Large Sex Differences in Chicken Behavior and Brain Gene Expression Coincide with Few Differences in Promoter DNA-Methylation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mice Carrying a Human GLUD2 Gene Recapitulate Aspects of Human Transcriptome and Metabolome Development

Mice carrying a human GLUD2 gene recapitulate aspects of human transcriptome and metabolome development Qian Lia,b,1, Song Guoa,1, Xi Jianga, Jaroslaw Brykc,2, Ronald Naumannd, Wolfgang Enardc,3, Masaru Tomitae, Masahiro Sugimotoe, Philipp Khaitovicha,c,f,4, and Svante Pääboc,4 aChinese Academy of Sciences Key Laboratory of Computational Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences-Max Planck Partner Institute for Computational Biology, Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 200031 Shanghai, China; bUniversity of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 100049 Beijing, China; cMax Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, 04103 Leipzig, Germany; dMax Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics, D-01307 Dresden, Germany; eInstitute for Advanced Biosciences, Keio University, 997-0035 Tsuruoka, Yamagata, Japan; and fSkolkovo Institute for Science and Technology, 143025 Skolkovo, Russia Edited by Joshua M. Akey, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, and accepted by the Editorial Board April 1, 2016 (received for review September 28, 2015) Whereas all mammals have one glutamate dehydrogenase gene metabolic flux from glucose and glutamine to lipids by way of the (GLUD1), humans and apes carry an additional gene (GLUD2), TCA cycle (12). which encodes an enzyme with distinct biochemical properties. To investigate the physiological role the GLUD2 gene may We inserted a bacterial artificial chromosome containing the human play in human and ape brains, we generated mice transgenic for GLUD2. GLUD2 gene into mice and analyzed the resulting changes in the a genomic region containing human We compared effects transcriptome and metabolome during postnatal brain development. on gene expression and metabolism during postnatal development Effects were most pronounced early postnatally, and predominantly of the frontal cortex of the brain in these mice and their wild-type genes involved in neuronal development were affected. -

Identification of Transcriptomic Differences Between Lower

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Identification of Transcriptomic Differences between Lower Extremities Arterial Disease, Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm and Chronic Venous Disease in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells Specimens Daniel P. Zalewski 1,*,† , Karol P. Ruszel 2,†, Andrzej St˛epniewski 3, Dariusz Gałkowski 4, Jacek Bogucki 5 , Przemysław Kołodziej 6 , Jolanta Szyma ´nska 7 , Bartosz J. Płachno 8 , Tomasz Zubilewicz 9 , Marcin Feldo 9,‡ , Janusz Kocki 2,‡ and Anna Bogucka-Kocka 1,‡ 1 Chair and Department of Biology and Genetics, Medical University of Lublin, 4a Chod´zkiSt., 20-093 Lublin, Poland; [email protected] 2 Chair of Medical Genetics, Department of Clinical Genetics, Medical University of Lublin, 11 Radziwiłłowska St., 20-080 Lublin, Poland; [email protected] (K.P.R.); [email protected] (J.K.) 3 Ecotech Complex Analytical and Programme Centre for Advanced Environmentally Friendly Technologies, University of Marie Curie-Skłodowska, 39 Gł˛ebokaSt., 20-612 Lublin, Poland; [email protected] 4 Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Rutgers-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, One Robert Wood Johnson Place, New Brunswick, NJ 08903-0019, USA; [email protected] 5 Chair and Department of Organic Chemistry, Medical University of Lublin, 4a Chod´zkiSt., Citation: Zalewski, D.P.; Ruszel, K.P.; 20-093 Lublin, Poland; [email protected] St˛epniewski,A.; Gałkowski, D.; 6 Laboratory of Diagnostic Parasitology, Chair and Department of Biology and Genetics, Medical University of Bogucki, J.; Kołodziej, P.; Szyma´nska, Lublin, 4a Chod´zkiSt., 20-093 Lublin, Poland; [email protected] J.; Płachno, B.J.; Zubilewicz, T.; Feldo, 7 Department of Integrated Paediatric Dentistry, Chair of Integrated Dentistry, Medical University of Lublin, M.; et al. -

