“CUBANS VOTE CUBAN”: LOCAL POLITICS and LATINO IDENTITY in MIAMI, FLORIDA, 1965 – 1985. Jeanine Navarrete a Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4622 EX R·E N S I 0 N S 0 F REMARKS

4622 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD- HOUSE Mar ch 20 EX r ·E N S I 0 N S 0 F REMARKS Some Solid Facts on Imported Residual Comment. Actually, the real growth in now being used to haul it to markets for dependence on residual in New England, did merly considered immune, and further Fuel Oil not take place until cheap foreign oil be damage to the coal and railroad industries gan to come in in volume in the late 1940's. serving New England is threatened. In 1946, for instance, New England used only 3. The statement is made that the New EXTENSION OF REMARKS 30 m11lion barrels of residual, which pro England area "could never go back to coal, OF vided 24.6 percent of her competitive energy and must have increasing quantities of this requirementS. This was only about 9 mil product (residual) every year as its economy HON. ED EDMONDSON lion barrels more than was used in 1935. expands" (p. 3) . OF OKLAHOMA However, between 1946 and 1960, total re Comment. This statement is completely IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES sidual use increased to 71 million barrels, indefensible. New England could certainly and in that year it provided 31.1 percent of return to coal as a major fuel source, and Tuesday, March 20, 1962 her competitive energy. Coal, in the mean we are convinced that it eventually will have Mr. EDMONDSON. Mr. Speaker, it time, dropped from 54.7 percent of New Eng to do so. This switch could be made with is difficult to look objectively at any land's energy source in 1946 to 17.7 percent little impact on fuel costs, and it would in 1960. -

Wilderness on the Edge: a History of Everglades National Park

Wilderness on the Edge: A History of Everglades National Park Robert W Blythe Chicago, Illinois 2017 Prepared under the National Park Service/Organization of American Historians cooperative agreement Table of Contents List of Figures iii Preface xi Acknowledgements xiii Abbreviations and Acronyms Used in Footnotes xv Chapter 1: The Everglades to the 1920s 1 Chapter 2: Early Conservation Efforts in the Everglades 40 Chapter 3: The Movement for a National Park in the Everglades 62 Chapter 4: The Long and Winding Road to Park Establishment 92 Chapter 5: First a Wildlife Refuge, Then a National Park 131 Chapter 6: Land Acquisition 150 Chapter 7: Developing the Park 176 Chapter 8: The Water Needs of a Wetland Park: From Establishment (1947) to Congress’s Water Guarantee (1970) 213 Chapter 9: Water Issues, 1970 to 1992: The Rise of Environmentalism and the Path to the Restudy of the C&SF Project 237 Chapter 10: Wilderness Values and Wilderness Designations 270 Chapter 11: Park Science 288 Chapter 12: Wildlife, Native Plants, and Endangered Species 309 Chapter 13: Marine Fisheries, Fisheries Management, and Florida Bay 353 Chapter 14: Control of Invasive Species and Native Pests 373 Chapter 15: Wildland Fire 398 Chapter 16: Hurricanes and Storms 416 Chapter 17: Archeological and Historic Resources 430 Chapter 18: Museum Collection and Library 449 Chapter 19: Relationships with Cultural Communities 466 Chapter 20: Interpretive and Educational Programs 492 Chapter 21: Resource and Visitor Protection 526 Chapter 22: Relationships with the Military -

