Copyrighted Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boso's- Lfe of Alexdnder 111

Boso's- Lfe of Alexdnder 111 Introduction by PETER MUNZ Translated by G. M. ELLIS (AG- OXFORD . BASIL BLACKWELL @ Basil Blackwell 1973 AI1 rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval System, or uansmitted, in any form or by. any. means, electronic, mechanical, photo- copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permis- sion of Basil Blackwell & Mott Limited. ICBN o 631 14990 2 Library of Congress Catalog Card Num'cer: 72-96427 Printed in Great Britain by Western Printing Services Ltd, Bristol MONUMENTA GERilAANIAE I-' 11.2' I d8-:;c,-q-- Bibliothek Boso's history of Pope Alexander I11 (1159-1181) is the most re- markable Part of the Liber Pontificalis. Unlike almost all the other contributions, it is far more than an informative chronicle. It is a work of history in its own right and falsely described as a Life of Alexander 111. Boso's work is in fact a history of the Iong schism in the church brought about by the double election of I159 and perpet- uated until the Peace of Venice in I 177. It makes no claim to be a Life of Alexander because it not only says nothing about his career before his election but also purposely omits all those events and activities of his pontificate which do not strictly belong to the history of the schism. It ends with Alexander's return to Rome in 1176. Some historians have imagined that this ending was enforced by Boso's death which is supposed to have taken piace in 1178.~But there is no need for such a supposition. -

11. STRATIGRAFIA E RESTAURI AL BROLETTO DI BRESCIA.Pdf

ARCHEOLOGIA DELL’ARCHITETTURA Supplemento di «Archeologia Medievale» diretta da Gian Pietro Brogiolo e Sauro Gelichi (responsabile) Comitato di direzione: Segreteria di redazione: GIAN PIETRO BROGIOLO Lea Frosini FRANCESCO DOGLIONI c/o Edizioni All’Insegna del Giglio s.a.s. ROBERTO PARENTI e-mail [email protected] GIANFRANCO PERTOT Edizione e distribuzione: Redazione: ALL’INSEGNA DEL GIGLIO s.a.s. GIOVANNA BIANCHI via della Fangosa, 38; 50032 Borgo San Lorenzo (FI) ANNA BOATO tel. +39 055 8450216 fax +39 055 8453188 web site www.edigiglio.it e-mail [email protected]; ANNA DECRI [email protected] FABIO GABBRIELLI PRISCA GIOVANNINI Abbonamenti: ALESSANDRA QUENDOLO GIAN PAOLO TRECCANI «Archeologia dell’Architettura»: € 28,00 «Archeologia dell’Architettura» + volume annuale RITA VECCHIATTINI «Archeologia Medievale»: € 70,00 Per gli invii in contrassegno o all’estero saranno addebitate le Coordinamento di redazione: spese postali. Giovanna Bianchi – [email protected] I dati forniti dai sottoscrittori degli abbonamenti vengono Anna Boato – [email protected] utilizzati esclusivamente per l’invio della pubblicazione e non Alessandra Quendolo – [email protected] vengono ceduti a terzi per alcun motivo. ARCHEOLOGIA DELL’ARCHITETTURA XIV 2009 All’Insegna del Giglio ISSN 1126-6236 ISBN 978-88-7814-433-0 © 2011 All’Insegna del Giglio s.a.s. Stampato a Firenze nel dicembre 2011 Nuova Grafica Fiorentina s.r.l. Edizioni All’Insegna del Giglio s.a.s via della Fangosa, 38; 50032 Borgo S. Lorenzo (FI) tel. +39 055 8450 216; fax +39 055 8453 188 e-mail [email protected]; [email protected] sito web www.edigiglio.it INDICE I. ASPETTI TEORICO-METODOLOGICI E LAVORI DI SINTESI 9 M. -

Different Faces of One ‘Idea’ Jean-Yves Blaise, Iwona Dudek

Different faces of one ‘idea’ Jean-Yves Blaise, Iwona Dudek To cite this version: Jean-Yves Blaise, Iwona Dudek. Different faces of one ‘idea’. Architectural transformations on the Market Square in Krakow. A systematic visual catalogue, AFM Publishing House / Oficyna Wydawnicza AFM, 2016, 978-83-65208-47-7. halshs-01951624 HAL Id: halshs-01951624 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01951624 Submitted on 20 Dec 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Architectural transformations on the Market Square in Krakow A systematic visual catalogue Jean-Yves BLAISE Iwona DUDEK Different faces of one ‘idea’ Section three, presents a selection of analogous examples (European public use and commercial buildings) so as to help the reader weigh to which extent the layout of Krakow’s marketplace, as well as its architectures, can be related to other sites. Market Square in Krakow is paradoxically at the same time a typical example of medieval marketplace and a unique site. But the frontline between what is common and what is unique can be seen as “somewhat fuzzy”. Among these examples readers should observe a number of unexpected similarities, as well as sharp contrasts in terms of form, usage and layout of buildings. -

