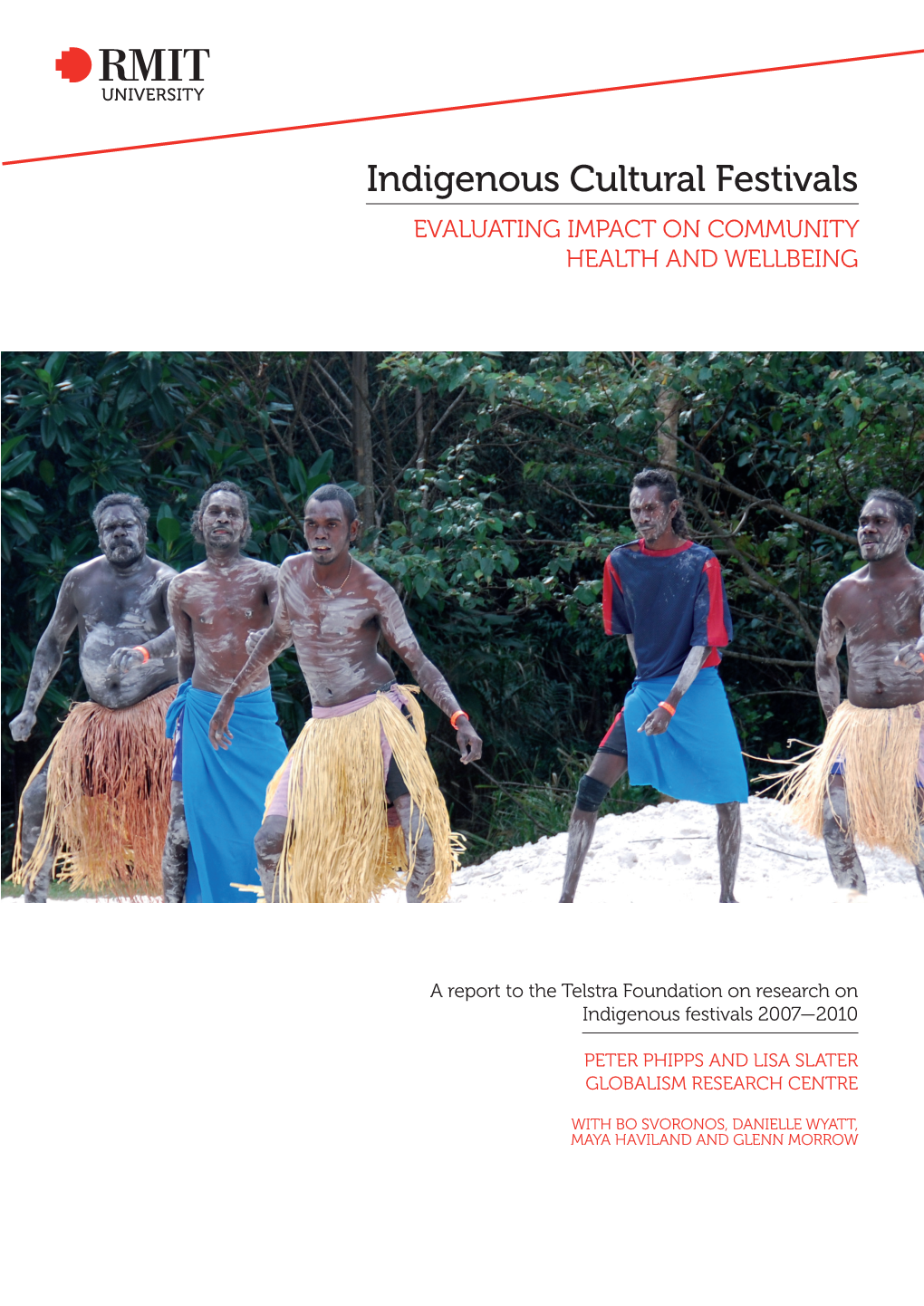

Indigenous Cultural Festivals EVALUATING IMPACT on COMMUNITY HEALTH and WELLBEING

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Into the Mainstream Guide to the Moving Image Recordings from the Production of Into the Mainstream by Ned Lander, 1988

