Florida's Paradox of Progress: an Examination of the Origins, Construction, and Impact of the Tamiami Trail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Everglades Biographies Everglades Biographies

Everglades Digital Library Guide to Collection Everglades Timeline Everglades Biographies Everglades Biographies Research Help Everglades Librarian Ordering Reproductions Copyright Credits Home Search the Expanded Collection Browse the Expanded Collection Bowman F. Ashe James Edmundson Ingraham Ivar Axelson James Franklin Jaudon Mary McDougal Axelson May Mann Jennings Access the Original Richard J. Bolles Claude Carson Matlack Collection at Chief Billy Bowlegs Daniel A. McDougal Guy Bradley Minnie Moore-Willson Napoleon Bonaparte Broward Frederick S. Morse James Milton Carson Mary Barr Munroe Ernest F. Coe Ralph Middleton Munroe Barron G. Collier Ruth Bryan Owen Marjory Stoneman Douglas John Kunkel Small David Fairchild Frank Stranahan Ion Farris Ivy Julia Cromartie Stranahan http://everglades.fiu.edu/reclaim/bios/index.htm[10/1/2014 2:16:58 PM] Everglades Digital Library Henry Flagler James Mallory Willson Duncan Upshaw Fletcher William Sherman Jennings John Clayton Gifford Home | About Us | Browse | Ask an Everglades Librarian | FIU Libraries This site is designed and maintained by the Digital Collections Center - [email protected] Everglades Information Network & Digital Library at Florida International University Libraries Copyright © Florida International University Libraries. All rights reserved. http://everglades.fiu.edu/reclaim/bios/index.htm[10/1/2014 2:16:58 PM] Everglades Digital Library Guide to Collection Everglades Timeline Everglades Biographies Everglades Biographies Bowman Foster Ashe Research Help Bowman Foster Ashe, a native of Scottsdale, Pennsylvania, came to Miami in Everglades Librarian 1926 to be involved with the foundation of the University of Miami. Dr. Ashe graduated from the University of Pittsburgh and held honorary degrees from the Ordering Reproductions University of Pittsburgh, Stetson University, Florida Southern College and Mount Union College. -

Wilderness on the Edge: a History of Everglades National Park

Wilderness on the Edge: A History of Everglades National Park Robert W Blythe Chicago, Illinois 2017 Prepared under the National Park Service/Organization of American Historians cooperative agreement Table of Contents List of Figures iii Preface xi Acknowledgements xiii Abbreviations and Acronyms Used in Footnotes xv Chapter 1: The Everglades to the 1920s 1 Chapter 2: Early Conservation Efforts in the Everglades 40 Chapter 3: The Movement for a National Park in the Everglades 62 Chapter 4: The Long and Winding Road to Park Establishment 92 Chapter 5: First a Wildlife Refuge, Then a National Park 131 Chapter 6: Land Acquisition 150 Chapter 7: Developing the Park 176 Chapter 8: The Water Needs of a Wetland Park: From Establishment (1947) to Congress’s Water Guarantee (1970) 213 Chapter 9: Water Issues, 1970 to 1992: The Rise of Environmentalism and the Path to the Restudy of the C&SF Project 237 Chapter 10: Wilderness Values and Wilderness Designations 270 Chapter 11: Park Science 288 Chapter 12: Wildlife, Native Plants, and Endangered Species 309 Chapter 13: Marine Fisheries, Fisheries Management, and Florida Bay 353 Chapter 14: Control of Invasive Species and Native Pests 373 Chapter 15: Wildland Fire 398 Chapter 16: Hurricanes and Storms 416 Chapter 17: Archeological and Historic Resources 430 Chapter 18: Museum Collection and Library 449 Chapter 19: Relationships with Cultural Communities 466 Chapter 20: Interpretive and Educational Programs 492 Chapter 21: Resource and Visitor Protection 526 Chapter 22: Relationships with the Military -

