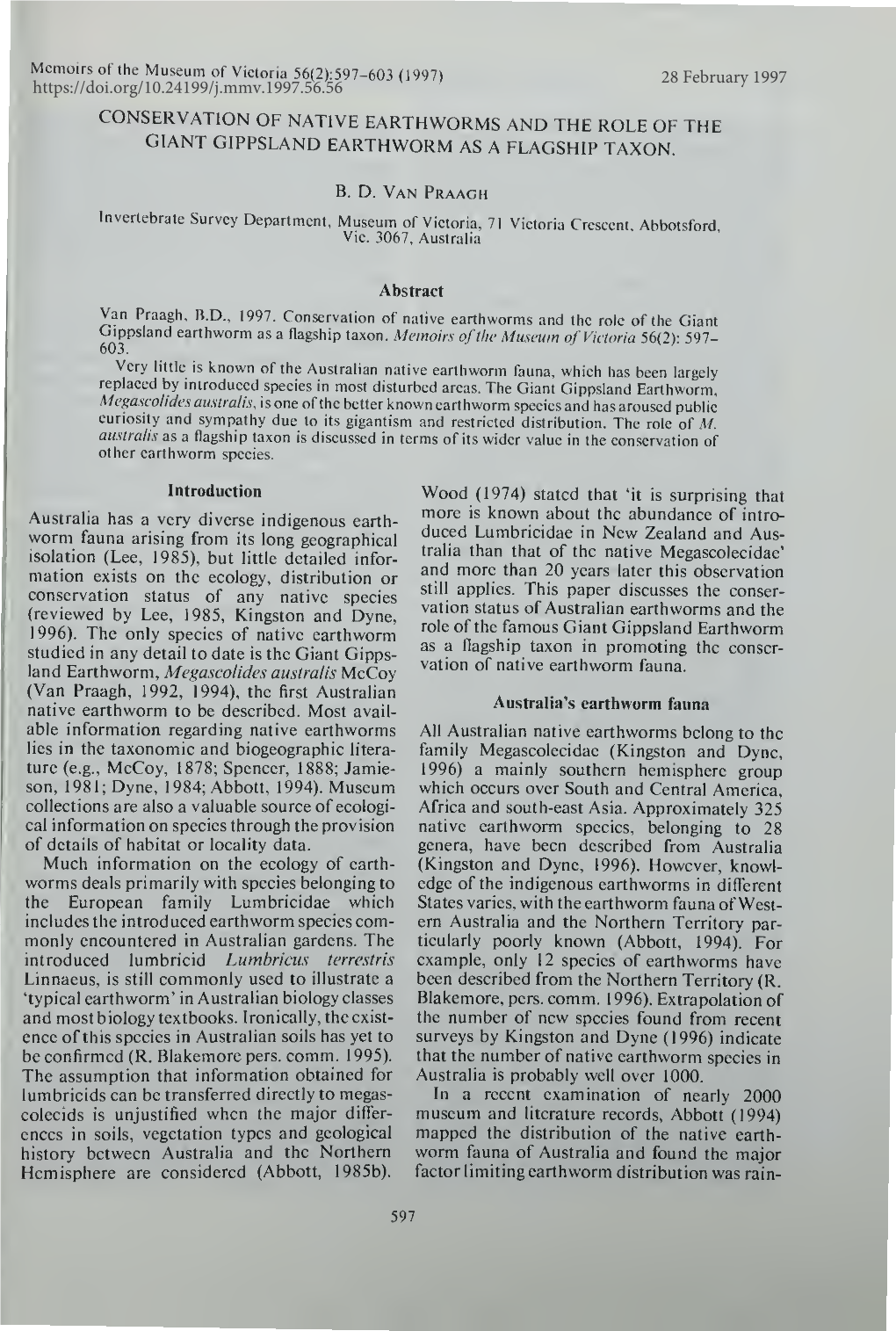

Conservation Ofnative Earthworms and the Role Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DI 136Of2002.Rtf

