4X100m Relay Strategies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Energy and Training Module ITU Competitive Coach

37 energy and training module ITU Competitive Coach Produced by the International Triathlon Union, 2007 38 39 energy & training Have you ever wondered why some athletes shoot off the start line while others take a moment to react? Have you every experienced a “burning” sensation in your muscles on the bike? Have athletes ever claimed they could ‘keep going forever!’? All of these situations involve the use of energy in the body. Any activity the body performs requires work and work requires energy. A molecule called ATP (adenosine triphosphate) is the “energy currency” of the body. ATP powers most cellular processes that require energy including muscle contraction required for sport performance. Where does ATP come from and how is it used? ATP is produced by the breakdown of fuel molecules—carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. During physical activity, three different processes work to split ATP molecules, which release energy for muscles to use in contraction, force production, and ultimately sport performance. These processes, or “energy systems”, act as pathways for the production of energy in sport. The intensity and duration of physical activity determines which pathway acts as the dominant fuel source. Immediate energy system Fuel sources ATP Sport E.g. carbohydrates, energy performance proteins, fats “currency” Short term energy system E.g. swimming, cycling, running, transitions Long term energy system During what parts of a triathlon might athletes use powerful, short, bursts of speed? 1 2 What duration, intensity, and type of activities in a triathlon cause muscles to “burn”? When in a triathlon do athletes have to perform an action repeatedly for longer than 10 or 15 3 minutes at a moderate pace? 40 energy systems Long Term (Aerobic) System The long term system produces energy through aerobic (with oxygen) pathways. -

Shoes Approved by World Athletics - As at 01 October 2021

Shoes Approved by World Athletics - as at 01 October 2021 1. This list is primarily a list concerns shoes that which have been assessed by World Athletics to date. 2. The assessment and whether a shoe is approved or not is determined by several different factors as set out in Technical Rule 5. 3. The list is not a complete list of every shoe that has ever been worn by an athlete. If a shoe is not on the list, it can be because a manufacturer has failed to submit the shoe, it has not been approved or is an old model / shoe. Any shoe from before 1 January 2016 is deemed to meet the technical requirements of Technical Rule 5 and does not need to be approved unless requested This deemed approval does not prejudice the rights of World Athletics or Referees set out in the Rules and Regulations. 4. Any shoe in the list highlighted in blue is a development shoe to be worn only by specific athletes at specific competitions within the period stated. NON-SPIKE SHOES Shoe Company Model Track up to 800m* Track from 800m HJ, PV, LJ, SP, DT, HT, JT TJ Road* Cross-C Development Shoe *not including 800m *incl. track RW start date end date ≤ 20mm ≤ 25mm ≤ 20mm ≤ 25mm ≤ 40mm ≤ 25mm 361 Degrees Flame NO NO NO NOYES NO Adidas Adizero Adios 3 NO YES NO YES YES YES Adidas Adizero Adios 4 NO YES NO YES YES YES Adidas Adizero Adios 5 NO YES NO YES YES YES Adidas Adizero Adios 6 NO YES NO YES YES YES Adidas Adizero Adios Pro NO NO NO NOYES NO Adidas Adizero Adios Pro 2 NO NO NO NOYES NO Adidas Adizero Boston 8 NO NO NO NOYES NO Adidas Adizero Boston 9 NO NO NO -

