Biogeography and Pattern Variation of Kingsnakes, Lampropeltis Getula, in the Apalachicola Region of Florida

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TPWD White List

TPWD White List Frogs and Toads Great Plains toad (Bufo cognatus) Green toad (Bufo debilis) Red-spotted toad (Bufo punctatus) Texas toad (Bufo speciosus) Gulf Coast toad (Bufo valliceps) Woodhouse’s toad (Bufo woodhousei) Green treefrog (Hyla cinerea) Bull frog (Rana catesbeiana) Couch’s spadefoot (Scaphiopus couchii) Plains spadefoot (Spea bombifrons) New Mexico spadefoot (Spea multiplicata) Salamanders Tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum) Lizards Green anole (Anolis carolinensis) Chihuahuan spotted whiptail (Aspidoscelis exsanguis) Texas spotted whiptail (Aspidoscelis gularis) Marbled whiptail (Aspidoscelis marmoratus) Six-lined racerunner (Aspidoscelis sexlineatus) Checkered whiptail (Aspidoscelis tesselatus) Texas banded gecko (Coleonyx brevis) Greater earless lizard (Cophosaurus texanus) Collared lizard (Crotaphytus collaris) Five-lined skink (Eumeces fasciatus) Great plains skink (Eumeces obsoletus) Texas alligator lizard (Gerrhonotus infernalis) Lesser earless lizard (Holbrookia maculata) Crevice spiny lizard (Sceloporus poinsettii) Prairie lizard (Sceloporus undulatus) Ground skink (Scincella lateralis) Tree lizard (Urosaurus ornatus) Side-blotched lizard (Uta stansburiana) Snakes Copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix) Cottonmouth (Agkistrodon piscivorus) Glossy snake (Arizona elegans) Trans-Pecos rat snake (Bogertophis subocularis) Racer (Coluber constrictor) Western diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus atrox) Rock rattlesnake (Crotalus lepidus) Blacktail rattlesnake (Crotalus molossus) Mojave rattlesnake (Crotalus scutulatus) Prairie -

Snakes of the Everglades Agricultural Area1 Michelle L

CIR1462 Snakes of the Everglades Agricultural Area1 Michelle L. Casler, Elise V. Pearlstine, Frank J. Mazzotti, and Kenneth L. Krysko2 Background snakes are often escapees or are released deliberately and illegally by owners who can no longer care for them. Snakes are members of the vertebrate order Squamata However, there has been no documentation of these snakes (suborder Serpentes) and are most closely related to lizards breeding in the EAA (Tennant 1997). (suborder Sauria). All snakes are legless and have elongated trunks. They can be found in a variety of habitats and are able to climb trees; swim through streams, lakes, or oceans; Benefits of Snakes and move across sand or through leaf litter in a forest. Snakes are an important part of the environment and play Often secretive, they rely on scent rather than vision for a role in keeping the balance of nature. They aid in the social and predatory behaviors. A snake’s skull is highly control of rodents and invertebrates. Also, some snakes modified and has a great degree of flexibility, called cranial prey on other snakes. The Florida kingsnake (Lampropeltis kinesis, that allows it to swallow prey much larger than its getula floridana), for example, prefers snakes as prey and head. will even eat venomous species. Snakes also provide a food source for other animals such as birds and alligators. Of the 45 snake species (70 subspecies) that occur through- out Florida, 23 may be found in the Everglades Agricultural Snake Conservation Area (EAA). Of the 23, only four are venomous. The venomous species that may occur in the EAA are the coral Loss of habitat is the most significant problem facing many snake (Micrurus fulvius fulvius), Florida cottonmouth wildlife species in Florida, snakes included. -

