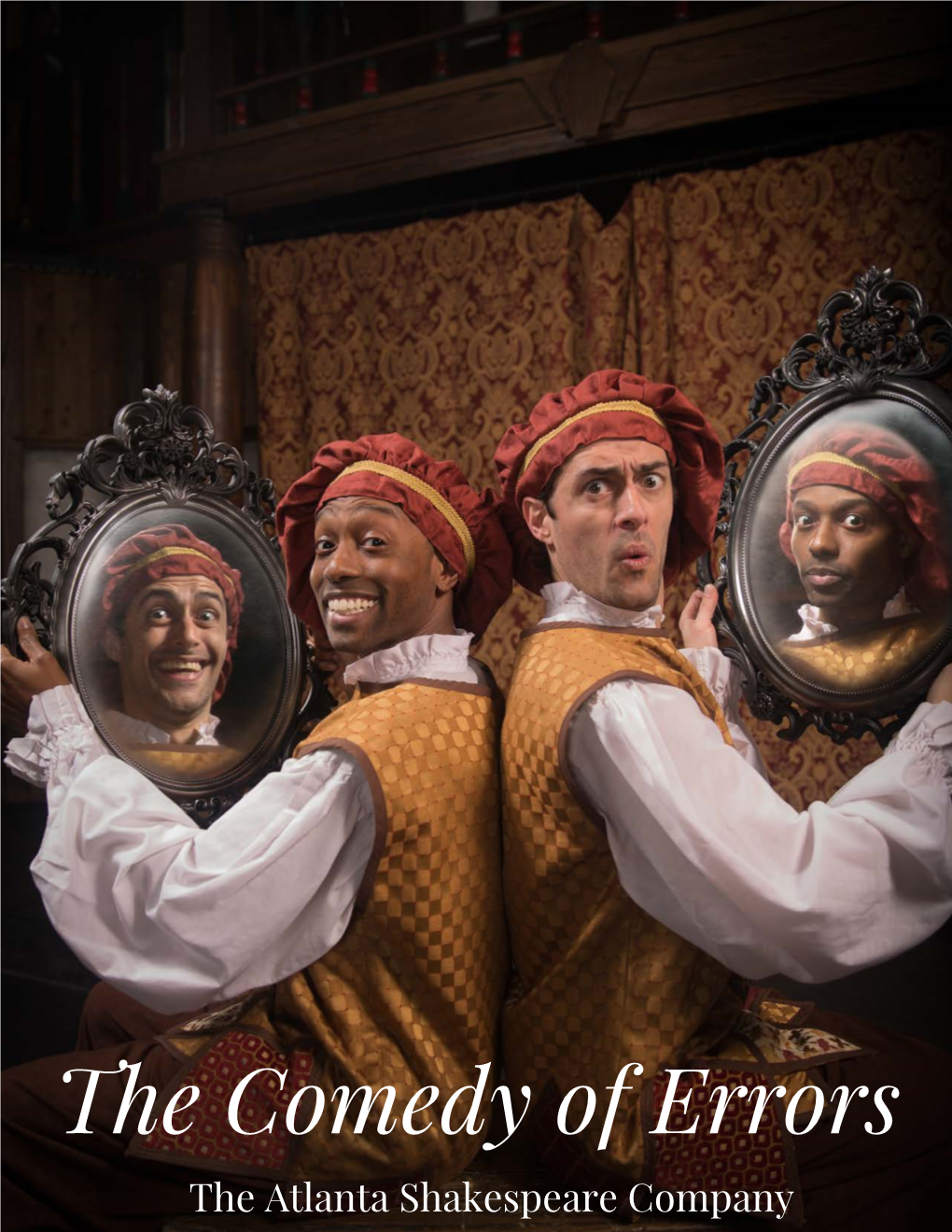

Comedy of Errors Study Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saving the World Through Iambic Pentameter... Atlanta Shakespeare Company Education Programs 2014-15 INSPIRED! Delighted!

