Mindfulness and Self-Efficacy in Pain Perception, Stress and Academic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heart of Norway

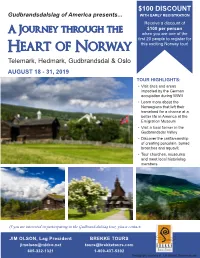

$100 DISCOUNT Gudbrandsdalslag of America presents... WITH EARLY REGISTRATION Receive a discount of $100 per person A Journey through the when you are one of the first 20 people to register for Heart of Norway this exciting Norway tour! Telemark, Hedmark, Gudbrandsdal & Oslo AUGUST 18 - 31, 2019 TOUR HIGHLIGHTS: • Visit sites and areas impacted by the German occupation during WWII • Learn more about the Norwegians that left their homeland for a chance at a better life in America at the Emigration Museum • Visit a local farmer in the Gudbrandsdal Valley • Discover the craftsmanship of creating porcelain, bunad brooches and aquavit • Tour churches, museums and meet local historielag members If you are interested in participating in the Gudbrandsdalslag tour, please contact: JIM OLSON, Lag President BREKKE TOURS [email protected] [email protected] 605-332-1321 1-800-437-5302 Photography courtesy of: Ian Brodie/Lillehammer.com Gudbrandsdalslag of America presents... A JOURNEY THROUGH THE HEART OF NORWAY August 18 - 31, 2019 TOUR HIGHLIGHTS Oslo, Skien, Rjukan, Kongsberg, Elverum, Vågåmo, Bøverdal, Otta, Vinstra and Lillehammer Join the Gudbrandsdalslag of America on a 14-day journey featuring Norway’s natural beauty, history and culture. Spend time exploring Telemark, Hedmark, Gudbrandsdal and Norway’s capital city of Oslo. DAY 4 WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 21 [B,L,D] ITINERARY | 14 DAYS Skien―Rjukan: Morning drive to Morgedal. Tour ITINERARY INCLUDES the Norwegian Ski Adventure Center. Continue to the Hardangervidda National Park Center for lunch. Learn • Roundtrip airfare from Mpls / St. Paul, including about the thousands of wild reindeer roaming the taxes, fees and fuel surcharge Hardangervidda Plateau through a variety of interactive • 12 nights accommodations, 1st class/superior exhibits. -

Fagrapport Sykehuset Innlandet Deltema 6 Infrastruktur

ADRESSE COWI AS Karvesvingen 2 Postboks 6412 Etterstad 0605 Oslo TLF +47 02694 WWW cowi.no DESEMBER 2020 HELSE SØR-ØST RHF SAMFUNNSANALYSE SYKEHUSSTRUKTUR INNLANDET - DELTEMA INFRASTRUKTUR OPPDRAGSNR. DOKUMENTNR. A209187 - VERSJON UTGIVELSESDATO BESKRIVELSE UTARBEIDET KONTROLLERT GODKJENT 1.0 2020-12-03 Fagrapport Øystein Berge Marius Fossen Øystein Berge SAMFUNNSANALYSE SYKEHUSSTRUKTUR INNLANDET 2 DELTEMA INFRASTRUKTUR DOKUMENTINFORMASJON Rapporttittel: Samfunnsanalyse Sykehusstruktur Innlandet Deltema Infrastruktur Dato: 03.12.2020 Utgave: Endelig Oppdragsgiver: Helse Sør-Øst RHF Kontaktperson hos Rune Aarbø Reinaas Helse Sør-Øst RHF: Konsulent: COWI AS og Vista Analyse Prosjektleder hos Øystein Berge, COWI konsulent: Utarbeidet av: Øystein Berge Sidemannskontroll: Marius Fossen Godkjent av: Øystein Berge SAMFUNNSANALYSE SYKEHUSSTRUKTUR INNLANDET 3 DELTEMA INFRASTRUKTUR INNHOLD 1 Sammendrag 4 2 Innledning 5 2.1 Bakgrunn 5 2.2 Alternativene 6 2.3 0-alternativet 7 3 Metode og kunnskapsgrunnlag i denne fagrapporten 8 4 Dagens situasjon og beskrivelse av 0-alternativet 9 5 Konsekvenser av ulike alternativer 11 5.1 Alternativ Biri-Hamar 11 5.2 Alternativ Biri-Elverum 11 5.3 Alternativ Moelv-Lillehammer 12 5.4 Alternativ Moelv-Gjøvik 13 5.5 Alternativ Brumunddal-Lillehammer 13 5.6 Alternativ Brumunddal-Gjøvik 14 6 Samlet vurdering 15 7 Bibliography 16 SAMFUNNSANALYSE SYKEHUSSTRUKTUR INNLANDET 4 DELTEMA INFRASTRUKTUR 1 Sammendrag Det er lite som skiller alternativene fra hverandre. Alle stedene utnytter eksisterende og kommende infrastrukturen på en god måte. Alle alternativene for Mjøssykehuset vil utnytte den nye E6en, men kun Moelv og Brumunddal kan utnytte kan jernbaneforbindelsen, og kommer derfor bedre ut. Blant de fire byene som er aktuelle for akuttsykehus har alle jernbanetilgang. Men hyppigst avganger er det på Hamar og i Lillehammer. -

