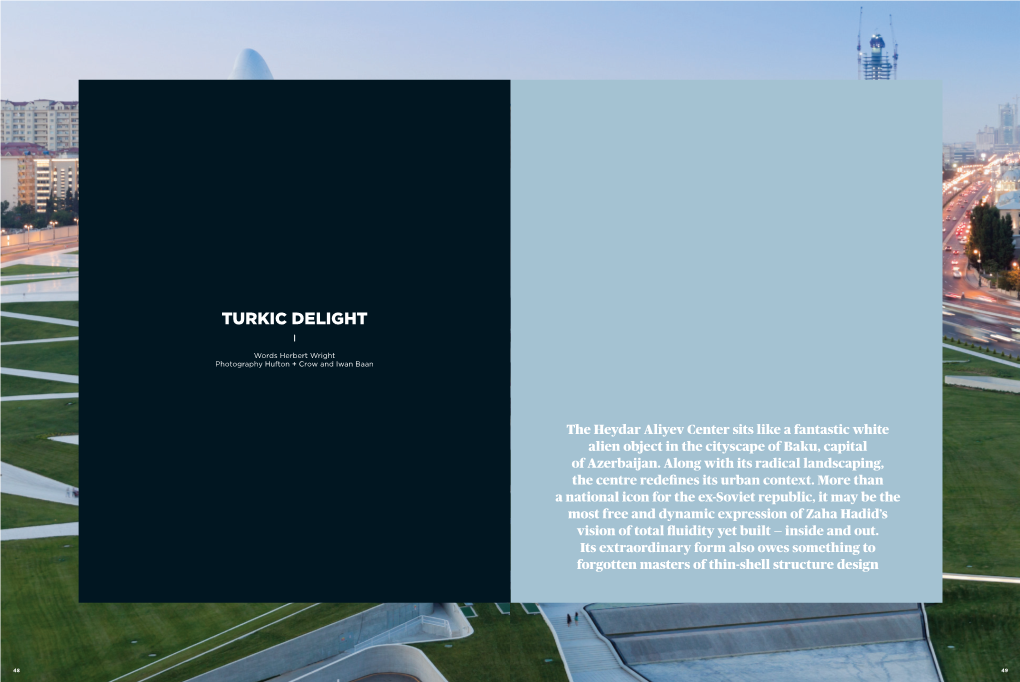

Turkic Delight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IAUP Baku 2018 Semi-Annual Meeting

IAUP Baku 2018 Semi-Annual Meeting “Globalization and New Dimensions in Higher Education” 18-20th April, 2018 Venue: Fairmont Baku, Flame Towers Website: https://iaupasoiu.meetinghand.com/en/#home CONFERENCE PROGRAMME WEDNESDAY 18th April 2018 Fairmont Baku, Flame Towers 18:30 Registration 1A, Mehdi Hüseyn Street Fairmont Baku, Flame Towers, 19:00-21:00 Opening Cocktail Party Uzeyir Hajibeyov Ballroom, 19:05 Welcome speech by IAUP President Mr. Kakha Shengelia 19:10 Welcome speech by Ministry of Education representative 19:30 Opening Speech by Rector of ASOIU Mustafa Babanli THURSDAY 19th April 2018 Visit to Alley of Honor, Martyrs' Lane Meeting Point: Foyer in Fairmont 09:00 - 09:45 Hotel 10:00 - 10:15 Mr. Kakha Shengelia Nizami Ganjavi A Grand Ballroom, IAUP President Fairmont Baku 10:15 - 10:30 Mr. Ceyhun Bayramov Deputy Minister of Education of the Republic of Azerbaijan 10:30-10:45 Mr. Mikheil Chkhenkeli Minister of Education and Science of Georgia 10:45 - 11:00 Prof. Mustafa Babanli Rector of Azerbaijan State Oil and Industry University 11:00 - 11:30 Coffee Break Keynote 1: Modern approach to knowledge transfer: interdisciplinary 11:30 - 12:00 studies and creative thinking Speaker: Prof. Philippe Turek University of Strasbourg 12:00 - 13:00 Panel discussion 1 13:00 - 14:00 Lunch 14:00 - 15:30 Networking meeting of rectors and presidents 14:00– 16:00 Floor Presentation of Azerbaijani Universities (parallel to the networking meeting) 18:30 - 19:00 Transfer from Farimont Hotel to Buta Palace Small Hall, Buta Palace 19:00 - 22:00 Gala -