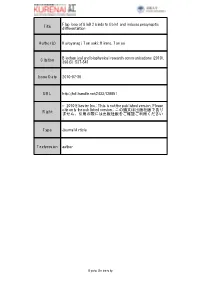

Title Flap Loop of Glud2 Binds to Cbln1 and Induces Presynaptic

Flap loop of GluD2 binds to Cbln1 and induces presynaptic Title differentiation Author(s) Kuroyanagi, Tomoaki; Hirano, Tomoo Biochemical and biophysical research communications (2010), Citation 398(3): 537-541 Issue Date 2010-07-30 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/128851 © 2010 Elsevier Inc.; This is not the published version. Please cite only the published version.; この論文は出版社版であり Right ません。引用の際には出版社版をご確認ご利用ください 。 Type Journal Article Textversion author Kyoto University Flap loop of GluD2 binds to Cbln1 and induces presynaptic differentiation Tomoaki Kuroyanagi and Tomoo Hirano Department of Biophysics, Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan Department of Biophysics, Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan Correspondence should be addressed to: T. Hirano Tel, 81-75-753-4237 Fax, 81-75-753-4227 E-mail, [email protected] (Tomoaki Kuroyanagi); [email protected] (Tomoo Hirano) 1 Abstract Glutamate receptor δ2 (GluD2) is selectively expressed on the postsynaptic spines at parallel-fiber (PF)-Purkinje neuron (PN) synapses. GluD2 knockout mice show a reduced number of PF-PN synapses, suggesting that GluD2 is involved in synapse formation. Recent studies revealed that GluD2 induces presynaptic differentiation in a manner dependent on its N-terminal domain (NTD) through binding of Cbln1 secreted from cerebellar granule neurons. However, the underlying mechanism of the specific binding of the NTD to Cbln1 remains elusive. Here, we have identified the flap loop (Arg321-Trp339) in the NTD of GluD2 (GluD2-NTD) as a crucial region for the binding to Cbln1 and the induction of presynaptic differentiation. -

Multi-Transcriptomic Analysis Points to Early Organelle Dysfunction in 2 Human Astrocytes in Alzheimer’S Disease 3 4 5 Elena Galea1,2,3*, Laura D

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.25.21252422; this version posted March 1, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Multi-transcriptomic analysis points to early organelle dysfunction in 2 human astrocytes in Alzheimer’s disease 3 4 5 Elena Galea1,2,3*, Laura D. Weinstock5, Raquel Larramona1,2,4, Alyssa F. Pybus5, Lydia Giménez- 6 Llort1,6, Carole Escartin7, Levi B. Wood5,8* 7 8 9 1. Institut de Neurociències, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra, 08193 Barcelona, 10 Spain. 11 2. Departament de Bioquímica, Unitat de Bioquímica, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 12 08193 Barcelona, Spain. 13 3. ICREA, 08010 Barcelona, Spain. 14 4. Current address: Celltec-UB, Departament de Biologia Cel.lular, Fisiologia i Immunologia, 15 Universitat de Barcelona, 08028; Institut de Neurociències, Universitat de Barcelona, 08035, 16 Barcelona, Spain. 17 5. Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology, 18 Atlanta, 30332 USA. 19 6. Departament de Psiquiatria i Medicina Forense, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 20 Bellaterra, 08193 Barcelona, Spain. 21 7. Université Paris-Saclay, CEA, CNRS, MIRCen, Laboratoire des Maladies Neurodégénératives, 22 92265, Fontenay-aux-Roses, France. 23 8. George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering and Parker H. Petit Institute for 24 Bioengineering and Bioscience, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, 30332 USA. 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 *Corresponding authors 32 [email protected]; +1 (617) 388 9950 33 [email protected]; +34 935 868 143. -

Nerve Tissue-Specific Human Glutamate Dehydrogenase That Is Thermolabile and Highly Regulated by ADP , I *P