Australian Capital Territory Nature Conservation Declaration of Protected and Exempt Flora and Fauna 2002 (No. 1) Disallowable instrument DI2002— 136 made under the Nature Conservation Act 1980, s 17 (Declaration of Protected and Exempt Flora and Fauna) I revoke all previous determinations under section 17 of the Nature Conservation Act 1980. I declare the species listed in schedule 1 to be protected fish and protected invertebrates. I declare the species listed in schedule 2 to be exempt animals. I declare the species listed in schedule 3 to be protected native plants. I declare the species listed in schedule 4 to be protected native animals. Dr Maxine Cooper Conservator of Flora and Fauna 28 June 2002 SCHEDULE 1 PROTECTED FISH AND INVERTEBRATES Common Name Scientific Name Clarence River Cod Maccullochella ikei Clarence Galaxias Galaxias johnstoni Swan Galaxias Galaxias fontanus Cairns Birdwing Butterfly Ornithoptera priamnus Mountain Blue Butterfly Papilio ulysses Trout Cod Macullochella maquariensis Murray River Crayfish Eustacus armatus Golden Sun Moth Synemon plana Perunga Grasshopper Perunga ochracea Two-spined Blackfish Gadopsis bisinosus Macquarie Perch Macquaria australasica Canberra Raspy Cricket Cooraboorama canberrae Spiny Freshwater Cray Euastacus crassus Spiny Freshwater Cray Euastacus rieki Spotted Handfish Brachionichthys hirsutus Barred Galaxias Galaxias fuscus Pedder Galaxias Galaxias pedderensis Elizabeth Springs Goby Chlamydogobius micropterus Mary River Cod Maccullochella peelii mariensis Lake Eacham Rainbow Fish Melanotaenia eachamensis Oxleyan Pygmy Perch Nannoperca oxleyana Red-finned Blue-eye Scaturiginichthys vermei1ipinnis Great White Shark Carcharodon carchanias Grey Nurse Shark Carcharias taurus Edgbaston Goby Chiamydogobius squamigenus Murray Hardyhead Craterocephalus fluviatilis Saddled Galaxias Galaxias tanycephalus Dwarf Galaxias Galaxiella pusilla Blind Gudgeon Milyeringa veritas Flinders Ranges Gudgeon Mogurnda n. -

Size Variation and Geographical Distribution of the Luminous Earthworm Pontodrilus Litoralis (Grube, 1855) (Clitellata, Megascolecidae) in Southeast Asia and Japan

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 862: 23–43 (2019) Size variation and distribution of Pontodrilus litoralis 23 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.862.35727 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Size variation and geographical distribution of the luminous earthworm Pontodrilus litoralis (Grube, 1855) (Clitellata, Megascolecidae) in Southeast Asia and Japan Teerapong Seesamut1,2,4, Parin Jirapatrasilp2, Ratmanee Chanabun3, Yuichi Oba4, Somsak Panha2 1 Biological Sciences Program, Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand 2 Ani- mal Systematics Research Unit, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand 3 Program in Animal Science, Faculty of Agriculture Technology, Sakon Nakhon Rajabhat University, Sakon Nakhon 47000, Thailand 4 Department of Environmental Biology, Chubu University, Kasugai 487-8501, Japan Corresponding authors: Somsak Panha ([email protected]), Yuichi Oba ([email protected]) Academic editor: Samuel James | Received 24 April 2019 | Accepted 13 June 2019 | Published 9 July 2019 http://zoobank.org/663444CA-70E2-4533-895A-BF0698461CDF Citation: Seesamut T, Jirapatrasilp P, Chanabun R, Oba Y, Panha S (2019) Size variation and geographical distribution of the luminous earthworm Pontodrilus litoralis (Grube, 1855) (Clitellata, Megascolecidae) in Southeast Asia and Japan. ZooKeys 862: 23–42. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.862.35727 Abstract The luminous earthworm Pontodrilus litoralis (Grube, 1855) occurs in a very wide range of subtropical and tropical coastal areas. Morphometrics on size variation (number of segments, body length and diameter) and genetic analysis using the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (COI) gene sequence were conducted on 14 populations of P. -

