Ch. 55 Conservation Ecology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.CONSERVATION GENETICS. APPLYING EVOLUTIONARY

Mètode Science Studies Journal ISSN: 2174-3487 [email protected] Universitat de València España Caballero Rúa, Armando CONSERVATION GENETICS. APPLYING EVOLUTIONARY CONCEPTS TO THE CONSERVATION OF BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY Mètode Science Studies Journal, núm. 4, 2014, pp. 73-77 Universitat de València Valencia, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=511751359009 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative MONOGRAPH MÈTODE Science Studies Journal, 4 (2014): 73-77. University of Valencia. DOI: 10.7203/metode.78.2452 ISSN: 2174-3487. Article received: 01/03/2013, accepted: 02/05/2013. CONSERVATION GENETICS APPLYING EVOLUTIONARY CONCEPTS TO THE CONSERVATION OF BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY ARMANDO CABALLERO RÚA Greater understanding of the forces driving evolutionary change and infl uencing populations, together with the latest genetic analysis techniques, have helped conserve of biodiversity for the last twenty years. This new application of genetics is called conservation genetics. Keywords: genetic drift, inbreeding, extinction vortex, effective population size. One of the most pressing problems caused by human 2012) are the pillars supporting conservation genetics. population growth and the irresponsible use of The launch in 2000 of the journal Conservation natural resources is the conservation of biodiversity. Genetics, dealing specifi cally with this fi eld, and Species are disappearing at a breakneck pace and a more recently, in 2009, of the journal Conservation growing number of them require human intervention Genetics Resources highlight the importance of to optimize their management and ensure their this new application of population and evolutionary survival. -

Effective Population Size and Genetic Conservation Criteria for Bull Trout

North American Journal of Fisheries Management 21:756±764, 2001 q Copyright by the American Fisheries Society 2001 Effective Population Size and Genetic Conservation Criteria for Bull Trout B. E. RIEMAN* U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, 316 East Myrtle, Boise, Idaho 83702, USA F. W. A LLENDORF Division of Biological Sciences, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana 59812, USA Abstract.ÐEffective population size (Ne) is an important concept in the management of threatened species like bull trout Salvelinus con¯uentus. General guidelines suggest that effective population sizes of 50 or 500 are essential to minimize inbreeding effects or maintain adaptive genetic variation, respectively. Although Ne strongly depends on census population size, it also depends on demographic and life history characteristics that complicate any estimates. This is an especially dif®cult problem for species like bull trout, which have overlapping generations; biologists may monitor annual population number but lack more detailed information on demographic population structure or life history. We used a generalized, age-structured simulation model to relate Ne to adult numbers under a range of life histories and other conditions characteristic of bull trout populations. Effective population size varied strongly with the effects of the demographic and environmental variation included in our simulations. Our most realistic estimates of Ne were between about 0.5 and 1.0 times the mean number of adults spawning annually. We conclude that cautious long-term management goals for bull trout populations should include an average of at least 1,000 adults spawning each year. Where local populations are too small, managers should seek to conserve a collection of interconnected populations that is at least large enough in total to meet this minimum. -

Genetic and Demographic Dynamics of Small Populations of Silene Latifolia

Heredity (2003) 90, 181–186 & 2003 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0018-067X/03 $25.00 www.nature.com/hdy Genetic and demographic dynamics of small populations of Silene latifolia CM Richards, SN Emery and DE McCauley Department of Biological Sciences, Vanderbilt University, PO Box 1812, Station B, Nashville, TN 37235, USA Small local populations of Silene alba, a short-lived herbac- populations doubled in size between samples, while others eous plant, were sampled in 1994 and again in 1999. shrank by more than 75%. Similarly, expected heterozygosity Sampling included estimates of population size and genetic and allele number increased by more than two-fold in diversity, as measured at six polymorphic allozyme loci. individual populations and decreased by more than three- When averaged across populations, there was very little fold in others. When population-specific change in number change between samples (about three generations) in and change in measures of genetic diversity were considered population size, measures of within-population genetic together, significant positive correlations were found be- diversity such as number of alleles or expected hetero- tween the demographic and genetic variables. It is specu- zygosity, or in the apportionment of genetic diversity within lated that some populations were released from the and among populations as measured by Fst. However, demographic consequences of inbreeding depression by individual populations changed considerably, both in terms gene flow. of numbers of individuals and genetic composition. Some Heredity (2003) 90, 181–186. doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800214 Keywords: genetic diversity; demography; inbreeding depression; gene flow Introduction 1986; Lynch et al, 1995), the interaction of genetics and demography could also influence population persistence How genetics and demography interact to influence in common species, because it is generally accepted that population viability has been a long-standing question in even many abundant species are not uniformly distrib- conservation biology. -

