January-February 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Willi Orchids

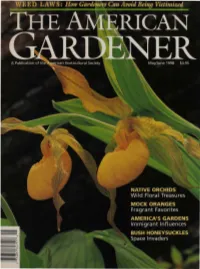

growers of distinctively better plants. Nunured and cared for by hand, each plant is well bred and well fed in our nutrient rich soil- a special blend that makes your garden a healthier, happier, more beautiful place. Look for the Monrovia label at your favorite garden center. For the location nearest you, call toll free l-888-Plant It! From our growing fields to your garden, We care for your plants. ~ MONROVIA~ HORTICULTURAL CRAFTSMEN SINCE 1926 Look for the Monrovia label, call toll free 1-888-Plant It! co n t e n t s Volume 77, Number 3 May/June 1998 DEPARTMENTS Commentary 4 Wild Orchids 28 by Paul Martin Brown Members' Forum 5 A penonal tour ofplaces in N01,th America where Gaura lindheimeri, Victorian illustrators. these native beauties can be seen in the wild. News from AHS 7 Washington, D . C. flower show, book awards. From Boon to Bane 37 by Charles E. Williams Focus 10 Brought over f01' their beautiful flowers and colorful America)s roadside plantings. berries, Eurasian bush honeysuckles have adapted all Offshoots 16 too well to their adopted American homeland. Memories ofgardens past. Mock Oranges 41 Gardeners Information Service 17 by Terry Schwartz Magnolias from seeds, woodies that like wet feet. Classic fragrance and the ongoing development of nell? Mail-Order Explorer 18 cultivars make these old favorites worthy of considera Roslyn)s rhodies and more. tion in today)s gardens. Urban Gardener 20 The Melting Plot: Part II 44 Trial and error in that Toddlin) Town. by Susan Davis Price The influences of African, Asian, and Italian immi Plants and Your Health 24 grants a1'e reflected in the plants and designs found in H eading off headaches with herbs. -

The Mock-Oranges

ARNOLDIA A continuation of the BULLETIN OF POPULAR INFORMATION of the Arnold Arboretum, Harvard University VOLUME ~Jr JUNE 18, 1965 NUMBER5 THE MOCK-ORANGES are about fifty species and varieties of Philadelphus being grown in THERE-~- the commercial nurseries of the United States, so there is a wealth of ma- terial from which to select ornamental plants. The collection at the Arnold Arboretum contams over one hundred species and varieties. They all have white flowers, their fruits are dried capsules and not very interesting, and the autumn color is not especially outstanding, being yellow or yellowish. In other words, they are chiefly of value during the short period when they are in bloom; but they are all grown easily in almost any normal soil, and are mostly free from injurious insect and disease pests-reason enough why they have proved popular over the years. Some plants in this group have special merit. Philadelphus coronarius, for in- stance, is excellent for planting in dry soil situations. Many of the hybrids have extremely fragrant flowers, and some of the plants, like P. laxus and P. X splen- dens, have branches which face the ground well all around and make fairly good foliage specimens throughout the length of time they retain their leaves. On the other hand, the flowers of many of the species are not fragrant, and some plants, like Philadelphus delavayi and P. X monstrosus reach heights of fifteen feet or more; they are frequently just too tall and vigorous for the small garden. There are better shrubs of this height with mteresting flowers, better autumn color, and fruits in the fall (like some of the viburnums), so, if tall shrubs are desired, it is not the mock-oranges which should have first consideration. -

Principles of Plant Taxonomy, V.*

THE OHIO JOURNAL OF SCIENCE VOL. XXVIII MARCH, 1928 No. 2 PRINCIPLES OF PLANT TAXONOMY, V.* JOHN H. SCHAFFNER, Ohio State University. After studying the taxonomy of plants for twenty-five years the very remarkable fact became evident that there is no general correspondence of the taxonomic system with the environment, but as the great paleontologist, Williams, said in 1895: "environmental conditions are but the medium through which organic evolution has been determinately ploughing its way." Of course, the very fact that there is a system of phylogenetic relationships of classes, orders, families, and genera and that these commonly have no general correspondence to environment shows that, in classifying the plant material, we must discard all notions of teleological, utilitarian, and selective factors as causative agents of evolution. The general progressive movement has been carried on along quite definite lines. The broader and more fundamental changes appeared first and are practically constant, and on top of these, .potentialities or properties of smaller and smaller value have been introduced, until at the end new factors of little general importance alone are evolved. These small potentialities are commonly much less stable than the more fundamental ones and thus great variability in subordinate characters is often present in the highest groups. We must then think of the highest groups as being full of hereditary potentialities while the lower groups have comparatively few. As stated above, there is a profound non-correspondence of the .taxonomic system and the various orthogenetic series with the environment. The system of plants, from the taxonomic point of view, is non-utilitarian. -

