Principles of Plant Taxonomy, V.*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BIOL/APBI 324 – Introduction to Seed Plant Taxonomy

This syllabus is a general representation of the course as previously offered and is subject to change. BIOL/APBI 324 – Introduction to Seed Plant Taxonomy General Course Syllabus (as of September 2019) About the Course: Course Description: An introduction to seed plant taxonomy emphasizing descriptive morphology and identification. Each student will be required to submit a plant collection. Correct understanding of the actual relationships between plants, rather than superficial resemblance, is the basis of comparative biology required to analyze the diversity of plant forms. The species diversity of plants is considerable, and this course will pay particular attention to very diverse and important groups such as the grasses and the orchids, focusing on reasons for their evolutionary success. Identification skills will be inculcated by the lectures working in tandem with the laboratory sessions. This course aims to give students a good working knowledge of plant taxonomy as a preparation for work in any biological discipline. Course Format: Lecture and Laboratory Credits: 3 Pre-requisites: BIOL 121 Course Learning Objectives: By the end of this course, students will be able to: • Achieve a good working knowledge of concepts, principles, and recent discoveries in plant taxonomy. • Gain an overview of seed plant diversity, including the most species-rich plant families and so be able to place any botanical information in the overall context of plant diversity. • Learn ways in which their knowledge can be applied to ecology and evolutionary biology. • Gain an appreciation of how current research in the field is being done by reading recent research papers. Textbooks and Additional Resources: Laboratory fee: $25; please bring to first lab. -

A Checklist of the Vascular Flora of the Mary K. Oxley Nature Center, Tulsa County, Oklahoma

Oklahoma Native Plant Record 29 Volume 13, December 2013 A CHECKLIST OF THE VASCULAR FLORA OF THE MARY K. OXLEY NATURE CENTER, TULSA COUNTY, OKLAHOMA Amy K. Buthod Oklahoma Biological Survey Oklahoma Natural Heritage Inventory Robert Bebb Herbarium University of Oklahoma Norman, OK 73019-0575 (405) 325-4034 Email: [email protected] Keywords: flora, exotics, inventory ABSTRACT This paper reports the results of an inventory of the vascular flora of the Mary K. Oxley Nature Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma. A total of 342 taxa from 75 families and 237 genera were collected from four main vegetation types. The families Asteraceae and Poaceae were the largest, with 49 and 42 taxa, respectively. Fifty-eight exotic taxa were found, representing 17% of the total flora. Twelve taxa tracked by the Oklahoma Natural Heritage Inventory were present. INTRODUCTION clayey sediment (USDA Soil Conservation Service 1977). Climate is Subtropical The objective of this study was to Humid, and summers are humid and warm inventory the vascular plants of the Mary K. with a mean July temperature of 27.5° C Oxley Nature Center (ONC) and to prepare (81.5° F). Winters are mild and short with a a list and voucher specimens for Oxley mean January temperature of 1.5° C personnel to use in education and outreach. (34.7° F) (Trewartha 1968). Mean annual Located within the 1,165.0 ha (2878 ac) precipitation is 106.5 cm (41.929 in), with Mohawk Park in northwestern Tulsa most occurring in the spring and fall County (ONC headquarters located at (Oklahoma Climatological Survey 2013). -

Willi Orchids

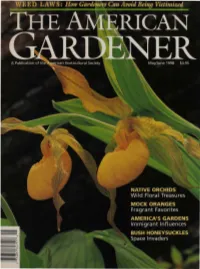

growers of distinctively better plants. Nunured and cared for by hand, each plant is well bred and well fed in our nutrient rich soil- a special blend that makes your garden a healthier, happier, more beautiful place. Look for the Monrovia label at your favorite garden center. For the location nearest you, call toll free l-888-Plant It! From our growing fields to your garden, We care for your plants. ~ MONROVIA~ HORTICULTURAL CRAFTSMEN SINCE 1926 Look for the Monrovia label, call toll free 1-888-Plant It! co n t e n t s Volume 77, Number 3 May/June 1998 DEPARTMENTS Commentary 4 Wild Orchids 28 by Paul Martin Brown Members' Forum 5 A penonal tour ofplaces in N01,th America where Gaura lindheimeri, Victorian illustrators. these native beauties can be seen in the wild. News from AHS 7 Washington, D . C. flower show, book awards. From Boon to Bane 37 by Charles E. Williams Focus 10 Brought over f01' their beautiful flowers and colorful America)s roadside plantings. berries, Eurasian bush honeysuckles have adapted all Offshoots 16 too well to their adopted American homeland. Memories ofgardens past. Mock Oranges 41 Gardeners Information Service 17 by Terry Schwartz Magnolias from seeds, woodies that like wet feet. Classic fragrance and the ongoing development of nell? Mail-Order Explorer 18 cultivars make these old favorites worthy of considera Roslyn)s rhodies and more. tion in today)s gardens. Urban Gardener 20 The Melting Plot: Part II 44 Trial and error in that Toddlin) Town. by Susan Davis Price The influences of African, Asian, and Italian immi Plants and Your Health 24 grants a1'e reflected in the plants and designs found in H eading off headaches with herbs. -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