Composting Worms for Hawaii

Home Garden Aug. 2005 HG-46 Composting Worms for Hawaii Piper Selden,1 Michael DuPonte,2 Brent Sipes,3 and Kelly Dinges2 1Hawaii Rainbow Worms, 2, 3CTAHR Departments of 2Human Nutrition, Food and Animal Sciences and 3Plant and Environmental Protection Sciences Perionyx excavatus cocoon contains several fertilized eggs, which hatch in 2–3 weeks under suitable conditions. Reproductive rates Blue worm, India blue worm, Malaysian blue vary according to the temperature and environmental worm, traveling worm conditions, which in vermiculture depend on the maintenance of the composting system. Under favorable Origin conditions, blue worms may each produce about 20 offspring per week, which in turn will take 3–5 weeks Perionyx excavatus (Perrier 1872) is found over large to reach sexual maturity. areas of tropical Asia, including India, Malaysia, the Phillippines, and Australia. It is also found in parts of Uses South America, in Puerto Rico, and in some areas of Blue worm is an excellent composting worm and a the United States (south of the Mason Dixon line and prolific breeder given proper nutrient sources and in the Gulf Coast region). Naturalized populations of P. maintenance of its environment, particularly in tropical excavatus have been identified in Hawaii; how long it and subtropical locations. has been here is not known. Description 1 3 Perionyx excavatus is a small earthworm 1 ⁄4–2 ⁄4 inches long. Its front part is deep purple and its hind part is dark red or brown. It has an iridescent, blue-violet sheen on its skin that is visible in bright light. These worms are highly active and twitch when disturbed. -

Phylogenetic and Phenetic Systematics of The

195 PHYLOGENETICAND PHENETICSYSTEMATICS OF THE OPISTHOP0ROUSOLIGOCHAETA (ANNELIDA: CLITELLATA) B.G.M. Janieson Departnent of Zoology University of Queensland Brisbane, Australia 4067 Received September20, L977 ABSTMCT: The nethods of Hennig for deducing phylogeny have been adapted for computer and a phylogran has been constructed together with a stereo- phylogran utilizing principle coordinates, for alL farnilies of opisthopor- ous oligochaetes, that is, the Oligochaeta with the exception of the Lunbriculida and Tubificina. A phenogran based on the sane attributes conpares unfavourably with the phyLogralnsin establishing an acceptable classification., Hennigrs principle that sister-groups be given equal rank has not been followed for every group to avoid elevation of the more plesionorph, basal cLades to inacceptabl.y high ranks, the 0ligochaeta being retained as a Subclass of the class Clitellata. Three orders are recognized: the LumbricuLida and Tubificida, which were not conputed and the affinities of which require further investigation, and the Haplotaxida, computed. The Order Haplotaxida corresponds preciseLy with the Suborder Opisthopora of Michaelsen or the Sectio Diplotesticulata of Yanaguchi. Four suborders of the Haplotaxida are recognized, the Haplotaxina, Alluroidina, Monil.igastrina and Lunbricina. The Haplotaxina and Monili- gastrina retain each a single superfanily and fanily. The Alluroidina contains the superfamiJ.y All"uroidoidea with the fanilies Alluroididae and Syngenodrilidae. The Lurnbricina consists of five superfaniLies. -

The Giant Palouse Earthworm (Driloleirus Americanus)

PETITION TO LIST The Giant Palouse Earthworm (Driloleirus americanus) AS A THREATENED OR ENDANGERED SPECIES UNDER THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT June 30, 2009 Friends of the Clearwater Center for Biological Diversity Palouse Audubon Palouse Prairie Foundation Palouse Group of the Sierra Club 1 June 30, 2009 Ken Salazar, Secretary of the Interior Robyn Thorson, Regional Director U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 1849 C Street N.W. Pacific Region Washington, DC 20240 911 NE 11th Ave Portland, Oregon Dear Secretary Salazar, Friends of the Clearwater, Center for Biological Diversity, Palouse Prairie Foundation, Palouse Audubon, Palouse Group of the Sierra Club and Steve Paulson formally petition to list the Giant Palouse Earthworm (Driloleirus americanus) as a threatened or endangered species pursuant to the Endangered Species Act (”ESA”), 16 U.S.C. §1531 et seq. This petition is filed under 5 U.S.C. 553(e) and 50 CFR 424.14 (1990), which grant interested parties the right to petition for issuance of a rule from the Secretary of Interior. Petitioners also request that critical habitat be designated for the Giant Palouse Earthworm concurrent with the listing, pursuant to 50 CFR 424.12, and pursuant to the Administrative Procedures Act (5 U.S.C. 553). The Giant Palouse Earthworm (D. americanus) is found only in the Columbia River Drainages of eastern Washington and Northern Idaho. Only four positive collections of this species have been made within the last 110 years, despite the fact that the earthworm was historically considered “very abundant” (Smith 1897). The four collections include one between Moscow, Idaho and Pullman, Washington, one near Moscow Mountain, Idaho, one at a prairie remnant called Smoot Hill and a fourth specimen near Ellensberg, Washington (Fender and McKey- Fender, 1990, James 2000, Sánchez de León and Johnson-Maynard, 2008). -

