst Library 6 Faith on Campus 29 Beanpot Tournament 7 Fine Arts 30 Bells of Gasson 7 Flutie, Doug 31 Black Talent Program 8 Flying Club 31 Boston “College” 9 Ford Tower 32 Boston College at War 9 Fulbright Awards 32 Boston College Club 10 Fulton Debating Society 33 Bourneuf House 11 Fundraising 33 Brighton Campus 11 Bronze Eagle 12 g Burns Library 13 Gasson Hall 35 Goldfish Craze 36 c Cadets 14 h Candlemas Lectures 15 Hancock House 37 Carney, Andrew 15 Heartbreak Hill 38 Cavanaugh, Frank 16 The Heights 38 Charter 17 Hockey 39 Chuckin’ Charlie 17 Houston Awards 40 Church in the 21st Century 18 Humanities Series 40 Class of 1913 18 Cocoanut Grove 19 i Commencement, First 20 Ignatius of Loyola 41 Conte Forum 20 Intown College 42 Cross & Crown 21 Irish Hall of Fame 43 iii contents Irish Room 43 r Irish Studies 44 Ratio Studiorum 62 RecPlex 63 k Red Cross Club 63 Kennedy, John Fitzgerald 45 Reservoir Land 63 Retired Faculty Association 64 l Labyrinth 46 s Law School 47 Saints in Marble 65 Lawrence Farm 47 Seal of Boston College 66 Linden Lane 48 Shaw, Joseph Coolidge, S.J. -

HISTORICAL FIREARMS - CONSTRUCTION KIT - DATA SHEET Firearms FILENAME DESCRIPTION Cannon 4 Gauge Steel 0M.Wav CANNON STEEL 4 Gauge

Historical HISTORICAL FIREARMS - CONSTRUCTION KIT - DATA SHEET Firearms FILENAME DESCRIPTION Cannon 4 Gauge Steel 0m.wav CANNON STEEL 4 gauge. Fired in stone pit into open landscape. Microphone attached to cannon. 6 Shots. Cannon 4 Gauge Steel 25m.wav CANNON STEEL 4 gauge. Fired in stone pit into open landscape. A/B omni directional microphones in medium distance. 6 Cannon 4 Gauge Steel 15m.wav CANNON STEEL 4 gauge. Fired in stone pit into open landscape. A/B hyper cardioidd microphone in medium distance, pointing towards muzzle. 6 Cannon 4 Gauge Steel 3m.wav CANNON STEEL 4 gauge. Fired in stone pit into open landscape. Flanking shooter left and right, omnidirectional microphones, close. 6 Cannon 4 Gauge Steel 5m Rear.wav CANNON STEEL 4 gauge. Fired in stone pit into open landscape. XY cardioid microphones, medium distance behind shooter, pointing in shooting direction. 6 Cannon 4 Gauge Steel 75m.wav CANNON STEEL 4 gauge. Fired in stone pit into open landscape. Mono omnidirectional large diaphragm microphone, close to bullet impact spot. 6 Cannon 4 Gauge Steel 100m A.wav CANNON STEEL 4 gauge. Fired in stone pit into open landscape. Mono omnidirectional microphone, far distance, left side. 6 Cannon 4 Gauge Steel 100m B.wav CANNON STEEL 4 gauge. Fired in stone pit into open landscape. Mono omnidirectional microphone, far distance, right side. 6 Cannon 4 Gauge Steel 30m Indirect.wav CANNON STEEL 4 gauge. Fired in stone pit into open landscape. Mono shotgun microphone, medium distance, pointing away from gun into forest. 6 Cannon 4 Gauge Steel 25m Rear.wav CANNON STEEL 4 gauge. -

V\Oc^Rn Weapons

THE IRISH VOLUNTEER. 11 (3) Slowness of firing consequent upon RIFLES AS MILITARY IV E A PONS. ihe Iwp preceding difliculitvs. The loading diff cultiea were tmiter ally The progress of '.he rifle ns a military reduced by the invention of the G ret tier weapon will be made clear by a few le.vi- Min e expanding bullet. This bullet mis ing events and dale;.,* made- small enough to pass down the bar 11100—A number of rifles -ssned to Dan rel just as with the smooth bore. The Ish troops. /v\oc^ rn Weapons bass ol 1he hit lief was made hollow nitd 1(431 — Landgrave cf Hr had i-uo had fitted to Ijl a copper or iron plug or troop of tiflctneit. cap. When the p ece was fired ihe gases' ffill — IJavaria had .r,r-vera1 troops of drove this wedge into tbe bullet and ex _ riflemen, ... OF ... * panded- it to fit! the rifling. TVs bul 1(570- Rifles issued to 3on:r of ihe let was invented ! 83.31850. I Tench troops. IV.th the breechloader the bullet is 1775—Rifles used in tile A m eren War made the lull bote of the barret, iochiJ- ^ o f. Independence. itig the depth of the grooves. This is I7W3—Rifles issuer 1 to French troepa hy possible .tg the cartridge chamber is lar the Republic; wilhdrawn by ger in diameter than the bore of the bar Napoleon a* inefficient. Warfare rel, nnd the force of the explosion drives 1800—Baker's rifle issued to a ferf the bullet into the rifling. -

Inventory of the Grimke Family Papers, 1678-1977, Circa 1990S

Inventory of the Grimke Family Papers, 1678-1977, circa 1990s Addlestone Library, Special Collections College of Charleston 66 George Street Charleston, SC 29424 USA http://archives.library.cofc.edu Phone: (843) 953-8016 | Fax: (843) 953-6319 Table of Contents Descriptive Summary................................................................................................................ 3 Biographical and Historical Note...............................................................................................3 Collection Overview...................................................................................................................4 Restrictions................................................................................................................................ 5 Search Terms............................................................................................................................6 Related Material........................................................................................................................ 6 Administrative Information......................................................................................................... 7 Detailed Description of the Collection.......................................................................................8 John Paul Grimke letters (generation 1)........................................................................... 8 John F. and Mary Grimke correspondence (generation 2)................................................8 -