Plant Life MagillS Encyclopedia of Science

MAGILLS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE PLANT LIFE MAGILLS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE PLANT LIFE Volume 4 Sustainable Forestry–Zygomycetes Indexes Editor Bryan D. Ness, Ph.D. Pacific Union College, Department of Biology Project Editor Christina J. Moose Salem Press, Inc. Pasadena, California Hackensack, New Jersey Editor in Chief: Dawn P. Dawson Managing Editor: Christina J. Moose Photograph Editor: Philip Bader Manuscript Editor: Elizabeth Ferry Slocum Production Editor: Joyce I. Buchea Assistant Editor: Andrea E. Miller Page Design and Graphics: James Hutson Research Supervisor: Jeffry Jensen Layout: William Zimmerman Acquisitions Editor: Mark Rehn Illustrator: Kimberly L. Dawson Kurnizki Copyright © 2003, by Salem Press, Inc. All rights in this book are reserved. No part of this work may be used or reproduced in any manner what- soever or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy,recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address the publisher, Salem Press, Inc., P.O. Box 50062, Pasadena, California 91115. Some of the updated and revised essays in this work originally appeared in Magill’s Survey of Science: Life Science (1991), Magill’s Survey of Science: Life Science, Supplement (1998), Natural Resources (1998), Encyclopedia of Genetics (1999), Encyclopedia of Environmental Issues (2000), World Geography (2001), and Earth Science (2001). ∞ The paper used in these volumes conforms to the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48-1992 (R1997). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Magill’s encyclopedia of science : plant life / edited by Bryan D. -

Forcing Branches for Winter Color B

Indoor Horticulture • HO-23-W Department of Horticulture Purdue University Cooperative Extension Service • West Lafayette, IN Forcing Branches for Winter Color B. Rosie Lerner and Michael N. Dana Does the bleak, cold dullness of winter sometimes get Next, put the branches in a container which will hold you down? Then why not bring springtime into your home them upright. Add warm water (110°F) no higher than 3 by forcing tree and shrub branches into bloom? Branches inches on the stems. A flower preservative will help can be used as background for an arrangement or for an prolong the vase life of the branches (see Figure 1 for entire floral display, and you can prune your shrubs and preservative recipes). Allow to stand for 20-30 minutes, trees as you selectively remove branches for forcing. and then fill the container with additional preservative solution. Place the container in a cool (60-65°F), partially Early spring flowering trees and shrubs form their flower shaded location. Keep the water level at its original buds in the fall before the plants go dormant. After a height. period of at least 8 weeks of temperatures below 40°F (usually after January 1), branches can be cut and forced Finally, when the buds show color, move the branches to into bloom. a lighted room. But don’t put them in direct sunlight. At this time they can be removed from the storage container Most flowering shrubs are fairly easy to force, while trees and arranged in the desired manner. Be sure the ar are more difficult. -

Cytotoxicity of Water Extracts from Leaves and Branches of Philadelphus Coronarius L

Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2006, 150(1):71–73. 71 © V. Valko, M. Fickova, E. Pravdova, M. Nagy, D. Grancai, S. Czigle CYTOTOXICITY OF WATER EXTRACTS FROM LEAVES AND BRANCHES OF PHILADELPHUS CORONARIUS L. Vojtech Valkoa, Maria Fickovab, Eliska Pravdovab, Milan Nagya, Daniel Grancaia, Szilvia Cziglea a Department of Pharmacognosy and Botany, Faculty of Pharmacy, Comenius University, Odbojárov 10, 832 32 Bratislava, Slovak Republic, e-mail: [email protected] b Institute of Experimental Endocrinology SAS, Vlárska 3, 833 06 Bratislava Received: March 17, 2006; Accepted (with revisions): June 7, 2006 Keywords: Philadelphus coronarius L./Plant water extracts/A431 cells/MCF-7 cells/MTT cytotoxicity Philadelphus coronarius L. is big, leggy and deciduous old-fashioned shrub known for its fragrant white flowers in the late spring. Some members of genus Philadelphus L. are known for their antibacterial, antiradical and immuno- modulatory effects. Therefore, these herbs represent prospective sources for the isolation of active substances with desired effects. We have investigated the cytotoxicity effects of water extracts from leaves and branches of Philadelphus coronarius L. (Hydrangeaceae). A431 cells (human skin carcinoma cell line) and the human breast adenocarcinoma cell line (MCF-7) were treated with various doses of individual extracts (0,1–100 μg dry matter/ml) for 24 h and 72 h. The highest toxic effects of both plant parts extracts were observed on MCF-7 cells regardless the time of treatment. Cells A431 were less sensitive to toxic effects of leaves and branches extracts but the time dependence was present with the tendency of increased toxicity after chronic treatment. -