Academic Achievements Among Adolescent School Children. Effects of Gender and Season of Birth

European Journal of Education and Psychology © Eur. j. educ. psychol. 2012, Vol. 5, Nº 2 (Págs. 149-160) ISSN 1888-8992 // www.ejep.es Academic achievements among adolescent school children. Effects of gender and season of birth Reidulf G. Watten1 and Veslemoy P. Watten2 1Lillehammer University College, Lillehammer (Norway), 2Hadeland Neuropsychological Centre, Gran (Norway) We have investigated gender differences in academic achievements in two age cohorts of students from the Lower Secondary School in Norway (2000, 2005; 15-16 year olds). In the 2000 and 2005 cohorts the female students outperformed male students in twelve out of thirteen academic disciplines, including mathematics and nature-science. Physical education was the only discipline where the male students had higher grade points than the female students. In both cohorts the results showed a significant effect of season of birth: Students who were born in the Nordic winter-spring season had slightly higher grade points than students born in the summer-autumn season. There was no significant interaction between gender and season of birth. Keywords: Academic achievements, gender, adolescents, season of birth. Logros académicos entre adolescentes escolares. Diferencias de género y de la estación del año en que nacieron. Hemos investigado las diferencias de género en los logros académicos en dos cohortes de edad de estudiantes de la Escuela media en Noruega (2000, 2005; de 15-16 años de edad). En los cohortes de 2000 y 2005 las estudiantes sobresalieron en rendimiento en comparación con sus compañeros varones en 12 de 13 disciplinas académicas, incluyendo matemática y ciencias naturales. Educación física fue la única disciplina donde los varones obtuvieron mayores puntuaciones que sus compañeras de estudios. -

