HFCS: a Sweetener Revolution Robert D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Economic History of the United States Sugar Program

AN ECONOMIC HISTORY OF THE UNITED STATES SUGAR PROGRAM by Tyler James Wiltgen A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Applied Economics MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana August 2007 © COPYRIGHT by Tyler James Wiltgen 2007 All Rights Reserved ii APPROVAL of a thesis submitted by Tyler James Wiltgen This thesis has been read by each member of the thesis committee and has been found to be satisfactory regarding content, English usage, format, citations, bibliographic style, and consistency, and is ready for submission to the Division of Graduate Education. Chair Vincent H. Smith Approved for the Department of Agricultural Economics and Economics Myles J. Watts Approved for the Division of Graduate Education Carl A. Fox iii STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Montana State University, I agree that the Library shall make it available to borrowers under rules of the Library. If I have indicated my intention to copyright this thesis by including a copyright notice page, copy is allowed for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed in U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this thesis in whole or in parts may be granted only by the copyright holder. Tyler James Wiltgen August 2007 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am greatly indebted to Dr. Vincent Smith, my thesis committee chairman, for his guidance throughout the development of this thesis; I appreciate all of his help and support. In addition, I would like to thank the other members of the committee, Dr. -

Sugar Act, 2020

TI{E R:EPT'BI,IC OF UGAI{DA THE suGARAcr, 2020', PARLIAMENT LIBRARY I PO 8OX 7178, XAMPALA \ * 28APR?f;;3 * CALL NO TTIE REPUBLXC Otr UGAIIDA PARLIAMENT LIBRARY PO BOX 7178. KAMPALA * 7 8. APR ;i:I * CALL I sIcNIry my assent to the bill. t President Date of assent 3r^J Act Sugar Act 2020 TTM SUGAR ACT,2O2O. ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Section Penr I-PnsLrMrNARY 1. Commencement 2. Interpretation Panr II-UcnNoe Sucen Bonno 3. Establishment of the Uganda Sugar Board 4. Composition of the Board 5. Tenure of office of members of the Board 6. Remuneration of members of the Board PARLIAMENT LIBRARY PO BOX 7178. XAMPALA Functions of the Board * 2 t f":l l*"' * 7 . Functions of the Board ACC NO: 8. Cooperation with other agencies CALL NO:... 9. Powers of the Board 10. Powers of Minister 11. Meetings of the Board and related matters 12. Committees of the Board 13. Delegation of functions of the Board Penr Itr-STAFF oF rHp Boano t4 Executive director. 15 Functions of the executive director 16 Staff of the Board Penr IV-FTNANCES 17. Funds of the Board 18. Duty to operate in accordance with the Public Finance Management Act and sound financial principles Act Sugar Act 2020 Section Pexr V-LrcENsrNc on MrI-s 19. Licensing of mills 20. Application for a licence to operate mill 21. Processing, grant or refusal of licence 22. Modification of mill or plant Pnnr VI-Sucm INousrRY AcREEMENTS 23. Sugar industry agreements Penr VII-Sucnn CeNs PRlctNc 24. Sugar cane pricing Panr VIII-NATIoNAL Sucen Rrsrancs INsrtrure 25. -

Teacher Guide.Qxd

Classroom Materials developed by the New-YYork Historical Society as a companion to the exhibit Generous support provided by THE NEW-YYORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY Since its founding in 1804, the New-York Historical Society (N-YHS) has been a mainstay of cultural life in New York City and a center of historical scholarship and education. For generations, students and teachers have been able to benefit directly from the N-YHS’s mission to collect, preserve and interpret materials relevant to the history of our city, state and nation. N-YHS consistently creates opportunities to experience the nation’s history through the prism of New York. Our uniquely integrated collection of documents and objects are par- ticularly well-suited for educational purposes, not only for scholars but also for school children, teachers and the larger public. The story of New York’s rootedness in the enslavement of Africans is largely unknown to the general public. Over the next two years, the New-York Historical Society, together with the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, will stage two major exhibitions, with walking tours, educational materials and programs for learners of all ages. The first of these exhibits, entitled “Slavery in New York,” explores the vital roles enslaved labor and the slave trade played in making New York one of the wealthiest cities in the world. In bringing this compelling and dramatic story to the forefront of historical inquiry, “Slavery in New York” will transform col- lective understanding of this great city’s past, present and future. The enclosed resources have been devel- oped to facilitate pre- and post-visit lessons in the classroom and provide learning experiences beyond the duration of the exhibit. -

