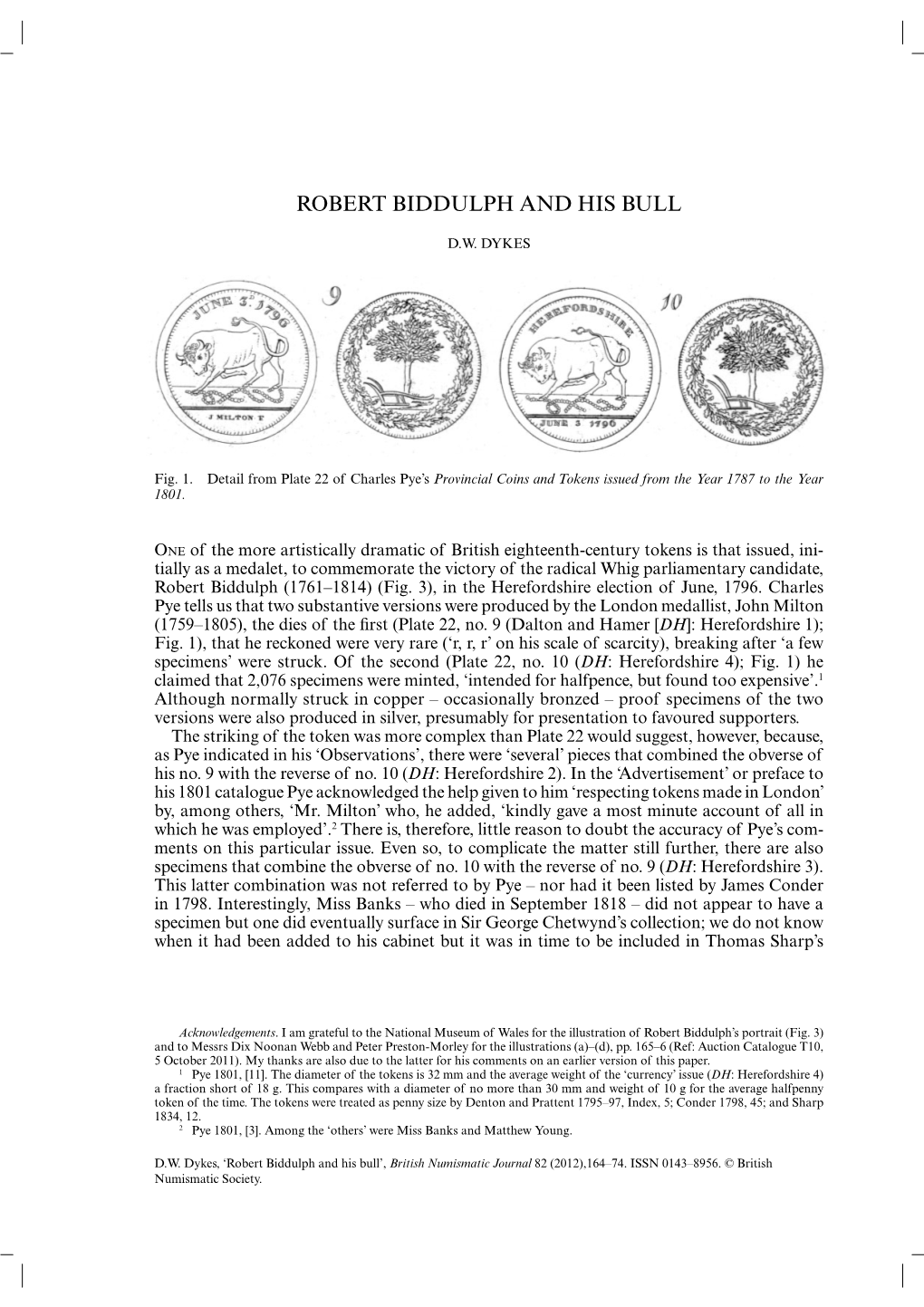

Robert Biddulph and His Bull

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jsomerby's Genealogy Ofthe Arnold Family. from the Somerby Pedigree