Descriptive Level Finding aid LANDER_N001 Collection title Into the Mainstream Guide to the moving image recordings from the production of Into the Mainstream by Ned Lander, 1988 Prepared 2015 by LW and IE, from audition sheets by JW Last updated November 19, 2015 ACCESS Availability of copies Digital viewing copies are available. Further information is available on the 'Ordering Collection Items' web page. Alternatively, contact the Access Unit by email to arrange an appointment to view the recordings or to order copies. Restrictions on viewing The collection is open for viewing on the AIATSIS premises. AIATSIS holds viewing copies and production materials. Contact AFI Distribution for copies and usage. Contact Ned Lander and Yothu Yindi for usage of production materials. Ned Lander has donated production materials from this film to AIATSIS as a Cultural Gift under the Taxation Incentives for the Arts Scheme. Restrictions on use The collection may only be copied or published with permission from AIATSIS. SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Date: 1988 Extent: 102 videocassettes (Betacam SP) (approximately 35 hrs.) : sd., col. (Moving Image 10 U-Matic tapes (Kodak EB950) (approximately 10 hrs.) : sd, col. components) 6 Betamax tapes (approximately 6 hrs.) : sd, col. 9 VHS tapes (approximately 9 hrs.) : sd, col. Production history Made as a one hour television documentary, 'Into the Mainstream' follows the Aboriginal band Yothu Yindi on its journey across America in 1988 with rock groups Midnight Oil and Graffiti Man (featuring John Trudell). Yothu Yindi is famed for drawing on the song-cycles of its Arnhem Land roots to create a mix of traditional Aboriginal music and rock and roll. -

Djambawa Marawili

DJAMBAWA MARAWILI Date de naissance : 1953 Communauté artistique : Yirrkala Langue : Madarrpa Support : pigments naturels sur écorce, sculpture sur bois, gravure sur linoleum Nom de peau : Yirritja Thèmes : Yinapungapu, Yathikpa, Burrut'tji, Baru - crocodile, heron, fish, eagle, dugong Djambawa Marawili (born 1953) is an artist who has experienced mainstream success (as the winner of the 1996 Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art award Best Bark Painting Prize and as an artist represented in most major Australian institutional collections and several important overseas public and private collections) but for whom the production of art is a small part of a much bigger picture. Djambawa as a senior artist as well as sculpture and bark painting has produced linocut images and produced the first screenprint image for the Buku-Larr\gay Mulka Printspace. His principal roles are as a leader of the Madarrpa clan, a caretaker for the spiritual wellbeing of his own and other related clan’s and an activist and administrator in the interface between non-Aboriginal people and the Yol\u (Aboriginal) people of North East Arnhem Land. He is first and foremost a leader, and his art is one of the tools he uses to lead. As a participant in the production of the Barunga Statement (1988),which led to Bob Hawke’s promise of a treaty, the Royal Commission into Black Deaths in Custody and the formation of ATSIC , Djambawa drew on the sacred foundation of his people to represent the power of Yolngu and educate ‘outsiders’ in the justice of his people’s struggle for recognition. -

Annual Report 2011–12 Annual Report 2011–12 the National Gallery of Australia Is a Commonwealth (Cover) Authority Established Under the National Gallery Act 1975

ANNUAL REPORT 2011–12 ANNUAL REPORT 2011–12 The National Gallery of Australia is a Commonwealth (cover) authority established under the National Gallery Act 1975. Henri Matisse Oceania, the sea (Océanie, la mer) 1946 The vision of the National Gallery of Australia is the screenprint on linen cultural enrichment of all Australians through access 172 x 385.4 cm to their national art gallery, the quality of the national National Gallery of Australia, Canberra collection, the exceptional displays, exhibitions and gift of Tim Fairfax AM, 2012 programs, and the professionalism of our staff. The Gallery’s governing body, the Council of the National Gallery of Australia, has expertise in arts administration, corporate governance, administration and financial and business management. In 2011–12, the National Gallery of Australia received an appropriation from the Australian Government totalling $48.828 million (including an equity injection of $16.219 million for development of the national collection), raised $13.811 million, and employed 250 full-time equivalent staff. © National Gallery of Australia 2012 ISSN 1323 5192 All rights reserved. No part of this publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Produced by the Publishing Department of the National Gallery of Australia Edited by Eric Meredith Designed by Susannah Luddy Printed by New Millennium National Gallery of Australia GPO Box 1150 Canberra ACT 2601 nga.gov.au/AboutUs/Reports 30 September 2012 The Hon Simon Crean MP Minister for the Arts Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister On behalf of the Council of the National Gallery of Australia, I have pleasure in submitting to you, for presentation to each House of Parliament, the National Gallery of Australia’s Annual Report covering the period 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2012. -