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Chemistry Faculty Publications Chemistry 1997 Nerve tissue-specific umh an glutamate dehydrogenase that is thermolabile and highly regulated by adp / P. Shashidharan, Donald D. Clarke, Naveed Ahmed, Nicholas Moschonas, and Andreas Plaitakis Department of Neurology, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York; Department of Chemistry, Fordham University, Bronx New York, USA; and Department of Biology and School of Health Sciences, University of Crete, Crete, Greece P. Shashidharan Mount Sinai School of Medicine. Department of Neurology, [email protected] Donald Dudley Clarke PhD Fordham University, [email protected] Recommended Citation Shashidharan, P.; Clarke, Donald Dudley PhD; Ahmed, Naveed; and Moschonas, Nicholas, "Nerve tissue-specific umh an glutamate dehydrogenase that is thermolabile and highly regulated by adp / P. Shashidharan, Donald D. Clarke, Naveed Ahmed, Nicholas Moschonas, and Andreas Plaitakis Department of Neurology, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York; Department of Chemistry, Fordham University, Bronx New York, USA; and Department of Biology and School of Health Sciences, University of Crete, Crete, Greece" (1997). Chemistry Faculty Publications. 13. https://fordham.bepress.com/chem_facultypubs/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Chemistry at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chemistry Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Naveed Ahmed Mount Sinai School of Medicine. Department of Neurology Nicholas Moschonas University of Crete. Department of Biology Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/chem_facultypubs Part of the Biochemistry Commons Journal of Neurochemistry Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia © 1997 International Society for Neurochemistry Nerve Tissue-Specific Human Glutamate Dehydrogenase that Is Thermolabile and Highly Regulated by ADP , I *P. -

Maturation, Refinement, and Serotonergic Modulation of Cerebellar Cortical Circuits in Normal Development and in Murine Models of Autism

Hindawi Neural Plasticity Volume 2017, Article ID 6595740, 14 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/6595740 Review Article Maturation, Refinement, and Serotonergic Modulation of Cerebellar Cortical Circuits in Normal Development and in Murine Models of Autism 1,2 3 2 1,2,4 Eriola Hoxha, Pellegrino Lippiello, Bibiana Scelfo, Filippo Tempia, 2 3 Mirella Ghirardi, and Maria Concetta Miniaci 1Neuroscience Institute Cavalieri Ottolenghi (NICO), Torino, Italy 2Department of Neuroscience, University of Torino, Torino, Italy 3Department of Pharmacy, University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy 4National Institute of Neuroscience (INN), Torino, Italy Correspondence should be addressed to Eriola Hoxha; [email protected] Received 28 April 2017; Revised 6 July 2017; Accepted 25 July 2017; Published 15 August 2017 Academic Editor: J. Michael Wyss Copyright © 2017 Eriola Hoxha et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The formation of the complex cerebellar cortical circuits follows different phases, with initial synaptogenesis and subsequent processes of refinement guided by a variety of mechanisms. The regularity of the cellular and synaptic organization of the cerebellar cortex allowed detailed studies of the structural plasticity mechanisms underlying the formation of new synapses and retraction of redundant ones. For the attainment of the monoinnervation of the Purkinje cell by a single climbing fiber, several signals are involved, including electrical activity, contact signals, homosynaptic and heterosynaptic interaction, calcium transients, postsynaptic receptors, and transduction pathways. An important role in this developmental program is played by serotonergic projections that, acting on temporally and spatially regulated postsynaptic receptors, induce and modulate the phases of synaptic formation and maturation. -

Imaging of Camp/PKA Dynamics Induced by Catecholamines in the Neocortical Network Shinobu Nomura

Imaging of cAMP/PKA dynamics induced by catecholamines in the neocortical network Shinobu Nomura To cite this version: Shinobu Nomura. Imaging of cAMP/PKA dynamics induced by catecholamines in the neocortical network. Neurons and Cognition [q-bio.NC]. Université Pierre et Marie Curie - Paris VI, 2014. English. NNT : 2014PA066440. tel-01374733 HAL Id: tel-01374733 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01374733 Submitted on 1 Oct 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Thèse de doctorat de l’Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris 6 Spécialité : Neurosciences Ecole doctorale Cerveau-Cognition-Comportement (ED3C) Présentée par NOMURA Shinobu Pour obtenir le grade de Docteur de l’Université Paris 6 Sujet de la thèse : Imaging of cAMP/PKA dynamics induced by catecholamines in the neocortical network Soutenue le 26 septembre 2014 Devant le jury composé de : Dr Denis Hervé, Président Dr Emmanuel Valjent, Rapporteur Pr Philippe De Deurwaerdère, Rapporteur Dr Régine Hepp, Directeur de thèse Invités exceptionnels Dr Nicolas Gervasi Dr Thierry Gallopin Dr. Bertrand Lambolez 1 Remerciements Je voudrais tout d'abord remercier mon directeur de thèse, Bertrand Lambolez, pour m’avoira ccueilli pour mon stage de M2 puis de m’avoir proposé ce projet sur la transmission catécholaminergique pour poursuivre une thèse à l’UPMC. -

NADPH Homeostasis in Cancer: Functions, Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications

Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy www.nature.com/sigtrans REVIEW ARTICLE OPEN NADPH homeostasis in cancer: functions, mechanisms and therapeutic implications Huai-Qiang Ju 1,2, Jin-Fei Lin1, Tian Tian1, Dan Xie 1 and Rui-Hua Xu 1,2 Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) is an essential electron donor in all organisms, and provides the reducing power for anabolic reactions and redox balance. NADPH homeostasis is regulated by varied signaling pathways and several metabolic enzymes that undergo adaptive alteration in cancer cells. The metabolic reprogramming of NADPH renders cancer cells both highly dependent on this metabolic network for antioxidant capacity and more susceptible to oxidative stress. Modulating the unique NADPH homeostasis of cancer cells might be an effective strategy to eliminate these cells. In this review, we summarize the current existing literatures on NADPH homeostasis, including its biological functions, regulatory mechanisms and the corresponding therapeutic interventions in human cancers, providing insights into therapeutic implications of targeting NADPH metabolism and the associated mechanism for cancer therapy. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy (2020) 5:231; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-020-00326-0 1234567890();,: BACKGROUND for biosynthetic reactions to sustain their rapid growth.5,11 This In cancer cells, the appropriate levels of intracellular reactive realization has prompted molecular studies of NADPH metabolism oxygen species (ROS) are essential for signal transduction and and its exploitation for the development of anticancer agents. cellular processes.1,2 However, the overproduction of ROS can Recent advances have revealed that therapeutic modulation induce cytotoxicity and lead to DNA damage and cell apoptosis.3 based on NADPH metabolism has been widely viewed as a novel To prevent excessive oxidative stress and maintain favorable and effective anticancer strategy. -

Mitochondria Targeting As an Effective Strategy for Cancer Therapy

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Mitochondria Targeting as an Effective Strategy for Cancer Therapy Poorva Ghosh , Chantal Vidal, Sanchareeka Dey and Li Zhang * Department of Biological Sciences, the University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, TX 75080, USA; [email protected] (P.G.); [email protected] (C.V.); [email protected] (S.D.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +972-883-5757 Received: 25 February 2020; Accepted: 6 May 2020; Published: 9 May 2020 Abstract: Mitochondria are well known for their role in ATP production and biosynthesis of macromolecules. Importantly, increasing experimental evidence points to the roles of mitochondrial bioenergetics, dynamics, and signaling in tumorigenesis. Recent studies have shown that many types of cancer cells, including metastatic tumor cells, therapy-resistant tumor cells, and cancer stem cells, are reliant on mitochondrial respiration, and upregulate oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) activity to fuel tumorigenesis. Mitochondrial metabolism is crucial for tumor proliferation, tumor survival, and metastasis. Mitochondrial OXPHOS dependency of cancer has been shown to underlie the development of resistance to chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Furthermore, recent studies have demonstrated that elevated heme synthesis and uptake leads to intensified mitochondrial respiration and ATP generation, thereby promoting tumorigenic functions in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells. Also, lowering heme uptake/synthesis inhibits mitochondrial OXPHOS and effectively reduces oxygen consumption, thereby inhibiting cancer cell proliferation, migration, and tumor growth in NSCLC. Besides metabolic changes, mitochondrial dynamics such as fission and fusion are also altered in cancer cells. These alterations render mitochondria a vulnerable target for cancer therapy. This review summarizes recent advances in the understanding of mitochondrial alterations in cancer cells that contribute to tumorigenesis and the development of drug resistance. -