A Mathematical Analysis of the 4 X 100 M Relay

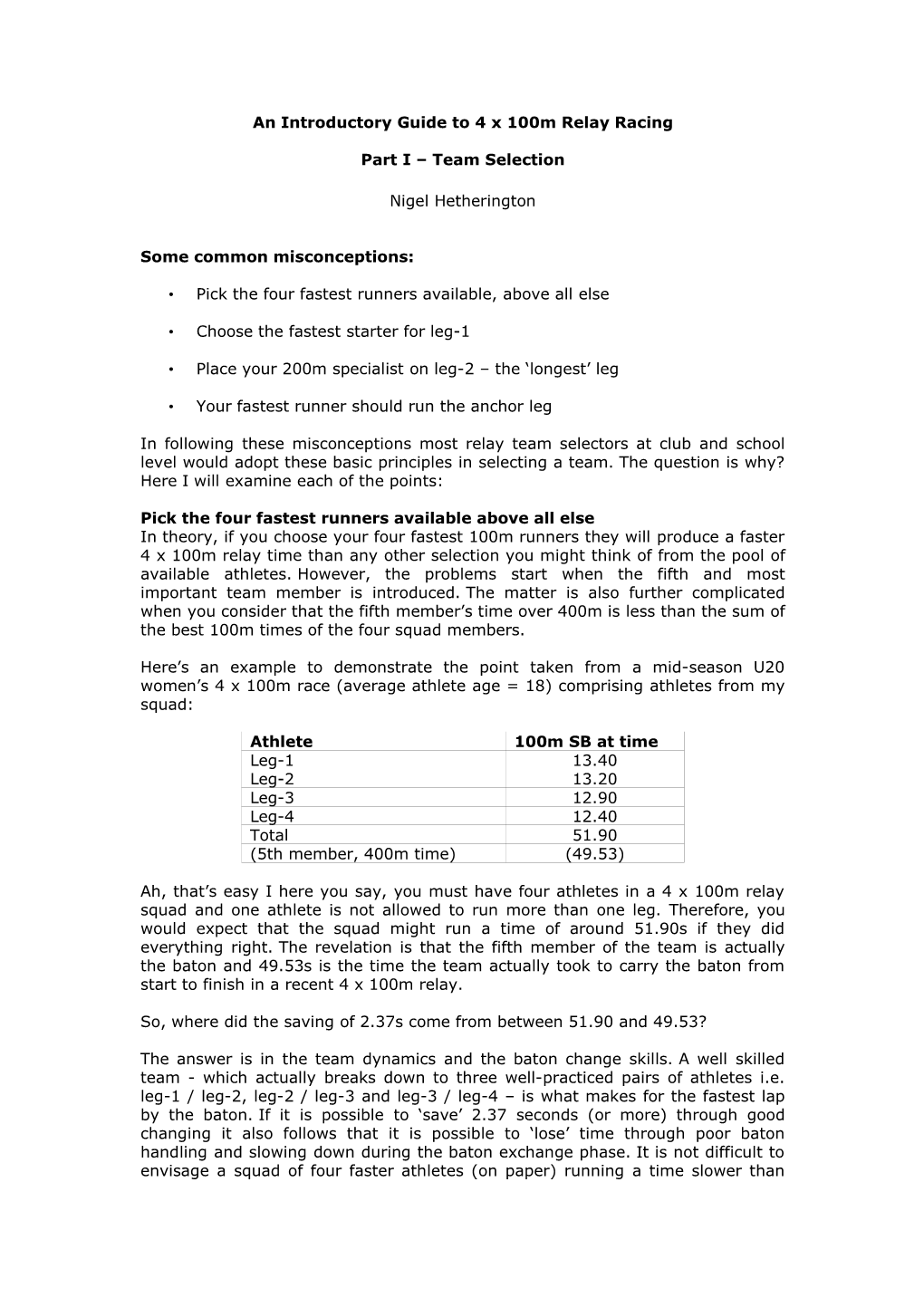

Journal of Sports Sciences, 2002, 20, 369± 381 A mathematical analysis of the 4 ´ 100 m relay A.J. WARD-SMITH and P.F. RADFORD* Department of Sport Sciences, Brunel University, Osterley Campus, Borough Road, Isleworth, Middlesex TW7 5DU, UK Accepted 19 November 2001 In this study, we examined aspects of the 4 ´ 100 m relay that are amenable to mathematical analysis. We looked at factors that aþ ect the time required to complete the relay, focusing on the performance of elite male athletes. Factors over which the individual athletes, and the team coach, can exercise some control are: the starting positions of the runners on legs 2, 3 and 4, the positions at which baton exchanges occur, the free distances at the baton exchanges and the running order of the athletes. The lane draw is shown to have an important in¯ uence on the relay time, although it is outside the control of the team coach. Teams drawn in the outside lanes bene® t from the inverse relation between bend radius of curvature and running speed. For teams composed of athletes with diþ erent times over 100 m, we show that the fastest relay times are achieved with the fastest athlete taking the ® rst leg, with the slowest two runners allocated to the ® nal two legs. Keywords: athletics, running, sprinting. Introduction allowance is made for bend curvature in the layout of the starting lines, which are staggered across the eight The aim of this study was to examine aspects of the lanes of the track. These rules eþ ectively determine the 4 ´ 100 m relay that are amenable to mathematical distances run by the runners on each of the four legs. -