Biological Resources and Management

Vermilion flycatcher The upper Muddy River is considered one of the Mojave’s most important Common buckeye on sunflower areas of biodiversity and regionally Coyote (Canis latrans) Damselfly (Enallagma sp.) (Junonia coenia on Helianthus annuus) important ecological but threatened riparian landscapes (Provencher et al. 2005). Not only does the Warm Springs Natural Area encompass the majority of Muddy River tributaries it is also the largest single tract of land in the upper Muddy River set aside for the benefit of native species in perpetuity. The prominence of water in an otherwise barren Mojave landscape provides an oasis for regional wildlife. A high bird diversity is attributed to an abundance of riparian and floodplain trees and shrubs. Contributions to plant diversity come from the Mojave Old World swallowtail (Papilio machaon) Desertsnow (Linanthus demissus) Lobe-leaved Phacelia (Phacelia crenulata) Cryptantha (Cryptantha sp.) vegetation that occur on the toe slopes of the Arrow Canyon Range from the west and the plant species occupying the floodplain where they are supported by a high water table. Several marshes and wet meadows add to the diversity of plants and animals. The thermal springs and tributaries host an abundance of aquatic species, many of which are endemic. The WSNA provides a haven for the abundant wildlife that resides permanently or seasonally and provides a significant level of protection for imperiled species. Tarantula (Aphonopelma spp.) Beavertail cactus (Opuntia basilaris) Pacific tree frog (Pseudacris regilla) -

Significant New Records of Amphibians and Reptiles from Georgia, USA

GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION 597 Herpetological Review, 2015, 46(4), 597–601. © 2015 by Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles Significant New Records of Amphibians and Reptiles from Georgia, USA Distributional maps found in Amphibians and Reptiles of records for a variety of amphibian and reptile species in Georgia. Georgia (Jensen et al. 2008), along with subsequent geographical All records below were verified by David Bechler (VSU), Nikole distribution notes published in Herpetological Review, serve Castleberry (GMNH), David Laurencio (AUM), Lance McBrayer as essential references for county-level occurrence data for (GSU), and David Steen (SRSU), and datum used was WGS84. herpetofauna in Georgia. Collectively, these resources aid Standard English names follow Crother (2012). biologists by helping to identify distributional gaps for which to target survey efforts. Herein we report newly documented county CAUDATA — SALAMANDERS DIRK J. STEVENSON AMBYSTOMA OPACUM (Marbled Salamander). CALHOUN CO.: CHRISTOPHER L. JENKINS 7.8 km W Leary (31.488749°N, 84.595917°W). 18 October 2014. D. KEVIN M. STOHLGREN Stevenson. GMNH 50875. LOWNDES CO.: Langdale Park, Valdosta The Orianne Society, 100 Phoenix Road, Athens, (30.878524°N, 83.317114°W). 3 April 1998. J. Evans. VSU C0015. Georgia 30605, USA First Georgia record for the Suwannee River drainage. MURRAY JOHN B. JENSEN* CO.: Conasauga Natural Area (34.845116°N, 84.848180°W). 12 Georgia Department of Natural Resources, 116 Rum November 2013. N. Klaus and C. Muise. GMNH 50548. Creek Drive, Forsyth, Georgia 31029, USA DAVID L. BECHLER Department of Biology, Valdosta State University, Valdosta, AMBYSTOMA TALPOIDEUM (Mole Salamander). BERRIEN CO.: Georgia 31602, USA St. -

Lampropeltis Getula Getula

Scholars Crossing Faculty Publications and Presentations Department of Biology and Chemistry 2005 Field Notes: Lampropeltis getula getula Timothy R. Brophy Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/bio_chem_fac_pubs Recommended Citation Brophy, Timothy R., "Field Notes: Lampropeltis getula getula" (2005). Faculty Publications and Presentations. 42. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/bio_chem_fac_pubs/42 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology and Chemistry at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. • CA TESBEIANA 2005, 25(2) basic natural history needs [for the herpetofauna of Virginia's Eastern Shore1 is the fact that we do not yet have a full understanding of the distributional patterns for any species." Accordingly, I report on a Field Notes vouchered record for Scincella lateralis from Accomack County. On II June 2001 at 2015 h, an adult little brown skink was found scurrying County Airport, Melfa, VA). The snake was not captured, but a color along the cement apron of the garage at 24326 Finney Drive. This photograph has been deposited in the VHS archives (voucher #68). residence is in close proximity to both Parkers Creek (ca. 10 m) and a large agricultural field (ca. 25 m). The skink was not captured, but a There are several other vouchered records for L. g. getula from Accomack color photograph has been deposited in the VHS archives (voucher #69). County (Mitchell, J.C. 1994. -