Leadership and Ethical Development: Balancing Light and Shadow

LEADERSHIP AND ETHICAL DEVELOPMENT: BALANCING LIGHT AND SHADOW Benyamin M. Lichtenstein, Beverly A. Smith, and William R. Torbert A&stract: What makes a leader ethical? This paper critically examines the answer given by developmental theory, which argues that individuals can develop throu^ cumulative stages of ethical orientation and behavior (e.g. Hobbesian, Kantian, Rawlsian), such that leaders at later develop- mental stages (of whom there are empirically very few today) are more ethical. By contrast to a simple progressive model of ethical develop- ment, this paper shows that each developmental stage has both positive (light) and negative (shadow) aspects, which affect the ethical behaviors of leaders at that stage It also explores an unexpected result: later stage leaders can have more significantly negative effects than earlier stage leadership. Introduction hat makes a leader ethical? One answer to this question can be found in Wconstructive-developmental theory, which argues that individuals de- velop through cumulative stages that can be distinguished in terms of their epistemological assumptions, in terms of the behavior associated with each "worldview," and in terms of the ethical orientation of a person at that stage (Alexander et.al., 1990; Kegan, 1982; Kohlberg, 1981; Souvaine, Lahey & Kegan, 1990). Developmental theory has been successfully applied to organiza- tional settings and has illuminated the evolution of managers (Fisher, Merron & Torbert, 1987), leaders (Torbert 1989, 1994b; Fisher & Torbert, 1992), and or- ganizations (Greiner, 1972; Quinn & Cameron, 1983; Torbert, 1987a). Further, Torbert (1991) has shown that successive stages of personal development have an ethical logic that closely parallels the socio-historical development of ethical philosophies during the modern era; that is, each sequential ethical theory from Hobbes to Rousseau to Kant to Rawls explicitly outlines a coherent worldview held implicitly by persons at successively later developmental stages. -

Respondents. Attorney for National Employment Lawyers Association, Florida

Filing # 17020198 Electronically Filed 08/12/2014 05:15:30 PM RECEIVED, 8/12/2014 17:18:55, John A. Tomasino, Clerk, Supreme Court IN THE SUPREME COURT FOR THE STATE OF FLORIDA MARVIN CASTELLANOS, Petitioner, CASE NO.: SC13-2082 Lower Tribunal: 1D12-3639 vs. OJCC No. 09-027890GCC NEXT DOOR COMPANY/ AMERISURE INSURANCE CO., Respondents. BRIEF OF NATIONAL EMPLOYMENT LAWYERS ASSOCIATION, FLORIDA CHAPTER, AMICUS CURIAE, IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER LOUIS P. PFEFFER, ESQ. 250 South Central Blvd. Suite 205 Jupiter, FL 33458 561) 745 - 8011 [email protected] Attorney for National Employment Lawyers Association, Florida Chapter, as Amicus Curiae TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CITATIONS ........................ ............ii,iii,iv TABLE OF AUTHORITIES. .......... .... ........ .......... .......iv,v PRELIMINARY STATEMENT.. ............. ... ......... ... .............1 STATEMENT OF INTEREST............ .... ....................... ...1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT....................................... .. .2 INTRODUCTION........ ..................................... y.....3 ARGUMENT.................................... .........,........7 I. FLORIDA STATUTE 5440.34 (1) VIOLATES THE SEPARATION OF POWERS DOCTRINE AND THIS COURTS .INHERENT POWER TO ASSURE .A FAIR AND FUNCTIONING JUSTICE SYSTEM AND TO REGULATE ATTORNEYS AS OFFICERS OF THE COURT. .. ... .. ... .. .. .. .. .... ..7 A. STANDARD OF REVIEW ,., .... ... ., . ... .. .7 B. THE: SEPARATION OF POWERS PRECLUDES THE LEGISLATURE FROM ENCROACHING ON THE JUDICIAL BRANCH' S POWER TO ADMINISTER JUSTICE -