10Th ANNUAL KEYS 100 ULTRAMARATHON Bob Becker, Race Director

10th ANNUAL KEYS 100 ULTRAMARATHON Bob Becker, Race Director The “10th Annual” KEYS100. When five of us ran the length of the Keys in 2007 to see if a 100-mile race might be possible across all those islands, I could not imagine that we would come this far. In these past ten years since the first actual race in 2008, we’ve seen participation in our sport of ultramarathon running expand exponentially throughout Florida, with a proliferation of ultra-distance races every month of the year. Today, nearly all runners, from 5k to the marathon, actually know what an “ultra” is, which was not the case just a short time ago. Our sport has traditionally been identified with trail running, mostly in the American west. The number of ultramarathon road races—especially of 100 miles or longer—is very limited throughout the country. But today, at many trail and road ultramarathons around the country, Florida runners are frequently the second or third largest contingent, a real testament to how far the sport has come right here at home in just these few years. KEYS100 has grown, too, from 131 runners in 2008 to more than a thousand each of the past three years. We run 100 miles as individuals or in teams, plus individual races of 50 miles and 50 kilometers (31 miles). On May 20-21, 2017, bike paths, pedestrian bridges, the parallel “old road” and some miles along the Overseas Highway road shoulder from Key Largo to Key West contained some real movers and shakers, outstanding athletes making their way towards the finish line on Higgs Beach. -

Marathon Relay Information Packet Pickup

MARATHON RELAY INFORMATION PACKET PICKUP Your team's packet will be available at the packet pick-up location on the day before the race and at the Fairgrounds the day of the race. Only the captain or one team representative needs to attend packet pick-up. If you can't make Friday packet pick-up, be sure to allow your team enough time before the start of the race to pick it up. Please note that race day packet pick-up is not at the starting line – it will be located at the packet pick-up area near the main entrance of the Fairgrounds. REGISTRATION POLICIES Age Restrictions All runners under the age of 18 must have a parent or legal guardian sign a waiver. Individuals under the age of 12 are not permitted to run in the State Fair Marathon Relay. Refunds Entry fees are non-refundable. The entry fee for this year's event will not transfer to next year's event. Disqualifications The State Fair Marathon Relay reserves the right to reject any entry and to disqualify and bar any individual or team from the race. This rejection/disqualification may be based on, but is not limited to, non-payment of race fees, competing with an unofficial number, competing with an official number assigned to another competitor without completing the proper forms, crossing the finish line without having completed the entire course, or providing false information on race entry forms. The State Fair Marathon Relay reserves the right to change the details of the race at any time. -

The Using of Modern Technologies in Orienteering

The using of modern technologies in orienteering Michal Frainšic1, Petr Špicar2, Ludmila Fialová2 1 Department of Outdoor activities, Faculty of Physical Education and Sport, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic 2 Department of Pedagogy, Psychology and Didactics of sport, Faculty of Physical Education and Sport, Char- les University, Prague, Czech Republic Abstract The article deals with introduction and contribution of modern technologies used in a sport branch of ori- enteering sports in comparison with the past when these technologies were not used. Modern technologies contributed to expansion of orienteering sports. They made this branch of sport more attractive for both - com- petitors and spectators. Facilities like SPORTident, Trac-Trac, Emit and Racom transfered on-line results from race to competitors and spectators, who are in the race center. Thanks to those facilities spectators can also watch the race on-line on TV or on the Internet. Program OCAD made the preparation of orienteering maps and tracks faster and more effective. Modern technologies also speeded up the process of race preparation. Key words Emit, OCAD, Oorg, Open Orienteering Mapper, Purple Pen, Orienteering organiser, orienteering, orientee- ring sports, Racom, SPORTident, Trac-Trac. Souhrn Článek se věnuje představení a přínosu moderních technologií využívaných ve sportovních odvětvích orien- tačních sportů v porovnání s dobou minulou, kdy tyto technologie ještě využívány nebyly. Moderní technolo- gie se zasloužily o rozvoj orientačních sportů, toto sportovní odvětví zatraktivnily a to jak závodníkům, tak i široké veřejnosti. Zařízení SPORTident, Trac-Trac, Emit a Racom přináší okamžité výsledky a umožňují on-line přenosy výsledků trenérům, závodníkům na shromaždišti či divákům u televizní obrazovky. -

