Amphibians and Reptiles on Virginia's Eastern Shore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TPWD White List

TPWD White List Frogs and Toads Great Plains toad (Bufo cognatus) Green toad (Bufo debilis) Red-spotted toad (Bufo punctatus) Texas toad (Bufo speciosus) Gulf Coast toad (Bufo valliceps) Woodhouse’s toad (Bufo woodhousei) Green treefrog (Hyla cinerea) Bull frog (Rana catesbeiana) Couch’s spadefoot (Scaphiopus couchii) Plains spadefoot (Spea bombifrons) New Mexico spadefoot (Spea multiplicata) Salamanders Tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum) Lizards Green anole (Anolis carolinensis) Chihuahuan spotted whiptail (Aspidoscelis exsanguis) Texas spotted whiptail (Aspidoscelis gularis) Marbled whiptail (Aspidoscelis marmoratus) Six-lined racerunner (Aspidoscelis sexlineatus) Checkered whiptail (Aspidoscelis tesselatus) Texas banded gecko (Coleonyx brevis) Greater earless lizard (Cophosaurus texanus) Collared lizard (Crotaphytus collaris) Five-lined skink (Eumeces fasciatus) Great plains skink (Eumeces obsoletus) Texas alligator lizard (Gerrhonotus infernalis) Lesser earless lizard (Holbrookia maculata) Crevice spiny lizard (Sceloporus poinsettii) Prairie lizard (Sceloporus undulatus) Ground skink (Scincella lateralis) Tree lizard (Urosaurus ornatus) Side-blotched lizard (Uta stansburiana) Snakes Copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix) Cottonmouth (Agkistrodon piscivorus) Glossy snake (Arizona elegans) Trans-Pecos rat snake (Bogertophis subocularis) Racer (Coluber constrictor) Western diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus atrox) Rock rattlesnake (Crotalus lepidus) Blacktail rattlesnake (Crotalus molossus) Mojave rattlesnake (Crotalus scutulatus) Prairie -

Literature Cited Literature Cited

Literature Cited Literature Cited CCP - May 2004 LC-1 Literature Cited Adams, Matthew L. 1994. Assessment and Status of World War II Harbor Defense Structures. Submitted to Eastern Shore of Virginia National Wildlife Refuge, Cape Charles Virginia by Matthew L. Adams and Christopher K. Wiles, Ithaca, New York. Adams, Melissa, Julia Freedgood and Jennifer Phelan. May 1999. Cost of Community Service Study for Northampton County, Virginia. American Farmland Trust: Northampton, Mass. 14 pp. Askins, R.A. 1993. Population trends in grassland, shrubland, and forest birds in eastern North America. Pages 1-34 in D.M. Power, ed, Current Ornithology. Vol. 11 Plenum Publ. Corp. New York, NY. Bailey, R.G. 1995. Description of the Ecoregions of the United States. 2nd ed. rev. and expanded (1st ed. 1980). Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. Misc. Publ. No. 1391 (rev.), pp. 31-33. Berdeen, J. B. and D. G. Krementz. 1998. The use of fields at night by wintering American woodcock. Journal of Wildlife Management 62: 939-947. Blake, J.G., and W. G. Hoppes. 1986. Influence of resource abundance on use of tree-fall gaps by birds in an isolated woodlot. Auk 103:328-340. Breen, T.H. and Innes, S., 1980. “Myne Owne Ground:” Race and Freedom on Virginia’s Eastern Shore, 1640-1676. Oxford University Press, New York, p. 11. Brown, J. K. and J. K. Smith, eds. 2000. Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on flora. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 2. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Moun- tain Research Station. -