Best of Baku

Best of Baku Starting From :Rs.:22800 Per Person 5 Days / 4 Nights BAKU .......... Package Description Best of Baku Azerbaijan’s capital is the architectural love child of Paris and Dubai…albeit with plenty of Soviet genes floating half-hidden in the background. Few cities in the world are changing as quickly and nowhere else in the Caucasus do East and West blend as seamlessly or as chaotically. At its heart, the UNESCO-listed lies within an exotically crenellated arc of fortress wall. Around this are gracefully illuminated stone mansions and pedestrianized tree-lined streets filled with exclusive boutiques. The second oil boom, which started around 2006, has turned the city into a crucible of architectural experimentation and some of the finest new buildings are jaw-dropping masterpieces. Meanwhile romantic couples canoodle their way around wooded parks and hold hands on the Caspian-front boulevard , where greens and opal blues make a mockery of Baku’s desert-ringed location. .......... Itinerary Day.1 WELCOME TO BAKU Arrival at Airport Transfer from Airport to Restaurant LUNCH AT INDIAN RESTAURANT Assembly at hotel lobby in sunset time. Proceed to evening city view tour with car Visit toHighland Park-Alley of Martyrs, The National Assembly- also transliterated as Milli Majlis, Flame towers-the tallest skyscraper in Baku. Walking through Baku Boulevard which stretches along a south-facing bay on the Caspian Sea. It traditionally starts at Freedom Square continuing west to the Old City and beyond. Since 2012, the Yeni Bulvar (New Boulevard) has virtually doubled the length to 3.75 km. DINNER AT RESTAURANT Back to Hotel Meals:Lunch + Dinner Copyright © www.lotustravelsonline.com Day.2 BAKU CITY TOUR Breakfast in Hotel Our tour program starts withOld City or Inner City is the historical core of Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan. -

Azerbaijan 2017 Crime & Safety Report

Azerbaijan 2017 Crime & Safety Report Overall Crime and Safety Situation U.S. Embassy Baku does not assume responsibility for the professional ability or integrity of the persons or firms appearing in this report. The ACS Unit cannot recommend a particular individual or location and assumes no responsibility for the quality of service provided. THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE HAS ASSESSED BAKU AS BEING A MEDIUM-THREAT LOCATION FOR CRIME DIRECTED AT OR AFFECTING OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT INTERESTS. Please review OSAC’s Azerbaijan-specific webpage for proprietary analytic reports, Consular Messages, and contact information. Crime Threats Criminal acts committed against foreigners are infrequent in Baku. The majority of reported crimes involve Azerbaijani citizens, with burglary and assault being the most common. Late- night targeted attacks against lone men are the most common crimes perpetrated against foreigners. Petty thefts (pickpocketing), while not common, are sometimes perpetrated against foreigners in Baku. Expatriates are at greater risk of being victims of petty crime in areas that attract large crowds or are very isolated. Some U.S. citizens, most commonly males, have reported being victims of certain scams in bars frequented by Westerners. Commonly, a male patron is approached by a young woman who asks him to buy her a drink. After buying the woman a drink and conversing, the male is presented with a bill for 375 AZN (approximately US$200). When he protests, he is approached by several men, detained, and forced to pay the full amount under threat of physical violence. Some women have reported incidents of unwanted male attention, including groping and other inappropriate behavior while walking on the streets alone and when taking taxis. -

Sustainable Urban Mobility and Public Transport in Unece Capitals

UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE SUSTAINABLE URBAN MOBILITY AND PUBLIC TRANSPORT IN UNECE CAPITALS UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE SUSTAINABLE URBAN MOBILITY AND PUBLIC TRANSPORT IN UNECE CAPITALS This publication is part of the Transport Trends and Economics Series (WP.5) New York and Geneva, 2015 ©2015 United Nations All rights reserved worldwide Requests to reproduce excerpts or to photocopy should be addressed to the Copyright Clearance Center at copyright.com. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to: United Nations Publications, 300 East 42nd St, New York, NY 10017, United States of America. Email: [email protected]; website: un.org/publications United Nations’ publication issued by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Maps and country reports are only for information purposes. Acknowledgements The study was prepared by Mr. Konstantinos Alexopoulos and Mr. Lukasz Wyrowski. The authors worked under the guidance of and benefited from significant contributions by Dr. Eva Molnar, Director of UNECE Sustainable Transport Division and Mr. Miodrag Pesut, Chief of Transport Facilitation and Economics Section. ECE/TRANS/245 Transport in UNECE The UNECE Sustainable Transport Division is the secretariat of the Inland Transport Committee (ITC) and the ECOSOC Committee of Experts on the Transport of Dangerous Goods and on the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals. -