Sugar Regimes in Major Producing and Consuming Countries in Asia and the Pacific

SUGAR REGIMES IN MAJOR PRODUCING AND CONSUMING COUNTRIES IN ASIA AND THE PACIFIC Mr Kaison Chang, Senior Commodity Specialist, Sugar and Beverages Group, Commodities and Trade Division, FAO. INTRODUCTION Sugar is one of the world's most important crops and one, which is of prominence to countries represented here. It has widespread implications for the earnings and well being of farm communities, as well as for consumers of this important food item. Today it is my task to briefly introduce existing sugar regimes in selected countries in Asia. Before touching on some of the salient features of individual sugar regimes, it is useful to place the Asia and Pacific region in its global context in as far as production, trade and consumption of sugar are concerned. OVERVIEW Of the nearly 128 million tonnes of sugar produced globally more than 36 percent was produced in the Asia and Pacific region with major producing countries being Australia, China, India and Thailand. In terms of trade, the region accounted for 43 percent of global exports and 29 percent of imports in 1998. The major net exporting countries were Australia, Thailand, India and Fiji and net-importing countries included China, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia and the Republic of Korea. I would like to turn now to some of the features of individual policy in selected countries. My presentation is restricted to only a few countries due to time limitation. However, several more countries are included in the document that has been circulated. AUSTRALIA Introduction Australia's sugar industry is widely acknowledged as one of the lowest cost in the world. -

The Origins and Development of the U.S. Sugar Program, 1934-1959

The Origins and Development of the U.S. Sugar Program, 1934-1959 Richard Sicotte University of Vermont [email protected] Alan Dye Barnard College, Columbia University [email protected] Preliminary draft. Please do not cite. Paper prepared for the 14th International Economic History Conference August 21-25, 2006 1 Recent trade talks in the WTO indicate that the powerful US sugar lobby continues to be a roadblock to agricultural liberalization. It calls attention to a need for better understanding of the complex quota-based regulations that have governed the US sugar trade for so long. In 1934 the United States shifted its sugar protection policy from emphasizing the tariff to a comprehensive system of quotas. It was revised in 1937. After its suspension for much of World War II, a new Sugar Act was passed in 1948, and further revised in 1951 and 1956. It has been in almost continuous operation since 1934. This paper examines the origins and development of the Sugar Program from 1934 to 1959. Why did the United States adopt sugar quotas? What were the rules set up to implement and govern the policy? How did they function? The sugar quota was adopted after the U.S. government determined that the long-standing policy using the tariff to protect the domestic industry was failing. A principal reason was that the tariff was not raising the price of sugar because, by diminishing the imports of Cuban sugar, it was causing severe decline in wages and costs on that island. In turn, Cuban sugar was being offered at ever lower prices. -

Download 47.5 KB

ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK TAR:FIJ 36151 TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE TO THE REPUBLIC OF THE FIJI ISLANDS FOR INTERMEDIATION OF SUGAR SECTOR RESTRUCTURING June 2002 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 10 May 2002) Currency Unit – Fiji dollar (F$) F$1.00 = US$2.2247 US$1.00 = F$0.4495 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank FSC – Fiji Sugar Corporation GDP – gross domestic product MASLS – Ministry of Agriculture, Sugar and Land Settlement SCF – Sugar Commission of Fiji TA – technical assistance I. INTRODUCTION 1. In March 2002, an Asian Development Bank (ADB) Fact-Finding Mission visited the Fiji Islands to review the possible role of ADB in assisting the rehabilitation of the sugar industry. The Mission held in-depth discussions with relevant agencies including the Sugar Commission of Fiji (SCF);1 the offices of the Sugar Tribunal; the Fiji Sugar Corporation (FSC); and the Ministry of Agriculture, Sugar and Land Settlement (MASLS). Extensive discussions were also held with workers, farmers, and representatives of indigenous Fijian groups. Field visits were made to sugar-growing areas. 2. The Mission found that the sugar sector is on the verge of a profound transformation. The industry is facing a major restructuring and a possible significant reduction in size as it adapts to a pending loss of preferential tariffs within 6 years. At the same time, significant changes are taking place in landholding patterns as longstanding smallholder leases expire, landowners reclaim their lands, and former sugarcane growers are forced to find other sources of income. In addition, the processing infrastructure of FSC––the mainly Government-owned processing corporation––is seriously degraded, and the company is in poor financial straits. -