Saving the world through iambic pentameter... Atlanta Shakespeare Company Education Programs 2014-15 INSPIRED! delighted! thrilled! Students at the Shakespeare Tavern Playhouse enjoying A Midsummer Night’s Dream matinee performance/ASC Our Performance Approach... ASC Education Programs The Atlanta Shakespeare Company is the only professional theater company in Inside this Issue... Georgia actively producing the classics throughout the entire academic year. Our down-to-earth Shakespeare performance style, known as ‘Original Practice,’ engages Why Original Practice? students in a manner consistent with the playwright’s original intent. We base our How to Reserve Tickets to a productions on Shakespeare’s First Folio of plays, published in 1623 by his fellow artists. Performance Original Practice at the Tavern ensures that students and teachers will: Mainstage Performance calendars Sit in the region’s only Elizabethan-style playhouse, inspired by New Programming: Shakespeare 4 Kids Shakespeare’s own Globe Theatre. S.L.A.W “Shakespeare, the Language that Watch productions featuring actors in Elizabethan period costumes. Shaped a World” Hear period music on live instruments and live actor-created sound effects. How to Book “Shakespeare on Location” Thrill to dynamic, dramatic sword fights. In-Class Playshops Participate in a living, breathing, and exciting theatrical experience, Design Your Own Residencies made more engaging by an active relationship between actor and More Ways to Explore Theatre audience Studying and watching Shakespeare in -

Raise the Curtain

JAN-FEB 2016 THEAtlanta OFFICIAL VISITORS GUIDE OF AtLANTA CoNVENTI ON &Now VISITORS BUREAU ATLANTA.NET RAISE THE CURTAIN THE NEW YEAR USHERS IN EXCITING NEW ADDITIONS TO SOME OF AtLANTA’S FAVORITE ATTRACTIONS INCLUDING THE WORLDS OF PUPPETRY MUSEUM AT CENTER FOR PUPPETRY ARTS. B ARGAIN BITES SEE PAGE 24 V ALENTINE’S DAY GIFT GUIDE SEE PAGE 32 SOP RTS CENTRAL SEE PAGE 36 ATLANTA’S MUST-SEA ATTRACTION. In 2015, Georgia Aquarium won the TripAdvisor Travelers’ Choice award as the #1 aquarium in the U.S. Don’t miss this amazing attraction while you’re here in Atlanta. For one low price, you’ll see all the exhibits and shows, and you’ll get a special discount when you book online. Plan your visit today at GeorgiaAquarium.org | 404.581.4000 | Georgia Aquarium is a not-for-profit organization, inspiring awareness and conservation of aquatic animals. F ATLANTA JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2016 O CONTENTS en’s museum DR D CHIL ENE OP E Y R NEWL THE 6 CALENDAR 36 SPORTS OF EVENTS SPORTS CENTRAL 14 Our hottest picks for Start the year with NASCAR, January and February’s basketball and more. what’S new events 38 ARC AROUND 11 INSIDER INFO THE PARK AT our Tips, conventions, discounts Centennial Olympic Park on tickets and visitor anchors a walkable ring of ATTRACTIONS information booth locations. some of the city’s best- It’s all here. known attractions. Think you’ve already seen most of the city’s top visitor 12 NEIGHBORHOODS 39 RESOURCE Explore our neighborhoods GUIDE venues? Update your bucket and find the perfect fit for Attractions, restaurants, list with these new and improved your interests, plus special venues, services and events in each ’hood. -