JSomerby's Genealogy ofthe Arnold Family. 9 From the Somerby pedigree and his own researches, George C. Arnold, Esq., of Providence, R.1., compiled and drew a genealogical tree of this family, embracing nearly thirty generations, of which a reduced facsimile on a sheet thirty inches long and twenty-four inches wide was executed in 1877 by the Graphic Company, at the expense of himself and Mr.Drowne.* The tree begins with Xnir, king of Gwentland, as does Mr.Somerby's manuscript. We refer our. readers, who wish to trace the family, inlines not given inthese articles', to this tree. Mr. Arnold was able to get on this sheet only a portion of the names he had collected, and he has since add- ed to his genealogical collections. Henry E. M.D., of Newport, R.1., to whom we would return thanks- for assistance, has also spent much time oh this family, and has a valuable collec- tion of materials. —Editor. GENEALOGY OF THE FAMILYOF ARNOLD, 1870. The family of £KtnOltt is ofgreat antiquity, having its origin among the ancient princes of Wales. According to a pedigree recorded inthe College of Arms, they trace from Tnir,King of Gwentland, who flourished about the middle of the twelfth century, and who was paternally descended from Ynir,the second son of Cadwaladr, king of the Britons ; which Cadwaladr built Abergavenny in the county of Monmouth, and its castle, which was afterwards rebuilt by Hamlet ap Hamlet, ap Sir Druce of Balladon, in France, and portions of the walls stillremain. This Ynir,1 Kingof Gwentland, by his wife Nesta, daughter of Jestin -

Herefordshire News Sheet

CONTENTS PROGRAMME JANUARY-OCTOBER 1989 ......................................................................... 2 EDITORIAL ........................................................................................................................... 3 ARS OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE FOR 1989 .................................................................... 3 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING AND DINNER ..................................................................... 4 SURVEY OF NON-CONFORMIST CHAPELS ...................................................................... 5 LUGWARDINE IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY ............................................................... 5 KILPECK ............................................................................................................................... 5 MONMOUTH ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY ...................................................................... 6 FIELD MEETING AT DOCKLOW, 11TH SEPTEMBER, 1988 ................................................ 6 BARN ORCHARD, GREAT CORRAS FARM, KENTCHURCH ............................................. 8 RESULTS OF CORRAS ....................................................................................................... 9 FIELD MEETING AT KENTCHURCH, 9TH OCTOBER, 1988 ................................................ 9 MOATED EARTHWORK IN KENTCHURCH PARISH (Grid Ref 422 270) ............................ 9 PISTLEBROOK FARM (Grid Ref 412 268) ......................................................................... 10 GREAT HOWLE FARM, The Park (SO -

THE SKYDMORES/ SCUDAMORES of ROWLESTONE, HEREFORDSHIRE, Including Their Descendants at KENTCHURCH, LLANCILLO, MAGOR & EWYAS HAROLD

Rowlestone and Kentchurch Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study THE SKYDMORES/ SCUDAMORES OF ROWLESTONE, HEREFORDSHIRE, including their descendants at KENTCHURCH, LLANCILLO, MAGOR & EWYAS HAROLD. edited by Linda Moffatt 2016© from the original work of Warren Skidmore CITATION Please respect the author's contribution and state where you found this information if you quote it. Suggested citation The Skydmores/ Scudamores of Rowlestone, Herefordshire, including their Descendants at Kentchurch, Llancillo, Magor & Ewyas Harold, ed. Linda Moffatt 2016, at the website of the Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com'. DATES • Prior to 1752 the year began on 25 March (Lady Day). In order to avoid confusion, a date which in the modern calendar would be written 2 February 1714 is written 2 February 1713/4 - i.e. the baptism, marriage or burial occurred in the 3 months (January, February and the first 3 weeks of March) of 1713 which 'rolled over' into what in a modern calendar would be 1714. • Civil registration was introduced in England and Wales in 1837 and records were archived quarterly; hence, for example, 'born in 1840Q1' the author here uses to mean that the birth took place in January, February or March of 1840. Where only a baptism date is given for an individual born after 1837, assume the birth was registered in the same quarter. BIRTHS, MARRIAGES AND DEATHS Databases of all known Skidmore and Scudamore bmds can be found at www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com PROBATE A list of all known Skidmore and Scudamore wills - many with full transcription or an abstract of its contents - can be found at www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com in the file Skidmore/Scudamore One-Name Study Probate. -