The Costly Benefits of the US Sugar Program

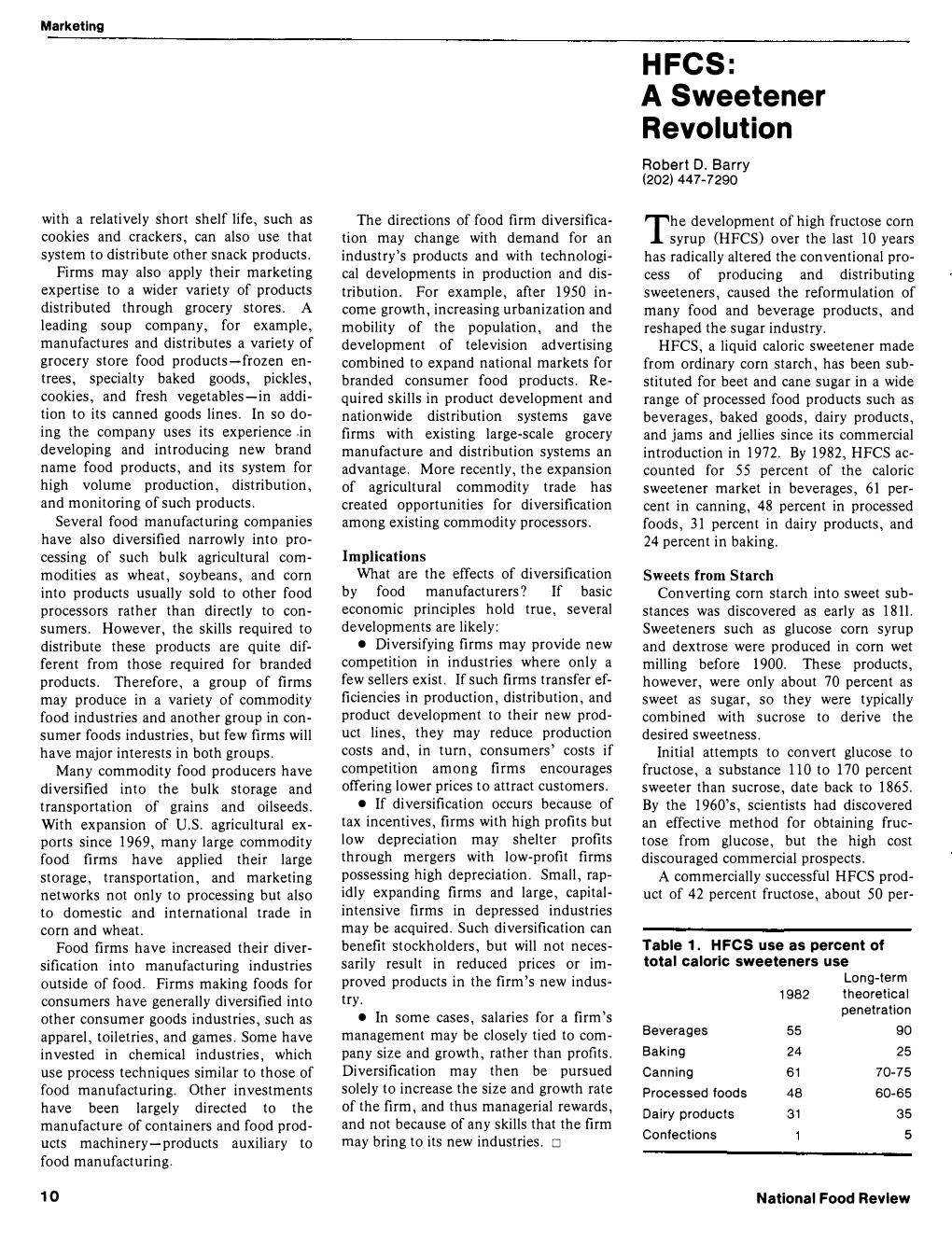

Sweets for the Sweet The Costly Benefits of the US Sugar Program by Michael K. Wohlgenant Sweets for the Sweet The Costly Benefits of the US Sugar Program by Michael K. Wohlgenant Introduction The US sugar industry receives enormous government support and protection from foreign competition. The sugar program has changed over time, becoming a complex set of rules developed to promote sugar production primarily at the expense of domestic consumers. The program has also affected foreign producers and consumers through import restrictions that have significantly reduced the world sugar price. Since the mid-1970s, as a result of the sugar program, the price of sugar in the United States has been almost twice as high as the price of sugar on the world market in most years. Michael K. Wohlgenant ([email protected]) is the William Neal Reynolds Distinguished Professor in the Department of Agricultural & Resource Economics at North Carolina State University. 1 The resulting estimated costs to US consumers program on the mix of sweeteners and mix of have averaged $2.4 billion per year, with producers sugars. Policy recommendations are provided in benefiting by about $1.4 billion per year. So the net the conclusion. costs of income transfers to producers have averaged about $1 billion per year. Distortions due to the Structure of the US Sugar Industry sugar program have also led to the development of the high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) industry and extensive use of HFCS as a substitute for sugar in Sugar in the United States is produced using soft drinks and other sweetened products. -

The United States Vs. Big Soda: the Taste of Change

The United States vs. Big Soda: from the west and east coast based on the desired use for the revenue. The Taste of Change In order to understand taxing of sugar Hannah Elliott drinks, it is imperative to look back on what has La Salle University happened in legislation, in terms of the taxing of soft drinks. Beginning in the American colonies in the early 1700s, taxation on sugar existed and was Robert Lustig, a pediatric endocrinologist regarded as undesirable and unpopular among the who specializes in childhood obesity once said, colonists. One of the earliest forms of sugar taxing “Sugar is celebratory. Sugar is something that we was the Molasses Act, also known as the used to enjoy. It is evident that now, it basically has Navigation Act of 1733. This act was inflicted by coated our tongues. It’s turned into a diet staple, and the British on the colonists and entailed, “a tax on it’s killing us.”1 In the past decade the prevalence of molasses, sugar, and rum imported from non-British sugar in