Lillehammer Olympic Park

LILLEHAMMER OLYMPIC PARK Olympic City: Lillehammer Country: Norway Edition of the Games: 1994 Winter Olympic Games Preliminary remarks As you may have seen, two governance cases are dedicated to Lillehammer. Reasons that support this choice are twofold. First, Lillehammer hosted two editions of the Games. If the latter built upon the former to deliver great Games, it also produced its own legacy and consequently, structures to deal with it. Second, as legacy is about both venues and facilities at one side and education, knowledge transfer and experience sharing at the other side, two different cases were necessary to encompass various ways Lillehammer manages its Olympic legacy(ies). Inherited from the 1994 Games, the Lillehammer Olympic Park is a structure run by the municipality of Lillehammer that takes care of the majority of Olympic venues and events. The Lillehammer Olympic Legacy Sports Centre is an emanation of the Norwegian Sports Federation and Olympic and Paralympic Committee and is a direct legacy of the YOG. Obviously, many bridges and crossovers exist between these structures and collaboration and common understanding are key. The big picture also encloses the Norwegian Top Sports Centre of the Innland region dedicated to elite athletes (Olympiatoppen Innlandet), the University, the Olympic Legacy Studies Centre as well as the remaining Olympic venues run by other municipalities or private companies. With all these partners involved in managing Lillehammer’s Olympic legacy, clusters (venues, events, training, research, etc.) facilitate organisation and legacy management. Toolkit: Keeping the Flame Alive – Lillehammer Olympic Park 1 World Union of Olympic Cities 2019 HOW LEGACY GOVERNANCE STARTED IN LILLEHAMMER Since 1990 Lillehammer & Oppland https://www.olympiaparken.no/en/ • • • WHEN WHERE WEB ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… “The XVII Winter Olympics did not exist. -

Sources of Environmental Contaminants Into Lake Mjøsa Action-Oriented Prestudy

Sources of Environmental Contaminants into Lake Mjøsa Action-oriented prestudy Report: NILU OR 44/2005 TA number: (TA-2144/2005) ISBN: 82-7655-280-3 Ordered by: Norwegian Pollution Control Authority (SFT) Executing agency: Norwegian Institute for Air Research (NILU) Authors: Knut Breivik, Martin Schlabach, Torunn Berg Sources of Environmental Contaminants into Lake Mjøsa Action-oriented prestudy Discharge of Environmental Contaminants into Lake Mjøsa: Action-oriented prestudy Preface The purpose of this action-oriented prestudy has been to gain insight on the sources that control contemporary levels of selected environmental contaminants in Lake Mjøsa. The study was led by the Norwegian Institute for Air Research (NILU), with the help of Eirik Fjeld and Gösta Kjellberg of the Norwegian Institute for Water Research (NIVA). We would like to thank the Norwegian Pollution Control Authority (SFT) for funding this project, and the Norwegian Research Council for funding supplementary PBDE measurements. We would also like to thank the people who have contributed useful information to the project work. This particularly applies to Eirik Fjeld and Gösta Kjellberg at NIVA, who have been of invaluable help in connection with sample collection during this project and data collection from previous studies. We would also like to thank Elin Lundstad (Norwegian Meteorological Institute) for meteorological data for Kise, employees of the Norwegian Centre for Soil and Environmental Research (Jordforsk) for samples from treatment plants along Lake Mjøsa, and Sverre Solberg (NILU) for trajectory calculations. We would also like to thank the people who have assisted with the sample collection, and the employees who were involved with this work at the Norwegian Crop Research Institute in Kise. -

ISU Communication 1972

INTERNATIONAL SKATING UNION Communication No. 1972 Judges Draw by number Single & Pair Skating/Ice Dance for the Winter Youth Olympic Games 2016 - Lillehammer The draw by number for the above-mentioned event was held on October 15, 2015, at the “Hôtel de la Paix” in Lausanne in the presence of Mrs. Marie Lundmark, ISU Council Member, Mr. Peter Krick, Sport Manager Figure Skating, Mr. Charlie Cyr, Ms. Krisztina Regöczy, Sport Directors Figure Skating, Ms. Helena Kara, BDO Auditor and various delegates from ISU Members. Members drawn to nominate Judges: Member Men Ladies Pairs Ice Dance CAN P1 1 1 CHN P1 ALT 2 1 CZE P1 1 1 FIN ALT 2 ALT 4 FRA 1 1 GER ALT 1 ALT 1 1 GBR P1 1 HUN 1 ISR ALT 1 ITA 1 P1 1 1 JPN ALT 4 ALT 3 LAT 1 NOR 1 POL 1 KOR ALT 3 P1 1 RUS P1 1 1 1 SVK 1 UKR 1 P1 1 1 USA P1 1 1 1 9 9 9 9 Judges marked with P are Judges coming from the Pair panel. Therefore the Judge must be the same for the Pair Skating panel and for the Men or Ladies panel. 4 Alternate judges (who are not on site) have been drawn for Men and Ladies. If there is no alternate Judge indicated above and should there be a withdrawal, the replacement Judge would be selected from the Junior Grand Prix final standings (see Communication No. 1971). Judges entries by name (including Alternates) must be sent by the drawn Members by e-mail and/or fax, to the ISU Secretariat ([email protected] – fax no +41- 21 612 66 77) and LYOGOC Ms. -