Checklist of New Zealand Earthworms Updated from Lee (1959) by R.J

Checklist of New Zealand Earthworms updated from Lee (1959) by R.J. Blakemore August, 2006 COE fellow, Soil Ecology Group, Yokohama National Univeristy, Japan. Summary This review is based on Blakemore (2004) that updated the work completed over 40 years earlier by Lee (1959) as modified by Blakemore in Lee et al. , (2000) and in Glasby et al. (2007/8) based on the information presented at the "Species 2000" meeting held Jan. 2000 at Te Papa Museum in Wellington, New Zealand. In the current checklist Acanthodrilidae, Octochaetidae and Megascolecidae sensu Blakemore (2000b) are all given separate family status. Whereas Lee (1959) listed approximately 193 species, the current list has about 199 taxa. Because many of the natives have few reports, or are based on only a few specimens, approximately 77 are listed as "threatened" or "endangered" in Dept. Conservation threatened species list (see www.doc.govt.nz/Conservation/001~Plants-and-Animals/006~Threatened-species/Terrestrial-invertebrate-(part-one).asp April, 2005) and three species are detailed in McGuinness (2001). Further studies such as those of Springett & Grey (1998) are required. Currently I seek funding to complete my database into an interactive guide to species, to use to conduct surveys in New Zealand. Some of the changes in Blakemore (2004) from Lee (1959) are: • Microscolex macquariensis (Beddard, 1896) is removed from the list because it is known only from Macquarie Island, which is now claimed as Australian territory (see Blakemore, 2000b). • Megascolides orthostichon (Schmarda, 1861) is removed from the fauna as Fletcher (1886: 524) reported that “on the authority of Captain Hutton” this species was not from New Zealand and may be from Mt Wellington in Tasmania (see Blakemore, 2000b). -

Download Full Article 945.9KB .Pdf File

https://doi.org/10.24199/j.mmv.1972.33.10 7 February 1972 THE AUSTRALIAN EARTHWORM GENUS SPENCER1F.LLA AND DESCRIPTION OF TWO NEW GENERA (Megascolccidae: Oligochaeta) By B. G. M. Jamieson University of Queensland Abstract A neotype is designated for a rediscovered specimen of Diporochaeta notabilis, the only known material of the type-species of SpencerieHa Miehaelsen. The genus appears to belong to a Dichogttster-Megascolides group of genera, though poor preservation precludes certain demonstration of the stomate median meronephridia diagnostic of the group. Specimens from Lord Howe Island are shown to merit recognition of a new genus and species, Paraplutellus insularis, closely allied to Heteroporodrilus Jamieson and Plutellus Perrier on the Australian mainland. The new genus Simsia is established to receive six Victorian species assignable in former classifications to Plutellus, including the new species Simsia longwarricnsis. The type- species S. tuberculoid (Fletcher) is shown to be a senior synonym of Megascolides roseus Spencer. Paraplutellus and Simsia are members of a Perionyx group of genera. Introduction segment V, meronephridia, and tubular prostate glands with unbranched lumen. This superficial The author is currently studying the Baldwin definition (which ignored morphological hetero- Spencer earthworm collection through the kind geneity in other respects) and the disjunct geo- co-operation of Dr B. J. Smith and the authori- graphical distribution, has resulted in a poly- ties of the National Museum of Victoria. Atten- phyletic genus. Revision of the genus and tion has initially been directed to resolving the elucidation of the affinities of the included heterogeneous and clearly polyphyletic assemb- species necessitates examination of the type- lages Plutellus and Diporochaeta into distinct species. -

