Consumer Awareness Campaigns on Food Standards and Safety

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fy19-Astar-Annual-Report.Pdf

CONTENTS About A*STAR 2 2 Our Mission and Vision OUR OUR 4 Message from the Chairman and CEO 5 Board Members MISSION VISION 6 Senior Management 7 Organisation Chart The Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) A global leader in science, technology and open innovation. 8 Subsidiary Company drives mission-oriented research that advances scientific 8 Our Community discovery and technological innovation. We play a key role in A*STAR is a catalyst, enabler and convenor of significant nurturing and developing talent and leaders for our research research initiatives among the research community in Singapore Special Feature: institutes, the wider research community, and industry. and beyond. Through open innovation, we collaborate with Supporting Singapore’s Fight our partners in both the public and private sectors, and bring Our research creates economic growth and jobs for Singapore. science and technology to benefit the economy and society. Against COVID-19 As a Science and Technology Organisation, we bridge the gap 9 between academia and industry in terms of research and 11 Diagnostic Kits and development. In these endeavours, we seek to integrate the Complementary Systems relevant capabilities of our research institutes and collaborate 14 Antibody Discovery and Therapeutics with the wider research community as well as other public 15 Bioinformatics and Modelling Studies sector agencies towards meaningful and impactful outcomes. 16 Protective Face Masks 17 Analytics and Detection Together with the other public sector entities, we develop industry sectors by: integrating our capabilities to create impact with multi-national corporations and globally competitive Key Achievements companies; partnering local enterprises for productivity and 18 gearing them for growth; and nurturing R&D-driven start-ups by 19 Contributing to Better Health seeding for surprises and shaping for success. -

COVID-19 Update Corner: Sector Specific Government Advisories

Singapore COVID-19 Update Corner: Sector Specific Government Advisories Welcome to our Singapore COVID-19 Update Corner where you will get regular bite-sized updates on the latest COVID-19 related legal and regulatory developments and guidelines issued by the Singapore government. On 3 April 2020, the Singapore government announced "circuit-breaker" measures to curb the spread of COVID-19 within the local community. These measures, further information of which are in the table below, took effect from 7 April 2020 and remain in force until 1 June 2020 (inclusive), subject to a further extension by the government. Compiled in the table below are COVID-19 sector specific advisories which we have put together from the gov.sg websites:- https://www.gov.sg/article/covid-19-sector-specific-advisories https://www.gov.sg/article/covid-19-updates-and-announcements Update highlights as of 29 May 2020 1. The MOF’s “Singapore Fortitude Budget (26 May 2020)” at [56]. The MOFs “Singapore Fortitude Budget (26 May 2020)” at [56] explains that S$33 Billion has been set out to help Singapore’s economy recover and emerge stronger from the circuit breaker measures. Some of the key measures are included below: Enhanced Support for Households through GST Vouchers, Workfare, cash give outs and etc. Enhanced Support for Businesses & Self-employed through extension of the Jobs Support Scheme till Aug 2020 with enhancements for specific sectors, enhanced hiring incentives, property tax rebates, waivers for Foreign Worker Levy and etc. Support for young families through CPF Housing Grants, Baby Bonus, support for pre-school services, cash give outs and etc. -

