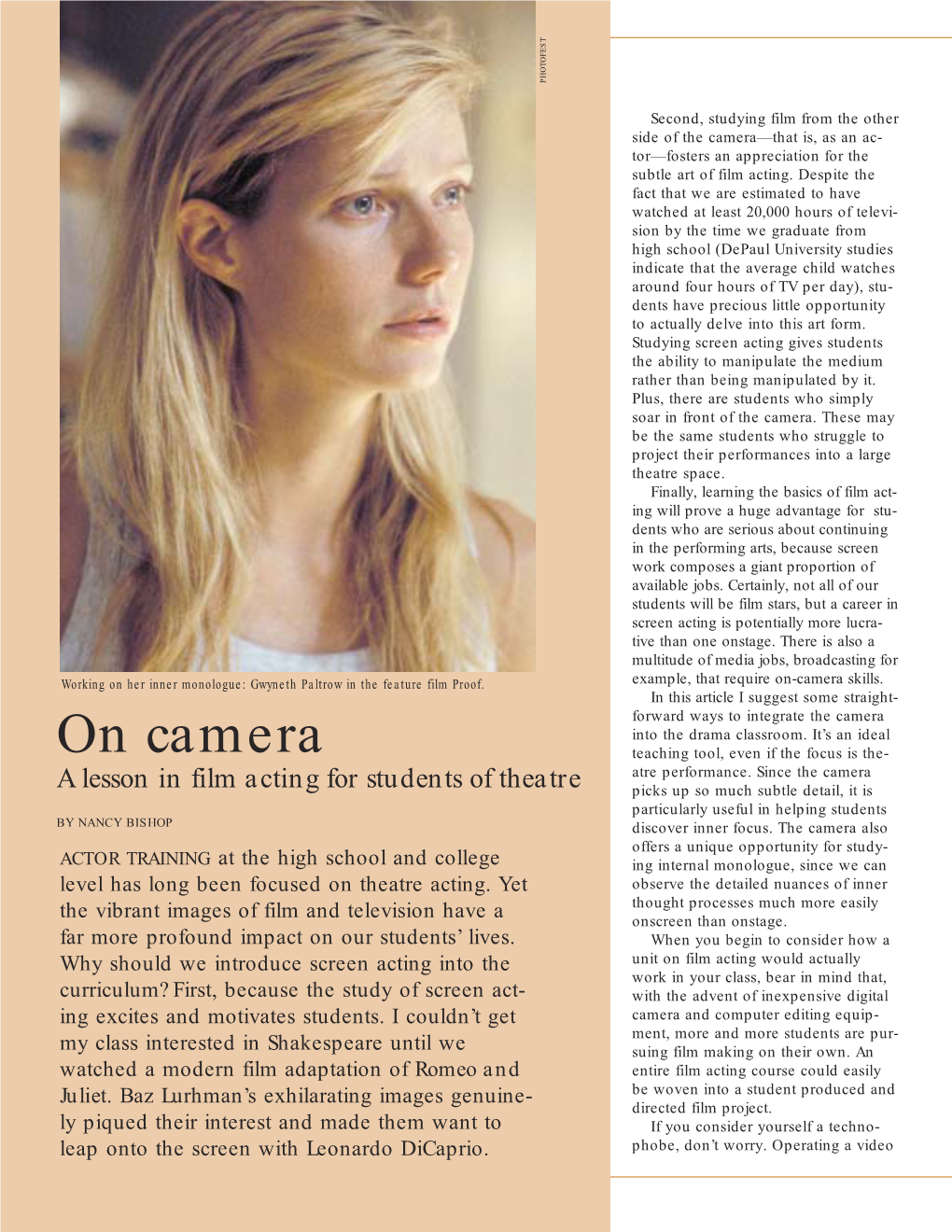

On Camera Teaching Tool, Even If the Focus Is The- Atre Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glengarry Glen Ross Free

FREE GLENGARRY GLEN ROSS PDF David Mamet | 144 pages | 26 Aug 2004 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9780413774187 | English | London, United Kingdom Glengarry Glen Ross movie review () | Roger Ebert When an office full of New York City real estate salesmen is given the news that all but the top two will be fired at the end of the week, the atmosphere begins to heat up. Shelley Levene, who has a sick daughter, does everything in his Glengarry Glen Ross to get better leads from his boss, John Williamson, but to no avail. When his coworker Dave Moss comes up with a plan to steal the leads, things get complicated for the tough-talking Glengarry Glen Ross. Joseph M. Caracciolo Jr. Jerry Tokofsky Stanley R. William Barclay Bob Shaw. Five minutes into the picture and there's so much awesomeness on the screen that it's almost overwhelming. Second time through and just as enjoyable as the first. First-rate cast, first-rate dialogue. Feels like a modernized Glengarry Glen Ross of a Salesman, with matching commentary on working class life "we work too hard"on shifting power structures the young managing the oldand on the emotional economics of capitalism subjection vs satisfaction. I didn't remember the characters being so consistently foul-mouthed, and this time through was slightly distracted by the film's heavy reliance on vulgarity. Nonetheless, this is an absolutely captivating film recommended to anyone who loves great actors, great characters, or great dialogue. It's amazing how a film focused exclusively on people talking can be so engrossing. -