Flora of Vascular Plants of the Seili Island and Its Surroundings (SW Finland)

Biodiv. Res. Conserv. 53: 33-65, 2019 BRC www.brc.amu.edu.pl DOI 10.2478/biorc-2019-0003 Submitted 20.03.2018, Accepted 10.01.2019 Flora of vascular plants of the Seili island and its surroundings (SW Finland) Andrzej Brzeg1, Wojciech Szwed2 & Maria Wojterska1* 1Department of Plant Ecology and Environmental Protection, Faculty of Biology, Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Umultowska 89, 61-614 Poznań, Poland 2Department of Forest Botany, Faculty of Forestry, Poznań University of Life Sciences, Wojska Polskiego 71D, 60-625 Poznań, Poland * corresponding author (e-mail: [email protected]; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7774-1419) Abstract. The paper shows the results of floristic investigations of 12 islands and several skerries of the inner part of SW Finnish archipelago, situated within a square of 11.56 km2. The research comprised all vascular plants – growing spontaneously and cultivated, and the results were compared to the present flora of a square 10 × 10 km from the Atlas of Vascular Plants of Finland, in which the studied area is nested. The total flora counted 611 species, among them, 535 growing spontaneously or escapees from cultivation, and 76 exclusively in cultivation. The results showed that the flora of Seili and adjacent islands was almost as rich in species as that recorded in the square 10 × 10 km. This study contributed 74 new species to this square. The hitherto published analyses from this area did not focus on origin (geographic-historical groups), socioecological groups, life forms and on the degree of threat of recorded species. Spontaneous flora of the studied area constituted about 44% of the whole flora of Regio aboënsis. -

Homestead Gardens Golden Mockorange

Davidsonville MD & Severna Park MD | HomesteadGardens.com Golden Mockorange Philadelphus coronarius 'Aureus' Height: 7 feet Spread: 7 feet Sunlight: Hardiness Zone: 3b Description: Golden Mockorange flowers A beautiful and versatile shrub featuring rich golden Photo courtesy of NetPS Plant Finder foliage and fragrant white flowers in early summer, color tends to fade to yellow-green over the summer; not a profuse bloomer, use for foliage color; very adaptable and easy to grow Ornamental Features Golden Mockorange features showy clusters of fragrant white flowers with yellow eyes at the ends of the branches in late spring. It has attractive yellow foliage throughout the season. The serrated oval leaves are highly ornamental but do not develop any appreciable fall color. The fruit is not ornamentally significant. Landscape Attributes Golden Mockorange Golden Mockorange is a dense multi-stemmed deciduous Photo courtesy of NetPS Plant Finder shrub with an upright spreading habit of growth. Its average texture blends into the landscape, but can be balanced by one or two finer or coarser trees or shrubs for an effective composition. This is a relatively low maintenance shrub, and should only be pruned after flowering to avoid removing any of the current season's flowers. It has no significant negative characteristics. Golden Mockorange is recommended for the following landscape applications; - Accent - Mass Planting - Hedges/Screening - General Garden Use Davidsonville MD & Severna Park MD | HomesteadGardens.com Planting & Growing Golden Mockorange will grow to be about 7 feet tall at maturity, with a spread of 7 feet. It tends to fill out right to the ground and therefore doesn't necessarily require facer plants in front, and is suitable for planting under power lines. -

A List of the Vascular Plants of Bender Mountain Preserve (Including Parts of the Delhi Township

Ohio Biological Survey Notes 7: 21–33, 2017. © Ohio Biological Survey, Inc. A List of the Vascular Plants of Bender Mountain Preserve (Including Adjacent Parts of the Delhi Township Property and Sisters’ Hill) DENIS CONOVER1*, TIM SISSON2, DAN BOONE3, AND MARY M. RIESTENBERG4 1Dept. Biological Sciences, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH 45221-0006; 2Western Wildlife Corridor, P.O. Box 389077, Cincinnati, OH 45238; 33228 Hanna Ave., Cincinnati, OH 45211; 4Dept. of Biology, Mount St. Joseph University, 5701 Delhi Ave., Cincinnati, OH 45233. *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract: Several species of non-native invasive plants, including Amur honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii), had become quite numerous at Bender Mountain Preserve in Hamilton County, which made it very difficult for native plants to compete. After the removal of Amur honeysuckle by Western Wildlife Corridor volunteers, there was a resurgence of native plants in the preserve. So far, 431 species of vascular plants have been identified, 73% of which are native to Hamilton County. This list is sure to grow over the next few years as the preserve continues to recover. It is hoped that this study will encourage land managers and park districts not to give up on their nature preserves: non-native, invasive plants can be controlled in natural areas and native plants can come back. Key Words: Amur honeysuckle, native plants, Western Wildlife Corridor, Western Mesophytic Forest Region, Ohio River Valley Introduction Bender Mountain Nature Preserve (N 39.10º, W 084.67º) is a 22.3 ha preserve in southwest Hamilton County, Ohio, consisting of property owned by Delhi Township Parks and Recreation as well as land owned by the Western Wildlife Corridor. -