Covid-19 Advisory: Adjournment of Non-Essential and Non-Urgent Matters

COVID-19 ADVISORY: ADJOURNMENT OF NON-ESSENTIAL AND NON-URGENT MATTERS All non-essential and non-urgent matters scheduled to be heard between 5 May and 1 June 2020 in Court 4A(N), 4B(N), 7(A) and 7(B) will be adjourned. Rescheduled Hearings COURT 4A(N) Original New Court Date Agency S/N Court Date Time: 5.30pm 1 5 May 2020 16 June 2020 National Environment Agency [NEA] Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority [ACRA] 2 6 May 2020 17 June 2020 Central Provident Board [CPF] Jurong Town Corporation [JTC] Singapore Food Agency [SFA] 11 May 2020 Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore [IRAS] 3 22 June 2020 Town Councils and Private Summons Cases 4 12 May 2020 23 June 2020 National Environment Agency [NEA] Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority [ACRA] 5 13 May 2020 24 June 2020 Central Provident Board [CPF] Jurong Town Corporation [JTC] Singapore Food Agency [SFA] Housing and Development Board [HDB] 6 18 May 2020 6 July 2020 Urban Redevelopment Authority [URA] 7 19 May 2020 30 June 2020 National Environment Agency [NEA] Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority [ACRA] 8 20 May 2020 1 July 2020 Central Provident Board [CPF] Jurong Town Corporation [JTC] Singapore Food Agency [SFA] 9 26 May 2020 7 July 2020 National Environment Agency [NEA] 1 Havelock Square Singapore 059724 T 1800 5878 423 (1800 JUSTICE) www.statecourts.gov.sg COURT 4A(N) Original New Court Date Agency S/N Court Date Time: 5.30pm Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority [ACRA] 10 27 May 2020 8 July 2020 Central Provident Board [CPF] Jurong Town Corporation -

Together As One

STANDING TOGETHER AS ONE ISSUE focus 70 The Republic’s spirit of unity comes to the fore in the wake of a pandemic. IN THIS ISSUE 6 8 10 AFTER THE ROAD TO SHARING ACROSS THE STORM SELF-SUFFICIENCY BORDERS IN THIS ISSUE 3 STRONGER TOGETHER ED´S NOTE #SGUNITED, a widely-used hashtag on social media in Singapore, encapsulates the Republic’s spirit of Dear readers, unity and esprit de corps amid the COVID-19 pandemic As we grapple with the wide-ranging effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, governments and people around the world have come to realise that, 6 despite all the uncertainties, one thing is for sure — the world has changed, perhaps irrevocably. As with all crises, we can either accept the reality and AFTER THE STORM ‘brace for impact’, or adapt and turn adversity into opportunity. Like many Putting the spotlight on how nations, Singapore has opted for the latter. Our Focus story (pages 3-5) partnerships can help countries looks at how Singapore is working together to contain the outbreak through emerge from COVID-19 sophisticated contact tracing efforts, and by ramping up the provision of 8 healthcare services. The onslaught of the virus has exposed economic, social and THE ROAD infrastructural vulnerabilities in many countries. For small and highly TO SELF-SUFFICIENCY urbanised Singapore, the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated our efforts to Singapore’s journey to food security safeguard food security, by harnessing technology and through partnerships has roots in partnerships, as with other countries to ensure that food supply chains are not disrupted Experience Singapore discovers (read our In Singapore feature on pages 8-9 to find out more). -

Updated Advisory for Safe Management Measures at F&B

JOINT ADVISORY MR No.: 045/21 Updated as of 12 July 2021 Updated Advisory for Safe Management Measures at Food & Beverage Establishments 1. The Multi-Ministry Taskforce (MTF) announced a gradual reopening in Phase 3 (Heightened Alert) starting with Stage 1 on 14 June and Stage 2 on 21 June 2021. In line with this, from 12 July 2021, activities such as dining-in at F&B establishments will be allowed to resume in group sizes of up to 5 persons. 2. To provide a safe environment for customers and workers, food and beverage (F&B) establishments currently in operation must implement Safe Management Measures (SMMs), as required by the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) and comply with the COVID- 19 (Temporary Measures) (Control Order) Regulations. 3. In addition, F&B establishments are required to comply with the measures set out by Enterprise Singapore (ESG), Housing & Development Board (HDB), Singapore Food Agency (SFA), Singapore Tourism Board (STB) and Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) in this document. The information in this document supersedes that in previous advisories or statements. Latest updates for F&B establishments 4. F&B establishments are allowed to resume food service operations, with the exception of establishments with Pubs, Bars, Nightclubs, Discos and Karaoke SFA license categories or SSIC codes starting with 5613. They must comply with the following: 4.1. From 12 July 2021, F&B establishments are permitted to seat dining groups of up to 5 persons (refer to Annex A for the infographic on SMMs). 4.2. Sale and consumption of alcohol in all F&B establishments are prohibited after 2230hrs daily1 . -