The Face of an Angel Synopsis

THE FACE OF AN ANGEL SYNOPSIS The brutal murder of a Bri1sh student in Tuscany leads to the trial and convic1on of her American flatmate and Italian boyfriend in controversial circumstances. The media feeding frenzy around the case aracts once successful, but now struggling filmmaker Thomas, to be commissioned to write a film - 'The Face of an Angel', based on a book by Simone Ford an American journalist who covered the case. From Rome they head to Siena to research the film. Thomas has recently separated from his wife in a bi=er divorce and leI his 9-year-old daughter in Los Angeles. This unravelling of his own life, and the dark mediaeval atmosphere surrounding the case, begins to drag him down into his own personal hell. Like Dante journeying through the Inferno in the Divine Comedy, with Simone as his guide to the tragedy of the murder, Thomas starts a relaonship with a student Melanie. This is a beau1ful, unrequited love, where she acts as a guide to his own heart. He comes to realise the most important thing in his life is not solving an unsolvable crime, or wri1ng the film, but returning to the daughter he has leI behind. | THE FACE OF AN ANGEL | 1 SHEET | 15.10.2013 | 1!5 THE FACE OF AN ANGEL CAST DANIEL BRÜHL KATE BECKINSALE In 2003 Daniel Brühl took the leading role in the box office smash Good English actress Kate Beckinsale is revealing herself to be one of films’ Bye Lenin!, which became one of Germany’s biggest box office hits of all most versale and charismac actresses. -

Robert De Niro's Raging Bull

003.TAIT_20.1_TAIT 11-05-12 9:17 AM Page 20 R. COLIN TAIT ROBERT DE NIRO’S RAGING BULL: THE HISTORY OF A PERFORMANCE AND A PERFORMANCE OF HISTORY Résumé: Cet article fait une utilisation des archives de Robert De Niro, récemment acquises par le Harry Ransom Center, pour fournir une analyse théorique et histo- rique de la contribution singulière de l’acteur au film Raging Bull (Martin Scorcese, 1980). En utilisant les notes considérables de De Niro, cet article désire montrer que le travail de cheminement du comédien s’est étendu de la pré à la postproduction, ce qui est particulièrement bien démontré par la contribution significative mais non mentionnée au générique, de l’acteur au scénario. La performance de De Niro brouille les frontières des classes de l’auteur, de la « star » et du travail de collabo- ration et permet de faire un portrait plus nuancé du travail de réalisation d’un film. Cet article dresse le catalogue du processus, durant près de six ans, entrepris par le comédien pour jouer le rôle du boxeur Jacke LaMotta : De la phase d’écriture du scénario à sa victoire aux Oscars, en passant par l’entrainement d’un an à la boxe et par la prise de soixante livres. Enfin, en se fondant sur des données concrètes qui sont restées jusqu’à maintenant inaccessibles, en raison de la modestie et du désir du comédien de conserver sa vie privée, cet article apporte une nouvelle perspective pour considérer la contribution importante de De Niro à l’histoire américaine du jeu d’acteur. -

Al Pacino Receives Bfi Fellowship

AL PACINO RECEIVES BFI FELLOWSHIP LONDON – 22:30, Wednesday 24 September 2014: Leading lights from the worlds of film, theatre and television gathered at the Corinthia Hotel London this evening to see legendary actor and director, Al Pacino receive a BFI Fellowship – the highest accolade the UK’s lead organisation for film can award. One of the world’s most popular and iconic stars of stage and screen, Pacino receives a BFI Fellowship in recognition of his outstanding achievement in film. The presentation was made this evening during an exclusive dinner hosted by BFI Chair, Greg Dyke and BFI CEO, Amanda Nevill, sponsored by Corinthia Hotel London and supported by Moët & Chandon, the official champagne partner of the Al Pacino BFI Fellowship Award Dinner. Speaking during the presentation, Al Pacino said: “This is such a great honour... the BFI is a wonderful thing, how it keeps films alive… it’s an honour to be here and receive this. I’m overwhelmed – people I’ve adored have received this award. I appreciate this so much, thank you.” BFI Chair, Greg Dyke said: “A true icon, Al Pacino is one of the greatest actors the world has ever seen, and a visionary director of stage and screen. His extraordinary body of work has made him one of the most recognisable and best-loved stars of the big screen, whose films enthral and delight audiences across the globe. We are thrilled to honour such a legend of cinema, and we thank the Corinthia Hotel London and Moët & Chandon for supporting this very special occasion.” Alongside BFI Chair Greg Dyke and BFI CEO Amanda Nevill, the Corinthia’s magnificent Ballroom was packed with talent from the worlds of film, theatre and television for Al Pacino’s BFI Fellowship presentation. -

