I- ('A. Minor Professor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Los Angeles County – California

AZUSA CITY LOS ANGELES COUNTY CALIFORNIA, U. S. A. Azusa, California Azusa, California Azusa is a city in the San Gabriel Valley, at the foot of the San Gabriel Azusa es una ciudad en el valle de San Gabriel, al pie de las montañas de Mountains in Los Angeles County, California, United States. San Gabriel en el condado de Los Ángeles, California, Estados Unidos. The A on the San Gabriel Mountains represents the city of Azusa, and La A en las montañas de San Gabriel representa la ciudad de Azusa, y se can be seen within a 30-mile radius. The population was 46,361 at the 2010 puede ver dentro de un radio de 30 millas. La población era de 46,361 census, up from 44,712 at the 2000 census. Azusa is located along historic habitantes en el censo de 2010, frente a 44.712 en el censo de 2000. Azusa se Route 66, which passes through the city on Foothill Boulevard and Alosta encuentra a lo largo de la histórica Ruta 66, que pasa por la ciudad en Foothill Avenue. Boulevard y Alosta Avenue. Contents Contenido 1. History 1. Historia 2. Geography 2. Geografía 2.1 Climate 2.1 Clima 3. Demographics 3. Demografía 3.1 2010 3.1 2010 3.2 2000 3.2 2000 4. Economy 4. economía 5. Superfundsite 5. Superfondo 6. Government and infrastructure 6. Gobierno e infraestructura 7. Education 7. educación 7.1 Public Schools 7.1 Escuelas públicas 7.2 Private Schools. 7.2 Escuelas privadas. 8. Transportation 8. Transporte 9. -

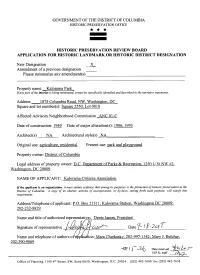

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: __Kalorama Park____________________________________________ Other names/site number: Little, John, Estate of; Kalorama Park Archaeological Site, 51NW061 Name of related multiple property listing: __N/A_________________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: __1875 Columbia Road, NW City or town: ___Washington_________ State: _DC___________ County: ____________ Not For Publication: Vicinity: ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering -

Third Edition

Third Edition v3.0 CULVER CITY, CALIFORNIA Richard Di Giacomo graduated from San Jose State University with a BA in ancient and medieval history, a BA in social science, and an MA in American history. He has been a teacher for over 25 years and has taught at-risk and limited-English students and honors and college preparatory classes. The subjects he has taught include US and world history, government, econom- ics, Bible and ethics, history of the Cold War, and contemporary world history. He has been a reviewer of and contributor to textbooks, and a frequent presenter at social studies conferences on the use of simulations, videos, and computers in education. 10200 Jefferson Boulevard, P.O. Box 802 Culver City, CA 90232-0802 United States of America (310) 839-2436 (800) 421-4246 Fax: (800) 944-5432 Fax: (310) 839-2249 www.socialstudies.com [email protected] Editorial Assistant: Manasi Patel Graphic Designer: Joseph Diaz Editorial Director: Dawn P. Dawson © 2016 Social Studies School Service All Rights Reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Only those pages intended for student use as handouts may be reproduced by the teacher who has purchased this volume. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording—without prior written permission from the publisher. Links to online versions of print media are provided in the source information. Please note that these links were valid at the time of production, but the websites may have since been discontinued. -

Daguerreian Annual 1990-2015: a Complete Index of Subjects

Daguerreian Annual 1990–2015: A Complete Index of Subjects & Daguerreotypes Illustrated Subject / Year:Page Version 75 Mark S. Johnson Editor of The Daguerreian Annual, 1997–2015 © 2018 Mark S. Johnson Mark Johnson’s contact: [email protected] This index is a work in progress, and I’m certain there are errors. Updated versions will be released so user feedback is encouraged. If you would like to suggest possible additions or corrections, send the text in the body of an email, formatted as “Subject / year:page” To Use A) Using Adobe Reader, this PDF can be quickly scrolled alphabetically by sliding the small box in the window’s vertical scroll bar. - or - B) PDF’s can also be word-searched, as shown in Figure 1. Many index citations contain keywords so trying a word search will often find other instances. Then, clicking these icons Figure 1 Type the word(s) to will take you to another in- be searched in this Adobe Reader Window stance of that word, either box. before or after. If you do not own the Daguerreian Annual this index refers you to, we may be able to help. Contact us at: [email protected] A Acuna, Patricia 2013: 281 1996: 183 Adams, Soloman; microscopic a’Beckett, Mr. Justice (judge) Adam, Hans Christian d’types 1995: 176 1995: 194 2002/2003: 287 [J. A. Whipple] Abbot, Charles G.; Sec. of Smithso- Adams & Co. Express Banking; 2015: 259 [ltr. in Boston Daily nian Institution deposit slip w/ d’type engraving Evening Transcript, 1/7/1847] 2015: 149–151 [letters re Fitz] 2014: 50–51 Adams, Zabdiel Boylston Abbott, J. -