The Food and Beverage Market Entry Handbook: Singapore

1 | Page Singapore – Market Entry Handbook The Food and Beverage Market Entry Handbook: Singapore: a Practical Guide to the Market in Singapore for European Agri-food Products 2 | Page Singapore – Market Entry Handbook Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). This document has been prepared for the Consumers, Health, Agriculture and Food Executive Agency (Chafea) acting under the mandate from the European Commission. It reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission / Chafea cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. Euromonitor International Passport Data Disclaimer While every attempt has been made to ensure accuracy and reliability, Euromonitor International cannot be held responsible for omissions or errors of historic figures or analyses. While every attempt has been made to ensure accuracy and reliability, Agra CEAS cannot be held responsible for omissions or errors in the figures or analyses provided and cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. Note: the term EU in this handbook refers to the EU-27 excluding the UK, unless otherwise specified. For product trade stats, data is presented in order of exporter size for reasons of readability. Data for the UK is presented separately where it represents a notable origin (>5% of imports). In case it represents a negligible origin that would not be visually identifiable in a graph, data for the UK is incorporated under “rest of the world”. -

Sfa-And-Avs-Media-Release-(Final).Pdf

NEW SINGAPORE FOOD AGENCY TO OVERSEE FOOD SAFETY AND SECURITY THE NATIONAL PARKS BOARD TO OVERSEE ANIMAL AND WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT, AS WELL AS ANIMAL AND PLANT HEALTH Consolidation of functions and integration of expertise will enhance service delivery and deepen capabilities The Singapore Food Agency (SFA), a new statutory board, will be formed under the Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources (MEWR) to oversee food safety and security. SFA will bring together food-related functions currently carried out by the Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority of Singapore (AVA), the National Environment Agency (NEA) and the Health Sciences Authority (HSA). The integration will enhance regulatory oversight over all food related matters from farm to fork and further strengthen our food safety regime. It will facilitate better partnership with food businesses to develop new capabilities and solutions, and seize future opportunities. SFA will also provide better services to Singaporeans and businesses by harmonising regulations across the three agencies. 2 In parallel, all non-food plant and animal related functions of AVA will be transferred to the National Parks Board (NParks) under the Ministry of National Development (MND). NParks will become the lead agency for animal and wildlife management, as well as animal and plant health, and will work closely with the community and other stakeholders to enhance Singapore’s positioning as a City in a Garden. 3 Mr Lim Kok Thai, Chief Executive Officer of AVA, will be concurrently appointed as the Chief Executive Officer (Designate) of SFA. 1 Lead Agency to Develop Food Supply and Industry – “From Farm to Fork” 4 As the lead agency for food-related matters, SFA will partner food businesses to strengthen capabilities, tap on technologies to raise productivity, undertake research to develop new lines of business, and catalyse industry transformation. -

Singapore Food Agency Act 2019 (No

Singapore Food Agency Act 2019 (No. 11 of 2019) Table of Contents Long Title Enacting Formula Part 1 PRELIMINARY 1 Short title and commencement 2 Interpretation Part 2 ESTABLISHMENT, FUNCTIONS AND POWERS OF AGENCY 3 Singapore Food Agency 4 Agency is body corporate 5 Functions of Agency 6 Powers of Agency 7 Directions of Minister, etc. 8 Agency’s symbol, etc. Part 3 CONSTITUTION AND MEMBERSHIP OF AGENCY Division 1 — Appointment, resignation and removal 9 Membership of Agency 10 Appointment of Agency members Singapore Statutes Online Published in Acts Supplement on 18 Mar 2019 PDF created date on: 15 May 2019 11 Membership disqualification 12 Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson 13 Premature vacancies 14 Acting Chairperson and members 15 Removal of member 16 Resignation from office 17 Validity of acts, etc. Division 2 — Terms and conditions for members 18 Term of appointment 19 Remuneration, etc. 20 Vacation of office Part 4 DECISION-MAKING BY AGENCY Division 1 — Meetings 21 Procedure generally 22 Notice of meetings 23 Quorum 24 Presiding at meetings 25 Voting at meetings 26 Execution of documents Division 2 — Committees and delegation Singapore Statutes Online Published in Acts Supplement on 18 Mar 2019 PDF created date on: 15 May 2019 27 Appointment of committees 28 Proceedings of committees 29 Ability to delegate, etc. 30 Power of delegate, etc. Part 5 PERSONNEL MATTERS 31 Appointment of Chief Executive 32 Officers, etc. 33 Public servants 34 Preservation of secrecy 35 Protection from personal liability Part 6 FINANCIAL PROVISIONS 36 Financial year 37 Revenue and property of Agency 38 Bank accounts 39 Financial accounts and records 40 Power of investment 41 Issue of shares, etc. -