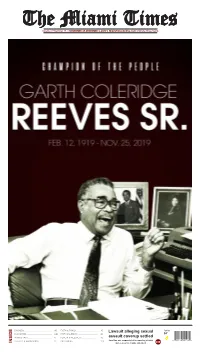

INSIDE and Coerced to Change Statement 10D Editorials Cartoons Opinions Letters

Volume 97 Number 15 | NOVEMBER 27-DECEMBER 3, 2019 | MiamiTimesOnline.com | Ninety-Three Cents BUSINESS ................................................. 8B FAITH & FAMILY ...................................... 7D Lawsuit alleging sexual Today CLASSIFIED ............................................. 11B FAITH CALENDAR ................................... 8D 84° IN GOOD TASTE ......................................... 1C HEALTH & WELLNESS ............................. 9D assault coverup settled LIFESTYLE HAPPENINGS ....................... 5C OBITUARIES ............................................. 12D Jane Doe was suspended after reporting attacks 8 90158 00100 0 INSIDE and coerced to change statement 10D Editorials Cartoons Opinions Letters VIEWPOINT BLACKS MUST CONTROL THEIR OWN DESTINY | NOVEMBER 27-DECEMBER 3, 2019 | MiamiTimesOnline.com MEMBER: National Newspaper Periodicals Postage Credo Of The Black Press Publisher Association paid at Miami, Florida Four Florida outrages: (ISSN 0739-0319) The Black Press believes that America MEMBER: The Newspaper POSTMASTER: Published Weekly at 900 NW 54th Street, can best lead the world from racial and Association of America Send address changes to Miami, Florida 33127-1818 national antagonism when it accords Subscription Rates: One Year THE MIAMI TIMES, The wealthy flourish, Post Office Box 270200 to every person, regardless of race, $65.00 – Two Year $120.00 P.O. Box 270200 Buena Vista Station, Miami, Florida 33127 creed or color, his or her human and Foreign $75.00 Buena Vista Station, Miami, FL Phone 305-694-6210 legal rights. Hating no person, fearing 7 percent sales tax for Florida residents 33127-0200 • 305-694-6210 the poor die H.E. SIGISMUND REEVES Founder, 1923-1968 no person, the Black Press strives to GARTH C. REEVES JR. Editor, 1972-1982 help every person in the firm belief that ith President Trump’s impeachment hearing domi- GARTH C. REEVES SR. -

Collier Fruit Growers Newsletter May 2015

COLLIER FRUIT GROWERS NEWSLETTER MAY 2015 The May 18th Speaker is Dr. Doug “Dougbug” Caldwell . Doug Caldwell will present and discuss his concept of a Collier Fruit Initiative as well as current invasive pests of Southwest Florida. DougBug is the go-to person on insects in Collier County and has a heart to promote fruit trees comfortable with our unique climate. DougBug is the commercial horticulturalist, entomologist and certified arborist at the UF/IFAS Collier County extension office. Next Meeting is May 18 at the Golden Gate Community Center, 4701 Golden Gate Parkway 7:00 pm for the tasting table and 7:30 pm for the meeting/program. BURDS’ NEST OF INFORMATION THIS and THAT FOR MAY: MANGOS: Now that the mango season is commencing, LATE mangos should be selectively pruned, (yes - there will be fruit on the tree) so as to have fruit again next year. Selectively pruning, so as not to lose all the fruit. If late mangos are pruned after the fruit is harvested, eg: late September or October, it raises the % chance of no fruit the next year. Late mangos are Keitt, Neelum, Palmer, Beverly, Wise, Cryder & Zillate Early mangos – Rosigold, Lemon Saigon, Glen, Manilita & Florigon, to name just a few! When the fruit has been harvested, fertilize with 0-0-18. This is recommended because of the minors in the formulae. Fertilizing with nitrogen will cause ‘jelly seed’ and poor quality fruit. Also, spray with micro nutrients just before the new growth has hardened off. Page 2 COLLIER FRUIT GROWERS NEWSLETTER RECIPE OF THE MONTH Meyer lemons are believed to be a natural hybrid of a lemon and a sweet orange. -

Ethnic Community, Party Politics, and the Cold War: the Political Ascendancy of Miami Cubans, 1980–2000

The Japanese Journal of American Studies, No. 23 (2012) Ethnic Community, Party Politics, and the Cold War: The Political Ascendancy of Miami Cubans, 1980–2000 Hideaki KAMI* INTRODUCTION Analysis of the implications of the rapidly growing Latino/Hispanic electorate for future U.S. political life is a relatively new project for his- torians and political scientists.1 Indeed, the literature on Latino politics has long considered their political underrepresentation as the central issue for research. Many scholars in the field have sought to explain how the burden of historical discrimination and antagonistic attitudes toward immigrants has discouraged these minorities from taking part in U.S. politics. Their studies have also explored how to overcome low voter turnout among Latinos and detect unfavorable institutional obstacles for voicing their opinions in government.2 However, partly due to previous academic efforts, the 1990s and 2000s have witnessed U.S. voters of Hispanic origin solidifying their role as a key constituency in U.S. pol- itics. An increasing number of politicians of Hispanic origin now hold elective offices at local, state, and national levels. Both the Republican and Democratic Parties have made intensive outreach efforts to seize the hearts and minds of these new voters, particularly by broadcasting spe- cific messages in Spanish media such as Univision.3 Although low *Graduate student, University of Tokyo and Ohio State University 185 186 HIDEAKI KAMI turnout among Latino voters and strong anti-immigrant sentiments among many non-Latino voters persist, the growing importance of the Latino electorate during the presidential elections has attracted increas- ing attention from inside and outside academic circles.4 Hence, in 2004, political scientist Rodolfo O. -