Threatened Species Protection Act 1995

Contents (1995 - 83) Threatened Species Protection Act 1995 Long Title Part 1 - Preliminary 1. Short title 2. Commencement 3. Interpretation 4. Objectives to be furthered 5. Administration of public authorities 6. Crown to be bound Part 2 - Administration 7. Functions of Secretary 8. Scientific Advisory Committee 9. Community Review Committee Part 3 - Conservation of Threatened Species Division 1 - Threatened species strategy 10. Threatened species strategy 11. Procedure for making strategy 12. Amendment and revocation of strategy Division 2 - Listing of threatened flora and fauna 13. Lists of threatened flora and fauna 14. Notification by Minister and right of appeal 15. Eligibility for listing 16. Nomination for listing 17. Consideration of nomination by SAC 18. Preliminary recommendation by SAC 19. Final recommendation by SAC 20. CRC to be advised of public notification 21. Minister's decision Division 3 - Listing statements 22. Listing statements Division 4 - Critical habitats 23. Determination of critical habitats 24. Amendment and revocation of determinations Division 5 - Recovery plans for threatened species 25. Recovery plans 26. Amendment and revocation of recovery plans Division 6 - Threat abatement plans 27. Threat abatement plans 28. Amendment and revocation of threat abatement plans Division 7 - Land management plans and agreements 29. Land management plans 30. Agreements arising from land management plans 31. Public authority management agreements Part 4 - Interim Protection Orders 32. Power of Minister to make interim protection orders 33. Terms of interim protection orders 34. Notice of order to landholder 35. Recommendation by Resource Planning and Development Commission 36. Notice to comply 37. Notification to other Ministers 38. Limitation of licences, permits, &c., issued under other Acts 39. -

Asian Jumping Worm (Megascolecidae) Impacts on Physical and Biological Characteristics of Turfgrass Ecosystems

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Honors Theses Student Research 2019 Asian Jumping Worm (Megascolecidae) Impacts on Physical and Biological Characteristics of Turfgrass Ecosystems Ella L. Maddi Colby College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/honorstheses Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons, and the Soil Science Commons Colby College theses are protected by copyright. They may be viewed or downloaded from this site for the purposes of research and scholarship. Reproduction or distribution for commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the author. Recommended Citation Maddi, Ella L., "Asian Jumping Worm (Megascolecidae) Impacts on Physical and Biological Characteristics of Turfgrass Ecosystems" (2019). Honors Theses. Paper 965. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/honorstheses/965 This Honors Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. Asian Jumping Worm impacts (Megascolecidae) on Physical and Biological Characteristics of Turfgrass Ecosystems An Honors Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Department of Biology at Colby College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors By Ella Maddi Waterville, ME May 20, 2019 Asian Jumping Worm impacts (Megascolecidae) on Physical and Biological Characteristics of Turfgrass Ecosystems An Honors Thesis presented -

Te Reo O Te Repo – the Voice of the Wetland Introduction 1

TE REO O TE REPO THE VOICE OF THE WETLAND CONNECTIONS, UNDERSTANDINGS AND LEARNINGS FOR THE RESTORATION EDITED BY YVONNE TAURA CHERI VAN SCHRAVENDIJK-GOODMAN OF OUR WETLANDS AND BEVERLEY CLARKSON Te reo o te repo = The voice of the wetland: connections, understandings and learnings for the restoration of our wetlands / edited by Yvonne Taura, Cheri van Schravendijk-Goodman, Beverley Clarkson. -- Hamilton, N.Z. : Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research and Waikato Raupatu River Trust, 2017. 1 online resource ISBN 978-0-478-34799-9 (electronic) ISBN 978-0-947525-03-3 (print) I. Taura, Y., ed. II. Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research New Zealand Ltd. III. Waikato Raupatu River Trust. Published by Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research Private Bag 3127, Hamilton 3216, New Zealand Waikato Raupatu River Trust PO Box 481, Hamilton 3204, New Zealand This handbook was funded mainly by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (contract C09X1002).The handbook is a collaborative project between the Waikato Raupatu River Trust and Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research. Editors: Yvonne Taura (Ngāti Hauā, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngai Te Rangi, Ngāti Rangi, Ngāti Uenuku/Waikato Raupatu River Trust and Manaaki Whenua), Cheri van Schravendijk-Goodman (Te Atihaunui a Papārangi, Ngāti Apa, Ngāti Rangi), and Beverley Clarkson (Manaaki Whenua). Peer reviewers: Anne Austin (Manaaki Whenua), Kiriwai Mangan (Waikato Raupatu Lands Trust), and Monica Peters (people+science). Design and layout: Abby Davidson (NZ Landcare Trust) This work is copyright. The copying, adaptation, or issuing of this work to the public on a non-profit basis is welcomed. No other use of this work is permitted without the prior consent of the copyright holder(s). -