Army Regulars on the Western Frontier, 1848-1861 / Dunvood Ball

Amy Regulars on the WestmFrontieq r 848-1 861 This page intentionally left blank Army Regulars on the Western Frontier DURWOOD BALL University of Oklahoma Press :Norman Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ball, Dunvood, 1960- Army regulars on the western frontier, 1848-1861 / Dunvood Ball. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-8061-3312-0 I. West (U.S.)-History, Military-I 9th century. 2. United States. Army-History- 19th century. 3. United States-Military policy-19th century. 4. Frontier and pioneer life-West (U.S.) 5. West (US.)-Race relations. 6. Indians of North Arnerica- Government relations-1789-1869. 7. Indians of North America-West (U.S.)- History-19th century. 8. Civil-military relations-West (U.S.)-History-19th century. 9. Violence-West (U.S.)-History-I 9th century. I. Title. F593 .B18 2001 3 5~'.00978'09034-dcz I 00-047669 CIP The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources, Inc. m Copyright O 2001 by the University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Publishing Division of the University. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the U.S.A. 12345678910 For Mom, Dad, and Kristina This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Maps IX Preface XI Acknowledgments xv INT R o D U C T I o N : Organize, Deploy, and Multiply XIX Prologue 3 PART I. DEFENSE, WAR, AND POLITICS I Ambivalent Duty: Soldiers, Indians, and Frontiersmen I 3 2 All Front, No Rear: Soldiers, Desert, and War 24 3 Chastise Them: Campaigns, Combat, and Killing 3 8 4 Internal Fissures: Soldiers, Politics, and Sectionalism 56 PART 11. -

US Army Logistics During the US-Mexican War and the Postwar Period, 1846-1860

CATALYST FOR CHANGE IN THE BORDERLANDS: U.S. ARMY LOGISTICS DURING THE U.S.-MEXICAN WAR AND THE POSTWAR PERIOD, 1846-1860 Christopher N. Menking Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 201 9 APPROVED: Richard McCaslin, Major Professor Sandra Mendiola Garcia, Committee Member Andrew Torget, Committee Member Alexander Mendoza, Committee Member Robert Wooster, Outside Reader Jennifer Jensen Wallach, Chair of the Department of History Tamara L. Brown, Executive Dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Menking, Christopher N. Catalyst for Change in the Borderlands: U.S. Army Logistics during the U.S.-Mexican War and the Postwar Period, 1846-1860. Doctor of Philosophy (History), December 2019, 323 pp., 3 figures, 3 appendices, bibliography, 52 primary sources, 140 secondary sources. This dissertation seeks to answer two primary questions stemming from the war between the United States and Mexico: 1) What methods did the United States Army Quartermaster Department employ during the war to achieve their goals of supporting armies in the field? 2) In executing these methods, what lasting impact did the presence of the Quartermaster Department leave on the Lower Río Grande borderland, specifically South Texas during the interwar period from 1848-1860? In order to obtain a complete understanding of what the Department did during the war, a discussion of the creation, evolution, and methodology of the Quartermaster Department lays the foundation for effective analysis of the department’s wartime methods and post-war influence. It is equally essential to understand the history of South Texas prior to the Mexican War under the successive control of Spain, Mexico and the United States and how that shaped the wartime situation. -