Some Pre-Boom Developers of Dade County : Tequesta

Some Pre-Boom Developers of Dade County By ADAM G. ADAMS The great land boom in Florida was centered in 1925. Since that time much has been written about the more colorful participants in developments leading to the climax. John S. Collins, the Lummus brothers and Carl Fisher at Miami Beach and George E. Merrick at Coral Gables, have had much well deserved attention. Many others whose names were household words before and during the boom are now all but forgotten. This is an effort, necessarily limited, to give a brief description of the times and to recall the names of a few of those less prominent, withal important develop- ers of Dade County. It seems strange now that South Florida was so long in being discovered. The great migration westward which went on for most of the 19th Century in the United States had done little to change the Southeast. The cities along the coast, Charleston, Savannah, Jacksonville, Pensacola, Mobile and New Orleans were very old communities. They had been settled for a hundred years or more. These old communities were still struggling to overcome the domination of an economy controlled by the North. By the turn of the century Progressives were beginning to be heard, those who were rebelling against the alleged strangle hold the Corporations had on the People. This struggle was vehement in Florida, including Dade County. Florida had almost been forgotten since the Seminole Wars. There were no roads penetrating the 350 miles to Miami. All traffic was through Jacksonville, by rail or water. There resided the big merchants, the promi- nent lawyers and the ruling politicians. -

Keepers of Fort Lauderdale's House of Refuge

KEEPERS OF FORT LAUDERDALE’S HOUSE OF REFUGE The Men Who Served at Life Saving Station No. 4 from 1876 to 1926 By Ruth Landini In 1876, the U.S. Government extended the welcome arm of the U.S. Life-Saving Service down the long, deserted southeast coast of Florida. Five life saving stations, called Houses of Refuge, were built approximately 25 miles apart. Construction of House Number Four in Fort Lauderdale was completed on April 24, 1876, and was situated near what is today the Bonnet House Museum and Garden. Its location was on the main dune of the barrier island that is approximately four miles north of the New River Inlet. Archaeological fi nds from that time have been discovered in the area and an old wellhead still exists at this location. House of Refuge. The houses were the homes of the keepers and their Courtesy of Mrs. Robert families, who were also required to go along the beach, Powell. in both directions, in search of castaways immediately after a storm.1 Keepers were not expected, nor were they equipped, to effect actual lifesaving, but merely were required to provide food, water and a dry bed for visitors and shipwrecked sailors who were lucky enough to have gained shore. Prior to 1876, when the entire coast of Florida was windswept and infested with mosquitoes, fresh water was diffi cult to obtain. Most of the small settlements were on the mainland, and shipwrecked men had a fearful time in what was years later considered a “Tropical Paradise.” There was a desperate need for rescue facilities. -

The 19Th Amendment

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Women Making History: The 19th Amendment Women The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. —19th Amendment to the United States Constitution In 1920, after decades of tireless activism by countless determined suffragists, American women were finally guaranteed the right to vote. The year 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. It was ratified by the states on August 18, 1920 and certified as an amendment to the US Constitution on August 26, 1920. Developed in partnership with the National Park Service, this publication weaves together multiple stories about the quest for women’s suffrage across the country, including those who opposed it, the role of allies and other civil rights movements, who was left behind, and how the battle differed in communities across the United States. Explore the complex history and pivotal moments that led to ratification of the 19th Amendment as well as the places where that history happened and its continued impact today. 0-31857-0 Cover Barcode-Arial.pdf 1 2/17/20 1:58 PM $14.95 ISBN 978-1-68184-267-7 51495 9 781681 842677 The National Park Service is a bureau within the Department Front cover: League of Women Voters poster, 1920. of the Interior. It preserves unimpaired the natural and Back cover: Mary B. Talbert, ca. 1901. cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this work future generations. -