Snakes of the Everglades Agricultural Area1 Michelle L

CIR1462 Snakes of the Everglades Agricultural Area1 Michelle L. Casler, Elise V. Pearlstine, Frank J. Mazzotti, and Kenneth L. Krysko2 Background snakes are often escapees or are released deliberately and illegally by owners who can no longer care for them. Snakes are members of the vertebrate order Squamata However, there has been no documentation of these snakes (suborder Serpentes) and are most closely related to lizards breeding in the EAA (Tennant 1997). (suborder Sauria). All snakes are legless and have elongated trunks. They can be found in a variety of habitats and are able to climb trees; swim through streams, lakes, or oceans; Benefits of Snakes and move across sand or through leaf litter in a forest. Snakes are an important part of the environment and play Often secretive, they rely on scent rather than vision for a role in keeping the balance of nature. They aid in the social and predatory behaviors. A snake’s skull is highly control of rodents and invertebrates. Also, some snakes modified and has a great degree of flexibility, called cranial prey on other snakes. The Florida kingsnake (Lampropeltis kinesis, that allows it to swallow prey much larger than its getula floridana), for example, prefers snakes as prey and head. will even eat venomous species. Snakes also provide a food source for other animals such as birds and alligators. Of the 45 snake species (70 subspecies) that occur through- out Florida, 23 may be found in the Everglades Agricultural Snake Conservation Area (EAA). Of the 23, only four are venomous. The venomous species that may occur in the EAA are the coral Loss of habitat is the most significant problem facing many snake (Micrurus fulvius fulvius), Florida cottonmouth wildlife species in Florida, snakes included. -

Biological Resources and Management

Vermilion flycatcher The upper Muddy River is considered one of the Mojave’s most important Common buckeye on sunflower areas of biodiversity and regionally Coyote (Canis latrans) Damselfly (Enallagma sp.) (Junonia coenia on Helianthus annuus) important ecological but threatened riparian landscapes (Provencher et al. 2005). Not only does the Warm Springs Natural Area encompass the majority of Muddy River tributaries it is also the largest single tract of land in the upper Muddy River set aside for the benefit of native species in perpetuity. The prominence of water in an otherwise barren Mojave landscape provides an oasis for regional wildlife. A high bird diversity is attributed to an abundance of riparian and floodplain trees and shrubs. Contributions to plant diversity come from the Mojave Old World swallowtail (Papilio machaon) Desertsnow (Linanthus demissus) Lobe-leaved Phacelia (Phacelia crenulata) Cryptantha (Cryptantha sp.) vegetation that occur on the toe slopes of the Arrow Canyon Range from the west and the plant species occupying the floodplain where they are supported by a high water table. Several marshes and wet meadows add to the diversity of plants and animals. The thermal springs and tributaries host an abundance of aquatic species, many of which are endemic. The WSNA provides a haven for the abundant wildlife that resides permanently or seasonally and provides a significant level of protection for imperiled species. Tarantula (Aphonopelma spp.) Beavertail cactus (Opuntia basilaris) Pacific tree frog (Pseudacris regilla) -

Significant New Records of Amphibians and Reptiles from Georgia, USA

GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION 597 Herpetological Review, 2015, 46(4), 597–601. © 2015 by Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles Significant New Records of Amphibians and Reptiles from Georgia, USA Distributional maps found in Amphibians and Reptiles of records for a variety of amphibian and reptile species in Georgia. Georgia (Jensen et al. 2008), along with subsequent geographical All records below were verified by David Bechler (VSU), Nikole distribution notes published in Herpetological Review, serve Castleberry (GMNH), David Laurencio (AUM), Lance McBrayer as essential references for county-level occurrence data for (GSU), and David Steen (SRSU), and datum used was WGS84. herpetofauna in Georgia. Collectively, these resources aid Standard English names follow Crother (2012). biologists by helping to identify distributional gaps for which to target survey efforts. Herein we report newly documented county CAUDATA — SALAMANDERS DIRK J. STEVENSON AMBYSTOMA OPACUM (Marbled Salamander). CALHOUN CO.: CHRISTOPHER L. JENKINS 7.8 km W Leary (31.488749°N, 84.595917°W). 18 October 2014. D. KEVIN M. STOHLGREN Stevenson. GMNH 50875. LOWNDES CO.: Langdale Park, Valdosta The Orianne Society, 100 Phoenix Road, Athens, (30.878524°N, 83.317114°W). 3 April 1998. J. Evans. VSU C0015. Georgia 30605, USA First Georgia record for the Suwannee River drainage. MURRAY JOHN B. JENSEN* CO.: Conasauga Natural Area (34.845116°N, 84.848180°W). 12 Georgia Department of Natural Resources, 116 Rum November 2013. N. Klaus and C. Muise. GMNH 50548. Creek Drive, Forsyth, Georgia 31029, USA DAVID L. BECHLER Department of Biology, Valdosta State University, Valdosta, AMBYSTOMA TALPOIDEUM (Mole Salamander). BERRIEN CO.: Georgia 31602, USA St. -

