The Booth Newspapers Lansing Bureau: an Interpretive History, 1928 to 1986

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

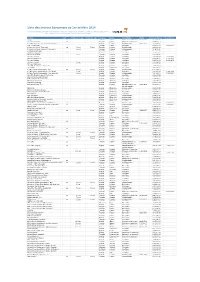

Liste Des Sources Europresse Au 1Er Octobre 2016

Liste des sources Europresse au 1er octobre 2016 Document confidentiel, liste sujette à changement, les embargos sont imposés par les éditeurs, le catalogue intégral est disponible en ligne : www.europresse.com puis "sources" et "nos sources en un clin d'œil" Source Pdf Embargo texte Embargo pdf Langue Pays Périodicité ISSN Début archives Fin archives 01 net oui Français France Mensuel ou bimensuel 1276-519X 2005/01/10 01 net - Hors-série oui Français France Mensuel ou bimensuel 2014/04/01 100 Mile House Free Press (South Cariboo) Anglais Canada Hebdomadaire 0843-0403 2008/04/09 18h, Le (site web) Français France Quotidien 2006/01/04 2014/02/18 2 Rives, Les (Sorel-Tracy, QC) oui 7 jours 7 jours Français Canada Hebdomadaire 2013/04/09 2 Rives, Les (Sorel-Tracy, QC) (site web) 7 jours Français Canada Hebdomadaire 2004/01/06 20 Minutes (site web) Français France Quotidien 2006/01/30 24 Heures (Suisse) oui Français Suisse Quotidien 2005/07/07 24 heures Montréal 1 jour Français Canada Quotidien 2012/04/04 24 hours Calgary Anglais Canada Quotidien 2012/04/05 2013/08/02 24 hours Edmonton Anglais Canada Quotidien 2012/04/05 2013/08/02 24 hours Ottawa Anglais Canada Quotidien 2012/04/02 2013/08/02 24 hours Toronto 1 jour Anglais Canada Quotidien 2012/04/05 24 hours Vancouver 1 jour Anglais Canada Quotidien 2012/04/05 24 x 7 News (Bahrain) (web site) Anglais Bahreïn Quotidien 2016/09/04 3BL Media Anglais États-Unis En continu 2013/08/23 40-Mile County Commentator, The oui 7 jours 7 jours Anglais Canada Hebdomadaire 2001/09/04 40-Mile County Commentator, The (blogs) 1 jour Anglais Canada Quotidien 2012/05/08 2016/05/31 40-Mile County Commentator, The (web site) 7 jours Anglais Canada Hebdomadaire 2011/03/02 2016/05/31 98.5 FM (Montréal, QC) (réf. -

Not for Immediate Release

Contact: Name Dan Gaydou Email [email protected] Phone 616-222-5818 DIGITAL NEWS AND INFORMATION COMPANY, MLIVE MEDIA GROUP ANNOUNCED TODAY New Company to Serve Communities Across Michigan with Innovative Digital and Print Media Products. Key Support Services to be provided by Advance Central Services Michigan. Grand Rapids, Michigan – Nov. 2, 2011 – Two new companies – MLive Media Group and Advance Central Services Michigan – will take over the operations of Booth Newspapers and MLive.com, it was announced today by Dan Gaydou, president of MLive Media Group. The Michigan-based entities, which will begin operating on February 2, 2012, will serve the changing news and information needs of communities across Michigan. MLive Media Group will be a digital-first media company that encompasses all content, sales and marketing operations for its digital and print properties in Michigan, including all current newspapers (The Grand Rapids Press, The Muskegon Chronicle, The Jackson Citizen Patriot, The Flint Journal, The Bay City Times, The Saginaw News, Kalamazoo Gazette, AnnArbor.com, Advance Weeklies) and the MLive.com and AnnArbor.com web sites. “The news and advertising landscape is changing fast, but we are well-positioned to use our talented team and our long record of journalistic excellence to create a dynamic, competitive, digitally oriented news operation,” Gaydou said. “We will be highly responsive to the changing needs of our audiences, and deliver effective options for our advertisers and business partners. We are excited about our future and confident this new company will allow us to provide superior news coverage to our readers – online, on their phone or tablet, and in print. -