Reconciliation-Week-Booklist

Reconciliation Week Resources on Reconciliation: Books to read, videos and music for Monash staff and students, mainly available through Search TITLE Behrendt, Larissa. Home. St Lucia, Qld: University of Queensland Press, 2004. – Online and PRINT Behrendt, Larissa. Resolving Indigenous Disputes: Land Conflict and Beyond. Leichhardt, NSW: The Federation Press, 2008. - PRINT Birch, Tony, Broken Teeth - PRINT Elder, Bruce. Blood on the Wattle: Massacres and Maltreatment of Aboriginal Australians since 1788. Frenchs Forest, NSW: New Holland, 3rd ed. 2003 - PRINT Frankland, Richard. Digger J Jones. Linfield NSW: Scholastic Press, 2007. - PRINT Frankland, Richard. Walking into Bigness. Strawberry Hills, NSW: Currency Press, 2017. - PRINT Gillespie, Neil. Reflections: 40 Years on from the 1967 Referendum. Adelaide: Aboriginal Legal Rights Movement, 2007 – PRINT Howarth, Kate. Ten Hail Marys: A Memoir. St Lucia, Qld: University of Queensland Press, 2010 - PRINT Langton, Marcia, Welcome to country : a travel guide to Indigenous Australia, (2018) – PRINT Moreton-Robinson, Aileen. Talkin’ up to the White Woman: Aboriginal Women and Feminism. St Lucia, Qld: University of Queensland Press, 2000 – PRINT Moreton-Robinson, Aileen. Sovereign Subjects: Indigenous Sovereignty Matters ,Crows Nest, N.S.W.: Allen & Unwin, 2007- PRINT Moreton-Robinson, Aileen. The White Possessive: Property, Power and Indigenous Sovereignty. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015 - ONLINE Ogden, John, Saltwater people of the Fatal Shore (2012) - PRINT Pascoe, Bruce. Dark Emu: Black Seeds, Agriculture or Accident? Broome, WA: Magabala Books, 2014 PRINT and ONLINE Pascoe, Bruce. Convincing Ground: Learning to Fall in Love with your Country. Canberra ACT: Aboriginal Studies Press, 2007 PRINT & ONLINE Russell, Lynette. Savage Imaginings: Historical and Contemporary Constructions of Australian Aboriginalities. -

Unbranded Unbranded 06052019 — 22062019

unbranded unbranded 06052019 — 22062019 121 View St BENDIGO Victoria 3550 Damien Shen Dean Cross Gunybi Ganambarr Illiam Nargoodah James Tylor John Prince Siddon Ngarralja Tommy May Noŋgirrŋa Marawili Nyurpaya Kaika Burton Patrina Munuŋgurr Sharyn Egan Sonia Kurarra Wukun Wanambi Cover image: Sonia Kurarra, Martuwarra, 2015, syntheti c polymer paint on canvas, 152 x 137cm. Courtesy of the arti st and Mangkaja Arts. Image left : Gunybi Ganambarr at Gangan. Photo by Dave Wickens. Courtesy of the arti st and Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre. unbranded presents work by Indigenous contemporary unbranded as a curatorial enterprise questions these artists whose practices undermine and subvert the notion reductive and divisive modes of representation and of a singular Indigenous ‘brand’ or ‘aesthetic’. Their work interpretation, while simultaneously affirming the unpicks preconceptions of what Indigenous creative diversity, multiplicity and complexity of contemporary practice is or, should be, rejecting binary assumptions Indigenous experience, both live and inherited. around ‘traditional/non-traditional’, or ‘urban/remote’ practices and other applied, and often arbitrary Emerging from ongoing discussions around the premise categorisations. Their work instead reflects multiplicity, established by Glenn Iseger-Pilkington in his essay complexity and sometimes-conflicting experiences of Branded: the Indigenous Aestheticoriginally published by culture and identity in contemporary Australia. the Centre for Contemporary Photography (CCP) in 2009, unbranded challenges the relevance of an The act of ‘branding’, clustering often disparate products ‘Indigenous brand’ or ‘aesthetic’, and refutes the notion together for marketing purposes, strips the voice of the that such a brand can somehow represent the experience individual artist or maker and separates creative output of Indigenous artists and Indigenous people across from the contemporary context in which it is created. -