The Mock-Oranges

ARNOLDIA A continuation of the BULLETIN OF POPULAR INFORMATION of the Arnold Arboretum, Harvard University VOLUME ~Jr JUNE 18, 1965 NUMBER5 THE MOCK-ORANGES are about fifty species and varieties of Philadelphus being grown in THERE-~- the commercial nurseries of the United States, so there is a wealth of ma- terial from which to select ornamental plants. The collection at the Arnold Arboretum contams over one hundred species and varieties. They all have white flowers, their fruits are dried capsules and not very interesting, and the autumn color is not especially outstanding, being yellow or yellowish. In other words, they are chiefly of value during the short period when they are in bloom; but they are all grown easily in almost any normal soil, and are mostly free from injurious insect and disease pests-reason enough why they have proved popular over the years. Some plants in this group have special merit. Philadelphus coronarius, for in- stance, is excellent for planting in dry soil situations. Many of the hybrids have extremely fragrant flowers, and some of the plants, like P. laxus and P. X splen- dens, have branches which face the ground well all around and make fairly good foliage specimens throughout the length of time they retain their leaves. On the other hand, the flowers of many of the species are not fragrant, and some plants, like Philadelphus delavayi and P. X monstrosus reach heights of fifteen feet or more; they are frequently just too tall and vigorous for the small garden. There are better shrubs of this height with mteresting flowers, better autumn color, and fruits in the fall (like some of the viburnums), so, if tall shrubs are desired, it is not the mock-oranges which should have first consideration. -

Aquatic Vascular Plant Species Distribution Maps

Appendix 11.5.1: Aquatic Vascular Plant Species Distribution Maps These distribution maps are for 116 aquatic vascular macrophyte species (Table 1). Aquatic designation follows habitat descriptions in Haines and Vining (1998), and includes submergent, floating and some emergent species. See Appendix 11.4 for list of species. Also included in Appendix 11.4 is the number of HUC-10 watersheds from which each taxon has been recorded, and the county-level distributions. Data are from nine sources, as compiled in the MABP database (plus a few additional records derived from ancilliary information contained in reports from two fisheries surveys in the Upper St. John basin organized by The Nature Conservancy). With the exception of the University of Maine herbarium records, most locations represent point samples (coordinates were provided in data sources or derived by MABP from site descriptions in data sources). The herbarium data are identified only to township. In the species distribution maps, town-level records are indicated by center-points (centroids). Figure 1 on this page shows as polygons the towns where taxon records are identified only at the town level. Data Sources: MABP ID MABP DataSet Name Provider 7 Rare taxa from MNAP lake plant surveys D. Cameron, MNAP 8 Lake plant surveys D. Cameron, MNAP 35 Acadia National Park plant survey C. Greene et al. 63 Lake plant surveys A. Dieffenbacher-Krall 71 Natural Heritage Database (rare plants) MNAP 91 University of Maine herbarium database C. Campbell 183 Natural Heritage Database (delisted species) MNAP 194 Rapid bioassessment surveys D. Cameron, MNAP 207 Invasive aquatic plant records MDEP Maps are in alphabetical order by species name. -

Plant Life MagillS Encyclopedia of Science

MAGILLS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE PLANT LIFE MAGILLS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE PLANT LIFE Volume 4 Sustainable Forestry–Zygomycetes Indexes Editor Bryan D. Ness, Ph.D. Pacific Union College, Department of Biology Project Editor Christina J. Moose Salem Press, Inc. Pasadena, California Hackensack, New Jersey Editor in Chief: Dawn P. Dawson Managing Editor: Christina J. Moose Photograph Editor: Philip Bader Manuscript Editor: Elizabeth Ferry Slocum Production Editor: Joyce I. Buchea Assistant Editor: Andrea E. Miller Page Design and Graphics: James Hutson Research Supervisor: Jeffry Jensen Layout: William Zimmerman Acquisitions Editor: Mark Rehn Illustrator: Kimberly L. Dawson Kurnizki Copyright © 2003, by Salem Press, Inc. All rights in this book are reserved. No part of this work may be used or reproduced in any manner what- soever or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy,recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address the publisher, Salem Press, Inc., P.O. Box 50062, Pasadena, California 91115. Some of the updated and revised essays in this work originally appeared in Magill’s Survey of Science: Life Science (1991), Magill’s Survey of Science: Life Science, Supplement (1998), Natural Resources (1998), Encyclopedia of Genetics (1999), Encyclopedia of Environmental Issues (2000), World Geography (2001), and Earth Science (2001). ∞ The paper used in these volumes conforms to the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48-1992 (R1997). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Magill’s encyclopedia of science : plant life / edited by Bryan D. -