Blessed Giovanni Cacciafronte De Sordi with the Vicenza Mode

anticSwiss 28/09/2021 06:49:50 http://www.anticswiss.com Blessed Giovanni Cacciafronte de Sordi with the Vicenza mode FOR SALE ANTIQUE DEALER Period: 16° secolo - 1500 Ars Antiqua srl Milano Style: Altri stili +39 02 29529057 393664680856 Height:51cm Width:40.5cm Material:Olio su tela Price:3400€ DETAILED DESCRIPTION: 16th century Blessed Giovanni Cacciafronte de Sordi with the model of the city of Vicenza Oil on oval canvas, 51 x 40.5 cm The oval canvas depicts a holy bishop, as indicated by the attributes of the miter on the head of the young man and the crosier held by angel behind him. The facial features reflect those of a beardless young man, with a full and jovial face, corresponding to a youthful depiction of the blessed Giovanni Cacciafronte (Cremona, c. 1125 - Vicenza, March 16, 1181). Another characteristic attribute is the model of the city of Vicenza that he holds in his hands, the one of which he became bishop in 1175. Giovanni Cacciafronte de Sordi lived at the time of the struggle undertaken by the emperor Frederick Barbarossa (1125-1190), against the Papacy and the Italian Municipalities. Giovanni was born in Cremona around 1125 from a family of noble origins; still at an early age he lost his father, his mother remarried the noble Adamo Cacciafronte, who loved him as his own son, giving him his name; he received religious and cultural training. At sixteen he entered the Abbey of San Lorenzo in Cremona as a Benedictine monk; over the years his qualities and virtues became more and more evident, and he won the sympathies of his superiors and confreres. -

Manufacturing Middle Ages

Manufacturing Middle Ages Entangled History of Medievalism in Nineteenth-Century Europe Edited by Patrick J. Geary and Gábor Klaniczay LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 © 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978-90-04-24486-3 CONTENTS List of Figures ................................................................................................... ix Acknowledgements ........................................................................................ xiii Introduction ..................................................................................................... 1 PART ONE MEDIEVALISM IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY HISTORIOGRAPHY National Origin Narratives in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy ..... 13 Walter Pohl The Uses and Abuses of the Barbarian Invasions in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries ......................................................................... 51 Ian N. Wood Oehlenschlaeger and Ibsen: National Revival in Drama and History in Denmark and Norway c. 1800–1860 ................................. 71 Sverre Bagge Romantic Historiography as a Sociology of Liberty: Joachim Lelewel and His Contemporaries ......................................... 89 Maciej Janowski PART TWO MEDIEVALISM IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY ARCHITECTURE The Roots of Medievalism in North-West Europe: National Romanticism, Architecture, Literature .............................. 111 David M. Wilson Medieval and Neo-Medieval Buildings in Scandinavia ....................... 139 Anders Andrén © 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978-90-04-24486-3 vi contents Restoration as an Expression -

Milan and the Lakes Travel Guide

MILAN AND THE LAKES TRAVEL GUIDE Made by dk. 04. November 2009 PERSONAL GUIDES POWERED BY traveldk.com 1 Top 10 Attractions Milan and the Lakes Travel Guide Leonardo’s Last Supper The Last Supper , Leonardo da Vinci’s 1495–7 masterpiece, is a touchstone of Renaissance painting. Since the day it was finished, art students have journeyed to Milan to view the work, which takes up a refectory wall in a Dominican convent next to the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie. The 20th-century writer Aldous Huxley called it “the saddest work of art in the world”: he was referring not to the impact of the scene – the moment when Christ tells his disciples “one of you will betray me” – but to the fresco’s state of deterioration. More on Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) Crucifixion on Opposite Wall Top 10 Features 9 Most people spend so much time gazing at the Last Groupings Supper that they never notice the 1495 fresco by Donato 1 Leonardo was at the time studying the effects of Montorfano on the opposite wall, still rich with colour sound and physical waves. The groups of figures reflect and vivid detail. the triangular Trinity concept (with Jesus at the centre) as well as the effect of a metaphysical shock wave, Example of Ageing emanating out from Jesus and reflecting back from the 10 Montorfano’s Crucifixion was painted in true buon walls as he reveals there is a traitor in their midst. fresco , but the now barely visible kneeling figures to the sides were added later on dry plaster – the same method “Halo” of Jesus Leonardo used. -