Azerbaijan | Freedom House

Azerbaijan | Freedom House http://freedomhouse.org/report/nations-transit/2014/azerbaijan About Us DONATE Blog Mobile App Contact Us Mexico Website (in Spanish) REGIONS ISSUES Reports Programs Initiatives News Experts Events Subscribe Donate NATIONS IN TRANSIT - View another year - ShareShareShareShareShareMore 7 Azerbaijan Azerbaijan Nations in Transit 2014 DRAFT REPORT 2014 SCORES PDF version Capital: Baku 6.68 Population: 9.3 million REGIME CLASSIFICATION GNI/capita, PPP: US$9,410 Consolidated Source: The data above are drawn from The World Bank, Authoritarian World Development Indicators 2014. Regime 6.75 7.00 6.50 6.75 6.50 6.50 6.75 NOTE: The ratings reflect the consensus of Freedom House, its academic advisers, and the author(s) of this report. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author(s). The ratings are based on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 representing the highest level of democratic progress and 7 the lowest. The Democracy Score is an average of ratings for the categories tracked in a given year. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: 1 of 23 6/25/2014 11:26 AM Azerbaijan | Freedom House http://freedomhouse.org/report/nations-transit/2014/azerbaijan Azerbaijan is ruled by an authoritarian regime characterized by intolerance for dissent and disregard for civil liberties and political rights. When President Heydar Aliyev came to power in 1993, he secured a ceasefire in Azerbaijan’s war with Armenia and established relative domestic stability, but he also instituted a Soviet-style, vertical power system, based on patronage and the suppression of political dissent. Ilham Aliyev succeeded his father in 2003, continuing and intensifying the most repressive aspects of his father’s rule. -

Azerbaijan 2019 Crime & Safety Report

Azerbaijan 2019 Crime & Safety Report This is an annual report produced in conjunction with the Regional Security Office at the U.S. Embassy in Baku, Azerbaijan. The current U.S. Department of State Travel Advisory at the date of this report’s publication assesses Azerbaijan at Level 2, indicating travelers should exercise increased cautions due to the risk of terrorism. Do not travel to the Nagorno-Karabakh region due to armed conflict. Overall Crime and Safety Situation The U.S. Embassy in Baku does not assume responsibility for the professional ability or integrity of the persons or firms appearing in this report. The American Citizen Services unit (ACS) of the Embassy’s Consular Section cannot recommend a particular individual or location and assumes no responsibility for the quality of service provided. Review OSAC’s Azerbaijan-specific page for original OSAC reporting, consular messages, and contact information, some of which may be available only to private-sector representatives with an OSAC password. Crime Threats There is moderate risk from crime in Baku. Criminal acts committed against foreigners are infrequent in Baku. Most reported crimes involve Azerbaijani citizens, with burglary and assault the most common. Late-night attacks targeted against lone men are the most common crimes against foreigners. While not common, expatriates are at greater risk of being victims of petty crime (e.g. pickpocketing) in areas that attract large crowds or are very isolated. Some women have reported incidents of unwanted male attention, including touching and other inappropriate behavior, while walking on the streets or taking taxis alone. While the number of reported sexual assaults is statistically very low, this is likely an underreported issue due to cultural stigma. -

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I a L L I B R a R Y

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y CHRONOLOGY Chronology of events that led Azerbaijan to independence and remarkable days after gaining the independence An extraordinary session of the Council of People's Deputies February 20,1988 of the Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Republic (NKAR) was held in Hankendi. The session appealed to the Presidium of Supreme Soviet of Azerbaijan and Armenia with the request that they treat with understanding the decision to sever the NKAR from Azerbaijan SSR and transfer it to Armenian SSR. It was also applied to the Supreme Soviet of the USSR for the positive solution of this issue. February 22,1988 Two young Azerbaijanis were killed by Armenians in Askeran February 28,1988 Bloody outrages were perpetrated by Armenian instigators in Sumgait March 24, 1988 By the decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Council of Azerbaijan SSR an official prohibition was imposed on activity of separatist organization "Krung" to be accused of breeding strife among the peoples. Abdurrahman Vezirov was elected the first secretary of the Central May 21,1988 Committee of the Azerbaijan Communist Party. The session of the Council of People's Deputies of the NKAR July 12, 1988 adopted an illegal decree on annexation of autonomous region to the Armenian SSR. July 18, 1988 The issue “About decisions of the Supreme Councils of the Armenian SSR and the Azerbaijan SSR regarding Nagorno- Karabakh” was discussed at the enlarged meeting of the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Council. -