Sample Pages

Introduction and Study Guide This is the first edition of Speakers of the House of Representatives 1789 - 2009. With infor- mation that has never before been gathered into one volume, it not only includes detailed biographies of the 53 men and woman who have served as Speaker, but offers a wealth of supportive material that combines for a complete picture of the Speakers and the speaker- ship - the history, the power, and the changes. With detailed content, thoughtful arrangement, and several “user guide” elements, Speakers of the House of Representatives is designed for multiple levels of study. CONTENT Speaker Biographies This major portion of the work - comprises 54 detailed biographies that average 7 pages long. This section is arranged chronologically, beginning with the first Speaker — Frederick Muhlenberg, who began his term in 1789 - and ending with the current Speaker - Nancy Pelosi, who was elected in 2007 as the first female Speaker of the House. Each biography starts off with an image of the Speaker and dates of service, and thoughtfully categorized into logical subsections that guide the reader through the details: Personal History; Early Years in Congress; The Vote; Acceptance Speech; Legacy as Speaker; After Leaving the Speakership. Each biography is strengthened by direct quotations — easily identified in italics — of the Speaker, or influential colleagues of the time. In addition, scattered throughout the bio- graphical section are unique, original graphics - from autographs to personal letters - that not only give the reader an inside look at the Speaker, but also at the times during which he served. Biographies also include Further Reading, and cross references to Primary Docu- ments that appear later in the book. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Wood, Christopher Were the developments in 19th century small arms due to new concepts by the inventors and innovators in the fields, or were they in fact existing concepts made possible by the advances of the industrial revolution? Original Citation Wood, Christopher (2013) Were the developments in 19th century small arms due to new concepts by the inventors and innovators in the fields, or were they in fact existing concepts made possible by the advances of the industrial revolution? Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/19501/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Were the developments in 19th century small -

Metropolitan Boston Downtown Boston

WELCOME TO MASSACHUSETTS! CONTACT INFORMATION REGIONAL TOURISM COUNCILS STATE ROAD LAWS NONRESIDENT PRIVILEGES Massachusetts grants the same privileges EMERGENCY ASSISTANCE Fire, Police, Ambulance: 911 16 to nonresidents as to Massachusetts residents. On behalf of the Commonwealth, MBTA PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION 2 welcome to Massachusetts. In our MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION 10 SPEED LAW Observe posted speed limits. The runs daily service on buses, trains, trolleys and ferries 14 3 great state, you can enjoy the rolling Official Transportation Map 15 HAZARDOUS CARGO All hazardous cargo (HC) and cargo tankers General Information throughout Boston and surrounding towns. Stations can be identified 13 hills of the west and in under three by a black on a white, circular sign. Pay your fare with a 9 1 are prohibited from the Boston Tunnels. hours travel east to visit our pristine MassDOT Headquarters 857-368-4636 11 reusable, rechargeable CharlieCard (plastic) or CharlieTicket 12 DRUNK DRIVING LAWS Massachusetts enforces these laws rigorously. beaches. You will find a state full (toll free) 877-623-6846 (paper) that can be purchased at over 500 fare-vending machines 1. Greater Boston 9. MetroWest 4 MOBILE ELECTRONIC DEVICE LAWS Operators cannot use any of history and rich in diversity that (TTY) 857-368-0655 located at all subway stations and Logan airport terminals. At street- 2. North of Boston 10. Johnny Appleseed Trail 5 3. Greater Merrimack Valley 11. Central Massachusetts mobile electronic device to write, send, or read an electronic opens its doors to millions of visitors www.mass.gov/massdot level stations and local bus stops you pay on board. -

4-H Shooting Sports an Introduction to Muzzleloading Firearms

4-H Shooting Sports An Introduction to Muzzleloading Firearms A buckskin-clad hunter in a skunk skin hat slips quickly along a woodland trail. Suddenly he freezes, shoulders his flintlock rifle, and fires. As the cloud of white smoke clears, he notes the bullet has hit well. No, he’s not a frontiersman of long ago; he is a member of an emerging group of modern shooters and hunters— those who prefer to use muzzleloading firearms in the pursuit of their sport. American history is deeply intertwined with the development of firearms, and improved muzzleloading arms were key elements in the nation’s develop - ment. The West, land west of the Appalachian Mountains, was opened by hardy frontiersmen carrying Kentucky (or Pennsylvania) rifles. Their long, light, and accurate rifles were adequate when wildlife up to the size of white-tailed deer and bears were staples of the frontier diet. Those rifles were inadequate for the Louisiana expedition led by Lewis and Clark. Bison and grizzly bears required heavier loads with larger bullets, and horseback travel made a shorter rifle desir - able. The Hawken plains rifle answered that need and served the mountainmen who explored the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains. Only when breechloading arms were developed in the middle of the 19th cen - tury did muzzleloaders begin to decline. The superior loading speed and conven - ience of the breechloader made them more desirable. Now, a century later, shoot - ers are rediscovering muzzleloading arms—reliving history and having fun. Let’s look at these arms and how to use them. Objectives To help students understand and experience: • Muzzleloading terminology and names • Black powder and lead balls • Equipment required • Additional safety procedures involved in black powder handling and muzzle - loader shooting • Loading and firing procedures and principles • Cleaning procedures Teaching Time 2 hours (varies with number of students, instructors, and firearms) Materials You also need a short and long starter, normally As any muzzleloading shooter knows, there are combined in one tool.