Humanities Research Vol XIX. No. 2. 2013

Nations of Song Aaron Corn Eye-witness testimony is the lowest form of evidence. — Neil deGrasse Tyson, astrophysicist1 Poets are almost always wrong about facts. That’s because they are not really interested in facts: only in truth. — William C. Faulkner, writer2 Whether we evoke them willingly or whether they manifest in our minds unannounced, songs travel with us constantly, and frequently hold for us fluid, negotiated meanings that would mystify their composers. This article explores the varying degrees to which song, and music more generally, is accepted as a medium capable of bearing fact. If, as Merleau-Ponty postulated,3 external cultural expressions are but artefacts of our inner perceptions, which media do we reify and canonise as evidential records of our history? Which media do we entrust with that elusive commodity, truth? Could it possibly be carried by a song? To illustrate this argument, I will draw on my 15 years of experience in working artistically and intellectually with the Yolŋu people of north-east Arnhem Land in Australia’s remote north, who are among the many Indigenous peoples whose sovereignty in Australia predates the British occupation of 1788.4 As owners of song and dance traditions that formally document their law and are performed to conduct legal processes, the Yolŋu case has been a focus of prolonged political contestation over such nations of song, and also raises salient questions about perceived relations between music and knowledge within the academy, where meaning and evidence are conventionally rendered in text. This article was originally presented as a keynote address to the joint meeting of the Musicological Society of Australia and the New Zealand Musicological Society at the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand, in December 2010. -

Land, Song, Constitution: Exploring Expressions of Ancestral Agency, Intercultural Diplomacy and Family Legacy in the Music of Yothu Yindi with Mandawuy Yunupiŋu1

Popular Music (2010) Volume 29/1. Copyright © Cambridge University Press 2010, pp. 81–102 doi:10.1017/S0261143009990390 Land, song, constitution: exploring expressions of ancestral agency, intercultural diplomacy and family legacy in the music of Yothu Yindi with Mandawuy Yunupiŋu1 AARON CORN Pacific & Regional Archive for Digital Sources in Endangered Cultures, F12 – Transient, The University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Yothu Yindi stands as one of Australia’s most celebrated popular bands, and in the early 1990s became renowned worldwide for its innovative blend of rock and indigenous performance traditions. The band’s lead singer and composer, Mandawuy Yunupiŋu, was one of the first university-trained Yolŋu educators from remote Arnhem Land, and an influential exponent of bicultural education within local indigenous schools. This article draws on my comprehensive interview with Yunupiŋuforan opening keynote address to the Music and Social Justice Conference in Sydney on 28 September 2005. It offers new insights into the traditional values and local history of intercultural relations on the Gove Peninsula that shaped his outlook as a Yolŋu educator, and simultaneously informed his work through Yothu Yindi as an ambassador for indigenous cultural survival in Australia. It also demonstrates how Mandawuy’s personal history and his call for a constitutional treaty with indigen- ous Australians are further grounded in the inter-generational struggle for justice over the mining of their hereditary lands. The article’s ultimate goal is to identify traditional Yolŋu meanings in Yothu Yindi’s repertoire, and in doing so, generate new understanding of Yunupiŋu’s agency as a prominent intermediary of contemporary Yolŋu culture and intercultural politics. -