Conservation Biology and Global Change

honeyeater (Melipotes carolae), a species that had never been described before (Figure 56.1). In 2005, a team of American, Indonesian, and Australian biologists experienced many mo- 56 ments like this as they spent a month cataloging the living riches hidden in a remote mountain range in Indonesia. In addition to the honeyeater, they discovered dozens of new frog, butterfly, and plant species, including five new palms. Conservation To date, scientists have described and formally named about 1.8 million species of organisms. Some biologists think Biology and that about 10 million more species currently exist; others es- timate the number to be as high as 100 million. Some of the Global Change greatest concentrations of species are found in the tropics. Unfortunately, tropical forests are being cleared at an alarm- ing rate to make room for and support a burgeoning human population. Rates of deforestation in Indonesia are among the highest in the world (Figure 56.2). What will become of the smoky honeyeater and other newly discovered species in Indonesia if such deforestation continues unchecked? Throughout the biosphere, human activities are altering trophic structures, energy flow, chemical cycling, and natural disturbance—ecosystem processes on which we and all other species depend (see Chapter 55). We have physically altered nearly half of Earth’s land surface, and we use over half of all accessible surface fresh water. In the oceans, stocks of most major fisheries are shrinking because of overharvesting. By some estimates, we may be pushing more species toward ex- tinction than the large asteroid that triggered the mass ex- tinctions at the close of the Cretaceous period 65.5 million years ago (see Figure 25.16). -

Conservation Genetics – Science in the Service of Nature

#0# Acta Biologica 27/2020 | www.wnus.edu.pl/ab | DOI: 10.18276/ab.2020.27-12 | strony 131–141 Conservation genetics – science in the service of nature Cansel Taşkın,1 Jakub Skorupski2 1 Department of Biology, Ankara University, 06930 Ankara, Turkey, ORCID: 0000-0001-6899-701X 2 Institute of Marine and Environmental Sciences, University of Szczecin, Adama Mickiewicza 16 St., 70-383 Szczecin; Polish Society for Conservation Genetics LUTREOLA, Maciejkowa 21 St., 70-374 Szczecin, Poland Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] Keywords ecogenomics, extinction risk, extinction vortex, genetic load, genomics, inbreeding depression, management units Abstract Conservation genetics is a subdicipline of conservation biology which deals with the extinction risk and many other problems of nature conservation by using genetic tools and techniques. Conservation genetics is a very good example of the practical use of scientific achievements in nature protection. Although its name seems to be self-defining, its specific area of interest, conceptual apparatus and methodological workshop are not widely known and recognizable. The purpose of this review is to clarify any ambiguities and inconsistencies in this respect. It explore what is conservation genetics, what research and practical issues does it deal with and how they can be solved. Genetyka konserwatorska – nauka w służbie przyrody Słowa kluczowe depresja wsobna, ekogenomika, genomika, jednostki zarządzania, obciążenie genetyczne, ryzyko wyginięcia, wir wymierania Streszczenie Genetyka konserwatorska jest subdyscypliną biologii konserwatorskiej, która zajmuje się ryzykiem wyginięcia gatunków i wieloma innymi problemami ochrony przyrody, przy użyciu narzędzi i technik genetycznych. Genetyka konserwatorska jest bardzo dobrym przykładem praktycznego wykorzystania osiągnięć nauki w ochronie przyrody. -

Status and Trends of Land Degradation and Restoration and Associated Changes in Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functions

IPBES/6/INF/1/Rev.1 Chapter 4 Status and trends of land degradation and restoration and associated changes in biodiversity and ecosystem functions Coordinating Lead Authors Stephen Prince (United States of America), Graham Von Maltitz (South Africa), Fengchun Zhang (China) Lead Authors Kenneth Byrne (Ireland), Charles Driscoll (United States of America), Gil Eshel (Israel), German Kust (Russian Federation), Cristina Martínez-Garza (Mexico), Jean Paul Metzger (Brazil), Guy Midgley (South Africa), David Moreno Mateos (Spain), Mongi Sghaier (Tunisia/OSS), San Thwin (Myanmar) Fellow Bernard Nuoleyeng Baatuuwie (Ghana) Contributing Authors Albert Bleeker (the Netherlands), Molly E. Brown (United States of America), Leilei Cheng (China), Kirsten Dales (Canada), Evan Andrew Ellicot (United States of America), Geraldo Wilson Fernandes (Brazil), Violette Geissen (the Netherlands), Panu Halme (Finland), Jim Harris (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland), Roberto Cesar Izaurralde (United States of America), Robert Jandl (Austria), Gensuo Jia (China), Guo Li (China), Richard Lindsay (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland), Giuseppe Molinario (United States of America), Mohamed Neffati (Tunisia), Margaret Palmer (United States of America), John Parrotta (United States of America), Gary Pierzynski (United States of America), Tobias Plieninger (Germany), Pascal Podwojewski (France), Bernardo Dourado Ranieri (Brazil), Mahesh Sankaran (India), Robert Scholes (South Africa), Kate Tully (United States of America), Ernesto F. Viglizzo (Argentina), Fei Wang (China), Nengwen Xiao (China), Qing Ying (China), Caiyun Zhao (China) Review Editors Chencho Norbu (Bhutan), Jim Reynolds (United States of America) This chapter should be cited as: Prince, S., Von Maltitz, G., Zhang, F., Byrne, K., Driscoll, C., Eshel, G., Kust, G., Martínez-Garza, C., Metzger, J. -