Principles of Plant Taxonomy Bot

PRINCIPLES OF PLANT TAXONOMY BOT 222 Dr. M. Ajmal Ali, PhD 1 What is Taxonomy / Systematics ? Animal group No. of species Amphibians 6,199 Birds 9,956 Fish 30,000 Mammals 5,416 Tundra Reptiles 8,240 Subtotal 59,811 Grassland Forest Insects 950,000 Molluscs 81,000 Q: Why we keep the stuffs of our home Crustaceans 40,000 at the fixed place or arrange into some Corals 2,175 kinds of system? Desert Others 130,200 Rain forest Total 1,203,375 • Every Human being is a Taxonomist Plants No. of species Mosses 15,000 Ferns and allies 13,025 Gymnosperms 980 Dicotyledons 199,350 Monocotyledons 59,300 Green Algae 3,715 Red Algae 5,956 Lichens 10,000 Mushrooms 16,000 Brown Algae 2,849 Subtotal 28,849 Total 1,589,361 • We have millions of different kind of plants, animals and microorganism. We need to scientifically identify, name and classify all the living organism. • Taxonomy / Systematics is the branch of science deals with classification of organism. 2 • Q. What is Plant Taxonomy / Plant systematics We study plants because: Plants convert Carbon dioxide gas into Every things we eat comes Plants produce oxygen. We breathe sugars through the process of directly or indirectly from oxygen. We cannot live without photosynthesis. plants. oxygen. Many chemicals produced by the Study of plants science helps to Study of plants science helps plants used as learn more about the natural Plants provide fibres for paper or fabric. to conserve endangered medicine. world plants. We have millions of different kind of plants, animals and microorganism. -

Cupressaceae Et Taxodiaceae

AVERTISSEMENT Ce document est le fruit d'un long travail approuvé par le jury de soutenance et mis à disposition de l'ensemble de la communauté universitaire élargie. Il est soumis à la propriété intellectuelle de l'auteur. Ceci implique une obligation de citation et de référencement lors de l’utilisation de ce document. D'autre part, toute contrefaçon, plagiat, reproduction illicite encourt une poursuite pénale. Contact : [email protected] LIENS Code de la Propriété Intellectuelle. articles L 122. 4 Code de la Propriété Intellectuelle. articles L 335.2- L 335.10 http://www.cfcopies.com/V2/leg/leg_droi.php http://www.culture.gouv.fr/culture/infos-pratiques/droits/protection.htm ""&"$9 %%"'$%4$"'&%4$",,%&!($"!! !& "' !%&!""% >:<? +% #$,%!&,#"'$6"&!&"!'$ & !,"%!% #$ ' ! # # ##$ $&'$$$% 4!($%&,&$%"'$ "! /% %%%&!&#$"%%'$4!($%&,,%4""! $!$ &'+$ $"%%'$4!($%&, "$$! $!$" * -&$"!,$!%4!($%&, )"!8 ) "! % $,$$% 4!($%&, "$$! % !! '&( -&$"!,$!%4!($%&, "$$! ,"%%"'$% >:<?4!($%&, "$$!4 #'%!%5'&&% >79:?4<;<7=!0'($5+%5 !)4$! "E+$*4#-* PMNQ%))%+()A (#(")(*+())+)))+"%(*%( "*"$+G+L>(4C%))%+()H&+) '+)(%$%$#E,%(+""+)$ "E+$*4&%+((4")(***3)A (#(,,#$*#)+-(*+()*3).#%$ ")*$$ +*,"">'+ #E%$* &(#) (4")( *(," *3)A ) $%)) &&($$$*"+($$'+D E> *$)0-&(#(#)$3( (**+ &%+( "+( %$$> "+( )%+*$> "+( &*$ * "+( 4)$*4())#$* &%+( " *($)#))%$%$$))$$)$)+($*")'+*($$4)A (#(4"#$**%+)")##()+ +(.'+%$*&*4%$$("+(-&(*) &%+(4,"+(*(,"A (0"&(* %$! 7)!>#)(&&%(*+()$)'+J0 -