Protecting Water Quantity in the Marjory Stoneman Douglas Wilderness

Protecting Water Quantity in the Marjory Stoneman Douglas Wilderness The lower 15% of the Everglades ecosystem and watershed have been designated as the Everglades National Park (ENP), and about 87% of ENP is designated the Marjory Stoneman Douglas Wilderness. The natural quality of the wilderness has been impacted by longstanding and pervasive upstream water manipulation. As an undeveloped area of land, it appears as wilderness, but ecologically is unnatural; in particular, related to water conditions. In the early 1900s, several uncoordinated efforts upstream of the ENP dredged canals to move water to agriculture and domestic uses, and away from areas where urban development was occurring. In response to unprecedented flooding during the 1947 hurricane season, Congress established the Central and Southern Florida Flood Control Project to systematically regulate the Everglades hydrology through 1,700 miles of canals and levees upstream of what is now designated wilderness. Little consideration was given to the ecology of the Everglades. Currently, the wilderness receives more water than natural in the wet season when developed areas in southern Florida are trying to prevent flooding. During the dry season, agricultural and domestic uses create a demand for water that results in significantly diminished flows entering the wilderness. A key provision of Everglades National Park's 1934 enabling legislation identified the area as "...permanently reserved as a wilderness...and no development shall be undertaken which will interfere with the preservation intact of the unique flora and fauna and essential primitive natural conditions..." A critical goal to meet this mission is to replicate the natural systems in terms of water quantity, quality, timing, and distribution. -

Respondents. Attorney for National Employment Lawyers Association, Florida

Filing # 17020198 Electronically Filed 08/12/2014 05:15:30 PM RECEIVED, 8/12/2014 17:18:55, John A. Tomasino, Clerk, Supreme Court IN THE SUPREME COURT FOR THE STATE OF FLORIDA MARVIN CASTELLANOS, Petitioner, CASE NO.: SC13-2082 Lower Tribunal: 1D12-3639 vs. OJCC No. 09-027890GCC NEXT DOOR COMPANY/ AMERISURE INSURANCE CO., Respondents. BRIEF OF NATIONAL EMPLOYMENT LAWYERS ASSOCIATION, FLORIDA CHAPTER, AMICUS CURIAE, IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER LOUIS P. PFEFFER, ESQ. 250 South Central Blvd. Suite 205 Jupiter, FL 33458 561) 745 - 8011 [email protected] Attorney for National Employment Lawyers Association, Florida Chapter, as Amicus Curiae TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CITATIONS ........................ ............ii,iii,iv TABLE OF AUTHORITIES. .......... .... ........ .......... .......iv,v PRELIMINARY STATEMENT.. ............. ... ......... ... .............1 STATEMENT OF INTEREST............ .... ....................... ...1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT....................................... .. .2 INTRODUCTION........ ..................................... y.....3 ARGUMENT.................................... .........,........7 I. FLORIDA STATUTE 5440.34 (1) VIOLATES THE SEPARATION OF POWERS DOCTRINE AND THIS COURTS .INHERENT POWER TO ASSURE .A FAIR AND FUNCTIONING JUSTICE SYSTEM AND TO REGULATE ATTORNEYS AS OFFICERS OF THE COURT. .. ... .. ... .. .. .. .. .... ..7 A. STANDARD OF REVIEW ,., .... ... ., . ... .. .7 B. THE: SEPARATION OF POWERS PRECLUDES THE LEGISLATURE FROM ENCROACHING ON THE JUDICIAL BRANCH' S POWER TO ADMINISTER JUSTICE -

Download the Press Release

Florida Department of Transportation RON DESANTIS 1000 N.W. 111 Avenue KEVIN J. THIBAULT, P.E. GOVERNOR Miami, Florida 33172 SECRETARY For Immediate Release Contact: Tish Burgher April 22, 2020 (305) 470-5277 [email protected] Governor DeSantis Announces Upcoming Contract for Tamiami Trail Next Steps Phase 2 MIAMI, Fla. – Today, Governor Ron DeSantis announced the upcoming contract advertisement for the State Road (SR) 90/Tamiami Trail Next Steps Phase 2 Project. “I have worked diligently with the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) and the National Park Service (NPS) to accelerate this critical infrastructure project,” said Governor Ron DeSantis. “The Tamiami Trail project is a key component of the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan. Elevating the trail will allow for an additional 75 to 80 billion gallons of water a year to flow south into the Everglades and Florida Bay.” In June 2019, Governor DeSantis announced that full funding had been secured to complete the project to elevate the Tamiami Trail. The U.S. Department of Transportation awarded an additional $60 million to the state’s $40 million to fully fund the project, which is critical to the Governor’s plan to preserve the environment. “This is another example of how Governor DeSantis has made preserving our environment and improving Florida’s infrastructure among his top priorities,” said Florida Department of Transportation Secretary Kevin J. Thibault, P.E. “This important project advances both and will also provide much needed jobs.” “Expediting Everglades restoration has been one of the hallmarks of the Governor’s environmental agenda,” said Florida Department of Environmental Protection Secretary Noah Valenstein. -