Kartlegging Av Virksomheter Og Næringsområder I Mjøsbyen Mars 2019

Foto: Magne Vikøren/Moelven Våler Kartlegging av virksomheter og næringsområder i Mjøsbyen Mars 2019 FORORD Rapporten er i hovedsak utarbeidet av Marthe Vaseng Arntsen og Celine Bjørnstad Rud i Statens vegvesen. Paul H. Berger i Mjøsbysekretariatet har vært kontaktperson for oppdraget. Aktørene i prosjektgruppa for Mjøsbysamarbeidet har bidratt med innspill og kvalitetssikring. Data er innhentet og bearbeidet av Ingar Skogli med flere og rekkeviddeanalyser med ATP- modellen er utført av Hilde Sandbo, alle fra Geodataseksjonen i Statens vegvesen Region øst. Mars 2019 2 Innhold 1. Innledning og bakgrunn .................................................................................................... 4 2. Befolkningssammensetning i Mjøsbyen ............................................................................ 4 2.1 Befolkningsutvikling ..................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Pendlingsforhold og sysselsatte ................................................................................... 8 3 Metode – «Rett virksomhet på rett sted» ........................................................................... 14 3.1 ABC-metoden ............................................................................................................. 14 3.2 Kriteriesett for Mjøsbyen ............................................................................................ 15 3.2.1 Virksomhetene .................................................................................................... -

Cross Country Skiing in Lillehammer, Norway Feb 29 – Mar 13, 2020 At# 2001

CROSS COUNTRY SKIING IN LILLEHAMMER, NORWAY FEB 29 – MAR 13, 2020 AT# 2001 TRIP RATING – Moderate (3) WOW! Norway in winter! The Mecca of cross country skiing and the medal leader in the 2018 Olympics! Come join us on this adventure as we explore Oslo’s cultural sites and then travel on to the Lillehammer area where we’ll have access to hundreds of cross country ski trails. The area caters to winter sports enthusiasts with easy transportation via “ski bus” to the nearby villages and trails. The region is famous for having lots of snow well into spring. Our adventure will start with three nights stay in Oslo, the capital of Norway, which sits on the country’s southern coast at the head of the Oslofjord. It’s known for its green spaces and museums. Many of these are on the Bygdøy Peninsula, including the waterside Norwegian Maritime Museum and the Viking Ship Museum, with Viking ships from the 9th century. The Holmenkollbakken is a ski- jumping hill with panoramic views of the fjord. It also has a ski museum. We’ll each have a 72 hour Oslo card which provides for free use of all public transportation, free entrance into museums, city tour, fjord boat excursion and lots more. Surrounded by mountains and the sea, this compact, cultured, caring and fun city is Europe's fastest-growing capital, with a palpable sense of reinvention. From Oslo, we’ll travel by train to Lillehammer and our home for the next 8 nights! Lillehammer (27,000 inhabitants) is considered Norway's oldest winter sports resort and was host of the 1994 Winter Olympics. -