Cranbrook and the British Arts & Crafts Movement: George Booth's Legacy

Cranbrook and the British Arts & Crafts Movement: George Booth's Legacy CRANBROOK ART MUSEUM MAY 24-SEPTEMBER 28, 2003 CRANBROOK AND THE BRITISH ARTS & CRAFTS MOVEMENT: GEORGE BOOTH'S LEGACY presents Cranbrook's collection of British Arts & Crafts Movement objects collected by Cranbrook's founder, the newspaper publisher George Gough Booth (1864-1949). An anglophile and metals artisan, Booth greatly admired the father of the Arts & Crafts Movement, William Morris (1834-1896), and agreed with Morris' belief that the only way art and design could progress was through arts reform and education. Booth's admiration for Morris manifests itself in his participation in the founding of the Detroit Society of Arts & Crafts in June 1906, and his subsequent role as the Society's first president. Through this venue, Booth began a long career in arts patronage that involved supporting and educating artists and subsequently exhibiting their works in order to expose the public to the highest forms of art. Later, Booth established Cranbrook Educational Community based on Morris' philosophy that all the arts should have equal recognition, be it metalwork or painting, and that artwork was an integral part of a healthy life. The majority of the objects in this exhibition were purchased and later donated by Booth, with other objects coming into the collection of Cranbrook Art Museum as a result of the strength of Booth's vision to create an Arts & Crafts utopia in the United States in order to foster new art and design. BRITISH ARTS & CRAFTS IN DETROIT William Morris believed that the 1 industrial revolution of the l9 h century had led to poorly designed objects with unnecessary applied decoration that concealed an object's use and materials of construction. -

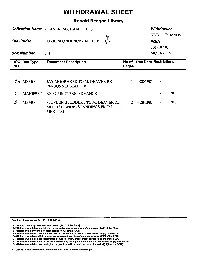

APRIL 1981 :Ii FOIA Fol-107/01 Box Number 7618 MCCARTIN 10 DOC Doc Type Document Description No of Doc Date Restrictions NO Pages

WITHDRAWAL SHEET Ronald Reagan Library Collection Name DEAVER, MICHAEL: FILES Withdrawer KDB 7/18/2005 File Folder CORRESPONDENCE-APRIL 1981 :ii FOIA FOl-107/01 Box Number 7618 MCCARTIN 10 DOC Doc Type Document Description No of Doc Date Restrictions NO Pages i) MEMO JAY MOORHEAD TO M. DEAVER RE 1 4/28/1981 B6 PERSONNEL MATTER 2 MANIFEST RE SUMMIT PRE-ADVANCE 1 B6 B7(C) I®\ MEMO STEPHEN STUDDERT TOM. DEAVER RE 2 4/28/1981 B2 B7(E) MUTUAL UNDERSTANDINGS FROM MEETING Freedom of Information Act· [5 U.S.C. 552(b)) B·1 National security classified Information [(b)(1) of the FOIA] B-2 Release would disclose Internal personnel rules and practices of an agency [(b)(2) of the FOIA] B-3 Release would violate a Federal statute [(b)(3) of the FOIA] B-4 Release would disclose trade secrets or confidential or financial Information [(b)(4) of the FOIA] B-6 Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of personal privacy [(b)(6) of the FOIA] B-7 Release would disclose information compiled for law enforcement purposes [(b)(7) of the FOIA] B-8 Release would disclose Information concerning the regulation of financial Institutions [(b)(B) of the FOIA] B-9 Release would disclose geological or geophysical Information concerning wells [(b)(9) of the FOIA] C. Closed in accordance with restrictions contained in donor's deed of gift. THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON April 28, 1981 l - ;". Dear Mr. Epple: Thank you for your kind letter and ex pression of continued support of President Reagan and his staff. -