Best Workouts· .Cross Country Journal

Best Workouts· .from the .Cross Country Journal Best Workouts from the Cross Country Journal Compiled from the first t-welve volumes of the Journal © 1995, IDEA, Inc. Publisher of the Cross Country Journal Contents by Subject Cross Training "Swimming Pool Training Program," Finanger, Kent. 8 "Cross-training to a Higher Fitness Level," Helton, Jim 24 "Peaking in the Water? You Bet!," Reeves, Ken 33 Easy Day Workouts "Creative Easy-Day Workouts," Long & Rieken 5 Favorite Workouts "Runners' Favorite Workouts," panel of experienced runners : 12 "Coaches' Favorite Hard-Day Workouts," panel of experienced coaches 13 "Our Favorite Workout," Christopher, Deb 44 Fun Workouts "Distance Runners' Decathlon.tAnderson-Iordan, Teri :..3 "Rambo Run," Weston, Gary 9 "Interesting Summer Work-out5," panel of experienced coaches 10 "Taking the Edge Off Hard Workouts," panel of experienced coaches 15 "Rainbow Relays," Weston, Gary : 18 "Scavenger Hunt," Weston, Gary 19 "IDO Relays," Weston, Gary 20 "Sharks and Guppies," Thompson,. Dale 22 "Rambo Run, Ohio Style," Eleo, Larry 23 "Fun Activity," Lawton, Phil , 26 "Cross Country Flickerball," Thompson, Dale 27 "Halloween Run," Reeves, Ken 28 "Creative Workout," Weitzel, Rich ~ 29 "Spice Up Practice With Wacky Relays," Gerenscer, John ~ - .45 "Pre-Meet-Day Fun-Runs," Klock, Ty -46 i Cross Country Products Available from IDEA, Ine., Publishers of the CROSS COUNTRY JOURNAL AAF/CIF Cross Country Manual (book) Best of the Cross Country Journal, in three volumes (books) Buffaloes, Running with the by Chris Lear (book) Cartoons, The Best of the CCJ, in three sets (loose) CCMEET: the computer program to score actual meets (disc) Coaches' Forum, Fifteen Years of the (book) Coaching Cross Country .. -

Track and Field Pre-Meet Notes

2021 TRACK AND FIELD PRE-MEET NOTES HIGHLIGHTS OF RULES CHANGES 01 02 03 04 Exchange Zones: Assisting Other Competitors: Long & Triple Jump Pits: Runways: Exchange Zones will be 30 A competitor should not be For pits constructed after It is illegal to run backward meters long for incoming penalized for helping another 2019, the length of the pit or in the opposite direction competitors running 200 competitor who is distressed shall be at least 23 feet (non-legal direction) on a meters or less. or injured when no (7 meters). horizontal jump, pole vault advantage is gained by the or javelin runway. competitor who is assisting. 2021 PRE-MEET NOTES IN THIS ISSUE: 1 RULES CHANGES HIGHLIGHTS 9 STANDARDIZED PIT SIZE IN THE HORIZONTAL JUMPS 2 2020 POINTS OF EMPHASIS 10 HOSTING A TRACK & FIELD MEET WITH COVID-19/ 4 EXPANDED SPRINT RELAY EXCHANGE ZONES SOCIAL DISTANCING 5 PROVIDING ASSISTANCE TO COMPETITORS DURING 14 THE JURY OF APPEALS – WHAT IT IS & HOW IT COMPETITION FUNCTIONS 6 ESTABLISHING TAKE-OFF MARKS IN THE 15 ELECTRONIC DISTANCE MEASURE (EDM) – BEST HORIZONTAL JUMPS, POLE VAULT AND JAVELIN PRACTICES 7 HOW TO CORRECTLY UTILIZE COURSE MARKINGS 17 CROSS COUNTRY TRAINING SAFETY TIPS FOR IN CROSS COUNTRY INDIVIDUALS & TEAMS 8 CROSS COUNTRY COURSE LAYOUT – THE BASICS 18 CORRECT PLACEMENT OF THE HURDLES 2020 POINTS OF EMPHASIS 1. Meet Administration Providing a quality experience to track and field athletes, coaches, and spectators does not happen by accident. Many months of pre-planning and execution have occurred before the event is finalized and the first event begins. -

The International Ski Competition Rules (Icr)

THE INTERNATIONAL SKI COMPETITION RULES (ICR) BOOK II CROSS-COUNTRY APPROVED BY THE 51ST INTERNATIONAL SKI CONGRESS, COSTA NAVARINO (GRE) EDITION MAY 2018 INTERNATIONAL SKI FEDERATION FEDERATION INTERNATIONALE DE SKI INTERNATIONALER SKI VERBAND Blochstrasse 2; CH- 3653 Oberhofen / Thunersee; Switzerland Telephone: +41 (33) 244 61 61 Fax: +41 (33) 244 61 71 Website: www.fis-ski.com ________________________________________________________________________ All rights reserved. Copyright: International Ski Federation FIS, Oberhofen, Switzerland, 2018. Oberhofen, May 2018 Table of Contents 1st Section 200 Joint Regulations for all Competitions ................................................... 3 201 Classification and Types of Competitions ................................................... 3 202 FIS Calendar .............................................................................................. 5 203 Licence to participate in FIS Races (FIS Licence) ...................................... 7 204 Qualification of Competitors ....................................................................... 8 205 Competitors Obligations and Rights ........................................................... 9 206 Advertising and Sponsorship .................................................................... 10 207 Competition Equipment and Commercial Markings .................................. 12 208 Exploitation of Electronic Media Rights .................................................... 13 209 Film Rights .............................................................................................. -