Lampropeltis Getula Getula

Scholars Crossing Faculty Publications and Presentations Department of Biology and Chemistry 2005 Field Notes: Lampropeltis getula getula Timothy R. Brophy Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/bio_chem_fac_pubs Recommended Citation Brophy, Timothy R., "Field Notes: Lampropeltis getula getula" (2005). Faculty Publications and Presentations. 42. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/bio_chem_fac_pubs/42 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology and Chemistry at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. • CA TESBEIANA 2005, 25(2) basic natural history needs [for the herpetofauna of Virginia's Eastern Shore1 is the fact that we do not yet have a full understanding of the distributional patterns for any species." Accordingly, I report on a Field Notes vouchered record for Scincella lateralis from Accomack County. On II June 2001 at 2015 h, an adult little brown skink was found scurrying County Airport, Melfa, VA). The snake was not captured, but a color along the cement apron of the garage at 24326 Finney Drive. This photograph has been deposited in the VHS archives (voucher #68). residence is in close proximity to both Parkers Creek (ca. 10 m) and a large agricultural field (ca. 25 m). The skink was not captured, but a There are several other vouchered records for L. g. getula from Accomack color photograph has been deposited in the VHS archives (voucher #69). County (Mitchell, J.C. 1994. -

Lampropeltis Getula, in South Carolina

2007, No. 3 COPEIA September 10 Copeia, 2007(3), pp. 507–519 Enigmatic Decline of a Protected Population of Eastern Kingsnakes, Lampropeltis getula, in South Carolina CHRISTOPHER T. WINNE,JOHN D. WILLSON,BRIAN D. TODD,KIMBERLY M. ANDREWS, AND J. WHITFIELD GIBBONS Although recent reports of global amphibian declines have received considerable attention, reptile declines have gone largely unreported. Among reptiles, snakes are particularly difficult to quantitatively sample, and thus, most reports of snake declines are based on qualitative or anecdotal evidence. Recently, several sources have suggested that Eastern Kingsnakes (Lampropeltis getula) have declined over a substantial portion of their range in the southeastern United States, particularly in Florida. However, published evidence for L. getula declines or their potential causes are limited. We monitored the status of a population of L. getula on the U.S. Department of Energy’s Savannah River Site (SRS) in Aiken, South Carolina, USA, from 1975 to 2006. Herpetofaunal populations on the Savannah River Site have been protected from the pressures of collecting and development since 1951 due to site access restrictions. Here, we document a decline in both abundance and body condition of L. getula inhabiting the vicinity of a large isolated wetland over the past three decades. Because this L. getula population was protected from anthropogenic habitat degradation, collection, and road mortality, we are able to exclude these factors as possible causes of the documented decline. Although the definitive cause of the decline remains enigmatic, natural succession of the surrounding uplands, periodic extreme droughts, shifts in community composition (e.g., increased Agkistrodon piscivorus abundance), introduced fire ants, or disease are all potential contributors to the decline. -

Amphibians and Reptiles of Bankhead National Forest Hardwood Checklist Summer Winter Spring Pond