Adopted Grosse Pointe Estate Historic District Preliminary Study

PRELIMINARY HISTORIC DISTRICT STUDY COMMITTEE REPORT GROSSE POINTE ESTATE HISTORIC DISTRICT GROSSE POINTE, MICHIGAN Adopted FEBRUARY 15, 2021 CHARGE OF THE HISTORIC DISTRICT STUDY COMMITTEE The historic district study committee was appointed by the Grosse Pointe City Council on December 14, 2020, pursuant to PA 169 of 1970 as amended. The study committee was charged with conducting an inventory, research, and preparation of a preliminary historic district study committee report for the following areas of the city: o Lakeland Ave from Maumee to Lake St. Clair o University Place from Maumee to Jefferson o Washington Road from Maumee to Jefferson o Lincoln Road from Maumee to Jefferson o Entirety of Rathbone Place o Entirety of Woodland Place o The lakefront homes and property immediately adjacent to the lakefront homes on Donovan Place, Wellington Place, Stratford Place, and Elmsleigh Place Upon completion of the report the study committee is charged with holding a public hearing and making a recommendation to city council as to whether a historic district ordinance should be adopted, and a local historic district designated. A list of study committee members and their qualifications follows. STUDY COMMITTEE MEMBERS George Bailey represents the Grosse Pointe Historical Society on the committee. He is an architect and has projects in historic districts in Detroit; Columbus, OH; and Savannah, GA. He is a history aficionado and serves on the Grosse Pointe Woods Historic Commission and Planning Commission. Kay Burt-Willson is the secretary of the Rivard Park Home Owners Association and the Vice President of Education for the Grosse Pointe Historical Society. -

A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-2006 Democracy, Hegemony, and Consent: A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language Michael Alan Glassco Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Glassco, Michael Alan, "Democracy, Hegemony, and Consent: A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language" (2006). Master's Theses. 4187. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4187 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEMOCRACY, HEGEMONY, AND CONSENT: A CRITICAL IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF MASS MEDIA TED LANGUAGE by Michael Alan Glassco A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College in partial fulfillment'of the requirements for the Degreeof Master of Arts School of Communication WesternMichigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 2006 © 2006 Michael Alan Glassco· DEMOCRACY,HEGEMONY, AND CONSENT: A CRITICAL IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF MASS MEDIATED LANGUAGE Michael Alan Glassco, M.A. WesternMichigan University, 2006 Accepting and incorporating mediated political discourse into our everyday lives without conscious attention to the language used perpetuates the underlying ideological assumptions of power guiding such discourse. The consequences of such overreaching power are manifestin the public sphere as a hegemonic system in which freemarket capitalism is portrayed as democratic and necessaryto serve the needs of the public. This thesis focusesspecifically on two versions of the Society of ProfessionalJournalist Codes of Ethics 1987 and 1996, thought to influencethe output of news organizations. -

DETROIT-METRO REGION Detroit News Submit Your Letter At: Http

DETROIT-METRO REGION Press and Guide (Dearborn) Email your letter to: Detroit News [email protected] Submit your letter at: http://content- static.detroitnews.com/submissions/letters/s Livonia Observer ubmit.htm Email your letter to: liv- [email protected] Detroit Free Press Email your letter to: [email protected] Plymouth Observer Email your letter to: liv- Detroit Metro Times [email protected] Email your letter to: [email protected] The Telegram Newspaper (Ecorse) Gazette Email your letter to: Email your letter to: [email protected] [email protected] Belleville Area Independent The South End Submit your letter at: Email your letter to: [email protected] http://bellevilleareaindependent.com/contact -us/ Deadline Detroit Email your letter to: Oakland County: [email protected] Birmingham-Bloomfield Eagle, Farmington Wayne County: Press, Rochester Post, Troy Times, West Bloomfield Beacon Dearborn Heights Time Herald/Down River Email your letter to: Sunday Times [email protected] Submit your letter to: http://downriversundaytimes.com/letter-to- Royal Oak Review, Southfield Sun, the-editor/ Woodward Talk Email your letter to: [email protected] The News-Herald Email your letter to: Daily Tribune (Royal Oak) [email protected] Post your letter to this website: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQL Grosse Pointe Times SfyWhN9s445MdJGt2xv3yyaFv9JxbnzWfC Email your letter to: [email protected] OLv9tDeuu3Ipmgw/viewform?c=0&w=1 Grosse Pointe News Lake Orion Review Email your -