Lampropeltis Getula, in South Carolina

2007, No. 3 COPEIA September 10 Copeia, 2007(3), pp. 507–519 Enigmatic Decline of a Protected Population of Eastern Kingsnakes, Lampropeltis getula, in South Carolina CHRISTOPHER T. WINNE,JOHN D. WILLSON,BRIAN D. TODD,KIMBERLY M. ANDREWS, AND J. WHITFIELD GIBBONS Although recent reports of global amphibian declines have received considerable attention, reptile declines have gone largely unreported. Among reptiles, snakes are particularly difficult to quantitatively sample, and thus, most reports of snake declines are based on qualitative or anecdotal evidence. Recently, several sources have suggested that Eastern Kingsnakes (Lampropeltis getula) have declined over a substantial portion of their range in the southeastern United States, particularly in Florida. However, published evidence for L. getula declines or their potential causes are limited. We monitored the status of a population of L. getula on the U.S. Department of Energy’s Savannah River Site (SRS) in Aiken, South Carolina, USA, from 1975 to 2006. Herpetofaunal populations on the Savannah River Site have been protected from the pressures of collecting and development since 1951 due to site access restrictions. Here, we document a decline in both abundance and body condition of L. getula inhabiting the vicinity of a large isolated wetland over the past three decades. Because this L. getula population was protected from anthropogenic habitat degradation, collection, and road mortality, we are able to exclude these factors as possible causes of the documented decline. Although the definitive cause of the decline remains enigmatic, natural succession of the surrounding uplands, periodic extreme droughts, shifts in community composition (e.g., increased Agkistrodon piscivorus abundance), introduced fire ants, or disease are all potential contributors to the decline. -

Kingsnake Lampropeltis Getula, L

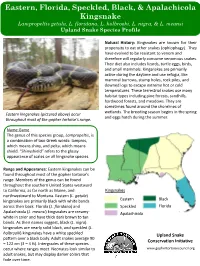

Eastern, Florida, Speckled, Black, & Apalachicola Kingsnake Lampropeltis getula, L. floridana, L. holbrooki, L. nigra, & L. meansi Upland Snake Species Profile Natural History: Kingsnakes are known for their propensity to eat other snakes (ophiophagy). They have evolved to be resistant to venom and therefore will regularly consume venomous snakes. Their diet also includes lizards, turtle eggs, birds, and small mammals. Kingsnakes are primarily active during the daytime and use refugia, like mammal burrows, stump holes, rock piles, and downed logs to escape extreme hot or cold temperatures. These terrestrial snakes use many habitat types including pine forests, sandhills, hardwood forests, and meadows. They are sometimes found around the shorelines of wetlands. The breeding season begins in the spring Eastern kingsnakes (pictured above) occur and eggs hatch during the summer. throughout most of the gopher tortoise’s range. Name Game The genus of this species group, Lampropeltis, is a combination of two Greek words: lampros, which means shiny, and pelta, which means shield. “Shinyshield” refers to the glossy appearance of scales on all kingsnake species. Range and Appearance: Eastern kingsnakes can be found throughout most of the gopher tortoise’s range. Members of the genus can be found throughout the southern United States westward to California, as far north as Maine, and Kingsnakes northwestward to Montana. Eastern (L. getula) kingsnakes are primarily black with white bands Eastern Black across their back. Florida (L. floridana) and Speckled Florida Apalachicola (L. meansi) kingsnakes are creamy- Apalachicola white in color and have thick dark brown to tan bands. As their names suggest, black (L. nigra) kingsnakes are nearly solid black, and speckled (L. -