Caplinfrdrysdale Washington

Caplin s Dryidalc. Chartered One Thomas Circle. NW. Suite 1100 CaplinfrDrysdale Washington. DC 20005 202-862-5000 202-429-3301 fax A T I I I I E ! S wMMr.caplindryidale.com May 3,2004 Renee Salzmann, Esq. Office of General Counsel Federal Election Commission "0 999 E Street, N.W. xr > 5 Washington, D.C. 20463 ro O Re: MUR 5379 (Michael B. Fernandez) Dear Ms. Salzmann: On behalf of Respondent Michael B. Fernandez, I am hereby providing you with an amended statement of Mr. Fernandez. With the exception of the first phrase of paragraph five, the attached statement is identical to the statement dated September 18, 2003 submitted by Mr. Fernandez in response to the complaint filed by Peter Deutsch for Senate. Thus, paragraph five had stated, "In early March of 2002," but has now been corrected to state, "In early 2003." Please do not hesitate to call me with any questions. Sincerely Enclosure DOC* 217937 vl - OS/03/2004 Statement of Michael B. Fernandez 1. My name is Michael Fernandez. I am providing this statement in response to the complaint filed by Peter Deutsch for Senate in MUR 5379 against Mayor Alex Penelas. 2. I am Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of CAC-CarePlus Health Plans, Inc. ("CarePlus"). I also am the Chairman & CEO of CPHP Holdings, Inc. 0> and Chairman of Healthcare Atlantic Corporation. I have been a healthcare ^p executive for the better part of the past three decades. O •-I 3. I have lived in Miami since 1975. It is my home. It is where I raise my ^ family, make my living, and participate in community events. -

Israel's Qualitative Military Edge and Possible U.S. Arms Sales to the United Arab Emirates

Israel’s Qualitative Military Edge and Possible U.S. Arms Sales to the United Arab Emirates October 26, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46580 SUMMARY R46580 Israel’s Qualitative Military Edge and Possible October 26, 2020 U.S. Arms Sales to the United Arab Emirates Jeremy M. Sharp, This report provides background and analysis on a possible U.S. sale of the F-35 Joint Coordinator Strike Fighter and other advanced weaponry to the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in light Specialist in Middle of select U.S. policy considerations, including Israel’s Qualitative Military Edge (QME) Eastern Affairs over neighboring militaries, as well as concerns about an arms race and strategic competition with other arms suppliers. The F-35 is the United States’ most advanced Jim Zanotti, Coordinator stealthy, fifth generation combat aircraft. Its proposed sale, along with other items, to the Specialist in Middle UAE comes amidst broad support in Congress for an Israel-UAE normalization Eastern Affairs agreement announced in August 2020 and signed in September 2020. UAE’s National Day holiday, December 2, 2020, may be a target date for formalization of a U.S.-UAE Kenneth Katzman arms sale. Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs U.S.-UAE relations on security matters have been close for more than 20 years, and successive Administrations, with authorization from Congress, have sold the Emiratis Christina L. Arabia sophisticated U.S. weaponry, such as the F-16 Desert Falcon. Analyst in Security While many Members of Congress have praised closer Israeli-Emirati ties, some have Assistance, Security Cooperation and the expressed their views that the sale of the F-35 must not imperil Israel’s QME in the Global Arms Trade region. -

Florida's Paradox of Progress: an Examination of the Origins, Construction, and Impact of the Tamiami Trail