History Italy (18151871) and Germany (18151890) 2Nd Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

HISTORY ITALY (18151871) AND GERMANY (18151890) 2ND EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Michael Wells | 9781316503638 | | | | | History Italy (18151871) and Germany (18151890) 2nd edition PDF Book This is a good introduction, as it shows a clear grasp of the topic, and sets out a logical plan that is clearly focused on the demands of the question. Activities throughout the chapters to encourage an exploratory and inquiring approach to historical learning. Jacqueline Paris. In , Italy forced Albania to become a de facto protectorate. Written by an experienced, practising IB English teacher, it covers key concepts in language and literature studies in a lively and engaging way suited to IB students aged 16— The Fascist regime engaged in interventionist foreign policy in Europe. Would you like to change to the site? Bosworth says of his foreign policy that Crispi:. He wanted to re-establish links with the papacy and was hostile to Garibaldi. Assessment Italy had become one of the great powers — it had acquired colonies; it had important allies; it was deeply involved in the diplomatic life of Europe. You are currently using the site but have requested a page in the site. However, there were some signs that Italy was developing a greater national identity. The mining and commerce of metal, especially copper and iron, led to an enrichment of the Etruscans and to the expansion of their influence in the Italian peninsula and the western Mediterranean sea. Retrieved 21 March Ma per me ce la stiamo cavando bene". Urbano Rattazzi —73 : Rattazzi was a lawyer from Piedmont. PL E Silvio writes: Italy was deeply divided by This situation was shaken in , when the French Army of Italy under Napoleon invaded Italy, with the aims of forcing the First Coalition to abandon Sardinia where they had created an anti-revolutionary puppet-ruler and forcing Austria to withdraw from Italy. -

Emperor Submitted to His Rebellious Subjects

Edinburgh Research Explorer When the emperor submitted to his rebellious subjects Citation for published version: Raccagni, G 2016, 'When the emperor submitted to his rebellious subjects: A neglected and innovative legal account of the 1183-Peace of Constance', English Historical Review, vol. 131, no. 550, pp. 519-39. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehr/cew173 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1093/ehr/cew173 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: English Historical Review Publisher Rights Statement: This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced version of an article accepted for publication in The English Historical Review following peer review. The version of record [Gianluca Raccagni, When the Emperor Submitted to his Rebellious Subjects: A Neglected and Innovative Legal Account of the Peace of Constance, 1183 , The English Historical Review, Volume 131, Issue 550, June 2016, Pages 519–539,] is available online at: https://doi.org/10.1093/ehr/cew173 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. -

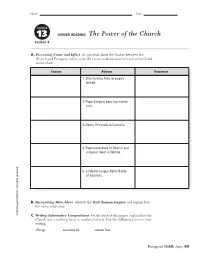

GUIDED READING the Power of the Church Section 4

wh10a-IDR-0313_P4 11/24/2003 4:05 PM Page 69 Name Date CHAPTER 13 GUIDED READING The Power of the Church Section 4 A. Perceiving Cause and Effect As you read about the clashes between the Church and European rulers, note the causes and outcomes of each action listed in the chart. Causes Actions Outcomes 1. Otto invades Italy on pope’s behalf. 2. Pope Gregory bans lay investi- ture. 3. Henry IV travels to Canossa. 4. Representatives of Church and emperor meet in Worms. 5. Lombard League fights Battle of Legnano. B. Recognizing Main Ideas Identify the Holy Roman Empire and explain how the name originated. cDougal Littell Inc. All rights reserved. ©M C. Writing Informative Compositions On the back of this paper, explain how the Church was a unifying force in medieval society. Use the following terms in your writing. clergy sacrament canon law European Middle Ages 69 wh10a-IDR-0313_P7 11/24/2003 4:06 PM Page 72 Name Date CHAPTER GEOGRAPHY APPLICATION: PLACE 13 Feudal Europe’s Religious Influences Section 4 Directions: Read the paragraphs below and study the map carefully. Then answer the questions that follow. he influence of the Latin Church—the Roman as did that of Hungary around 986. Large sections TCatholic Church—grew in western Europe of Scandinavia adopted the Latin Church by 1000. after 800. By 1000, at the end of the age of inva- In the fifth century, Ireland became the “island of sions, the Church’s vision of a spiritual kingdom in saints.” Then, between 500 and 900, Ireland helped feudal Europe was nearly realized. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-76039-3 — A Concise History of Italy Christopher Duggan Excerpt More Information Introduction In the late spring of 1860 Giuseppe Garibaldi, a flamboyant irregular soldier, who had spent much of his life abroad fighting as a guerrilla leader, set sail for Sicily from a port near Genoa. On board his two small ships was a motley collection of students and adventurers, many of them barely out of their teens. Their mission was to unify Italy. The prospects for success seemed limited: the group was ill-armed, and few among them had any experience in warfare or administration. Moreover, they did not constitute a promising advertisement for the nation-to-be. Among the thousand or so volunteers were Hungarians and Poles, and the Italian contingent included a disproportionate number from the small northern city of Bergamo. However, in the space of a few months they succeeded in conquering Sicily and the mainland South from the Bourbons; and in March 1861 Victor Emmanuel II, King of Piedmont–Sardinia, became the first king of united Italy. The success of Garibaldi and his ‘Thousand’ was both remarkable and unexpected; and when the euphoria had died down, many sober observers wondered whether the Italian state could survive. France and Austria, the two greatest continental powers of the day, both threatened to invade the new kingdom, break it up, and reconstitute the Papal States, which had been annexed by Victor Emmanuel in the course of unification. A much more insidious long-term threat, however, to the survival of the new state, was the absence of any real sense of commitment or loyalty to the kingdom among all except a small minority of the population. -