Habitats of Bankhead National Forest AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES OF Large Creek/River BANKHEAD NATIONAL FOREST Temporary Pond Pond: Permanent wetlands, either natural Amphibians and Reptiles of Open Grassy Upland Pine Small Creek Abundance (beaver ponds) or human impoundments, e.g. Bankhead National Forest Hardwood Checklist Summer Winter Brushy Creek Lake. Usually large areas of open Spring Pond water with pond lilies and aquatic vegetation. Fall Common Name Scientific Name Turtles Temporary Pond: Wetlands usually full during Spiny Softshell Apalone spinifera P + P P P winter and spring but dry during summer. Common Snapping Turtle Chelydra serpentina* C + + + + C C C Usually small with no outlet (isolated) and no Common Map Turtle Graptemys geographica U + + U U U large predatory fish. They are excellent breeding Alabama Map Turtle Graptemys pulchra P + P P P habitats for certain amphibians. Usually shallow Mud Turtle Kinosternon subrubrum U + + + U U U and grassy but can be very small ditches. Alligator Snapping Turtle Macrochelys temminckii ? + ? ? ? River Cooter Pseudemys concinna* C + + C U U Large Creek: Example: Sipsey Fork. 30-60 feet Flattened Musk Turtle Sternotherus depressus U + + U U U wide, with deep pools and heavy current. Large Red Milk Snake Stinkpot Sternotherus odoratus* U + + + U U U logs and snags are excellent for basking turtles. Bankhead National Forest, comprising nearly 182,000 Yellow-bellied Slider Trachemys scripta* C + + + C C C acres, represents one of the largest tracts of contiguous Often contain large boulders and flat rocks. Eastern Box Turtle Terrapene carolina* A + + + C A C forest in Alabama. The unique mixture of moist hardwood forests and drier pine uplands boasts a wide Small Creek: Small creeks draining upland Lizards variety of amphibians (26 species) and reptiles (46 Green Anole Anolis carolinensis* A + + + A A C areas; seepage areas. -

Habitat Associations of Reptile and Amphibian Communities in Longleaf Pine Habitats of South Mississippi

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 4(3):295-305. Submitted: 15 March 2008; Accepted: 9 September 2009 HABITAT ASSOCIATIONS OF REPTILE AND AMPHIBIAN COMMUNITIES IN LONGLEAF PINE HABITATS OF SOUTH MISSISSIPPI DANNA BAXLEY AND CARL QUALLS Department of Biological Sciences, The University of Southern Mississippi, 118 College Dr. #5018, Hattiesburg, Mississippi 39406, USA, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract.—Land managers and biologists do not yet thoroughly understand the habitat associations of herpetofauna native to longleaf pine forests in southern Mississippi. From 2004 to 2006, we surveyed the herpetofauna of 24 longleaf pine communities in 12 counties in south Mississippi. We quantified herpetofaunal diversity, relative abundance, and a suite of habitat variables for each site to address the following objectives: (1) determine what levels of habitat heterogeneity exist in longleaf pine forests in south Mississippi; (2) determine if reptile and amphibian community composition differs among these sites; and (3) if habitat-faunal differences exist among sites, identify what habitat variables are driving these community differences. Multivariate analysis identified three distinct longleaf pine habitat types, differing primarily in soil composition and percentage canopy cover of trees. Canonical correspondence analysis indicated that canopy cover, basal area, percentage grass in the understory, and soil composition (percentage sand, silt, and clay) were the predominant variables explaining community composition at these sites. Many species exhibited associations with some or all of these habitat variables. The significant influence of these habitat variables, especially basal area and canopy cover, upon herpetofaunal communities in south Mississippi indicates the importance of incorporating decreased stand density into management practices for longleaf pine habitat. -