A Pinewood Dialogue with Kenneth Branagh and Michael Caine

TRANSCRIPT A PINEWOOD DIALOGUE WITH KENNETH BRANAGH AND MICHAEL CAINE The prolific and legendary actor Michael Caine starred in both the 2007 film version of Sleuth (opposite Jude Law) and the 1972 version (opposite Laurence Olivier). In the new version, an actors’ tour de force directed by Kenneth Branagh and adapted by playwright Harold Pinter, Caine took the role originally played by Olivier. A riveting tale of deception and deadly games, this thriller about an aging crime novelist and a young actor in love with the same woman is essentially about the mysteries of acting and writing. In this discussion, Branagh and Caine discussed their collaboration after a special preview screening. A Pinewood Dialogue following a screening BRANAGH: Rubbish, of course. Rubbish. of Sleuth, moderated by Chief Curator David Schwartz (October 3, 2007): SCHWARTZ: Well, we’ll see, we’ll see. Tell us about how this project came about. It’s an interesting MICHAEL CAINE: (Applause) pedigree, because in a way, it’s a new version, an Good evening. adaptation, of a play. It seems like it’s going to be a remake of the film, but Harold Pinter, of course, KENNETH BRANAGH: Good evening. is the author here. DAVID SCHWARTZ: Welcome and congratulations BRANAGH: As you may have seen from the credits, on a riveting, very entertaining movie. one of the producers is Jude Law. He was the one who had the idea of making a new version, BRANAGH: Thank you. and it was his idea to bring onboard a man he thought he’d never get to do it, but Nobel Prize- CAINE: Thank you. -

OSLO Casting Announcement

MICHAEL ARONOV, ADAM DANNHEISSER, JENNIFER EHLE, DANIEL JENKINS, DARIUSH KASHANI, JEFFERSON MAYS, DANIEL ORESKES, HENNY RUSSELL, JOSEPH SIRAVO, T. RYDER SMITH TO BE FEATURED IN THE LINCOLN CENTER THEATER PRODUCTION OF “OSLO” a new play by J.T. ROGERS directed by BARTLETT SHER PREVIEWS BEGIN THURSDAY, JUNE 16 OPENING NIGHT IS MONDAY, JULY 11 AT THE MITZI E. NEWHOUSE THEATER Lincoln Center Theater (under the direction of André Bishop) has announced that Michael Aronov, Adam Dannheisser, Jennifer Ehle, Daniel Jenkins, Dariush Kashani, Jefferson Mays, Daniel Oreskes, Henny Russell, Joseph Siravo, and T. Ryder Smith will be featured in the cast of its upcoming production of OSLO, a new play by J.T. Rogers, directed by Bartlett Sher. Commissioned by Lincoln Center Theater, OSLO begins performances Thursday, June 16 and will open Monday, July 11 at the Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater (150 West 65 Street). Additional casting will be announced at a later date. It’s 1993. The world watches the impossible: Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Palestinian Liberation Organization Chairman Yasser Arafat, standing together in the White House Rose Garden, signing the first ever peace agreement between Israel and the PLO. How were the negotiations kept secret? Why were they held in a castle in the middle of Norway? And who are these mysterious negotiators? A darkly comic epic, OSLO tells the true, but until now, untold story of how one young couple, Norwegian diplomat Mona Juul (to be played by Jennifer Ehle) and her husband social scientist Terje Rød-Larsen (to be played by Jefferson Mays), planned and orchestrated top-secret, high-level meetings between the State of Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization, which culminated in the signing of the historic 1993 Oslo Accords. -