American processed food and diet has foreign colonies into the North American become a growing domestic concern. It is evident colonies.”4 The colonists were under British rule at that now more than ever, sugar has found its way the time and this tax was imposed out of fear of into almost every food and drink consumed by competition with foreign sugar producers. The Americans, “The United States leads the world in American colonists were unhappy with the tax and consumption of sweeteners and is number 3 in the felt that the British would not be able to supply and world in consuming sugary drinks.”2 Sugar alters meet the colonists demand in molasses. -

A History of Sugar Marketing Through 1974

A HISTORY OF SUGAR MF.RKETING THROUGH 1974 14d :: ' t.,\; "''',.':- · ' ''t,: " '"' ,,.,· .........~.~, ~'"~ ,'~-''~~''', ' ' .. ~,~. ,..'... I;."', · , .;~.~'~, .'k'"" :O ,... ' :,'~.~..: I <' '". - . L~b~ I .. ' ', '.;., U..DEATEN FAGIUTUEECNMCS TTITC, N COEATVSSEVC AGR~~~~~ICUTRLEOOICRPR O 8 U. S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE ECONOMICS. STATISTICS, AND COOPERATIVES SERVICE AGRICULTURAL ECONOMIC REPORT NO. 382 ABSTRACT The quota system of regulating the production, importation, and marketing of sugar in the United States through 1974 was an outgrowth of Government regulation of the sugar trade dating from colonial times. Similar systems have developed in most other countries, particu- larly those which import sugar. The U.S. Sugar Quota System benefited domestic sugar pro- ducers by providing stable prices at favorable levels. These prices also encouraged the produc- tion and use of substitute sweeteners, particularly high fructose and glucose sirup and crystalline dextrose in various industries. But sugar is still the most widely used sweetener in the United States, although its dominant position is being increasingly threatened. KEYWORDS: Sugar, quota, preference, tariff, refined, raw, sweeteners, corn sweeteners, world trade. PREFACE This report was written in 1975 by Roy A. Ballinger, formerly an agricultural economist in the Economic Research Service. It supersedes A History of Sugar Marketing, AER-197, also by Ballinger, issued in February 1971 and now out of print. On January 1, 1978, three USDA agencies-the Economic Research Service, the Statistical Reporting Service, and the Farmer Cooperative Service-merged into a new organization, the Economics, Statistics, and Cooperatives Service. Washington, D.C. 20250 March 1978 CONTENTS Page Summary ........................................ ii Introduction ........................................................... 1 Sugar Before the Discovery of America ....................................... 1 The Colonial Period in the Americas ....................................... -