Euhm-Restaurant-Guide.Pdf

RESTAURANT GUIDE American 4th & Swift 621 North Ave NE 678.904.0160 Broadway Diner 620 Peachtree St NE 404.477.9600 Eats 600 Ponce De Leon Ave NE 404.888.9149 Erica's Fine Foods 134 Baker St NE 404.525.6240 Livingston Restaurant and Bar 659 Peachtree St NE 404.897.5000 The Lawrence 905 Juniper St NE 404.961.7177 The Spence 75 5th St NW 404.892.9111 Top Flr 674 Myrtle St NE 404.685.3110 Wing Nut 120 North Ave NE 678.702.9990 Woody's Famous Philadelphia Cheesesteaks 981 Monroe Dr NE 404.876.1939 Wing Stop 595 Piedmont Ave, STE 330 404-874-9464 Barbeque Fox Bros. Bar-B-Q 1238 DeKalb Ave NE 404.577.4030 Sweet Auburn Barbecue 209 Edgewood Ave SE 404.589.9722 The Pig and The Pearl 1380 Atlantic Ave NW 404.541.0930 Bars/Sports Bars Independent 931 Monroe Dr NE 404.249.9869 Midtown Tavern 554 Piedmont Ave NE 404.541.1372 Publik Draft House 654 Peachtree Street 404.885.7505 World of Beer 855 Peachtree St NE, STE 5 404.815.9221 Breakfast Dunkin' Donuts 225 Peachtree Street NE 404.223.6717 Flying Biscuit Café 1001 Piedmont Ave NE 404.874.8887 IHOP 428 Ponce de Leon Ave NE 404.228.2741 Krispy Kreme 295 Ponce De Leon Ave NE 404.876.7307 Livingston Restaurant + Bar 659 Peachtree Street NE 404.897.5000 Waffle House 66 5th St NW at Spring St NW 404.872.0028 Burgers Cypress Street Pint & Plate 817 W Peachtree St 404.815.9243 Fuze Burger 265 Ponce De Leon Ave NE 404.685.9988 The Varsity 61 North Ave NW 404.881.1706 Last Revised April 2016 1 Vortex Bar and Grill 878 Peachtree Street NE 404.875.1667 Grind house Grill 209 Edgewood Ave 404.522.3444 Chinese -

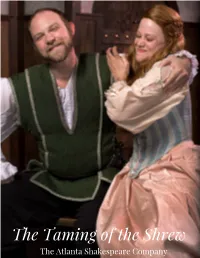

The Taming of the Shrew Study Guide

The Taming of the Shrew The Atlanta Shakespeare Company Staff Cast Artistic Director Jeff Watkins Director – Jeff WatkiNs Stage MaNager –CiNdy KearNs Director of Education and AssistaNt Stage MaNager – Lilly Baxley Training Laura Cole LightiNg DesigNer – Greg HanthorNe Development Director Rivka Levin Kate – Dani Herd Education Staff Kati Grace Brown, Tony Petruchio – Matt Nitchie Brown, Andrew Houchins, Adam King, Lucentio – Trey York Amanda Lindsey, Samantha Smith BiaNca, ServaNt – KristiN Storla TraNio – Adam KiNg Box Office Manager Becky Cormier Finch Hortensio – Paul Hester Baptista, ServaNt – Doug Kaye Art Manager Amee Vyas Grumio – Drew Reeves ViNcentio, ServaNt, Priest – Troy Willis Marketing Manager Jeanette Meierhofer Gremio, Tailor, ServaNt – J. ToNy BrowN BioNdello – Patrick Galletta Company Manager Joe Rossidivito Curtis, Haberdasher, Widow – Nathan Unless otherwise noted, photos Hesse appearing in this study guide are PedaNt – Clarke Weigle courtesy of Jeff Watkins. Study guide by Samantha Smith, Laura Cole, and Delaney Clark The Atlanta Shakespeare Company 499 Peachtree St NE Atlanta GA 30308 404-874-5299 www.shakespearetavern.com Like the Atlanta Shakespeare Company on Facebook and follow ASC on Twitter at @shakespearetav. Photo Credit: NatioNal Portrait Gallery WILLIAM 2016 was the four huNdredth aNNiversary of SHAKESPEARE Shakespeare's death, aNd celebratioNs hoNoriNg Shakespeare's plays were popular with Shakespeare (1564-1616) wrote thirty- Shakespeare's coNtributioN seveN plays, which have become staples all types of people, iNcludiNg the two to literature took place of classrooms aNd theatre performaNces moNarchs who ruled ENglaNd duriNg his arouNd the world. across the world. lifetime: Elizabeth I (1533-1603) aNd James I (1566-1625). The soN of a glove-maker, Shakespeare was borN iN Stratford-upoN-AvoN, Shakespeare fouNd both artistic aNd co- where he received a stroNg educatioN iN mmercial success through his writiNg. -