Shakespeare on Film- Looking for Richard

SHAKESPEAREONFILM LOOKING FOR RICHARD Teachers’ Notes This study guide is aimed at students of GCSE English and Media, A’ level English Media and Film and GNVQ Media: Communication and Production. Areas investigated include Filming Shakespeare, Language, Documentary Styles and Representation. This series of study guides aims to provide teachers with valuableresource materials for the teaching of Shakespeare throughout the National Curriculum. Synopsis The American actor Al Pacino is the co-producer, director and star of the film ‘Looking For Richard’. His project intertwines the telling of the story of Shakespeare’s ‘Richard III’ with an intimate look at the actors’ and filmmakers’ processes as they come to grips with their characterisations and with translating their enthusiasm for the play onto film. The film ‘Looking For Richard’ follows their debates and revelations about the play, takes to the streets of New York to measure public opinion, visits the birthplace of Shakespeare and, finally, looks at a production of Richard III’. The film includes interviews with actors such as Kenneth Branagh and Vanessa Redgrave and seeks to prove that everyone can enjoy Shakespeare, and that his tales are timeless and universal. The completion of the film marks the culmination of a journey begun decades ago. when Pacino was touring colleges in the late 70’s talking to students who were reluctant to listen to Shakespeare and couldn’t see the relevance of his works. “But we would talk informally about the play and then I would read an excerpt” explains Pacino. Pacino notes, “By juxtaposing the day-to-day life of the actors and their characters with ordinary people, we attempted to create a comic mosaic - a very different Shakespeare. -

“Great Lives” Biography Book Group Brookfield Public Library 2021-22 Books Are Available at the Circulation Desk About a Month Before the Meeting

April 2021-revised “Great Lives” Biography Book Group Brookfield Public Library 2021-22 Books are available at the Circulation Desk about a month before the meeting. Anyone interested in reading and discussing biographies is welcome! Please check the sign in the lobby for the location of the meeting each month. Monday, June 28, 2021 1:00pm Rocket Men by Robert Kurson In early 1968, the Apollo program was on shaky footing. President Kennedy's end-of-decade deadline to put a man on the Moon was in jeopardy, and the Soviets were threatening to pull ahead in the space race. By August 1968, with its back against the wall, NASA decided to scrap its usual methodical approach and shoot for the heavens. With a focus on astronauts Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, and Bill Anders, and their wives and children, this is a vivid, gripping, you-are-there narrative that shows anew the epic danger involved, and the singular bravery it took, for man to leave Earth for the first time--and to arrive at a new world. (Polaris summary) Monday, July 26, 2021 1:00pm Code Name: Lise by Larry Loftis The year is 1942, and World War II is in full swing. Odette Sansom decides to follow in her war hero father's footsteps by becoming an SOE agent to aid Britain and her beloved homeland, France. Five failed attempts and one plane crash later, she finally lands in occupied France to begin her mission. It is here that she meets her commanding officer Captain Peter Churchill. As they successfully complete mission after mission, Peter and Odette fall in love. -

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5030

k. ARTS & VARIETY a~ Esther Jandrich Senior Exhibit "Relentless Germination" By Andrew Toelie Concordia Senior Esther Rose Jandrich will be presenting her That's what I'm hoping people will gain after touring this exhibition." first public art show to the CSP community on April 6th, 2015. Esther's senior art show "Relentless Germination" will be up in Esther's show, "Relentless Germination" is a sculpture exhibition which the H. Williams Teaching Gallery from April 6th to the 17th. Guests reflects a selection of emotional events being transformed into visual can see this collection Monday-Friday from 10:00 AM to 4:00 PM. objects. "My show is a capstone of my life so far. This exhibition Her closing reception will be the day after the Student Juried Show, includes a majority of things that 1 have learned since I became an taking place from 5:00 to 7:00 PM. The event is free and refreshments artist at Concordia. This show has also will be provided. While touring the exhibition, helped me reflect on how much I have Esther will have a guest book available for grown, both as a person and as a sculptor." visitors, giving them a chance to write Inside the show, there will be feedback about Esther's work and supporting four sculptured portraits. Each sculpture ^ her art career. This will give Esther more chronologically tells a story about a opportunities to learn new things, present her significant time in Esther's life. Each work to larger audiences, and continue to grow sculpture also reflects a variety of a positive reputation as a God blessed talent. -