A Timber Bridge Across Lake Mjøsa in Norway Summary

A timber bridge across Lake Mjøsa in Norway Svein Erik Jakobsen M.Sc. from Norwegian Institute Director of Technology from 1984. Joined the company Aas- Aas-Jakobsen Jakobsen in 1985 and is Oslo, Norway currently Director of the Bridge [email protected] Department. Trond Arne Stensby Project Manager Norwegian Public Roads Administration Hamar, Norway [email protected] Widar Mikkelsen Project Manager Norwegian Public Roads Administration Hamar, Norway [email protected] Yngve Årtun M.Arch. from Norwegian Chief Architect Institute of Technology from 1983. Joined the company Plan Plan Arkitekter AS Arkitekter as a partner in 1996. Trondheim, Norway Specialist in bridge aesthetics [email protected] and timber bridges. Per Meaas M.Sc. from Norwegian Institute Project Manager of Technology from 1974. Joined the company Aas- Aas-Jakobsen Jakobsen in 1976 and is Project Oslo, Norway Manager for several Major [email protected] Infrastructure Projects. Summary Pre-studies are performed on how to cross Lake Mjøsa in Norway for a new 4-lane link on Highway E6 between the cities Hamar and Lillehammer. Preliminary design is also performed for timber bridges in several alternatives. The timber alternatives are truss bridges with two underlay timber trusses composite with a concrete bridge deck. Typical span width is 69m. Main spans are suggested to be cable stay spans with the same timber truss solution and span widths 120.75m. Total length of the bridge is approximately 1650m. The conclusions from preliminary design in accordance to ref. [1] have been that a concrete extradosed alternative or a timber truss alternative with cable stayed main spans is to be preferred. -

Oppgaver Og Funksjoner I Kongsvinger Sykehus

2016 Oppgaver og funksjoner i Kongsvinger sykehus Utredning av helseforetakstilhørighet for Sykehuset Innlandet Kongsvinger 13.12.2016 Oversikt oppgaver og funksjoner i Kongsvinger sykehus 2016 Sykehuset i Kongsvinger ble i 2003 en del av Sykehuset Innlandet. Dette er en helhetlig beskrivelse av dagens aktivitet i sykehuset i Kongsvinger. Somatikk, psykisk helse, BUP, prehospitale tjenester, medisinske- og ikke medisinske støttefunksjoner. Kort om lokal- og områdefunksjoner Oppdraget til SI Kongsvinger er å ivareta: Lokalsykehusfunksjoner akutt og elektivt for • Indremedisin (generell) • Kirurgi/ortopedi • Akuttmedisin/traume • Poliklinikker • Fødeavdeling/gyn Befolkningen i opptaksområdet er ca. 42 000 innbyggere i Glåmdalskommunene Kongsvinger, Eidskog, Grue, Sør Odal og Nord Odal og de ca. 10 000 innbyggere i Nes kommune (Akershus fylke) som benytter det somatiske lokalsykehustilbudet. I tillegg finner en, for 100 000 innbyggere i Hedmark, et behandlingstilbud innen Revmatologi. Til sammen 10 fagområder er representert i sykehuset. Fagområde Type/aktivitet Antall senger Lokalitet Somatikk Normerte senger 88 Kongsvinger Indremed 34 (Senger Gen kirurgi 24 benyttes Ortopedi 12 fleksibelt Revmatologi 8 mellom Føde/barsel/gyn 8/2 postene) Tekniske senger (po/intensiv) 9/6(7) Somatikk Mulig kapasitetsøkning 31-38 Kongsvinger Psykisk DPS 14 Kongsvinger helsevern Akuttpsykiatri, psykose 9 Sanderud og rus Alderspsykiatri 3 Sanderud Sikkerhetspsykiatri 2 Reinsvoll BUP <1 Kongsvinger Rus og avhengighet 2,5 Sanderud Mulig kapasitetsøkning er avhengig av flere forhold, da dagens aktivitet benytter all tilgjengelig sengekapasitet i «høyblokka». Vi har valgt å unnta rom i den eldste bygningsmassen – der er standard på rommene ikke egnet til pasientrom. Alle sengepostene i «høyblokka» er bygd like, med plass til 29 senger Per i dag benyttes 29 senger i 3. -