Civil War Chronicles, a Civil War Commemorative Quilt

Civil War Chronicles, a Civil War commemorative quilt Read more about history of women and the Civil War: http://library.mtsu.edu/tps/Women_and_the_Civil_War.pdf Women of the Quilt: 1. Mary Custis Lee was the wife of Robert E. Lee, the prominent career military officer who subsequently commanded the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia during the American Civil War. 2. Lizinka Campbell Ewell was the daughter of a Tennessee State senator who was also Minister to Russia under President James Monroe. In her second marriage, she married Confederate General Richard Ewell. 3. Arabella Griffith Barlow, Civil War Nurse and wife of General Francis Barlow, who spent much of the War treating wounded soldiers as part of the United States Sanitary Commission. 4. Jessie Benton Fremont, an American writer and political activist, wife of John C. Fremont, explorer of the American West and commander of the Western Region in the Civil War. 5. Mary Ann Montgomery Forrest, wife of Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest, who followed her husband across many battlefields, described as “.. moving fro place to place as the scenes of the war shifted, like a true soldier.” 6. Julia Dent Grant was the wife of the 18th President of the United States, Ulysses S. Grant, and was First Lady of the United States from 1869 to 1877. 7. Maria Garland Longstreet, wife of Confederate general James Longstreet, was the daughter of General John Garland. 8. Susan Elston Wallace was an American author and poet from Crawfordsville, Indiana. In addition to writing travel articles for several American magazines and newspapers, she published six books, five of which contain collected essays from her travels in the New Mexico Territory, Europe, and the Middle East in the 1880s. -

The Mexican General Officer Corps in the US

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Latin American Studies ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-1-2011 Valor Wrought Asunder: The exM ican General Officer Corps in the U.S.-Mexican War, 1846-1847. Javier Ernesto Sanchez Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ltam_etds Recommended Citation Sanchez, Javier Ernesto. "Valor Wrought Asunder: The exM ican General Officer Corps in the U.S.-Mexican War, 1846-1847.." (2011). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ltam_etds/3 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Latin American Studies ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Javier E. Sánchez Candidate Latin-American Studies Department This thesis is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Thesis Committee: L.M. García y Griego, Chairperson Teresa Córdova Barbara Reyes i VALOR WROUGHT ASUNDER: THE MEXICAN GENERAL OFFICER CORPS IN THE U.S.-MEXICAN WAR, 1846 -1847 by JAVIER E. SANCHEZ B.B.A., BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, UNIVERSITY OF NEW MEXICO 2009 THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December 2011 ii VALOR WROUGHT ASUNDER: THE MEXICAN GENERAL OFFICER CORPS IN THE U.S.-MEXICAN WAR, 1846-1847 By Javier E. Sánchez B.A., Business Administration, University of New Mexico, 2008 ABSTRACT This thesis presents a reappraisal of the performance of the Mexican general officer corps during the U.S.-Mexican War, 1846-1847. -

1931 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED JUNE 30 1931 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON 1931 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington. D.C. - - - Price 25 cents (paper cover) FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION CHARLES W. HUNT, Chairman. WILLIAM E HUMPHREY. CHARLES H. MARCH. EDGAR A. McCulloch. GARLAND S. FERGUSON, Jr. OTIS B. JOHNSON, Secretary. FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSIONER--1915-1931 Name State from which appointed Period of service Joseph E Davies Wisconsin Mar. 16, 1915-Mar. 18, 1918. William J. Harris Georgia Mar. 16, 1915-May 31, 1918. Edward N. Hurley Illinois Mar.16, 1915-Jan. 31, 1917. Will H. Parry Washington Mar.16, 1915-Apr. 21, 1917. George Rublee New Hampshire Mar.16, 1915-May 14, 1916. William B. Colver Minnesota Mar.16, 1917-Sept. 25, 1920. John Franklin Fort New Jersey Mar.16, 1917-Nov. 30, 1919. Victor Murdock Kansas Sept. 4, 1917-Jan. 31, 1924. Huston Thompson Colorado Jan.17, 1919-Sept. 25, 1926. Nelson B. Gaskill New Jersey Feb. 1, 1920-Feb. 24, 1925. John Garland Pollard Virginia Mar. 6, 1925-Sept. 25,1921. John F. Nugent Idaho Jan.15, 1921-Sept. 25, 1927 Vernon W. Van Fleet Indiana June 26, 1922-July 31, 1926. C. W. Hunt Iowa June 16, 1924. William E Humphrey Washington Feb.25, 1925. Abram F. Myers Iowa Aug. 2, 1926-Jan. 15, 1929. Edgar A. McCulloch Arkansas Feb.11, 1927. G. S. Ferguson, Jr North Carolina Nov.14, 1927. Charles H. March Minnesota Feb. 1, 1929. GENERAL OFFICES OF THE COMMISSION 1800 Virginia Avenue, NW., Washington BRANCH OFFICES 608 South Dearborn Street 45 Broadway Chicago New York 544 Market Street 431 Lyon Building San Francisco Seattle II CONTENTS PART I. -