Tackling Challenging Issues in Shakespeare for Young Audiences

Shrews, Moneylenders, Soldiers, and Moors: Tackling Challenging Issues in Shakespeare for Young Audiences DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Elizabeth Harelik, M.A. Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Professor Lesley Ferris, Adviser Professor Jennifer Schlueter Professor Shilarna Stokes Professor Robin Post Copyright by Elizabeth Harelik 2016 Abstract Shakespeare’s plays are often a staple of the secondary school curriculum, and, more and more, theatre artists and educators are introducing young people to his works through performance. While these performances offer an engaging way for students to access these complex texts, they also often bring up topics and themes that might be challenging to discuss with young people. To give just a few examples, The Taming of the Shrew contains blatant sexism and gender violence; The Merchant of Venice features a multitude of anti-Semitic slurs; Othello shows characters displaying overtly racist attitudes towards its title character; and Henry V has several scenes of wartime violence. These themes are important, timely, and crucial to discuss with young people, but how can directors, actors, and teachers use Shakespeare’s work as a springboard to begin these conversations? In this research project, I explore twenty-first century productions of the four plays mentioned above. All of the productions studied were done in the United States by professional or university companies, either for young audiences or with young people as performers. I look at the various ways that practitioners have adapted these plays, from abridgments that retain basic plot points but reduce running time, to versions incorporating significant audience participation, to reimaginings created by or with student performers. -

(ASTR) and Theatre Library Association (TLA) 2017 Conference

Welcome to the American Society for Theatre Research (ASTR) and Theatre Library Association (TLA) 2017 Conference Extra/Ordinary Bodies: Interrogating the Performance and Aesthetics of “Difference” ASTR Graduate Student Caucus (GSC) Conference Assistance Packet 1 Conference Assistance Packet Table of Contents: The Conference Assistance Committee of the ASTR Graduate Student Caucus (GSC) is delighted to welcome you to ASTR 2017, Extra/Ordinary Bodies. We have provided this packet to help guide you through the conference, as well as the host city of Atlanta, GA. Here you will find information on the role of the GSC and how you can maximize your involvement with the GSC, as well as conference advice and support and information on food and drink, travel, and attractions in Atlanta. We hope you find this useful and look forward to meeting you all personally at the GSC events. 1. President’s Welcome Letter .2 ……………………………………………… 2. About the GSC ...3 ………………………………………………………………… 3. Meet the Team .............4 ……………………………………………………… -

AUTHENTIC ATLANTA ITINERARY Atlanta’S Peachtree Corridor Is Packed with Can’T-Miss Classics

AUTHENTIC ATLANTA ITINERARY Atlanta’s Peachtree Corridor is packed with can’t-miss classics. Whether you’ve got a few hours or a few days, use these tips and treks to create an authentic Atlanta experience! Centennial Olympic Park DAY 1 — DOWNTOWN grab a complimentary glass bottle of clas- sic formula Coca-Cola. Inside CNN Studio Tour Just across the street, Imagine It! The Children’s Museum of Atlanta MorninG features hands-on exhibits and activities where kids ages 8 and younger can learn Start your morning off with a splash! and explore. Whether it’s building a Georgia Aquarium – the world’s largest sandcastle, painting on the walls or aquarium – is an underwater wonderland, exploring the latest special exhibit, home to more than 100,000 creatures children will discover why it’s a smart from 500 species. Swimming, diving and place to play. Courtesy of Target Free lurking among the 10 million gallons of Second Tuesdays, all visitors can enjoy water, you’ll find dolphins, penguins, free admission from 1 p.m. until closing Hard Rock Cafe Atlanta beluga whales, sea otters, piranhas and on the second Tuesday of each month. so much more. Other wow-worthy the world’s largest Fountain of Rings. Enjoy year-round, family-friendly activities include AT&T Dolphin Tales, The Park also offers seasonal activities entertainment in Centennial Olympic Deepo’s Undersea 3D Wondershow, and such as Fourth Saturday Family Fun Days, Park. Right in the heart of downtown, the behind-the-scenes tours and lectures. free concerts April-September during home of the 1996 Olympic Games offers Next door, learn all about the world’s Wednesday WindDown and Music at concerts, festivals, seasonal activities and most beloved beverage at World of Noon every Tuesday and Thursday. -