Road to Revolution

Road to Revolution 1760-1775 In 1607 The Virginia Company of London, an English trading company, planted the first permanent English settlement in North America at Jamestown. The successful establishment of this colony was no small achievement as the English had attempted to plant a colony in North America since the reign of Queen Elizabeth I in the l6th century. The Virginia Company operated under a royal charter, granted by King James I, which assured the original settlers they would have all liberties, franchises and immunities as if they had been “abiding and born within England.” By 1760, England and Scotland had united into the Kingdom of Great Britain and her settlements in North America had grown to thirteen thriving colonies with strong cultural, economic, and political ties to the mother country. Each colony enjoyed a certain amount of self- government. The ties which bound Great Britain and her American colonies were numerous. Wealthy men in the colonies, such as George Washington, used British trading companies as their agents to conduct business. Young men from prominent families, like Arthur Lee, went to Great Britain to finish their schooling. Colonial churches benefited from ministers who were educated in Great Britain. Many of the brightest men in the colonies, such as Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, James Otis of Massachusetts, and Peyton Randolph of Virginia, served the British government as appointed officials. What then caused these strong ties to unravel after 1760? What caused the American colonists to revolt against their mother country in 1775? Though not recognized by most people at the time, economic and political forces beginning in 1760 on both sides of the Atlantic would force Great Britain and her American colonies to reassess their long relationship. -

Social Studies - Grade 5 Monday, May 18 – Friday, May 22

Social Studies - Grade 5 Monday, May 18 – Friday, May 22 PURPOSE Grade Level Expectation: 5.10.1 (New Material) I can explain how the events and outcome of the French and Indian War impacted the British Colonists. WATCH Monday: (Review of Learning) Focus Question: What happened during the French and Indian War? Watch the Video and read the text below the video screen: https://www.ducksters.com/history/colonial_america/french_and_indian_war.php Tuesday: (Review of Learning – Causes and New Learning - Effects) Focus Question: How did the French and Indian War effect the British and the American Colonists? Watch the video and pay special attention to the effects of the French & Indian War: https://youtu.be/GUyW5O8ip5E (NOTE: This is a teacher created video and she mentions she will discuss more in class tomorrow – please note this does not apply) Wednesday: (New Learning) Focus Question: What happened after the French and Indian War was over? View: The Royal Proclamation video: https://youtu.be/HKNTBHmWOyA Thursday: (New Learning) Focus Question: What were the Sugar, Stamp, and Quartering Acts, and why were they passed? Sugar & Stamp Act video: Watch: https://youtu.be/YjObnYk6AVY (NOTE: This is a teacher created video and she mentions she will discuss more in class tomorrow – please note this does not apply) Quartering Act: Watch: https://youtu.be/jKnN8Jg36kA PRACTICE Monday: Review of the French and Indian War: Take the short online quiz about today’s video. Quiz about the video: https://www.ducksters.com/history/colonial_america/french_and_indian_war_questions.php Tuesday: After viewing the video, please complete the T-Chart noting the causes and effects of the French and Indian War. -

And the Th 4Of

MOLASSES and theSticky ORIGINS of the thAMENDMENT Molasses.1 Molasses gave us the Fourth Amendment. Yes, that sticky, dark brown stuff, practically a food group in Southern cooking, is why we have the Fourth Amendment with all the case law, statutes and arguments related to search and seizure. Take away this uniquely American ingredient and we would have a different Constitution.2 Take molasses out of the mix and we 44would have a different nation. Sure, America inherited legal notions of protecting a person’s house and papers from England, embodied in the saying “A man’s home is his castle.” This English source is especially reflected in the Fourth Amendment’s first clause: the reasonableness clause. But it BY ROBERT J. MCWHIRTER is the American ingredient (i.e., molasses) that was the crucial American foundation of the Fourth Amendment’s second clause: Robert J. McWhirter is a senior lawyer at the Maricopa Legal Defender’s the warrants clause. Office handling serious felony and death penalty defense. His publications So what was the big deal about molasses? Surely Colonial include THE CRIMINAL LAWYER’S GUIDE TO IMMIGRATION LAW, 2d ed. (American Americans could not have consumed or sold sufficient quantities of Bar Association 2006). This article is part of the author’s book in progress on Boston Baked Beans or sugar cookies to make an economic differ- the “History Behind the History of the Bill of Rights.” ence. The answer is that molasses was New England’s commercial The author thanks several friends who contributed good editorial com- lifeblood in the 18th and 19th centuries.