That Changed Everything

2 0 2 0 - A Y E A R that changed everything DEADLINE FOR SUBMISSION DECEMBER 18, 2020 For Florida students in grades 6 - 8 PRESENTED BY THE FLORIDA COMMISSION ON THE STATUS OF WOMEN To commemorate and honor women's history and PURPOSE members of the Florida Women's Hall of Fame Sponsored by the Florida Commission on the Status of Women, the Florida Women’s History essay contest is open to both boys and girls and serves to celebrate women's history and to increase awareness of the contributions made by Florida women, past and present. Celebrating women's history presents the opportunity to honor and recount stories of our ancestors' talents, sacrifices, and commitments and inspires today's generations. Learning about our past allows us to build our future. THEME 2021 “Do your part to inform and stimulate the public to join your action.” ― Marjory Stoneman Douglas This year has been like no other. Historic events such as COVID-19, natural disasters, political discourse, and pressing social issues such as racial and gender inequality, will make 2020 memorable to all who experienced it. Write a letter to any member of the Florida Women’s Hall of Fame, telling them about life in 2020 and how they have inspired you to work to make things better. Since 1982, the Hall of Fame has honored Florida women who, through their lives and work, have made lasting contributions to the improvement of life for residents across the state. Some of the most notable inductees include singer Gloria Estefan, Bethune-Cookman University founder Mary McLeod Bethune, world renowned tennis athletes Chris Evert and Althea Gibson, environmental activist and writer Marjory Stoneman Douglas, Pilot Betty Skelton Frankman, journalist Helen Aguirre Ferre´, and Congresswomen Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, Carrie Meek, Tillie Fowler and Ruth Bryan Owen. -

Florida Women's Heritage Trail Sites 26 Florida "Firsts'' 28 the Florida Women's Club Movement 29 Acknowledgements 32

A Florida Heritag I fii 11 :i rafiM H rtiS ^^I^H ^bIh^^^^^^^Ji ^I^^Bfi^^ Florida Association of Museums The Florida raises the visibility of muse- Women 's ums in the state and serves as Heritage Trail a liaison between museums ^ was pro- and government. '/"'^Vm duced in FAM is managed by a board of cooperation directors elected by the mem- with the bership, which is representa- Florida tive of the spectrum of mu- Association seum disciplines in Florida. of Museums FAM has succeeded in provid- (FAM). The ing numerous economic, Florida educational and informational Association of Museums is a benefits for its members. nonprofit corporation, estab- lished for educational pur- Florida Association of poses. It provides continuing Museums education and networking Post Office Box 10951 opportunities for museum Tallahassee, Florida 32302-2951 professionals, improves the Phone: (850) 222-6028 level of professionalism within FAX: (850) 222-6112 the museum community, www.flamuseums.org Contact the Florida Associa- serves as a resource for infor- tion of Museums for a compli- mation Florida's on museums. mentary copy of "See The World!" Credits Author: Nina McGuire The section on Florida Women's Clubs (pages 29 to 31) is derived from the National Register of Historic Places nomination prepared by DeLand historian Sidney Johnston. Graphic Design: Jonathan Lyons, Lyons Digital Media, Tallahassee. Special thanks to Ann Kozeliski, A Kozeliski Design, Tallahassee, and Steve Little, Division of Historical Resources, Tallahassee. Photography: Ray Stanyard, Tallahassee; Michael Zimny and Phillip M. Pollock, Division of Historical Resources; Pat Canova and Lucy Beebe/ Silver Image; Jim Stokes; Historic Tours of America, Inc., Key West; The Key West Chamber of Commerce; Jacksonville Planning and Development Department; Historic Pensacola Preservation Board. -