Development and Assessment of a Wildlife Habitat Relationship Model for Terrestrial Vertebrates in the State of Maryland

DEVELOPMENT AND ASSESSMENT OF A WILDLIFE HABITAT RELATIONSHIP MODEL FOR TERRESTRIAL VERTEBRATES IN THE STATE OF MARYLAND by Robert John Northrop A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Wildlife Ecology Spring 2009 Copyright 2009 Robert John Northrop All Rights Reserved DEVELOPMENT AND ASSESSMENT OF A WILDLIFE HABITAT RELATIONSHIP MODEL FOR TERRESTRIAL VERTEBRATES IN THE STATE OF MARYLAND by Robert John Northrop Approved: __________________________________________________________ Jacob L. Bowman, Ph.D. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: __________________________________________________________ Douglas W. Tallamy, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology Approved: __________________________________________________________ Robin Morgan, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources Approved: __________________________________________________________ Debra Hess Norris, M.S. Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank Dr. Jacob Bowman for his patience and continuing support over the past several years. Thanks to Dr. Roland Roth who originally asked me to teach at the University of Delaware in 1989. The experience of teaching wildlife conservation and management at the University for 14 years has changed the way I approach my professional life as a forest ecologist. I also offer a big thank – you to all my students at the University I have learned more from you than you can imagine. I am grateful to the U.S. Forest Service, Dr. Mark Twery and Scott Thomasma, for funding the initial literature review and research, and for ongoing database support as we use this work to build a useful conservation tool for planners and natural resource managers in Maryland. -

Eastern Kingsnake Lampropeltis Getula ILLINOIS RANGE

eastern kingsnake Lampropeltis getula Kingdom: Animalia FEATURES Phylum: Chordata Two subspecies of this snake are found in Illinois: Class: Reptilia the black kingsnake and the speckled kingsnake. The Order: Squamata black kingsnake averages 36 to 45 inches in length. It has shiny, smooth scales. The head is a little wider Family: Colubridae than the neck. Its body is black above with small ILLINOIS STATUS white or yellow spots that may be in a somewhat chainlike pattern. Some individuals may be almost common, native pure black. The speckled kingsnake averages 36 to 48 inches in length. It has shiny, smooth scales. A white or yellow spot may be found centered in each of the black or dark-brown scales of the back. The spots may be close enough together to give the appearance of white bands across the back. BEHAVIORS The black kingsnake lives in dry, rocky hills, open woods, dry prairies and stream valleys. It is most often found under flat rocks, logs or when it is crossing roads. This snake kills prey by constriction. When disturbed, it will vibrate the tail rapidly, hiss and strike. Mating occurs in spring. The female deposits about 13 eggs in July. Eggs tend to stick together. Eggs hatch in late August or September. This snake will eat other snakes, lizards, rodents, small birds, bird eggs and turtle eggs. The speckled kingsnake lives in swamps, woods and stream ILLINOIS RANGE valleys, hiding under rocks, logs, ledges, vegetation and other objects. It is active in the day during spring and fall but becomes active at night in the heat of summer. -

Venomous Nonvenomous Snakes of Florida

Venomous and nonvenomous Snakes of Florida PHOTOGRAPHS BY KEVIN ENGE Top to bottom: Black swamp snake; Eastern garter snake; Eastern mud snake; Eastern kingsnake Florida is home to more snakes than any other state in the Southeast – 44 native species and three nonnative species. Since only six species are venomous, and two of those reside only in the northern part of the state, any snake you encounter will most likely be nonvenomous. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission MyFWC.com Florida has an abundance of wildlife, Snakes flick their forked tongues to “taste” their surroundings. The tongue of this yellow rat snake including a wide variety of reptiles. takes particles from the air into the Jacobson’s This state has more snakes than organs in the roof of its mouth for identification. any other state in the Southeast – 44 native species and three nonnative species. They are found in every Fhabitat from coastal mangroves and salt marshes to freshwater wetlands and dry uplands. Some species even thrive in residential areas. Anyone in Florida might see a snake wherever they live or travel. Many people are frightened of or repulsed by snakes because of super- stition or folklore. In reality, snakes play an interesting and vital role K in Florida’s complex ecology. Many ENNETH L. species help reduce the populations of rodents and other pests. K Since only six of Florida’s resident RYSKO snake species are venomous and two of them reside only in the northern and reflective and are frequently iri- part of the state, any snake you en- descent. -