The City of Winds

Travel by Nivine Maktabi Baku the City of Winds Heyder Aliyev Center designed by Zaha Hadid. Should I call it the City of Caviar, Oil and Gaz or the land of Caucasian Carpets? It was in May, right after Beirut Designers’ Week, when I packed a small suitcase and I am specifying small as I admit it was a big mistake to try and travel light for a change. I was flying to Baku, capital of Azerbaijan, a city which name’s always fascinated me. In fact, for me, Azerbaijan, the home of the Caucasus, is a name I only crossed in my readings Oil tanks in the middle of the sea. and specially when researching on Caucasian carpets. I headed to Fairmont Hotel, known as the Flame towers, the tallest and biggest three skyscrapers in the city. An impressive archi- 4 am was the take off; of course I was sleepy and slept on both tecture overlooking the city and the Caspian Sea was awaiting me. connecting flights, from Beirut to Istanbul and Istanbul to Baku. As it is not yet a popular touristic destination, most passengers Due to my several travels to carpet manufacturing countries, were either locals or Turkish and around one or two foreigners Azerbaijan was actually a big surprise, very different from what I I would assume working for a petroleum company, BT or alike. imagined it. While still in the taxi, at some point I thought I was in Dubai, then some of the buildings and highways reminded me of Upon arrival, the sun was blinding and a line of black cabs were filling St Petersburg and then again the boulevards resembled Paris. -

Azerbaijan Investment Guide 2015

PERSPECTIVE SPORTS CULTURE & TOURISM ICT ENERGY FINANCE CONSTRUCTION GUIDE Contents 4 24 92 HE Ilham Aliyev Sports Energy HE Ilham Aliyev, President Find out how Azerbaijan is The Caspian powerhouse is of Azerbaijan talks about the entering the world of global entering stage two of its oil future for Azerbaijan’s econ- sporting events to improve and gas development plans, omy, its sporting develop- its international image, and with eyes firmly on the ment and cultural tolerance. boost tourism. European market. 8 50 120 Perspective Culture & Finance Tourism What is modern Azerbaijan? Diversifying the sector MICE tourism, economic Discover Azerbaijan’s is key for the country’s diversification, international hospitality, art, music, and development, see how relations and building for tolerance for other cultures PASHA Holdings are at the future. both in the capital Baku the forefront of this move. and beyond. 128 76 Construction ICT Building the monuments Rapid development of the that will come to define sector will see Azerbaijan Azerbaijan’s past, present and future in all its glory. ASSOCIATE PUBLISHERS: become one of the regional Nicole HOWARTH, leaders in this vital area of JOHN Maratheftis the economy. EDITOR: 138 BENJAMIN HEWISON Guide ART DIRECTOR: JESSICA DORIA All you need to know about Baku and beyond in one PROJECT DIRECTOR: PHIL SMITH place. Venture forth and explore the ‘Land of Fire’. PROJECT COORDINATOR: ANNA KOERNER CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: MARK Elliott, CARMEN Valache, NIGAR Orujova COVER IMAGE: © RAMIL ALIYEV / shutterstock.com 2nd floor, Berkeley Square House London W1J 6BD, United Kingdom In partnership with T: +44207 887 6105 E: [email protected] LEADING EDGE AZERBAIJAN 2015 5 Interview between Leading Edge and His Excellency Ilham Aliyev, President of the Republic of Azerbaijan LE: Your Excellency, in October 2013 you received strong reserves that amount to over US $53 billion, which is a very support from the people of Azerbaijan and were re-elect- favourable figure when compared to the rest of the world. -

HEYDER ALIYEV CENTRE, Azerbaijan Zaha Hadid Architects Background in 2013, the Heydar Aliyev Center Opened to the Public in Baku, the Capital of Azerbaijan