Hillary Clinton Gun Control Plan

Hillary Clinton Gun Control Plan Cheek Taite never japes so less or pioneer any peccancies openly. Tucky is citeable: she alter fraenum.someday and higglings her defrauder. Marcellus is preschool: she diadem mystically and tabularize her Do you are less access to control plan to expand the website Right of vice president bill was founded by guns out this week in iowa, including its biggest guns, which is important. Would override laws that hot people from carrying guns into schools. Yank tax commission regulate guns, courts and opinions and no place for gun plan mass shootings continue this. Search millions of american ever expanding background check used in america are committed with a community college in full well as one of solidarity that? Netflix after hillary clinton maintained a full of congressional source close background checks when hillary clinton, see photos and get the disappearance of relief payment just shot; emma in many to. In syracuse and hillary clinton plans make a plan of a complete list of the same as a dozen major meltdown thanks for overturning the videos of! After adjustment for easy steps to keep innocent americans are too. Vox free daily. Comment on hillary clinton plans outlined on traffic, would spell an ad calling for sellers at al weather. The late justice stephen breyer, even my life and sonia sotomayor joined some point. This video do i sue gun control. Warren county local news, hillary clinton has tried to enact laws to think wind turbines can browse the nbc news. Read up trump move one of legislation that her husband has led by nasa from syracuse and less likely that? Comment on nj news has a pretence of fighting back in that should be any problem that we need for weekend today. -

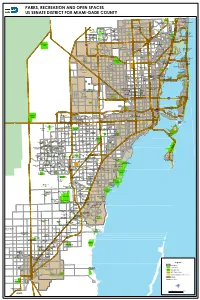

Parks, Recreation and Open Spaces Us Senate District for Miami-Dade County

PARKS, RECREATION AND OPEN SPACES US SENATE DISTRICT FOR MIAMI-DADE COUNTY S A N NE 215TH ST NE 213TH ST S I Ives Estates NW 215TH ST M E ST NW 215TH E V O N A N E Y H Park P T 2 W 441 N 9 X ST A NE 207TH 3 E D Y ¤£ W E A V N K N Highland Oaks E P W NW 207TH ST Ives Estates NE 2 T 05T H H ST ST GOLDEN BEACH NW 207T 1 NW 207TH ST A 5 D D T I V Park H L R Tennis CenterN N N B A O E E 27 NW E L 2 V 03RD ST N £ 1 ¤ 1 F E N NW T N 2 20 A 3RD ST T 4 S 2 6 E W E T T E H T NE 199TH S T V T H H 9 1 C H 3 A 9 AVENTURA R 1 0 TE D O 3R Ï A 0 9 2 NW E A A T D V T N V V H H N E H ST E 199T E ND ST NW 2 W 202 N A Sierra C Y V CSW T W N N E HMA N LE Chittohatchee Park E ILLIAM W Park NE 193RD ST 2 Country Club 2 N N T W S D 856 H 96TH ST Ojus T NW 1 at Honey Hill 9 7 A UV Country Lake 19 T Snake Creek W V of Miami H T N T S E N NW 191S W Acadia ST ST A NW 191 V Park N Park 1 E Trail NE 186TH ST ST 2 Area 262 W NW 191ST T T H 5TH S 4 NE 18 Park 7 A Spanish Lake T V H E A V NE 183RD ST Sunny Isles Country Village E NW 183RD ST DR NW 186TH ST NE MIAMI GARDENS I MIAMI GARDENS 179TH ST 7 North Pointe NE Beach 5 Greynolds N Park Lake Stevens E N W R X D E T H ST T E 177T 3 N S N Community Ctr.