Ecocide: the Missing Crime Against Peace'

35 690 Initiative paper from Representative Van Raan: 'Ecocide: The missing crime against peace' No. 2 INITIATIVE PAPER 'The rules of our world are laws, and they can be changed. Laws can restrict, or they can enable. What matters is what they serve. Many of the laws in our world serve property - they are based on ownership. But imagine a law that has a higher moral authority… a law that puts people and planet first. Imagine a law that starts from first do no harm, that stops this dangerous game and takes us to a place of safety….' Polly Higgins, 2015 'We need to change the rules.' Greta Thunberg, 2019 Table of contents Summary 1 1. Introduction 3 2. The ineffectiveness of current legislation 7 3. The legal framework for ecocide law 14 4. Case study: West Papua 20 5. Conclusion 25 6. Financial section 26 7. Decision points 26 Appendix: The institutional history of ecocide 29 Summary Despite all our efforts, the future of our natural environments, habitats, and ecosystems does not look promising. Human activity has ensured that climate change continues to persist. Legal instruments are available to combat this unprecedented damage to the natural living environment, but these instruments have proven inadequate. With this paper, the initiator intends to set forth an innovative new legal concept. This paper is a study into the possibilities of turning this unprecedented destruction of our natural environment into a criminal offence. In this regard, we will use the term ecocide, defined as the extensive damage to or destruction of ecosystems through human activity. -

Desertification and Agriculture

BRIEFING Desertification and agriculture SUMMARY Desertification is a land degradation process that occurs in drylands. It affects the land's capacity to supply ecosystem services, such as producing food or hosting biodiversity, to mention the most well-known ones. Its drivers are related to both human activity and the climate, and depend on the specific context. More than 1 billion people in some 100 countries face some level of risk related to the effects of desertification. Climate change can further increase the risk of desertification for those regions of the world that may change into drylands for climatic reasons. Desertification is reversible, but that requires proper indicators to send out alerts about the potential risk of desertification while there is still time and scope for remedial action. However, issues related to the availability and comparability of data across various regions of the world pose big challenges when it comes to measuring and monitoring desertification processes. The United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification and the UN sustainable development goals provide a global framework for assessing desertification. The 2018 World Atlas of Desertification introduced the concept of 'convergence of evidence' to identify areas where multiple pressures cause land change processes relevant to land degradation, of which desertification is a striking example. Desertification involves many environmental and socio-economic aspects. It has many causes and triggers many consequences. A major cause is unsustainable agriculture, a major consequence is the threat to food production. To fully comprehend this two-way relationship requires to understand how agriculture affects land quality, what risks land degradation poses for agricultural production and to what extent a change in agricultural practices can reverse the trend. -

Maturation at a Young Age and Small Size of European Smelt (Osmerus

Arula et al. Helgol Mar Res (2017) 71:7 DOI 10.1186/s10152-017-0487-x Helgoland Marine Research ORIGINAL ARTICLE Open Access Maturation at a young age and small size of European smelt (Osmerus eperlanus): A consequence of population overexploitation or climate change? Timo Arula*, Heli Shpilev, Tiit Raid, Markus Vetemaa and Anu Albert Abstract Age of fsh at maturation depends on the species and environmental factors but, in general, investment in growth is prioritized until the frst sexual maturity, after which a considerable and increasing proportion of resources are used for reproduction. The present study summarizes for the frst the key elements of the maturation of European smelt (Osmerus eperlanus) young of the year (YoY) in the North-eastern Gulf of Riga (the Baltic Sea). Prior to the changes in climatic conditions and collapse of smelt fshery in the 1990s in the Gulf of Riga, smelt attained sexual maturity at the age of 3–4 years. We found a substantial share (22%) of YoY smelt with maturing gonads after the collapse of the smelt fsheries. Maturing individuals had a signifcantly higher weight, length and condition factor than immature YOY, indicating the importance of individual growth rates in the maturation process. The proportion of maturing YoY individuals increased with fsh size. We discuss the factors behind prioritizing reproduction overgrowth in early life and its implications for the smelt population dynamics. Keywords: Osmerus eperlanus, Early maturation, Young of the year (0 ), Commercial fsheries + Background and younger ages [5–8]. Such shifts time of maturation Age of fsh at maturation depends on the species and might have drastic consequences for fsh population environmental factors but, in general, investment in dynamics, as the share of early maturing individuals will growth is prioritized until the frst sexual maturity, increase in population [9]. -