The Garway Bus Has Been Described As One of the Best Scenic the Garway Hill and Garway Common

D 1 1 0 2 r e b o t c i O a g r k a O d a o r a B 6 m 3 m a t i c m 412 n o o a M p - 412 Garway n The o t 6 3 n n I n o o M y a w r a G e h t t a 2 1 4 e c i v r e S t o s c 412 a l e s d r a n o e W St S t a r t o f W a l k 2 l l i H y a w r a G t r a i d y l l y w g a B 412 F i n i s 6 3 h o 412 f Hill W a l k 2 Pontrilas p o c r O 1 440 k l a W 1 f o k l t 4 X a r p m u T a W t f S o h s i n w o l e m r o W i F . ) 0 4 4 d n a 4 X , 6 3 e h t d n a ( s u b 2 1 4 e h t g n i s u n o d e s a b 412 e r a d n a s e g a l l i v n e e w t e b s k l a w t n i o p o t t n i o p e r a e s e h T . -

Minutes of an Ordinary Meeting Of

Kentchurch Parish Council Minutes of an Ordinary Meeting of Kentchurch Parish Council held at The Auction Rooms, Pontrilas on Wednesday 18th July 2018 No KPC/MW/075 Present Councillor Mr K J (John) Chance Chairman Councillor Mr J L Pring Vice – Chairman Councillor Mrs H Adams Councillor Mr J Cole Councillor Mr T Edwards Clerk Mr M Walker Also Present Ward Councillor Mr Peter Jinman and two further members of the public Meeting declared open by the Chairman at 7.30pm 1.0 Apologies Apologies were received from Mr Dave Roden Lengthsman/Contractor Locality Steward Mr Paul Norris and Police Representative not present The Parish Council resolved to change the order of business at this time to Item 5.1 5.0 Reports 5.1 Ward Councillor Mr Peter Jinman th th Mr Peter Jinman discussed the Sunrise Event for 17 – 19 August 2018 No planning required May need a TENS Licence – Occasional / Premise Licence Meeting to be arranged between organiser and authorised bodies Parish Council to contact Kentchurch Court Estate Trustees Planning Application 1 Hill Cottages – support but must address adequate off road parking Pontrilas Station Working Group Councillor Mr J L Pring Vice – Chairman to be a member (MP, Cabinet and Pontrilas Sawmills are all on board) A465 Speed Limit – waiting for Police to report back Culvert dug up on the Ewyas Harold Road and hedges trimmed *Folly Oaks – campsite – yurts and tents *Rockyfold – caravan *Enforcement Officer to be contacted The Parish Council resumed the correct order of business at this time to Item 2.0 2.0 Declarations -