Download PDF CV

BUKU-~ARR|GAY MULKA Yirrkala NT 0880 Phone 08 8987 1701 Fax 08 8987 2701 www.yirrkala.com [email protected] Djambawa Marawili Other Names Miniyawany Born 13/04/53 Died na Moiety Yirritja moiety Homeland Baniyala Clan Yithuwa Ma[arrpa - Nyu\u[upuy Ma[arrpa Selected Details of Artist’s Working Life Medium and Theme Earth Pigments on Bark Incised and painted wood scupture Printmaking Ceremonial objects - hollow log coffins Biography Djambawa Marawili (born 1953) is an artist who has experienced mainstream success (as the winner of the 1996 Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art award Best Bark Painting Prize and as an artist represented in most major Australian institutional collections and several important overseas public and private collections) but for whom the production of art is a small part of a much bigger picture. Djambawa as a senior artist as well as sculpture and bark painting has produced linocut images and produced the first screenprint image for the Buku-Larr\gay Mulka Printspace. His principal roles are as a leader of the Madarrpa clan, a caretaker for the spiritual well-being of his own and other related clan’s and an activist and administrator in the interface between non-Aboriginal people and the Yol\u (Aboriginal) people of North East Arnhem Land. He is first and foremost a leader, and his art is one of the tools he uses to lead. As a participant in the production of the Barunga Statement (1988),which led to Bob Hawke’s promise of a treaty, the Royal Commission into Black Deaths in Custody and the formation of ATSIC , Djambawa drew on the sacred foundation of his people to represent the power of Yolngu and educate ‘outsiders’ in the justice of his people’s struggle for recognition. -

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Perspectives

NOVELS Baillie, Allan The First Voyage F BAI:A An adventure story set in our very distant past, 30,000 years ago, when the first tribes from Timor braved the ocean on primitive rafts to travel into the unknown, and reached the land mass of what is now Australia. Baillie, Allan Songman F BAI:A This story is set in northern Australia in 1720, before the time of Captain Cook. Yukuwa sets out across the sea to the islands of Indonesia. It is an adventure contrasting lifestyles and cultures, based on an episode of our history rarely explored in fiction. Birch, Tony, The White Girl F BIR:T Odette Brown has lived her whole life on the fringes of a small country town. After her daughter disappeared and left her with her granddaughter Sissy to raise on her own, Odette has managed to stay under the radar of the welfare authorities who are removing fair-skinned Aboriginal children from their families. When a new policeman arrives in town, determined to enforce the law, Odette must risk everything to save Sissy and protect everything she loves. Boyd, Jillian Bakir and Bi F BOY:J Bakir and Bi is based on a Torres Strait Islander creation story with illustrations by 18-year-old Tori-Jay Mordey. Bakir and Mar live on a remote island called Egur with their two young children. While fishing on the beach Bakir comes across a very special pelican named Bi. A famine occurs, and life on the island is no longer harmonious. Bunney, Ron The Hidden F BUN:R Thrown out of home by his penny-pinching stepmother, Matt flees Freemantle aboard a boat, only to be bullied and brutalised by the boson. -

The Wider Indigenous Community Benefits of Yirralka Rangers in Blue Mud Bay, Northeast Arnhem Land | Final Report

Rangers in place: the wider Indigenous community benefits of Yirralka Rangers in Blue Mud Bay, northeast Arnhem Land | Final report By Marcus Barber Report Title Author’s name Acknowledgements My sincere thanks go to the rangers and residents of Baniyala and GanGan in Northeast Arnhem Land, in particular Madarrpa clan elder and Baniyala community leader Djambawa Marawili. Thanks to staff at the Yirralka Rangers, The Mulka Project, and the Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Arts Centre. This research was funded by the National Environmental Research Program, Northern Australia Hub supported by the Water for a Health Country and the Land & Water Flagships of the CSIRO. Thanks to Sue Jackson for her project leadership and considerable contribution to the literature review in Section 2 which is based on a forthcoming paper. Thanks also to fellow researchers on NERP 2.1 Indigenous livelihoods – Jon Altman, Sean Kerins, and Nic Gambold. Cathy Robinson, Sue Jackson, and David Preece provided important comments on the draft of this report. Film production would not have been possible without the invaluable contributions of Ishmael Marika and Joseph Brady from the Mulka Project, editorial expertise from Vidhi Shah, and logistical support by David Preece and other staff from Yirralka Rangers. Front cover: Male rangers on sea patrol Back cover: Female Yirralka Rangers making soap at Baniyala ranger station Important disclaimer CSIRO advises that the information contained in this publication comprises general statements based on scientific research. The reader is advised and needs to be aware that such information may be incomplete or unable to be used in any specific situation. -