The Hammpions

2019 Relay Team Profile: The Hammpions For two brothers from a family that loves running, the opportunity has finally arrived to team up as a duo for a popular long-distance relay race. Later this month, John and Paul Crowe will run the 50 miles of the Tussey mOUnTaiNBACK 50 Mile Relay and Ultramarathon as a two-person relay team. Both grew up in State College. John Crowe now lives in Pittsburgh and Paul Crowe lives in Milford, NJ. “This is our first time doing the Mountainback,” said John Crowe. “Our dad has always been involved in some capacity, whether hosting runners or competing on teams, so it has always been on our radar.” It’s pretty well known in the local running community that Crowes are not the type to shrink from a challenge. Their father, Rob Crowe, has run numerous races over the years, including the Boston Marathon, and still actively races in the local community. Their mother, Sue, was a standout runner, including multiple wins at the Nittany Valley Arts Festival race. But this kind of race is often out of bounds for students who run for cross country or track teams. “Unfortunately we never had the opportunity to participate in it while we were in high school and college,” said John Crowe. “Now that we are both trying to get back into running competitively again, this seemed like the perfect race to do together.” The course’s 12 segments on the roads of Rothrock State Forest are of unequal length and difficulty, so when these two runners switch back and forth to run every other segment, one will run a total of about 22 and the other about 28 miles. -

A Parent's Guide to Cross-Country

A Parent's Guide to Cross-Country What is cross-country? Cross-country is a team running sport that takes place in the fall on a measured 5000 meter (3.1 miles) High School course or 2 mile course for the Jr. High over varied surfaces and terrain. Our home course is located in City Park on the levee near Troy Memorial Stadium and Hobart Arena. How is cross-country scored? A cross-country meet is scored by adding up the places of the top 5 finishers for each team. As in golf, the low score wins. For example, a team that scores 26 points places ahead of a team that scores 29 points, as follows: Troy Piqua 1 2 4 3 5 7 6 8 10 9 Totals: 26 pts 29pts Troy Wins A team's 6th and 7th finishers can also figure in the scoring if they place ahead of other teams' top 5 finishers. When that is the case, they become "pushers" by pushing up their opponents' scores, as follows: Troy Piqua 2 1 3 4 6 5 8 7 9 (10)(11) 12 Totals: 28 pts 29 pts Troy Wins Only a team's 6th and 7th finishers can be pushers, regardless of how many of its runners may finish ahead of an opposing team's top 5 finishers. This is also known as displacing another team's scoring runner(s). This is why the 6th and 7th runners are just as important as the top 5. What happens in case of a scoring tie? If a tie in scoring occurs, then the team who has their 6th runner in first wins. -

Maximal Time Spent at Vo2max from Sprint to the Marathon

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Maximal Time Spent at VO2max from Sprint to the Marathon Claire A. Molinari 1,2, Johnathan Edwards 3 and Véronique Billat 1,* 1 Unité de Biologie Intégrative des Adaptations à l’Exercice, Université Paris-Saclay, Univ Evry, 91000 Evry-Courcouronnes, France; [email protected] 2 BillaTraining SAS, 32 rue Paul Vaillant-Couturier, 94140 Alforville, France 3 Faculté des Sciences de la Motricité, Unité d’enseignement en Physiologie et Biomécanique du Mouvement, 1070 Bruxelles, Belgium; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +33-(0)-786117308 Received: 6 November 2020; Accepted: 8 December 2020; Published: 10 December 2020 Abstract: Until recently, it was thought that maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) was elicited only in middle-distance events and not the sprint or marathon distances. We tested the hypothesis that VO2max can be elicited in both the sprint and marathon distances and that the fraction of time spent at VO2max is not significantly different between distances. Methods: Seventy-eight well-trained males (mean [SD] age: 32 [13]; weight: 73 [9] kg; height: 1.80 [0.8] m) performed the University of Montreal Track Test using a portable respiratory gas sampling system to measure a baseline VO2max. Each participant ran one or two different distances (100 m, 200 m, 800 m, 1500 m, 3000 m, 10 km or marathon) in which they are specialists. Results: VO2max was elicited and sustained in all distances tested. The time limit (Tlim) at VO2max on a relative scale of the total time (Tlim at VO2max%Ttot) during the sprint, middle-distance, and 1500 m was not significantly different (p > 0.05).