Gold Medal Ales & Stout

420 KENTCHURCH. Hereford and Abergavenny. The Golden Valley railway was opened for traffic in 188I 1 from Pontrilas to Dorstone; and the extension to Hay, where it joins the Midland line, was completed in 1889. The Pontrilas chemical works are carried on by Captain R. P. Rees, of Abergavenny. Pontr£las Court is the residence of B. St. John Attwood-Mathews, Esq., M.A., J.P. Llanithog was formerly an extra parochial place. PosTAL REGULATIONS. Kentchurch; Elizabeth Kennard, Sub Postm-istress. Letters arrive from Hereford at 9 a.m. ; despatched thereto at 6 p.m. Letters can be registered here. Grosmont is the nearest money order office. Pontrilas is the nearest telegraph office. Post town, Hereford. Post, money order, and telegraph office, Pon trilas ; Samuel Thomas, Sub-Postmaster. Letters arrive at 7.5o a.m. and 1 p.m. ; despatched at 7 p.m. Letters can be registered here. Letters should be addressed, Pontrilas, R.S.O., Herefordshire. Parish Chttrch (St. Mary the Virgin). Rev. Morgan George Watkins, M.A., Rector.; G. Lee Morris, Esq., Churchwarden; Charles Davies, Parish Clerk. National School (boys and girls). Closed at present. Pontrilas Railway Station ( Yunctz"on of the Great Western Railway and Golden Valley Raz7way). William Henry Higginson, Station Master. Pontrilas and Golden Valley Cart Horse Society. Mr. C. W. Wall, Cock yard farm, Abbeydore, Secretary. Pontrzlas and Golden Valley Agricultural Soci'ety.-.Mr. T. F. Morgan, Secretary, Pontrilas Court farm. Assistant Overseer. Mr. Edwin Sayee, Kentchurch. PRIVATE RESIDENTS. Jones, John, hurdle maker, Pontrilas Kennard, Elizabeth, sub-postmistress Attwood-Mathews, Benjamin St. John, King, John, Pontrilas Inn, agent for M.A., J.P., Pontrilas court ARNOLD, PERRETT, & Co.'s Davies, Samuel, Doyer villa Morris, George Lee, Kentchurch court GOLD MEDAL ALES & STOUT, Stewart, W alter, Doyer villa The City Brewery, Hereford. -

HEREFORDSHIRE Is Repeatedly Referred to in Domesday As Lying In

ABO BLOOD GROUPS, HUMAN HISTORY AND LANGUAGE IN HEREFORDSHIRE WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE LOW B FREQUENCY IN EUROPE I. MORGAN WATKIN County Health Department, Aberystwyth Received6.x.64 1.INTRODUCTION HEREFORDSHIREis repeatedly referred to in Domesday as lying in Wales and the county is regularly described as such in the Pipe Rolls until 1249-50. Of the two dozen or so charters granted to the county town, a number are addressed to the citizens of Hereford in Wales. That fluency in Welsh was until 1855oneof the qualifications for the post of clerk to the Hereford city magistrates indicated the county's bilingual nature. The object of the present investigation is to ascertain whether there is any significant genetic difference between the part of Herefordshire conquered by the Anglo-Saxons and the area called "Welsh Hereford- shire ".Assome moorland parishes have lost 50 per cent. of their inhabitants during the last 50 years, the need to carry out the survey is the more pressing. 2.THE HUMAN HISTORY OF HEREFORDSHIRE Pre-Norman Conquest Offa'sgeneral line of demarcation between England and Wales in the eighth century extending in Herefordshire from near Lyonshall to Bridge Sollars, about five miles upstream from Hereford, is inter- mittent in the well-wooded lowlands, being only found in the Saxon clearings. From this Fox (i) infers that the intervening forest with its dense thickets of thorn and bramble filling the space under the tree canopy was an impassable barrier. Downstream to Redbrook (Glos.) the river was probably the boundary but the ferry crossing from Beachley to Aust and the tidal navigational rights up the Wye were retained by the Welsh—facts which suggest that the Dyke was in the nature of an agreed frontier. -