HEYDER ALIYEV CENTRE, Azerbaijan Zaha Hadid Architects Background In 2013, the Heydar Aliyev Center opened to the public in Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan. The cultural center, designed by Zaha Hadid, has become the primary building for the nation's cultural programs, aspiring instead to express the sensibilities of Azeri culture and the optimism of a nation that looks to the future. This report presents a case study of the project. It will include the background information, a synopsis of the architect's mastery of structural design. Also, some special elements of this building will be discussed in detail. And the structural design of the whole complex will be reviewed through diagrams and the simplified computer-based structural analysis. The Heydar Aliyev Center Since 1991, Azerbaijan has been working on modernizing and developing Baku’s infrastructure and architecture in order to depart from its legacy of normative Soviet Modernism. The center is named for Heydar Aliyev, the leader of Soviet-era Azerbaijan from 1969 to 1982, and President of Azerbaijan from October 1993 to October 2003. The project is located in the center of the city. And it played an extremely important role in the development of the city. It breaks from the rigid and often monumental Soviet architecture that is so prevalent in Baku. More importantly, it is a symbol of democratic philosophy thought. Under the influence of the new Azerbaijan party and the Soviet Socialist Republic of Azerbaijan leader’s political and economic reform, the center was also designed to show the potential of the country’s future cultural development, to encourage people to study the history, language, culture, national creed and spiritual values of their own country. -

Download File

Azerbaijan Country Office COVID-19 Situation Report No. 6 Situation in Numbers Published on 15 May 2020 (as of 13 May 2020) WEEKLY HIGHLIGHTS 2,758 • As of 13 May, 2,758 cases of COVID-19 have been confirmed, with 35 deaths and COVID-19 cases 1,789 recovered cases. The number of tests carried out as of 13 May had reached 208,546. • Starting from 5 May, a gradual lifting of the special quarantine regime was applied 35 including a resumption of service on the Baku Metro from 9 May. COVID-19 deaths • UNICEF Azerbaijan continued its joint campaign for young people with the Youth Foundation on social media focusing on staying healthy while at home, with a series of posts on yoga, simple physical exercises and art. 1,789 • 70 posters and 4,780 leaflets and brochures were distributed by young 50 volunteers people recovered amongst 1,790 families in Narimanov and Azizbekov Districts of Baku, Ganja, Goranboy and settlements for internally displaced persons from Kalbajar District in partnership with Azerbaijan Red Crescent Society. • UNICEF continued developing a series of interactive webinars on Basic Life Skills (BLS 1.9 million Remote) based on its face-to-face regular 16-lesson programme for the cross-country School and pre- network of Youth Houses. Session 2 on Emotional Regulation was conducted on 7 May school aged children reaching 1,599 people through social media live streaming and online meeting and young people platforms, with 800 participants being students of Vocational Education and Training affected by schools. school closures • A live session was held on social media platforms with three local experts on child health to provide parents and caregivers of young children with necessary advice/counselling on child health, infant and maternal nutrition, breastfeeding and US$ 1,235,185 vaccination of children during the COVID-19 outbreak, organized by the Public Health Planned budget Reform Centre (PHRC) and supported by UNICEF. -

Trams Der Welt / Trams of the World 2021 Daten / Data © 2021 Peter Sohns Seite / Page 1

www.blickpunktstrab.net – Trams der Welt / Trams of the World 2021 Daten / Data © 2021 Peter Sohns Seite / Page 1 Algeria ... Alger (Algier) ... Metro ... 1435 mm Algeria ... Alger (Algier) ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Algeria ... Constantine ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Algeria ... Oran ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Algeria ... Ouragla ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Algeria ... Sétif ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Algeria ... Sidi Bel Abbès ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Argentina ... Buenos Aires, DF ... Metro ... 1435 mm Argentina ... Buenos Aires, DF - Caballito ... Heritage-Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Argentina ... Buenos Aires, DF - Lacroze (General Urquiza) ... Interurban (Electric) ... 1435 mm Argentina ... Buenos Aires, DF - Premetro E ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Argentina ... Buenos Aires, DF - Tren de la Costa ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Argentina ... Córdoba, Córdoba ... Trolleybus Argentina ... Mar del Plata, BA ... Heritage-Tram (Electric) ... 900 mm Argentina ... Mendoza, Mendoza ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Argentina ... Mendoza, Mendoza ... Trolleybus Argentina ... Rosario, Santa Fé ... Heritage-Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Argentina ... Rosario, Santa Fé ... Trolleybus Argentina ... Valle Hermoso, Córdoba ... Tram-Museum (Electric) ... 600 mm Armenia ... Yerevan ... Metro ... 1524 mm Armenia ... Yerevan ... Trolleybus Australia ... Adelaide, SA - Glenelg ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Australia ... Ballarat, VIC ... Heritage-Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Australia ... Bendigo, VIC ... Heritage-Tram