Ultima Thule 629: Sydney 05 November - Adelaide 12 November 2006

Ultima Thule 629: Sydney 05 November - Adelaide 12 November 2006 No Track Title Composer Artist Album Label Catalogue Dur 1 Birdcall samples n/a Terra Australia Music In Harmony With Nature Terra Australia 1220778 3.15 Ancient Legends (Rawal 2 Gene Pierson, Nigel Pegrum Ash Dargan Spirit Dreams Indigenous Australia IA2024D 3.07 Woggheegui) Adam Plack + Jason Oliver 3 Willi Willi (Spirits in the Sky) Adam Plack Winds of Warning Australian Music International AMI 2002-2 4.32 Baker Music & Dreamtime Stories of 4 Introduction Bob Maza + T Laiwongka Bob Maza + T Laiwongka Larrakin LRF479 1.17 the Australian Aborigines 5 Gapu Traditional (arr GYunupingu) Yothu Yindi Tribal Voice Mushroom RMD53358 2.43 6 Winds of Warning Adam Plack Adam Plack Winds of Warning Australian Music International AMI 2002-2 5.11 7 Bat Attack Scott Wilson Didjibyte The Web (2006 Remaster) n/a DJBE893 1.51 8 Gany'tjurr Traditional (arr G Yunupingu) Yothu Yindi Freedom Mushroom rmd53380 2.13 Sacred Memories Of The 9 Deep Down In The Jungle B de Rose + J Deere CyberTribe New Earth Rec NE9712-2 4.07 Future 10 First Contact as above as above as above as above as above 1.47 11 Ninu Charlie McMahon Charlie McMahon Tjilatjila Oceanic Music OM9011D 4.50 C McMahon, E Duquemin, D 12 Top End Gondwana Xenophon Shock Shock0027 4.24 Liawonga + T Kelly 13 Cocoa Soul Didgeri Stu, Matt, Chris Oka Elements Independent Project Records 6775332 5.59 14 Deep In Didge M James, R Bradshaw + N Lane Tribal Trance Didgin' in the Dirt n/a B00003ZAMK 9.44 15 Remember Kailash + Alain Eskinasi Kailash -

PROMOTING DIVERSITY of CULTURAL EXPRESSION in ARTS in AUSTRALIA a Case Study Report

PROMOTING DIVERSITY OF CULTURAL EXPRESSION IN ARTS IN AUSTRALIA A case study report Dr Phillip Mar Institute for Culture and Society, Western Sydney University Distinguished Professor Ien Ang Institute for Culture and Society, Institute for Culture Western Sydney University and Society DIVERSITY OF CULTURAL EXPRESSIONS Published under Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-NonDerivative Works 2.5 License Any distribution must include the following attribution: P.Mar & I.Ang (2015) Promoting Diversity of Cultural Expressions in Arts in Australia, Sydney, Australia Council for the Arts. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Dr Phillip Mar Phillip Mar is an anthropologist by training, with research interests in migration, political emotions, contemporary art and cultural policy. Since 2008, Phillip Mar has been a researcher at the Centre for Cultural Research / Institute for Culture and Society, Western Sydney University. Distinguished Professor Ien Ang Ien Ang is a Distinguished Professor of Cultural Studies at the Institute for Culture and Society (ICS) at Western Sydney University. She is one of the leaders in cultural studies worldwide, with interdisciplinary work spanning many areas of the humanities and social sciences, focusing broadly on the processes and impacts of cultural flow and exchange in the globalised world. Her books, including Watching Dallas, Desperately Seeking the Audience and On Not Speaking Chinese, are recognised as classics in the field and her work has been translated into many languages, including Chinese, Japanese, Italian, Turkish, German, Korean and Spanish. Her most recent book, co-edited with E. Lally and K. Anderson, is The Art of Engagement: Culture, Collaboration, Innovation (2011). She is also the co-author (with Y.