Fulton County Cultural Summary

Fulton County cultural summary Regional Arts and Culture Forums Research Initiative The development of ARC’s Fifty Forward Plan and Plan 2040 places emphasis on the value of arts & culture to the region. It includes a call for “systematic annual data collection and analysis regarding the development of the creative economy in Georgia” and the development of a The Creative Industries in 2011 regional cultural master plan. Fulton County, GA Fulton County Summary This Creative Industries report offers a research-based approach to understanding the scope and economic importance of the arts in Fulton County, GA. The creative industries are composed of arts Few precedents exist of comprehensivebusinesses regional that range cooperationfrom non-profit museums, to symphonies,foster arts and theaters and to culture. for-profit film, Toarchitecture, that and advertising companies. Arts businesses and the creative people they employ stimulate innovation in end, the Atlanta Regional Commissiontodays contracted global marketplace. with the Metro Atlanta Arts & Culture Coalition from July to December of 2011 to conductNationally, the there areresearch 756,007 businesses contained in the U.S. in involved this in thedocument. creation or distribution The of following the arts. They employ 2.99 million people, representing 4.14 percent of all businesses and 2.17 percent of all information is a summary of the data employees,collected respectively. on Fulton The source County. for these data is Dun & Bradstreet, the most comprehensive and trusted source for business information in the U.S. For additional information on Fulton AsCounty of January and 2011, Fultonthe restCounty, of GA the is home 10 to Metro 4,965 arts-related Atlanta businesses counties that employ see the 29,817 people. -

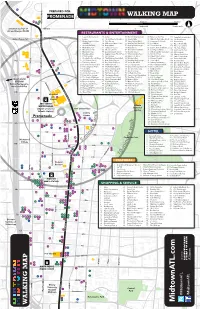

Midtowna TL.Com

P e a c h t re 17 e St PREPARED FOR: re et WALKING MAP PROMENADE 16 17 68 158 0 1/4 mile 1/2 mile 18 157 Peachtree West 67 5 min. walk 10 min. walk ° Beverly Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) 1 0 RESTAURANTS & ENTERTAINMENT - 15 M I 1 Legends Restaurant & 26 Arby’s 53 Fresh 2 Order (Salads) 80 Blake’s on the Park 122 Pasta Da Pulcinella (Ital.) N Peachtree Circle Buford Connector U Lounge 27 The Melting Pot (Fondue) 54 Vinny’s Pizza 81 Gilbert’s Cafe & Bar (Med.) 123 The Nook Tavern T E 2 Gladys Knight’s Chicken 28 Cafe Kia-ora 55 Senor Patron (Mex.) 82 Campagnolo (Italian) 124 Coffee Shop W & Waffles 29 Fifth Ivory Public House 56 MidCity Cafe (Bar/Viet.) 83 Ten (Amer.) 125 Opera Night Club A 3 Aloha Asian Bistro 30 Babs (Amer.) 57 Rooftop 866 Lounge 84 Zocalo Mexican L 126 Tin Lizzy’s Cantina K 4 Midtown Tavern 31 TaKorea (Korean) 58 Briza (Amer.) 85 Empire State South (Amer.) 127 Flip Flops (Pizza) 5 The Grille at 590 32 Mu Lan Chinese 59 The Lawrence (Amer.) 86 Cafe Agora (Med.) 128 South City Kitchen 6 Mandarin Palace 33 Escorpion (Latin Amer.) 60 Noodle (Asian) 87 Arden’s Garden (Juice Bar) 129 Sutra Lounge 7 Broadway Diner 34 Cypress Street Pint & Plate 61 Villains (Sandwiches) 88 Domino’s Pizza 14 130 Subway Sandwiches 8 Pita’s Republic 35 Halo Lounge 62 Lime Fresh (Mex.) 89 Primal Atlanta (Club) 131 Park 75 (American) 9 Goodfella’s Pizza & Wings 36 The Biltmore Cafe & Grill 63 Bulldog’s (Bar) 90 Chinese Buddha 132 Starbucks Coffee 18th 10 J.R. -

Best Unofficial Guide to Life at Emory (BUGLE)