Abbeydore and Bacton, Ewyas Harold Group and Kentchurch Regulation

Latham, James From: Turner, Andrew Sent: 20 July 2017 11:12 To: Neighbourhood Planning Team Subject: RE: Abbeydore & Bacton Group, Ewyas Harold Group and Kentchurch Regulation 16 Neighbourhood Development Plan Consultation RE: Abbeydore & Bacton Group, Ewyas Harold Group and Kentchurch Regulation 16 Neighbourhood Development Plan Consultation Dear Neighbourhood Planning Team, I refer to the above and would make the following comments with regard to the above proposed development plan. It is my understanding that you do not require comment on Core Strategy proposals as part of this consultation or comment on sites which are awaiting or have already been granted planning approval. • Given that no other specific sites have been identified in the plan I am unable to provide comment with regard to potential contamination. Kind regards Andrew Andrew Turner Technical Officer (Air, Land and Water Protection), Environmental Health & Trading Standards, Economy, Communities and Corporate Directorate Herefordshire Council, 8 St Owen Street, Hereford. HR1 2PJ. Direct Tel: 01432 260159 email: [email protected] From: Neighbourhood Planning Team Sent: 27 June 2017 10:30 Subject: Abbeydore & Bacton Group, Ewyas Harold Group and Kentchurch Regulation 16 Neighbourhood Development Plan Consultation Dear Consultee, Abbeydore & Bacton Group, Ewyas Harold Group and Kentchurch Parish Councils have submitted their Regulation 16 Neighbourhood Development Plan (NDP) to Herefordshire Council for consultation. The plan can be viewed at the following link: https://myaccount.herefordshire.gov.uk/abbeydore‐and‐bacton‐ ewyas‐harold‐group‐and‐kentchurch Once adopted, this NDP will become a Statutory Development Plan Document the same as the Core Strategy. The consultation runs from 27 June 2017 to 8 August 2017. -

Contracts Register 2021 (Pdf)

Contract ID Reference Number Directorate (T) Division (T) Contract Title Brief Description Supplier (T) Supplier Address Line 1 Supplier Address Line 2 Supplier Address Line 3 Supplier Address Line 4 Supplier Address Line 5 Supplier Address Line 6 Postcode Company Registration No Charity No Small/Medium Enterprise Supplier Status Start Date End Date Review Date Estimated Annual Value Estimated Contract Value VAT non recoverable Option to Extend Tender Process Contract Type (T) Funding Source (T) Register Comments (Published) 000017 n/a Economy and Place Transport & Access Services AutoCAD based Accident Analysis Software Licence Road Traffic Accident database and analysis software Keysoft Solutions Ltd Ardencroft Court Ardens Grafton ALCESTER WARWICKSHIRE B49 6DP 3472486 Yes Private Limited Company 18/12/2014 17/12/2022 14/06/2022 3,255.00 11,454.00 N/A Yes Quotation Services Council funded 000026 n/a Corporate Services Benefits & Exchequer Academy agreement 858 Revenues and benefits system 858 Capita Business Services Ltd PO Box 212 Faverdale Industrial Estate DARLINGTON DL1 9HN No Private Limited Company 28/05/2004 31/03/2024 27/09/2023 85,000.00 1,020,000.00 N/A Yes Tender Services Council funded 000027 n/a Corporate Services Benefits & Exchequer Remote Support Service for Academy agreement Maintenance for the Revenues and Benefits system Capita Business Services Ltd PO Box 212 Faverdale Industrial Estate DARLINGTON DL1 9HN No Private Limited Company 01/03/2011 31/03/2024 27/09/2023 98,000.00 868,000.00 N/A Yes Tender Services Council -