Seconde Lezioni Selvatico

MONZA 44 d.C. – 1444 - UOMINI, ARCHITETTURE, DIADEMI IL DUOMO ANTECEDENTE ALL’ATTUALE – al tempo di Federico II, dei Torriani e dei Visconti. Federico II, imperatore del sacro romano impero (1194–1250) manifesta le proprie mire sul controllo dell’Italia. Nel nord risorge la Lega Lombarda e a Milano nel 1228, in previsione di un attacco imperiale di Federico, si rinforzano in più punti le mura, si crea la Società Dei Forti per la custodia del carroccio con a capo Enrico Da Monza. Nella diatriba fra papa e imperatore intanto si sono inserite le città della Lega Lombarda e riprende la secolare divisione fra guelfi e ghibellini. Nel 1231 Federico convoca una dieta a Ravenna dalla quale riafferma l'autorità imperiale sui comuni, ma ciò non ha alcuna influenza sugli eventi successivi. La Chiesa è minacciata da tempo dai movimenti eretici. Nel 1231 l’imperatore germanico firma la “Constitutio Haereticos Lombardiae “, che prevede il rogo per gli eretici e il taglio della lingua per i bestemmiatori. In sede locale l’arciprete Leone da Perego (Ministro Francescano Provinciale della Lombardia) nel 1233 pubblica una serie di statuti contro le sette di eretici, ordinando al Podestà di arruolare guardie per la ricerca e l’arresto degli eretici, a spese della comunità. La principale setta eretica del tempo sono i Catari. Essi intendono tornare al modello ideale di chiesa descritto nei Vangeli e negli Atti Degli Apostoli. Si auto definiscono Catari o «Uomini Puri». in genere vengono chiamati in modi diversi, prendendo il nome dal luogo in cui vivono: albigesi da Albi, concorezziani da Concorezzo, ecc. -

Andrea Gastaldi Turin, 1826 - 1889

Andrea Gastaldi Turin, 1826 - 1889 Study for the Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa escaping from the battlefield in Legnano 1858 Charcoal, with white highlights, on light brown paper 163 x 127 cm. Provenance: The artist’s studio upon his death in 1889; and by descent until acquired by the father of the previous owner in the 1970s Comparative literature: M. Ranzi, Les Beaux-arts italiens à l'exposition universelle de Paris, Paris, 1867 G. Lavivi, Andrea Gastaldi, studio critico, in “Gazzetta letteraria artistica scientifica”, XV, Torino, 1891, p. 286 U. Thieme & F. Becker, Kunstlerlexikon̈ , XIII, p. 240 A. Comandini, L’Italia nei cento anni del secolo XIX (1801-1900) giorno per giorno illustrata, vol. 3, Milano, 1918 A. M. Brizio, in Enciclopedia Italiana, XVI, Roma, 1932 R. Maggio Serra, Andrea Gastaldi (1826/1889). Un pittore a Torino tra romanticismo e realismo, Torino, 1988 E. Dellapiana, Gli Accademici dell’Albertina (Torino 1823-1884), Torino, 2002 This exceptional and impressive charcoal drawing is part of a series of rare, life-size studies, by Andrea Gastaldi, who was one of the preeminent Academy painters and leading proponents of historical romanticism in 19th century Italy. The drawings are outstanding not only for their impressive size and the virtuosity of their execution, but also for their remarkable historical significance. The present cartone was made in 1858 - a key moment in the artist’s career, after a crucial period spent in Paris. It was also the same year that he was elected Professor at the Accademia Albertina in Turin. Gastaldi held this influential position for 30 years and had a great impact on subsequent generations of Piedmontese painters.