Your Support Matters

YOUR SUPPORT MATTERS MINDEFdoesnotendorseorrecommendorganisationswhichareawarded theNS Mark status and is innoway associatedwithsuch organisationsorany oftheirproducts,servicesoractivities. 2021 . AAS @ 217 EAST COAST ROAD PTE LTD . BRAND FINANCE CONSULTANCY (S) PTE LTD . AAS ACADEMY PTE LTD . BUILDING AND CONSTRUCTION . AAS INSURANCE AGENCY PTE LTD AUTHORITY . ADVENTURE 21 OUTDOOR & TRAVEL . CASINO REGULATORY AUTHORITY OUTFITTERS PTE LTD . CEN TECH PTE LTD . AJ2 HOLDINGS PTE LTD . CHIJ ST NICHOLAS GIRLS' SCHOOL . AUTOMOBILE ASSOCIATION OF (SEC) SINGAPORE . CITY DEVELOPMENTS LTD . AUTOSWIFT RECOVERY PTE LTD . DANOVEL PTE LTD . AV ONE FM & ENGINEERING PTE LTD . DECLARATORS PTE LTD . BLACK DOT PTE LTD . DEFENCE SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY . HOUSING & DEVELOPMENT BOARD AGENCY (DSTA) . HUBER'S PTE LTD . ECOXPLORE PTE LTD . IEG OILFIELD SERVICES PTE LTD . ELC PTE LTD . INFOLOGIC PTE LTD . ELXR PTE LTD . INSTITUTE OF TECHNICAL . ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT EDUCATION ASSOCIATION OF SINGAPORE . IRAS . ERECT GROUP (SINGAPORE) PTE LTD . MONETARY AUTHORITY OF . EVERGREEN SECONDARY SCHOOL SINGAPORE . FORCE-ONE SECURITY PTE LTD . NAN CHIAU HIGH SCHOOL . GUANGYANG PRIMARY SCHOOL . NATIONAL ARTS COUNCIL . NAUMI HOTELS SG PTE LTD . SANTE CRANE & EQUIPMENT PTE LTD . NEW ZEALAND DEFENCE SUPPORT UNIT . SANTE MACHINERY PTE LTD (NZDSU) SOUTH EAST ASIA (S.E.A) . SANTE SCAFFOLDING PTE LTD . PENANSHIN AIR EXPRESS PTE LTD . SECOM (SINGAPORE) PTE LTD . PICTURE PERFECT PRODUCTIONS PTE LTD . SEE HAI TAT MEDICAL HALL . QUANTEDGE CAPITAL PTE. LTD. (SINGAPORE) PTE LTD . ROYAL INSIGNIA PTE LTD . SINGAPORE AIRLINES LTD . SAF YACHT CLUB . SINGAPORE DISCOVERY CENTRE LTD . SAFRA NATIONAL SERVICE ASSOCIATION . SINGAPORE PRECISION ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY ASSOCIATION . SANTE ACCESS SYSTEM PTE LTD (SPETA) . SINGAPORE SEMICONDUCTOR INDUSTRY . WEARVR.ONE PTE LTD ASSOCIATION . SKYVENTURE VWT SINGAPORE PTE. LTD. SLIM STOCK ASIA PACIFIC PTE LTD . -