Hydrangeaceae – Mock-Orange Family

HYDRANGEACEAE – MOCK-ORANGE FAMILY Plant: vines, herbs or shrubs Stem: Root: Leaves: deciduous or evergreen; alternate or opposite, glands or not; no stipules Flowers: perfect, mostly regular (actinomorphic), some irregular; sepals and petals mostly 4-5 (-10); stamens 4 to many; ovary mostly inferior, many ovules Fruit: mostly a capsule or berry Other: some include in Family Saxifragaceae (Hydrangeoidea or Hydrangeaceae subfamily); Dicotyledons Group Genera: 10+ genera; locally Hydrangea, Philadelphus WARNING – family descriptions are only a layman’s guide and should not be used as definitive HYDRANGEACEAE – MOCK-ORANGE FAMILY Wild Hydrangea; Hydrangea arborescens L. Five Petal Cliffbush [Waxflower]; Jamesia americana Torr. & A. Gray var. Americana Sweet [Garden] Mock Orange; Philadelphus coronarius L. [Introduced] Wild Hydrangea USDA Hydrangea arborescens L. Hydrangeaceae (Mock Orange Family) Alley Springs, Ozark National Riverways, Shannon County, Missouri Notes: shrub; 4-petaled flower, white, larger marginal flowers often sterile, 8 stamens, in terminal panicle; leaves, opposite, ovate, toothed, with sharp point, long petioles; mostly in moist woods; summer (several varieties) [V Max Brown, 2007] Five Petal Cliffbush [Waxflower] USDA Jamesia americana Torr. & A. Gray var. Americana Hydrangeaceae (Mock Orange Family) Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado Notes: shrub; mostly 5-petaled flower, white, about 2 cm in diameter, sepals greenish, hairy, in clusters (panicles); leaves opposite, ovate with sharp tip, serrate, glossy above -

Japansese Beetle Potential Host Range

Japanese Beetle Potential Host Range in California D. G. Kelch, Ph.D. Primary Botanist, California Department of Food and Agriculture Japanese Beetle (Popillia japonica Newman) is a species introduced into North America that has spread widely throughout the eastern United States. In this area, infestations have proven extremely damaging to horticultural and agricultural plants. Yearly costs for management and mitigation of damage are estimated at US$500 million (USDA 2007). In addition, areas infested with Japanese beetle can be quarantined by trading partners, resulting in losses to farmers and nursery growers mounting into the millions of dollars per year (National Plant Board 2007; Smith et al. 1996). Japanese Beetle is not yet fully established in California, but recent detections in Sacramento County have raised concerns and triggered control activities by agencies tasked with protecting plants from pests. Japanese beetles have a broad range of host plants. The list of plants used as hosts by Japanese beetle contains more than 300 species (Potter & Held 2002). Because the focus has been on Japanese beetle attacks in gardens and lawns, the host list is dominated by garden plants. Most of the information on host susceptibility to Japanese beetle originated from a landmark survey summariZed by Fleming (1972). This rating system was based on written and oral accounts of Japanese beetle feeding damage noted from 1920 through 1963 primarily in the New England area (Fleming 1972). Although poorly documented, there is little doubt that Japanese beetle can attack many other species of plants not included on the host list (Miller et al., 2001; Potter & Held 2002). -

Southern Garden History Plant Lists

Southern Plant Lists Southern Garden History Society A Joint Project With The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation September 2000 1 INTRODUCTION Plants are the major component of any garden, and it is paramount to understanding the history of gardens and gardening to know the history of plants. For those interested in the garden history of the American south, the provenance of plants in our gardens is a continuing challenge. A number of years ago the Southern Garden History Society set out to create a ‘southern plant list’ featuring the dates of introduction of plants into horticulture in the South. This proved to be a daunting task, as the date of introduction of a plant into gardens along the eastern seaboard of the Middle Atlantic States was different than the date of introduction along the Gulf Coast, or the Southern Highlands. To complicate maters, a plant native to the Mississippi River valley might be brought in to a New Orleans gardens many years before it found its way into a Virginia garden. A more logical project seemed to be to assemble a broad array plant lists, with lists from each geographic region and across the spectrum of time. The project’s purpose is to bring together in one place a base of information, a data base, if you will, that will allow those interested in old gardens to determine the plants available and popular in the different regions at certain times. This manual is the fruition of a joint undertaking between the Southern Garden History Society and the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. In choosing lists to be included, I have been rather ruthless in expecting that the lists be specific to a place and a time.