Botsad 03 2018.Indd

БЮЛЛЕТЕНЬ ГЛАВНОГО БОТАНИЧЕСКОГО САДА 3/2018 (Выпуск 204) ISSN: 0366-502Х СОДЕРЖАНИЕ Учредители: Федеральное государственное ИНТРОДУКЦИЯ И АККЛИМАТИЗАЦИЯ бюджетное учреждение науки Главный ботанический сад им. Н.В. Цицина РАН ООО «Научтехлитиздат»; ООО «Мир журналов». Издатель: Фирсов Г.А. ООО «Научтехлитиздат» Журнал зарегистрирован федеральной службой по надзору в сфере связи Представители рода тисс (Taxus L.) в Ботаническом саду Петра Великого .........3 информационных технологий и массовых коммуникаций (Роскомнадзор). Шейко В.В. Свидетельство о регистрации СМИ ПИ № ФС77-46435 Lonicera chamissoi Bunge ex P.Kir. в природе и культуре ......................................12 Подписные индексы ОАО «Роспечать» 83164 «Пресса России» 11184 Волчанская А.В., Фирсов Г.А. Главный редактор: Демидов А.С., доктор биологических Долговечность и устойчивость редких древесных растений флоры наук, профессор, Россия Редакционная коллегия: России в Ботаническом саду Петра Великого .......................................................19 Бондорина И.А. доктор биол. наук, Россия Виноградова Ю.К. доктор биол. наук Россия Горбунов Ю.Н. доктор биол. наук, Сахарова С.Г., Орлова Л.В., Тарасевич В.Ф. (зам. гл. редактора), Россия Иманбаева А.А. канд. биол. наук, Казахстан Молканова О.И. канд. с/х наук, Россия К уточнению таксономии видов коллекции ботанического сада Плотникова Л.С. доктор биол. наук, проф. Россия Решетников В.Н. доктор биол. наук, СПбГЛТА (на примере Pseudolarix amabilis (J. Nelson) Rehder )..........................27 проф., Беларусь Романов М.С. канд.биол.наук, Россия Семихов В.Ф. доктор биол.наук, проф. Россия Кабанов А.В. Ткаченко О.Б. доктор биол. наук, Россия Шатко В.Г. канд. биол. наук (отв. секретарь), Россия Особенности формирования коллекции астильбы в ГБС РАН ............................40 Швецов А.Н. канд. биол. наук, Россия Huang Hongwen Prof., China Peter Wyse Jackson Dr., Prof.,USA Бугаев В.В. -

January-February 2019

An E-mail Gardening Newsletter from Cornell Cooperative Extension of Rensselaer, Albany and Schenectady Counties January/ February 2019 Volume 14, Number 1 Root Concerns Notes from the underground A Pear of Problems A bike ride from the Port of Albany to Voor- heesville on the recently-completed Hudson/ Helderberg Bike Trail is a true treat. While zipping by waterfalls, behind strip malls and over traffic-choked roadways on a smooth ribbon through the countryside, I say a sin- cere thank you to all those who made this joy ride possible. I have only one gripe. At the western end, in front of a lovely pavilion, are planted two Callery pears. Unfortunately, someone doesn’t know that, for some time now, Callery pear has been a plant non grata, the poster child of a bad botanical actor, and simply not a good choice for a newly designed landscape. It didn’t start out this way. According to the Washington Post, Callery pear (Pyrus Calleryana) was imported from China more than a century ago as a possible solution to the problem of fireblight disease in fruit-producing pear trees. As part of that research, thousands of Callery pear seedlings Cornell Cooperative Extension provides were growing at the U.S. Plant Introduction Station in Glenn Dale, Mary- equal program and employment opportu- land in the early 1950’s. That’s when horticulturist John Creech found one nities. Please contact that showed some outstanding ornamental characteristics. He admired its Cornell Cooperative Extension if you have beautiful early spring blossoms, disease and insect resistance, and tremen- special needs. -

Kurt Vonnegut's Mission in Galapagos

THE DAWN JOURNAL VOL. 3, NO. 1, JANUARY - JUNE 2014 A RESTATEMENT OF DARWINISM IN A NEW WORLD – KURT VONNEGUT’S MISSION IN GALAPAGOS S. Priyadarshini ABSTRACT Darwin’s Theory of Natural Selection and Theory of Evolution find a new treatment in Kurt Vonnegut’s novel Galapagos. The story of the novel is told by a ghost that watched human (d) evolution from 1986 for a million years. Pan-human beings have died through manmade and natural disasters. The survivors adapt themselves to the environment and evolved themselves with fur, flippers and streamlined heads so that they can swim in cold water easily. Through this story Vonnegut has not just reinforced Darwinism but has restated it in his own style. Galapagos is Vonnegut’s eleventh novel, and it is a wry account of the fate of human species told from a million years in the future by the ghost of the son of the Vonnegut’s alter-ego Kilgore Trout. This novel of Vonnegut is, in a way, a tribute to Darwin’s On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. The setting of the novel is the natural home of marine iguanas and larcenous frigate birds. Galapagos is itself, the same island visited by Charles Darwin in his process of exploration of the Theory of Natural Selection. The theme of the novel is also evolution. Therefore, Vonnegut’s Galapagos goes parallel to the Theory of Darwin’s Natural Selection. This paper attempts to explore Galapagos as a restatement of Darwinism in a new world rather than reinforcement.