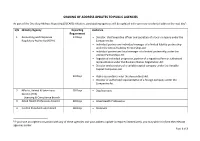

Sharing of Address Updates to Public Agencies

SHARING OF ADDRESS UPDATES TO PUBLIC AGENCIES As part of the One Stop Address Reporting (OSCARS) initiative, participating agencies will be updated with your new residential address the next day1: S/N Ministry/Agency Reporting Audience Requirement 1 Accounting and Corporate 14 Days Director, chief executive officer and secretary of a local company under the Regulatory Authority (ACRA) Companies Act Individual partner and individual manager of a limited liability partnership under the Limited Liability Partnerships Act Individual partner and local manager of a limited partnership under the Limited Partnerships Act Registered individual proprietor, partner of a registered firm or authorised representative under the Business Names Registration Act Director and secretary of a variable capital company under the Variable Capital Companies Act 30 Days Public accountant under the Accountants Act Director or authorised representative of a foreign company under the Companies Act 2 NParks, Animal & Veterinary 28 Days Dog licensees Service (AVS) – Licensing & Compliance branch 3 Allied Health Professions Council 28 Days Allied Health Professions 4 Central Provident Fund Board 28 Days Members 1If you have an urgent transaction with any of these agencies and your address update is required immediately, you may wish to inform the relevant agencies earlier. Page 1 of 3 5 Energy Market Authority 7 Days Licensed gas service workers 6 Housing and Development Board 28 Days Registrants for residential flats & tenants of non-residential premises -

Singapore Food and Agricultural Import Regulations and Standards

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Required Report - public distribution Date: 1/30/2019 GAIN Report Number: SN9003 Singapore Food and Agricultural Import Regulations and Standards Report FAIRS Annual Country Report 2018 Approved By: William Verzani, Agricultural Attaché Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei and Papua New Guinea Prepared By: Ira Sugita, Agricultural Specialist Report Highlights: This report provides information on the regulations and procedures for the importation of food and agricultural products from the United States to Singapore. Although the Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority (AVA) is currently the national body responsible for implementing food regulations in the country, a new government agency called the Singapore Food Agency (SFA) is scheduled to take over food-related regulatory responsibilities in April 2019. Updates in this report include modifications to the Singapore Food Regulations (guidelines governing imported food) and details on the Sale of Food Act of 2017, which came into operation on February 1, 2018. Table of Contents SECTION I. GENERAL FOOD LAWS ........................................................................................ 3 SECTION II: FOOD ADDITIVE REGULATIONS ...................................................................... 6 SECTION III: PESTICIDES AND OTHER CONTAMINANTS ................................................. 8 SECTION IV: PACKAGING AND CONTAINER REQUIREMENTS ...................................... -

Updated Advisory for Safe Management Measures at Food & Beverage Establishments Published: 12 August 2021

Updated Advisory for Safe Management Measures at Food & Beverage Establishments Published: 12 August 2021 Who Should Know: Mall developers, building owners, food & beverage business owners Effective Date: 10 August 2021 1. The Multi-Ministry Taskforce (MTF) has announced a calibrated path for resumption of more economic and social activities under Phase 2 (Heightened Alert) from 10 August 2021. Current Safe Management Measures (SMMs) will be adjusted as we transit to the endemic state. 2. To provide a safe environment for customers and workers, food and beverage (F&B) establishments currently in operation must implement Safe Management Measures (SMMs), as required by the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) and comply with the COVID-19 (Temporary Measures) (Control Order) Regulations. 3. In addition, F&B establishments are required to comply with the measures set out by Enterprise Singapore (ESG), Housing & Development Board (HDB), Singapore Food Agency (SFA), Singapore Tourism Board (STB) and Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) in this document. The information in this document supersedes that in previous advisories or statements. Page 1 of 15 Latest updates for F&B establishments 4. F&B establishments are allowed to continue food service operations, with the exception of establishments with Pubs, Bars, Nightclubs, Discos and Karaoke SFA license categories or SSIC codes starting with 5613. F&B establishments that are allowed to operate must comply with the following: Vaccinated-differentiated SMMs a. From 10 August 2021, F&B establishments are