Law and the Emerging Profession of Photography in the Nineteenth-Century United States

Photography Distinguishes Itself: Law and the Emerging Profession of Photography in the Nineteenth-Century United States Lynn Berger Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Lynn Berger All rights reserved ABSTRACT Photography Distinguishes Itself: Law and the Emerging Profession of Photography in the 19th Century United States Lynn Berger This dissertation examines the role of the law in the development of photography in nineteenth century America, both as a technology and as a profession. My central thesis is that the social construction of technology and the definition of the photographic profession were interrelated processes, in which legislation and litigation were key factors: I investigate this thesis through three case studies that each deal with a (legal) controversy surrounding the new medium of photography in the second half of the nineteenth century. Section 1, “Peer Production” at Mid-Century, examines the role of another relatively new medium in the nineteenth century – the periodical press – in forming, defining, and sustaining a nation-wide community of photographers, a community of practice. It argues that photography was in some ways similar to what we would today recognize as a “peer produced” technology, and that the photographic trade press, which first emerged in the early 1850s, was instrumental in fostering knowledge sharing and open innovation among photographers. It also, from time to time, served as a site for activism, as I show in a case study of the organized resistance against James A. -

ITINERARY TSKW Detroit Arts Trip FINAL 18.5.30

FINAL ITINERARY FOR 2018 TSKW ARTS & CULTURE TRIP TO DETROIT Monday 20 August thro Friday 24 August Day 1 – Mon Aug 20 Travel to destination Check in at the Detroit Foundation Hotel, Larned Street, Detroit 313-915-4422 www.detroitfoundationhotel.com 5:45pm Welcome cocktail party and private dinner at Hotel With presentation by Local Art Historian to provide background for our week of Arts & Culture in Detroit Day 2 – Tue Aug 21 Breakfast – on your own 8:45 walk to trolley station at Congress at Woodward to Detroit Institute for the Arts 9:15 Meet with the Executive Director followed by Private guided tour of DIA (Detroit Institute for the Arts) The Detroit Institute of Arts has one of the largest and most significant art collections in the United States. With more than 65,000 artworks that date from the earliest civilizations to the present, the museum offers visitors an encounter with human creativity from all over the world. 11:30am -Lunch at the DIA in Dining Room B www.dia.org 1pm Bus picks up at DIA to take us to Motown Museum Afternoon 1:30pm Tour of The Motown museum Originally the recording studios and residence of Berry Gordy and Motown Records. Information for visitors to the museum, and profiles of the label's featured artists including Stevie Wonder, The Supremes, Jackson 5, and Four Tops. Located in Detroit, Michigan, US www.Motownmuseum.org Take bus back to hotel for freshen up 4:30pm Promptly Bus picks up from hotel to take us to Bay View Yacht Club for Private yacht & dinner trip down Detroit river to view the beautifully renovated River park. -