Trade and Plunder Networks in the Second Seminole War in Florida, 1835-1842

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Trade and Plunder Networks in the Second Seminole War in Florida, 1835-1842 Toni Carrier University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Carrier, Toni, "Trade and Plunder Networks in the Second Seminole War in Florida, 1835-1842" (2005). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/2811 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Trade and Plunder Networks in the Second Seminole War in Florida, 1835-1842 by Toni Carrier A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Brent R. Weisman, Ph.D. Robert H. Tykot, Ph.D. Trevor R. Purcell, Ph.D. Date of Approval: April 14, 2005 Keywords: Social Capital, Political Economy, Black Seminoles, Illicit Trade, Slaves, Ranchos, Wreckers, Slave Resistance, Free Blacks, Indian Wars, Indian Negroes, Maroons © Copyright 2005, Toni Carrier Dedication To my baby sister Heather, 1987-2001. You were my heart, which now has wings. Acknowledgments I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to the many people who mentored, guided, supported and otherwise put up with me throughout the preparation of this manuscript. To Dr. -

Proceedings First Annual Palo Alto Conference

PROCEEDINGS OF THE FIRST ANNUAL PALO ALTO CONFERENCE An International Conference on the Mexican-American War and its Causes and Consequences with Participants from Mexico and the United States. Brownsville, Texas, May 6-9, 1993 Palo Alto Battlefield National Historic Site Southwest Region National Park Service I Cover Illustration: "Plan of the Country to the North East of the City of Matamoros, 1846" in Albert I C. Ramsey, trans., The Other Side: Or, Notes for the History of the War Between Mexico and the I United States (New York: John Wiley, 1850). 1i L9 37 PROCEEDINGS OF THE FIRST ANNUAL PALO ALTO CONFERENCE Edited by Aaron P. Mahr Yafiez National Park Service Palo Alto Battlefield National Historic Site P.O. Box 1832 Brownsville, Texas 78522 United States Department of the Interior 1994 In order to meet the challenges of the future, human understanding, cooperation, and respect must transcend aggression. We cannot learn from the future, we can only learn from the past and the present. I feel the proceedings of this conference illustrate that a step has been taken in the right direction. John E. Cook Regional Director Southwest Region National Park Service TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction. A.N. Zavaleta vii General Mariano Arista at the Battle of Palo Alto, Texas, 1846: Military Realist or Failure? Joseph P. Sanchez 1 A Fanatical Patriot With Good Intentions: Reflections on the Activities of Valentin GOmez Farfas During the Mexican-American War. Pedro Santoni 19 El contexto mexicano: angulo desconocido de la guerra. Josefina Zoraida Vazquez 29 Could the Mexican-American War Have Been Avoided? Miguel Soto 35 Confederate Imperial Designs on Northwestern Mexico. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 13, 1986

Journal of Mormon History Volume 13 Issue 1 Article 1 1986 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 13, 1986 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1986) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 13, 1986," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 13 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol13/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 13, 1986 Table of Contents • --Mormon Women, Other Women: Paradoxes and Challenges Anne Firor Scott, 3 • --Strangers in a Strange Land: Heber J. Grant and the Opening of the Japanese Mission Ronald W. Walker, 21 • --Lamanism, Lymanism, and Cornfields Richard E. Bennett, 45 • --Mormon Missionary Wives in Nineteenth Century Polynesia Carol Cornwall Madsen, 61 • --The Federal Bench and Priesthood Authority: The Rise and Fall of John Fitch Kinney's Early Relationship with the Mormons Michael W. Homer, 89 • --The 1903 Dedication of Russia for Missionary Work Kahlile Mehr, 111 • --Between Two Cultures: The Mormon Settlement of Star Valley, Wyoming Dean L.May, 125 Keywords 1986-1987 This full issue is available in Journal of Mormon History: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol13/iss1/ 1 Journal of Mormon History Editorial Staff LEONARD J. ARRINGTON, Editor LOWELL M. DURHAM, Jr., Assistant Editor ELEANOR KNOWLES, Assistant Editor FRANK McENTIRE, Assistant Editor MARTHA ELIZABETH BRADLEY, Assistant Editor JILL MULVAY DERR, Assistant Editor Board of Editors MARIO DE PILLIS (1988), University of Massachusetts PAUL M.