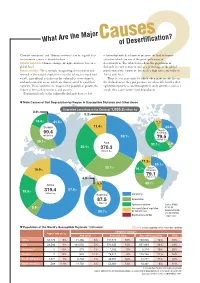

What Are the Major Causes of Desertification?

What Are the Major Causesof Desertification? ‘Climatic variations’ and ‘Human activities’ can be regarded as relationship with development pressure on land by human the two main causes of desertification. activities which are one of the principal causes of Climatic variations: Climate change, drought, moisture loss on a desertification. The table below shows the population in global level drylands by each continent and as a percentage of the global Human activities: These include overgrazing, deforestation and population of the continent. It reveals a high ratio especially in removal of the natural vegetation cover(by taking too much fuel Africa and Asia. wood), agricultural activities in the vulnerable ecosystems of There is a vicious circle by which when many people live in arid and semi-arid areas, which are thus strained beyond their the dryland areas, they put pressure on vulnerable land by their capacity. These activities are triggered by population growth, the agricultural practices and through their daily activities, and as a impact of the market economy, and poverty. result, they cause further land degradation. Population levels of the vulnerable drylands have a close 2 ▼ Main Causes of Soil Degradation by Region in Susceptible Drylands and Other Areas Degraded Land Area in the Dryland: 1,035.2 million ha 0.9% 0.3% 18.4% 41.5% 7.7 % Europe 11.4% 34.8% North 99.4 America million ha 32.1% 79.5 million ha 39.1% Asia 52.1% 5.4 26.1% 370.3 % million ha 11.5% 33.1% 30.1% South 16.9% 14.7% America 79.1 million ha 4.8% 5.5 40.7% Africa -

Conservation Biology Conservation Genetics

DOTTORATO IN SCIENZE AMBIENTALI Genetica e conservazione della biodiversità Ettore Randi Laboratorio di Genetica ISPRA, sede di Ozzano Emilia (BO) Università di Bologna [email protected] giovedì 1 ottobre ore 14:30-17:30 1 genetica, genomica e conservazione della biodiversità 2 conseguenze genetiche della frammentazione venerdì 2 ottobre ore 14:30-17:30 3 ibridazione naturale e antropogenica 4 monitoraggio genetico delle popolazioni naturali Corso di Dottorato in Scienze Ambientali – Università degli Studi di Milano Coordinatore: Prof. Nicola Saino; [email protected] website: http://www.environsci.unimi.it/ Genetica, genomica e conservazione della biodiversità Ettore Randi Laboratorio di Genetica ISPRA, sede di Ozzano Emilia (BO) [email protected] Images dowloaded for non-profit educational presentation use only Transition from conservation GENETICS to conservation GENOMICS Next-generation (massive parallel) sequencing: … not simply more markers Conservation Biology 1980 1986 Conservation Genetics “Conservation genetics: the theory and practice of genetics in the preservation of species as dynamic entities capable of evolving to cope with environmental change to minimize their risk of extinction” Conservation Genetics/Genomics Genetic diversity is the driver and the consequence of biological evolution protection & conservation of biodiversity protection & conservation of the processes & products of evolution The Convention on Biological Diversity CDB Rio de Janeiro 1992 Biodiversity Biodiversity = the diversity -

An Axiomatic Foundation of the Ecological Footprint

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Kuhn, Thomas; Pestow, Radomir; Zenker, Anja Working Paper An Axiomatic Foundation of the Ecological Footprint Chemnitz Economic Papers, No. 025 Provided in Cooperation with: Chemnitz University of Technology, Faculty of Economics and Business Administration Suggested Citation: Kuhn, Thomas; Pestow, Radomir; Zenker, Anja (2018) : An Axiomatic Foundation of the Ecological Footprint, Chemnitz Economic Papers, No. 025, Chemnitz University of Technology, Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, Chemnitz This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/190431 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Faculty of Economics and Business Administration An Axiomatic Foundation of the Ecological Footprint Thomas Kuhn Radomir Pestow Anja Zenker Chemnitz Economic Papers, No.