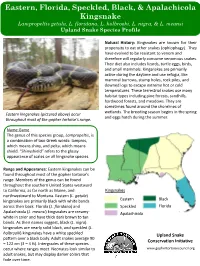

Kingsnake Lampropeltis Getula, L

Eastern, Florida, Speckled, Black, & Apalachicola Kingsnake Lampropeltis getula, L. floridana, L. holbrooki, L. nigra, & L. meansi Upland Snake Species Profile Natural History: Kingsnakes are known for their propensity to eat other snakes (ophiophagy). They have evolved to be resistant to venom and therefore will regularly consume venomous snakes. Their diet also includes lizards, turtle eggs, birds, and small mammals. Kingsnakes are primarily active during the daytime and use refugia, like mammal burrows, stump holes, rock piles, and downed logs to escape extreme hot or cold temperatures. These terrestrial snakes use many habitat types including pine forests, sandhills, hardwood forests, and meadows. They are sometimes found around the shorelines of wetlands. The breeding season begins in the spring Eastern kingsnakes (pictured above) occur and eggs hatch during the summer. throughout most of the gopher tortoise’s range. Name Game The genus of this species group, Lampropeltis, is a combination of two Greek words: lampros, which means shiny, and pelta, which means shield. “Shinyshield” refers to the glossy appearance of scales on all kingsnake species. Range and Appearance: Eastern kingsnakes can be found throughout most of the gopher tortoise’s range. Members of the genus can be found throughout the southern United States westward to California, as far north as Maine, and Kingsnakes northwestward to Montana. Eastern (L. getula) kingsnakes are primarily black with white bands Eastern Black across their back. Florida (L. floridana) and Speckled Florida Apalachicola (L. meansi) kingsnakes are creamy- Apalachicola white in color and have thick dark brown to tan bands. As their names suggest, black (L. nigra) kingsnakes are nearly solid black, and speckled (L. -

TOC-Comment-Letter-8-20-14.Pdf

2 of 50 3 of 50 4 of 50 Draft CCP Issue #1 – EXCEPTIONAL VISITOR EXPERIENCE Town Position Statement Current management of the CNWR provides an exceptional combination of visitor experiences which support the mission of the refuge and the Eastern Shore of Virginia tourism based economy with 95% visitor satisfaction*. The preferred alternative proposes significant management changes to relocate the recreational beach which have not been evaluated through the NEPA Environmental Impact Statement process or by A+ the FWS economic impact study. A master plan and economic impact statement must be prepared for Alternative B to comply with NEPA/EIS review, and to assure that the exceptional visitor experience at CNWR inside the Assateague Island National Seashore is not diminished. What is the Issue? The draft CCP/EIS for Chincoteague National Proposed Change Wildlife Refuge has not yet hit the mark with the preferred alternative. The US Fish and Wildlife The final CCP plan must be based on Service carefully describes the current successful Alternative A (current management management plan under Alternative A, and then practices to keep the exceptional selects the preferred Alternative B without recreational beach and infrastructure in place at Toms Cove), plus actions taken providing details necessary for community support. to build up and maintain the land base Lacking a site design and transition plan for the new necessary to provide resilience under recreational beach location (CCP pg. 2-68), the changing environmental conditions. preferred alternative cannot adequately demonstrate This plan would allow for a long term an exceptional visitor experience. In fact, transition to Alternative B only when significant adverse impacts are anticipated (CCP pg. -

Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge Alternative Transportation Study

Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge Alternative Transportation Study Prepared by Volpe National Transportation Systems Center 55 Broadway, Cambridge MA 02142 www.volpe.dot.gov April 2010 Table of Contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................. 1 Purpose and Need ................................................................................... 1 Background ............................................................................................. 3 Scope of ATPPL Application ................................................................................................. 3 Program Input ........................................................................................................................ 3 Approach .................................................................................................. 6 Project Overview and Methodology ....................................................................................... 6 Data Resources ....................................................................................................................... 7 2 Existing Conditions .................................................................... 8 Project Co-Applicants ............................................................................. 8 Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge (CNWR) ................................................................ 9 Assateague Island National Seashore ................................................................................