President's Daily Diary Collection (Box 82) at the Gerald R

Scanned from the President's Daily Diary Collection (Box 82) at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE WHITE HOUSE THE DAILY DIARY OF PRESIDENT GERALD R. FORD PLACE DAY BEGAN DATE (Mo., Day, Yr.) HOLIDAY INN MAY 15, 1976 FLINT, MICHIGAN TIME DAY 7:28 a.m. SATURADAY r--PHONE TIME ~ ]: ~~ ACTIVITY Q:; '" I--'-n--'---O-ut--I £ ~ The President was an overnight guest at the Holiday Inn, 2207 W. Bristol Road,F1int, Michigan. Note: The President was accompanied by members of the press throughout his visit to Michigan. 7:28 The President went to the Banquet Room. 7:30 8:10 The President participated in a breafast interview with executives of Booth Newspapers of Michigan. For a list of attendees, see APPENDIX "A.II 8:10 The President returned to his suite. Enroute, he greeted a delegation from the Fraternal Order of Police (FOP). The FOP was holding a statewide memorial service in Flint, Michigan in honor of Michigan police who have lost their lives in the line of duty. For a list of attendees, see APPENDIX "B." 8:21 8:41 P The President talked with David Rood, Editor of the Escanaba Daily Press, Escanaba, Michigan. The President's conver sation was amplified to approximately 35 guests attending the Associated Press Upper Peninsula Editor's Breakfast at the Ramada Inn in Marquette, Michigan. 8:42? The President went to the Hotel Conference Room. 8:45 8:55 The President participated in an interview with Wes Sarginson, anchorman for WWJ-Tv, National Broadcasting Company (NBC) news, Detroit, Michigan. -

Social Media: the Good, the Bad, and the Legalities

Social Media: The Good, The Bad, and the Legalities Speakers: • Matt Bach, Director of Communications, Michigan Municipal League • Steve Baker, Mayor Pro Tem, Berkley • Steven Mann, Principal, Miller Canfield Session Summary ➢Matt Bach – Social media overview and tips ➢Steve Baker – Personal experiences from the trenches ➢Steven Mann – Legal issues surrounding social media Social Media Overview & Tips by Matt Bach Speakers: Questions for you: ➢ Who here is on Facebook? ➢ Your community on Facebook? ➢ What about Twitter? ➢ LinkedIn? Google+? ➢ Instagram? Flickr? ➢ Other? About Me ➢ 25+ years media experience: ➢ 18 years as a journalist at newspapers Greenville, Howell and Flint (also spent time in Grand Rapids, Alpena and Cass City) ➢ Nearly a decade in public relations, media relations, communications – Flint CVB, MML ➢ Director at the League for 8 years ➢ Focusing on Media Relations and Communications ➢ Increase footprint of the League and League members My Social Media Experience The Power of Social Media MML Uses of Social Media Our Facebook, We use it to Twitter and promote our other social programs, such media sites feed as CEAs online our webpage. voting component. Social Media: Fun Facts – Part 1 ➢ Facebook adds 500,00 new users EVERY DAY! ➢ 50% of world population is under age 30 ➢ Today’s college students have never licked a stamp ➢ 53% of millennials would rather lose their sense of smell than their technology ➢ 93% of all buying decisions are influenced by social media Social Media: Fun Facts – Part 2 ➢ By population, Facebook would be the largest country in the world ➢ What is the name of Twitter’s bird logo? ➢ Optimal times people use Facebook: - 3 p.m. -

Press Guests at State Dinners - Candidates for Invitation (1)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 22, folder “Press Guests at State Dinners - Candidates for Invitation (1)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Ron Nessen donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Some items in this folder were not digitized because it contains copyrighted materials. Please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library for access to these materials. Digitized from Box 22 of The Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library PRESS INVITED TO SOCIAL FUNCTIONS Newspaper - News Service_ Executives Washington Post Editor Washington Post Publisher . Washington Star Publisher New Yerk Times Publisher Los .Angeles Tirr es Publisher Cleveland Plain Dealer President Cincinnati Enquirer President Florida Tines Union President Contra Costa caLif _ Publisher c. ~ ;J_. ~~~~ r; u~ Knight-Ridder Newspapers President Copley Newspapers Chairman of the Board Panax Corporation President Gannett Newspapers Publisher Editors Copy Syndicate Publisher Hearst Newspapers Editor-in - Chief Time Inc. Chairman of the Board National Newspaper Pub. President Asso - San Fran Spidel Newspapers-Nevada President Network Execus CBS Chairman of the Board NBC Chairman and Chief Executive Officer ABC President (invited and regretted, invited again) / • POSSIBLE !NV ITA TIONS TO STATE DINNERS Regulars who haven't been: Other Press: Sandy Socolow pb;J iikaeecoff p IE! - "' _.