Succinate Anaplerosis Has an Onco-Driving Potential in Prostate Cancer Cells

cancers Article Succinate Anaplerosis Has an Onco-Driving Potential in Prostate Cancer Cells Ana Carolina B. Sant’Anna-Silva 1,2,*, Juan A. Perez-Valencia 3 , Marco Sciacovelli 4, Claude Lalou 5, Saharnaz Sarlak 5, Laura Tronci 4 , Efterpi Nikitopoulou 4, Andras T. Meszaros 1, Christian Frezza 4, Rodrigue Rossignol 5, Erich Gnaiger 1,2 and Helmut Klocker 6,* 1 Daniel Swarovski Research Laboratory, Department of Visceral, Transplant and Thoracic Surgery, Medical University Innsbruck, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria; [email protected] (A.T.M.); [email protected] (E.G.) 2 Oroboros Instruments GmbH, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria 3 Institute of Human Genetics, Medical University Innsbruck, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria; [email protected] 4 Medical Research Council Cancer Unit, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 0XZ, UK; [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (L.T.); [email protected] (E.N.); [email protected] (C.F.) 5 Institut National de la Santé Et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM) U1211, Bordeaux University, 33076 Bordeaux, France; [email protected] (C.L.); [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (R.R.) 6 Department of Surgery, Division of Experimental Urology, University Hospital for Urology, Medical University Innsbruck, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria * Citation: Sant’Anna-Silva, A.C.B.; Correspondence: [email protected] (A.C.B.S.-S.); [email protected] (H.K.) Perez-Valencia, J.A.; Sciacovelli, M.; Lalou, C.; Sarlak, S.; Tronci, L.; Simple Summary: Depending on the availability of nutrients and increased metabolic demands, Nikitopoulou, E.; Meszaros, A.T.; tumor cells rearrange their metabolism to survive and, ultimately, proliferate. -

Supplementary Text File

Supplemenary information: Functions of prioritised genes Family #1 1. SETDB1: Encodes histone methyl transferase and involved in the regulation of a large neuron specific topological chromatin domain(Jiang et al., 2017)and known to regulate mood related behaviours and NMDA receptor subunit NR2B expression (Jiang et al., 2017) 2. LRP2: is a member of the LDL receptor family, the gene is involved in various neurodevelopmental processes and signalling (Auderset et al., 2016; Fisher and Howie, 2006; Gomes et al., 2016; Spoelgen, 2005; Spuch et al., 2012) 3. TTC21B: Involved in various neurodevelopmental processes (Driver et al., 2017; Stottmann et al., 2009). 4. ADAMTS3: Encodes a member of the ADAMTS (A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs) protein family. Recently the protein is reported to inactivate Reelin (RELN), which is involved in cell positioning and neuronal migration during brain development and modulate NMDA receptor function (Campo et al., 2009; Chen, 2005). A segregating rare variant in RELN is reported in a family with SZ and in an animal model showing behavioral abnormalities related to neuropsychiatric disorders (Sakai et al., 2016; Z. Zhou et al., 2016). 5. LRRTM2: Through the interaction with PSD-95 LRRTM2 regulates surface expression of AMPA receptors and through the LRRTM2 interaction with Neurexin1 the gene also has an important role in excitatory synapse development(de Wit et al., 2009) and maintenance of long-term potentiation (Soler-Llavina et al., 2013). The knockout micealso showed behavioural abnormalities (Voikar et al., 2013). 6. TIAM2: encodes guanine nucleotide exchange factor and is involved in neurite outgrowth, neuronal migration and synapse formation in the cerebral cortex (Goto et al., 2011; Kawauchi et al., 2003). -

Multiple Forms of Glutamate Dehydrogenase in Animals: Structural Determinants and Physiological Implications

biology Review Multiple Forms of Glutamate Dehydrogenase in Animals: Structural Determinants and Physiological Implications Victoria Bunik 1,2,*, Artem Artiukhov 2, Vasily Aleshin 2 and Garik Mkrtchyan 2 1 A.N.Belozersky Institute of Physicochemical Biology, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow 19991, Russia 2 Faculty of Bioengineering and Bioinformatics, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow 19991, Russia; [email protected] (A.A.); [email protected] (V.A.); [email protected] (G.M.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +7-495-939-4484 Academic Editors: Arthur J.L. Cooper and Thomas M. Jeitner Received: 2 October 2016; Accepted: 7 December 2016; Published: 14 December 2016 Abstract: Glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) of animal cells is usually considered to be a mitochondrial enzyme. However, this enzyme has recently been reported to be also present in nucleus, endoplasmic reticulum and lysosomes. These extramitochondrial localizations are associated with moonlighting functions of GDH, which include acting as a serine protease or an ATP-dependent tubulin-binding protein. Here, we review the published data on kinetics and localization of multiple forms of animal GDH taking into account the splice variants, post-translational modifications and GDH isoenzymes, found in humans and apes. The kinetic properties of human GLUD1 and GLUD2 isoenzymes are shown to be similar to those published for GDH1 and GDH2 from bovine brain. Increased functional diversity and specific regulation of GDH isoforms due to alternative splicing and post-translational modifications are also considered. In particular, these structural differences may affect the well-known regulation of GDH by nucleotides which is related to recent identification of thiamine derivatives as novel GDH modulators.