Great Dismal Swamp Northern Brown Snake

Snakes Toads and Frogs Brown water snake................................Nerodia taxispilota Eastern spadefoot..............Scaphiopus holbrooki holbrooki U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Red-bellied water snake...................Nerodia erythrogaster American toad...........................................Bufo americanus erythrogaster Southern toad................................................Bufo terrestris Northern water snake...................Nerodia sipedon sipedon Fowler’s toad................................Bufo woodhousii fowleri Great Dismal Swamp Northern brown snake... ..................Storeria dekayi dekayi Oak toad.......................................................Bufo quercicus Northern red-bellied snake.........Storeria occipitomaculata Spring peeper........................................Pseudacris crucifer National Wildlife Refuge occipitamaculata Pinewoods tree frog......................................Hyla femoralis Eastern ribbon snake.............Thamnophis sauritus sauritus Squirrel tree frog...........................................Hyla squirella Eastern garter snake.................Thamnophis sirtalis sirtalis Gray tree frog..............................................Hyla versicolor Eastern earth snake.....................Virginia valeriae valeriae Little grass frog....................................Pseudacris ocularis Animals of the Eastern hognose snake...Heterodon platirhinos platirhinos Upland chorus frog..............Pseudacris triseriata feriarum Southern ringneck snake....Diadophis punctatus punctatus -

Dorsal and Ventral Color Patterns in a South Georgia Population of Agkistrodon Piscivorus Contanti, the Florida Cottonmouth David L

Georgia Journal of Science Volume 75 No. 2 Scholarly Contributions from the Article 13 Membership and Others 2017 Dorsal and Ventral Color Patterns in a South Georgia Population of Agkistrodon piscivorus contanti, the Florida Cottonmouth David L. Bechler Valdosta State University, [email protected] Joseph A. Kirkley Mr. Wiregrass Georgia Technical College, [email protected] John F. Elder Valdosta State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.gaacademy.org/gjs Part of the Life Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Bechler, David L.; Kirkley, Joseph A. Mr.; and Elder, John F. (2017) "Dorsal and Ventral Color Patterns in a South Georgia Population of Agkistrodon piscivorus contanti, the Florida Cottonmouth," Georgia Journal of Science, Vol. 75, No. 2, Article 13. Available at: http://digitalcommons.gaacademy.org/gjs/vol75/iss2/13 This Research Articles is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ the Georgia Academy of Science. It has been accepted for inclusion in Georgia Journal of Science by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ the Georgia Academy of Science. Dorsal and Ventral Color Patterns in a South Georgia Population of Agkistrodon piscivorus contanti, the Florida Cottonmouth Cover Page Footnote As the editor-in-chief of the Georgia Journal of Science, upon submission of this manuscript, I, David L. Bechler, have recused myself of all aspects of the review process and assigned the associate editor all aspects of the review process to include acceptance or rejection. This research articles is available in Georgia Journal of Science: http://digitalcommons.gaacademy.org/gjs/vol75/iss2/13 Bechler et al.: Dorsal and Ventral Agkistrodon piscivorus Coloring Patterns DORSAL AND VENTRAL COLOR PATTERNS IN A SOUTH GEORGIA POPULATION OF Agkistrodon piscivorus conanti, THE FLORIDA COTTONMOUTH 1David L.