The Orchard, Kentchurch, Pontrilas, Herefordshire HR2

The Orchard, Kentchurch, Pontrilas, Herefordshire HR2 0BJ Description with inset stainless steel sink unit, plumbing for washing machine, fitted wall and base cupboards, A very well presented, relatively modern detached double glazed door to rear gardens. bungalow in a superb rural location in south Inner Hallway Herefordshire. The accommodation has been very well maintained and is in a first class state of repair With cloaks cupboard having hanging rails, lighting and decoration throughout. and shelving. Airing cupboard with lagged tank, wood slat shelving and immersion heater. Further The property occupies a superb elevated location in storage cupboard. rural countryside with far reaching views to The Master Bedroom 3.98m x 3.57m (13’1” x 11’9”) The Orchard, Skirrid, Sugarloaf and the Black Mountains. With views to the south and west. Kentchurch, Easy access is provided to an excellent range of En Suite Shower Room Pontrilas, local amenities including; school, church, public house, doctor’s surgery, service station, community With fully tiled shower cubicle, vanity unit and WC Herefordshire. hall and a range of shops, Hereford City being some low level flush suite. HR2 0BJ 13 miles north and Abergavenny some 13 miles Bedroom 2 3.574m x 2.77m (11’9” x 9’1”) south with the links to national motorway network at Plus a large walk-in bay. Monmouth some 12 miles to the east. Bedroom 3 2.97m x 2.69m (9’9” x 8’10”) Summary of features Accommodation Bedroom 4/Office 3.18m x 2.69m (10’5” x 8’10”) Superb location within the village of The accommodation has the benefit of double An L shaped room. -

Early Chancery Proceedings, Series

SCUDAMORE/SKYDMORE IN EARLY CHANCERY AND OTHER LEGAL PROCEEDINGS. by Warren Skidmore [I have printed herewith extracts made at the Public Record Office in London over a period of several summers from the early court records. The indexes to these are several and varied, and these notes suffer from their inadequacies. For some there is only an index to plaintiffs, and for others only an index to the surname of the first plaintiff and the first defendant. Thus a case of Smith vs. Jones, Skydmore, Skydmore, and Skydmore (which would be likely to give a substantial pedigree) would be indexed only under Smith and Jones. The handwriting can be dreadful, and the condition of many of the parchments (which were rained on in the Tower of London for centuries) even worse. Never the less John Hunt and I plowed through hundreds of them down to 1714, and the frequent exciting discoveries kept us at a sometimes tedious chore. The quarrels in chancery probably rank next after probates as a source of information on families relationships. I have added in parentheses (with an asterisk*) my own page numbers, which usually has more information than will be found in the brief abstracts fed into the computer here. John Hunt has a complete file as well, handled differently. Much of the data copied in London has also found its way into the proper place in Thirty Generations, and will be found elsewhere on this CD. It will be seen that I have copied indexes (even AFTER 1714 not found here), but have barely touched the original files of a good many of the later series. -

Pontrilas Court Pontrilas | Herefordshire | HR2 0EH Pontrilas Court

Pontrilas Court Pontrilas | Herefordshire | HR2 0EH Pontrilas Court One of the great Grade II* Listed houses on the Herefordshire/Monmouthshire border in a delightful location equidistant to Abergavenny, Hereford and Monmouth. Pontrilas was for many generations the seat of the branch of the great Herefordshire family, Baskerville of Eardisley. The Court is stated as having been built between 1630 and 1640 for Walter Baskerville, though the first Baskerville known to have lived at Pontrilas was Thomas Baskerville who died in 1551. When King James I visited Hereford, a Baskerville rode to meet him escorted by 23 sons of his ‘own getting’, well-mounted and well-armed. Despite their remarkable early fertility, the male line of the Baskervilles from Pontrilas seemed to have died out by the end of the 17th century. Pontrilas then came into the possession of Sir Philip Jackson, a merchant who died about 1734, and in the latter part of the century Pontrilas passed to Henry Shiffner, and in 1840 to Colonel John Scudamore from Kentchurch Court whose family sold the house a century later. For many years George Bentham, the Botanist (1800-1844), a vital force in the creation of Kew Gardens, lived at Pontrilas and it was thought that he was responsible for planting many of the specimen trees on the property and the surrounding area. The current owners have continued the improvements commenced by their predecessors. • Great hall, drawing room, dining room, library • 6 main bedrooms, 6 bath/shower rooms • Second floor offices/suite • 3 bedroom cottage • Coach house, garaging and flat • Tennis court, swimming pool and modern pool house • Mature gardens and grounds • Fishing rights • In all about 12 acres STEP INSIDE Pontrilas Court has been the site of an important manor house for much of the last millennium though the present house dates back to the mid-17th century with later additions during the 18th and 19th centuries.