The Wilderness Society

Australia's Faunal Extinction Crisis Senate Inquiry Submission: The Wilderness Society Summary Our magnificent biodiversity and native animals are unique in the world, and have strong cultural and social value to Australians of all backgrounds. Australians depend on thriving ecosystems for their well-being and prosperity, and extinction fundamentally threatens the healthy functioning of those ecosystems. Australia has one of the world’s worst records for extinction and protection of animal species. Australia is ranked first in the world for mammal extinctions, second in the world for ongoing biodiversity loss, and the pace of our extinction crisis is quickening, with the extinction rate likely to double in the next 20 years. Australia has significant international obligations to prevent the extinction of Australia’s animal species. We are also morally, ethically, intergenerationally and practically obliged to end our extinction crisis. However, systemic failures in current Commonwealth environment laws and protections for faunal species ensures we cannot meet those obligations. Under these laws, we have no enforceable mechanisms to end threats to animals and their habitat. Existing protection mechanisms like recovery plans and critical habitat listings are out of date, not implemented and not funded, if they exist at all. The National Reserve System remains important but offers minimal protection where our wildlife is most under threat from human activity. Most worryingly, we have so little data that we do not know the current status and trend of most Australian species, and monitoring of recovery actions is largely non-existent. Australia needs to act quickly to stem the tide of extinction. In the short term, Australia must implement and fully fund existing protection mechanisms and stop threats to wildlife habitat. -

Diplopoda) of Twelve Caves in Western Mecsek, Southwest Hungary

Opusc. Zool. Budapest, 2013, 44(2): 99–106 Millipedes (Diplopoda) of twelve caves in Western Mecsek, Southwest Hungary D. ANGYAL & Z. KORSÓS Dorottya Angyal and Dr. Zoltán Korsós, Department of Zoology, Hungarian Natural History Museum, H-1088 Budapest, Baross u. 13., E-mails: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. Twelve caves of Western Mecsek, Southwest Hungary were examined between September 2010 and April 2013 from the millipede (Diplopoda) faunistical point of view. Ten species were found in eight caves, which consisted eutroglophile and troglobiont elements as well. The cave with the most diverse fauna was the Törökpince Sinkhole, while the two previously also investigated caves, the Abaligeti Cave and the Mánfai-kőlyuk Cave provided less species, which could be related to their advanced touristic and industrial utilization. Keywords. Diplopoda, Mecsek Mts., caves, faunistics INTRODUCTION proved to be rather widespread in the karstic regions of the former Yugoslavia (Mršić 1998, lthough more than 220 caves are known 1994, Ćurčić & Makarov 1998), the species was A from the Mecsek Mts., our knowledge on the not yet found in other Hungarian caves. invertebrate fauna of the caves in the region is rather poor. Only two caves, the Abaligeti Cave All the six millipede species of the Mánfai- and the Mánfai-kőlyuk Cave have previously been kőlyuk Cave (Polyxenus lagurus (Linnaeus, examined in speleozoological studies which in- 1758), Glomeris hexasticha Brandt, 1833, Hap- cludeed the investigation of the diplopod fauna as loporatia sp., Polydesmus collaris C. L. Koch, well (Bokor 1924, Verhoeff 1928, Gebhardt 1847, Ommatoiulus sabulosus (Linnaeus, 1758) and Leptoiulus sp.) were found in the entrance 1933a, 1933b, 1934, 1963, 1966, Farkas 1957).