THE DEPARTMENT OF MEDICINE’S NEW FACULTY “BUGLE”: The “Best Unofficial Guide to Life at Emory” 2020-2021 EMORY UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MEDICINE DEPARTMENT OF MEDICINE Disclaimer: Please note that this is an unofficial guide to life at Emory and in no way reflects the view or opinions of Emory University, its parent company, affiliates or contractors. CREATED BY: Sushma K. Cribbs, MD, MSc APPLICATION DEVELOPMENT: Christopher Knudson, MD EDITED BY: Members of the Faculty Development Committee REVISED 2/1/2021 2 Dear Colleague, Welcome to Emory! Whether you’ve just set foot in Atlanta or you’re an Emory “lifer,” we hope the New Faculty BUGLE is a helpful resource. This guide, developed by the Emory Department of Medicine’s Early Career Faculty Development Subcommittee, is designed to address questions about subjects ranging from grant support to Emory discounts at Six Flags to the location of the Grady parking office—and everything in between. Many sections are self-contained, but others will direct you to a link with the information you need. As BUGLE is a work in progress, we would greatly appreciate any feedback or corrections. Edits, questions, and comments can be sent to [email protected]. More information about Faculty Development can be found on our website. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. General information about the DOM II. Hospital-specific information a. Emory University Hospital (EUH) b. Emory University Hospital Midtown (EUHM) 3 c. Grady Memorial Hospital (GMH) d. Atlanta VA Medical Center (VAMC) e. Emory St. Joseph’s Hospital (ESJH) III. COVID-19 Information (e.g. PPE, what to do if you become ill, research studies) a. -

By: William Shakespeare Adapted & Directed By: Carrie

ANNISTON PERFORMING ARTS CENTER THE CALHOUN COUNTY CHAMBER OF COMMERCE FOUNDATION & JACKSONVILLE STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF ARTS & HUMANITIES PRESENT THE SHAKESPEARE PROJECT’s BY: WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE ADAPTED & DIRECTED BY: CARRIE COLTON AUGUST 14-18, 2019 CAST MACBETH .................................................................... MATTHEW MURRY MACDUFF..................................................................ANATASHA BLAKELY LADY MACBETH .....................................................STEPHANIE ESCORZA BANQUO .......................................................................... KARL HAWKINS QUEEN DUNCAN ....................................................... STEPHANIE MURRY WEIRD JESTER/PORTER.................................................. JACOB SORLING WEIRD JESTER/DOCTOR ................................................. LIZZIE POWERS WEIRD JESTER/LORD......................................................LEILA ACHESON* ROSS .......................................................... NARDGELEN JEAN FRANCOIS LENNOX.......................................................................... KENNEDY JONES MALCOLM .......................................................................... SEAN GOLSON LORD MACDUFF..................................................................DYLAN HURST SEYTON...................................................................... AVERY GALLAHAR* SIWARD ............................................................................. EMILY TAYLOR FLEANCE/YOUNG SOLDIER.......................................... -

DOWNTOWN News for Central Atlanta Progress Members and Downtown Property Owners

FALL 2010 WHAT’S UP DOWNTOWN News for Central Atlanta Progress members and Downtown property owners. Atlanta Streets Alive in Woodruff Park Returning in October. See Page 12. Fall 2010 n E W S Georgia Forward Forum Internship Program Explores Georgia’s Future Honors Paul Kelman n Aug. 25, Georgia’s academic, civic, economic, n honor of Paul B. Kelman’s 22 years of leadership at Central Atlanta and government leaders began a long-awaited Progress, the organization has renamed the existing internship program the Kelman Internship Program. During Kelman’s tenure, major changes conversation about the future of our state. The occurred in the landscape of Downtown Atlanta. Most notable is the Macon State College Conference Center played creation of ADID in 1995, which funds the Ambassador Force, a highly visible Ohost to the 2010 Georgia Forward Forum. More than 200 authoritative presence on Downtown. stakeholders, representing every corner of the state, convened A Florida native, Kelman received his civil engineering degree from Georgia to discuss the most pressing challenges facing Georgians Tech and masters degrees from the University of Illinois (in urban planning) today, including the economy, water equity, education, and and Georgia State University (in public administration). He received the transportation. Owens-Illinois Scholarship at Georgia Tech and the Richard King Mellon Fellowship at the University of Illinois. Kelman is past president of the Georgia Following the theme “Together, improving Planning Association and a charter member of the American Planning the state of our state,” the day-long forum Association. In April 2003, he received the first Jack F.