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2012 Florida's Paradox Of Progress: An Examination Of The Origins, Construction, And Impact Of The Tamiami Trail Mark Schellhammer University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Schellhammer, Mark, "Florida's Paradox Of Progress: An Examination Of The Origins, Construction, And Impact Of The Tamiami Trail" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2418. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2418 FLORIDA’S PARADOX OF PROGRESS: AN EXAMINATION OF THE ORIGINS, CONSTRUCTION, AND IMPACT OF THE TAMIAMI TRAIL by MARK DONALD SCHELLHAMMER II B.S. Florida State University, 2007 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2012 © 2012 by Mark Schellhammer II ii ABSTRACT This study illustrates the impact of the Tamiami Trail on the people and environment of South Florida through an examination of the road’s origins, construction and implementation. By exploring the motives behind building the highway, the subsequent assimilation of indigenous societies, the drastic population growth that occurred as a result of a propagated “Florida Dream”, and the environmental decline of the surrounding Everglades, this analysis reveals that the Tamiami Trail is viewed today through a much different context than that of the road’s builders and promoters in the early twentieth century. -

BOCA RATON NEWS Vol

BOCA RATON NEWS Vol. 1.1 No. 101 Sunday, November 6/1966 10$ 65% of m Seven Points Are Listed On CIP Ballot (Related Editorials and Cartoon, Page 4A) Boca Raton's special referen- dum on capital improvements is expected to draw votes from more than 65 per cent of the 7,260 registered freeholders Tuesday. The predicted 4,700 will do something they haven't done in two years — use a hand ballot. James Becker, left, took over as president of Boca Raton Chamb- Since only freeholders — those er of Commerce at the group's annual installation banquet in the who own and pay taxes on prop- erty — are eligible, the ballot Boca Raton Hotel and Club. Retiring president William Worsham could not be placed on the voting received a certificate of appreciation for his past service during machine, as all voters are elig- the ceremony. ible for state and county elec- tions. During the past six weeks, a great deal of interest has been The "get out the vote" drive has a special who has a son serving in Viet Nam, had this re- raised on the seven-point CIP meaning for Bill Bragg and he's doing his best minder painted on the back of his automobile. Student Polls Show program. Mayor Pat Honchell, to pass the message on to everyone else. Bragg, Councilman Bernard E. Turn- er, City department heads, and James Becker, who headed the Close State Races Garden Apartments Committee, have spoken at many of the ser- lican Sweep Predicted With the state gubernatorial Kirk's favor in the FAU poll. -

Combatir Juego De La Bolita

VIERNES, 16 BE MAYO BE 1958 MARIO LAS AMERICAS—IPág. 5 Semana de Cámara de Comercio Será Carta Abierta al Juez Giblin de El nego- süüísNEGRONI Mayo 18 al 24 conocido hombre de ropa, peleando y muriendo por cios puertorriqueño, residente De nuestra bandera Américana como acuerdo con la actuación del por varios años en Miami, don proyectados Leroy Collins, escalones en nue» Gobernador la Jun- Francisco Grovas, nos ha entre- tros deseos de los ta de Comisionados del Condado vencer a encn* il Hombre Necesita m Purgante gado, con el ruego de su pu- cijados en su taita de corage y do Dade ha proclamado oficialmente blicación, la siguiente Carta bilidad? Honor la mayo Vuestro estarí* Circuito semana del 18 al 24 de “Se Abierta dirigid:- al Juez Giblin, rindiendo un gran El Hon. Don Vicente Giblin, juez del Tribunal de mana de tributo a nues- la Cámara de Comercio”, de la Corte,de Circuito de Dade:. tros amados muertos en de Dade, necesita un purgante a toda prisa. en todo este sector. línea coi Honorable Juez Vicente Giblin nuestra tradición americana. El español lo mantiene indigestado de manera tal, que Hace poco, el Jefe del Ejecutivo Miami, Fia. No solamente debemos predicar, del Estado de Florida, dedicó la se- debemos actuar ha entrado en la etapa del delirio y puede hacer crisis en “apreciación Estimado Juez Giblin: como verdadero* mana a la de los es- regañando ciudadanos americanos eualquier momento. voluntarios Su actitud a nuestro fuerzos de los miem- compatriota el puertorriqueño Su seguro servidor, bros de estas organizaciones y en Don Vicente presentó su lado de la historia a través de la Eleuterio González y metiéndole a FRANCISCO GROVAS , reconocimiento de sus resultados la járce cuando deponía televisión y ratificó que continuará actuando de la misma en alcanzar el interés l como mejor del testigo ante V.H., a con los que no sepan inglés o pretendan no saberlo, Florida, debido su fal- manera Estado de en los sectores ta de conocimiento del idioma in- El que la mayoría de los latinos en que se desenvuelven”.