Høringsuttalelse Fra "Nettverket for Regional Fjellgrense I Lillehammer, Ringsaker Og Øyer"

Høringsuttalelse fra "Nettverket for regional fjellgrense i Lillehammer, Ringsaker og Øyer" Vi viser til varsel om oppstart av regulering og offentlig ettersyn av planprogram for adkomstveger til Lunkelia. Det er Areal+ på vegne av Phil AS som har utarbeidet planprogrammet. Lunkelia er avsatt til fritidsbebyggelse i kommuneplanens arealdel (vedtatt 10.9.2014, revidert 17.6.2015). Det er imidlertid ikke avsatt areal til adkomstveg frem til Lunkelia i den gjeldende kommuneplanen. Området: Planområdet Lunkelia, beliggende sentralt på Sjusjøen helt nord i Ringsaker kommune, tett opp mot kommunegrensa til Lillehammer. Området Heståsmyra/Lunkefjell er et regionalt viktig natur- og friluftsområde, og framstår som et friareal og grønn lunge der den strekker seg mot fjellet. Brukerne her er mange, ikke bare hytteeiere på Nordseter/Sjusjøen, men tilreisende turister så vel som lokalbefolkning bruker området året gjennom. Løyper og stier inngår i et nett som strekker seg fra Rondane/Dovre i nord og sørover til Gåsbu/Budor. Gjennom selve planområdet går de viktige skiløypene Fjelløypa og Skogsløypa, og Birkebeinerløypa passerer like ved. Disse løypene, som er svært populære, vil kunne bli berørt og få redusert opplevelsesverdi om det bygges veg og hytter i området. Vårt synspunkt: Vi i "Nettverket for regional fjellgrense i Lillehammer, Øyer og Ringsaker" har i lengre tid påpekt behovet for en helhetlig forvaltning av det nevnte fjellområdet. Dette for å sikre at en framtidig hytteutbygging i tilstrekkelig grad ivaretar naturkvaliteter, landskapsverdier, allmennhetens mulighet til tradisjonelt friluftsliv og landbrukets behov for gode beiteområder i et langsiktig perspektiv. En mer helhetlig tilnærming vil også være en styrke dersom en ønsker å utnytte dette hyttemarkedet som vekstimpuls i næringsøyemed, sikre veloverveide vare- og handelsetableringer, og gode, klimavennlige transportløsninger i regionene for å nevne noe. -

SALT LAKE CITY 28 Sept 2001

ELECTING THE HOST CITY OF THE OLYMPIC WINTER GAMES Since the reforms that were put in place in December 1999, all cities wishing to organise the Olympic Games, or applicant cities, are appraised by an Evaluation Commission, partly composed of experts, who draft a report on the city’s ability to organise the Games. These reports are studied by the Executive Board who can thus decide which applicant cities are suitable to become candidate cities. The Evaluation Commission produces a second evaluation report, which is then submitted to the IOC members who elect the city of their choice. How times have changed! In 1955, when Alexandre Cushing suggested the candidature of Squaw Valley to the IOC, the resort did not even exist. He was the sole inhabitant and homeowner of the town, which was 300km from San Francisco and 1900m above sea level. Another reform implemented was the cessation of visits by IOC members to candidate cities. A contract containing obligations, a code of conduct and sanctions in case of any breach of the rules is drawn up between the IOC, each candidate city and the NOC of its country. - The host city of future Olympic Games is selected seven years before the Games are due to be held. - The Evaluation Commission for the Olympic Winter Games is composed of three members representing the IFs, three members representing the NOCs, four IOC members, one member proposed by the Athletes’ Commission, one member representing the International Paralympic Committee (IPC) as well as other specialists. - It was at the 91st Session in Lausanne in 1986 that the IOC decided to alter the timing of the Olympic Games.