Films with 2 Or More Persons Nominated in the Same Acting Category

FILMS WITH 2 OR MORE PERSONS NOMINATED IN THE SAME ACTING CATEGORY * Denotes winner [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] 3 NOMINATIONS in same acting category 1935 (8th) ACTOR -- Clark Gable, Charles Laughton, Franchot Tone; Mutiny on the Bounty 1954 (27th) SUP. ACTOR -- Lee J. Cobb, Karl Malden, Rod Steiger; On the Waterfront 1963 (36th) SUP. ACTRESS -- Diane Cilento, Dame Edith Evans, Joyce Redman; Tom Jones 1972 (45th) SUP. ACTOR -- James Caan, Robert Duvall, Al Pacino; The Godfather 1974 (47th) SUP. ACTOR -- *Robert De Niro, Michael V. Gazzo, Lee Strasberg; The Godfather Part II 2 NOMINATIONS in same acting category 1939 (12th) SUP. ACTOR -- Harry Carey, Claude Rains; Mr. Smith Goes to Washington SUP. ACTRESS -- Olivia de Havilland, *Hattie McDaniel; Gone with the Wind 1941 (14th) SUP. ACTRESS -- Patricia Collinge, Teresa Wright; The Little Foxes 1942 (15th) SUP. ACTRESS -- Dame May Whitty, *Teresa Wright; Mrs. Miniver 1943 (16th) SUP. ACTRESS -- Gladys Cooper, Anne Revere; The Song of Bernadette 1944 (17th) ACTOR -- *Bing Crosby, Barry Fitzgerald; Going My Way 1945 (18th) SUP. ACTRESS -- Eve Arden, Ann Blyth; Mildred Pierce 1947 (20th) SUP. ACTRESS -- *Celeste Holm, Anne Revere; Gentleman's Agreement 1948 (21st) SUP. ACTRESS -- Barbara Bel Geddes, Ellen Corby; I Remember Mama 1949 (22nd) SUP. ACTRESS -- Ethel Barrymore, Ethel Waters; Pinky SUP. ACTRESS -- Celeste Holm, Elsa Lanchester; Come to the Stable 1950 (23rd) ACTRESS -- Anne Baxter, Bette Davis; All about Eve SUP. ACTRESS -- Celeste Holm, Thelma Ritter; All about Eve 1951 (24th) SUP. ACTOR -- Leo Genn, Peter Ustinov; Quo Vadis 1953 (26th) ACTOR -- Montgomery Clift, Burt Lancaster; From Here to Eternity SUP. -

New Years Eve Films

Movies to Watch on New Year's Eve Going Out Is So Overrated! This year, New Year’s Eve celebrations will have to be done slightly differently due to the pandemic. So, the Learning Curve thought ‘Why not just ring in 2021 with some feel-good movies in your comfy PJs instead?’ After all, everyone knows that the best way to turn over a new year is snuggled up in front of the TV with a hot beverage in your hand. The good news is, no matter how you want to feel going into the next year, there’s a movie on this list that’ll deliver. Best of all — you won’t wake up the next day and begin January with a hangover! Godfather Part II (1974) Director: Francis Ford Coppola Starring: Al Pacino, Robert De Niro, Robert Duvall Continuing the saga of the Corleone crime family, the son, Michael (Pacino) is trying to expand the business to Las Vegas, Hollywood and Cuba. They delve into double crossing, greed and murder as they all try to be the most powerful crime family of all time. Godfather part II is hailed by fans as a masterpiece, a great continuation to the story and the best gangster movie of all time. This is a character driven movie, as we see peoples’ motivations, becoming laser focused on what they want and what they will do to get it. Although the movie is a gripping slow crime drama, it does have one flaw, and that is the length of the movie clocking in at 3 hours and 22 minutes. -

August 2014 Millbrae Life & Times

August 2014 Millbrae Life & Times MILLBRAE HISTORICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER Historical Spotlight: Notable Millbraeans By Tom Dawdy INSIDE THIS I S S U E : Historical Spotlight 1 President’s Report 1 Vice-President’s Message 3 Comic Strip 3 Curator’s Report 5 MHS Field Trip Info 5 There have been a lot of notable people that have come out of our small town of Train Museum News 5 Millbrae. Every time I discuss this subject with my friends and neighbors, I hear of more people to add to my list. I have picked out a handful of these “Notable Millbraeans” that have achieved fame on a national and international platform. Calendar of Events 6 (continued on Page 4) President’s Report John Muniz Friends and fellow members, make our picnic a successful event. For at least twenty-five years, the I want to give a big “thank you” to Millbrae Lions Club has been all who attended our annual cooking for our picnic - thank you so Fourth of July Picnic . It is always much Millbrae Lions. Also, thanks to big crowd and lots of hungry bar- great to see our friends and mem- the Millbrae Leo’s Club for serving gain hunters. We had tons of bers who every year celebrate our and cleaning up for us for the past gently-used items to suit every- nation’s birthday with the Millbrae seven years. Historical Society. We are very one’s taste. Assistant Curator fortunate to have two fantastic Our annual Rummage Sale was Dorothy Semke always does a Millbrae-based community service held on Saturday, August 9 in front fantastic job organizing, pricing organizations that step up and of the Millbrae Museum.