New Communication Technologies: a Challenge for Press Freedom. No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Grand Valley Ledger Wny La

€iNe w TV Magazine Hi1 n00;: In This Issue'* Hi,,, -» ^ n i • k . Complete Listings For 'the - . ai:•' Lowell Cable TV System 4 49204 0 l« Scat ri of The Grand Valley Ledger wny lA Volume 7, Issue 21 Serving Lowell Area jgf Reader* Since 1893March 30. 1983 Teachers and Board come to terms on contract After months of sometimes to them by contract paid in equal payment of from 16 to 30 percent blame already-high taxes and as- would be willing to see the bus- grams they were willing to sup- tense negotiations, the Lowell installments until the last pay of the retiree's regular teaching sessments for the March 14 mil- ing program discontinued for the port with a favorable millage MBS Hducation Association and the date of the 1982-83 school year. salary lage defeat more than anything sake of improved instructional vote. The survey listed busing, a Bill Lowell Board of Education In addition, teachers will re- In a special meeting of the else. Fifty-one percent of the re- programs This figure compares six-hour school day. extra-cur- Wednesday ratified a three-year ceive salary increases of 6 per- board held Wednesday, March spondents said that taxes were with 41 percent for non-parents ncular activities, buildings and contract agreement which gives cent for the 1983-84 school year, 23, High School Assistant Prin- the reason for the millage defeat, These results were significant grounds improvements, and in- teachers the retroactive pay in- and 6-1/2 percent for the year cipal Dick Korb explained the re- compared with 20 percent who to Korb because they seemed to structional improvements. -

BUSINESS How to Use The

t n - MANCHESTKH HERALD. Mundav. Oct. 17. 1<)H3 Manchester, Conn, j' BUSINESS Cloudy, cold tonight;. Tuesday, Oct. 18, 1983 mostly sunny Wednesday Single copy: 258 Business Holt sees quick dip in gold on horizon — See page 2 In As an investment adviser, Tom Holt's been dead their recent highs, helped In large measure by healthy CIGNA names senior VP wrong on the stock market for quite a while. Dubbed dividend puyquts. ' "super bear," he's been consistently warning of But a lower gold price (which ultimately impacts BLOOMFIELD — Stephen H. Mathenson has major breaks in the market — with the Dow tumbling Dan Dorfnian the dividends) now means lower industry revenues been appointed a senior vice president in CIGNA to the 500 to 600 level. So many who may have followed and profits. And therefore, says Holt, it's almost House unit fights Corp.'s Qroup Pension Division. his advice in recent years — which has included a certain that most mining eompanies will report Mathensoh will be responsible lor sales, new series of short sale recommendations (a bet.On lower Syndicated unfavorable.third-quarter earnings comparisons. business underwriting and major accounts, So Holt's advice: If you own any gold stocksl beat stock prices) no doubt are a lot poorer. Columnist Mathenson most recently served- as vice In one area, though. Holt has shined — his^early the crowd and sell out now. ; . president of planning for ,CIGNA and was warnings (dating back to the early '80s) that the gold Obviously, ditto on gofd itself.. , over phone rates responsible for operational and strategic plan •play was over. -

Billboard-1987-11-21.Pdf

ICD 08120 HO V=.r. (:)r;D LOE06 <0 4<-12, t' 1d V AiNE3'c:0 AlNClh 71. MW S47L9 TOO, £L6LII.000 7HS68 >< .. , . , 906 lIOIa-C : , ©ORMAN= $ SPfCl/I f011I0M Follows page 40 R VOLUME 99 NO. 47 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT November 21, 1987/$3.95 (U.S.), $5 (CAN.) CBS /Fox Seeks Copy Depth Many At Coin Meet See 45s As Strong Survivor with `Predator' two -Pack CD Jukeboxes Are Getting Big Play "Predator" two-pack is Jan. 21; indi- and one leading manufacturer Operators Assn. Expo '87, held here BY AL STEWART vidual copies will be available at re- BY MOIRA McCORMICK makes nothing else. Also on the rise Nov. 5-7 at the Hyatt Regency Chi- NEW YORK CBS /Fox Home Vid- tail beginning Feb. 1. CHICAGO While the majority of are video jukeboxes, some using la- cago. More than 7,000 people at- eo will test a novel packaging and According to a major -distributor jukebox manufacturers are confi- ser technology, that manufacturers tended the confab, which featured pricing plan in January, aimed at re- source, the two -pack is likely to be dent that the vinyl 45 will remain a say are steadily gaining in populari- 185 exhibits of amusement, music, lieving what it calls a "critical offered to dealers for a wholesale viable configuration for their indus- ty. and vending equipment. depth -of-copy problem" in the rent- price of $98.99. Single copies, which try, most are beginning to experi- Those were the conclusions Approximately 110,000 of the al market. -

Moslems Free Fhipino Nuns; American Held

g4 - MANCHESTER HERALD. Wednesday July 16. 1986 f \ } - \ MANCHESTER SPORTS TAG SALE SIGN Federal approval New Life Center Cycle in gear helps town project ( V h SAU Are things piling up? Then why not have a TAG SALE? offers new hope In softball play The best way to announce it is with a Heraid Tag Sale ... page 3 ... page 11 Classified Ad. When you piace your ad, you’ii receive ... page 15 ONE TAG SALE SIGN FREE, compliments of The Heraid. STOP IN AT OUR OFFICE, 1 HERALD SQUARE, MANCHESTER ^ HOMES HOMES KIT ‘N’ CARLYLE ®by Larry Wright FOR SALE FOR SALE BUSINESS & SERVICE DIREaORY aurh^BtrrManchester - A City of Village Charm HrralJi I CARPENTRY/ ■A, J MISCELLANEOUS MISCELLANEOUS CHILD CARE I REMOOELINfi iBi I SERVICES SERVICES Thursday, July 17, 1986 25 Cents Part time babysitter, Remodellng/Carpentry Odd lobs. Trucking. days, experience pre Work. Additions, decks Home repdirs. You name ferred, call after 5 PM. and repoirs.lnsured. Call It, we do It: Free ettl- 643-5685. David Cprmler, 649^4236. motes. Insured. 643-0304. O & O Landscaping. V < ^ Lottery tion cuttings, hedtie trim- Need A Good Tenant? miong, Prunlngs, flower Moslems free CARPENTRY/ Zimmer management will & shrub plantings. Free I I P A IN T IN G / find well qualfled, good REMODELING 0 estimates. Call 659-2436 wins out I PAPERING paying tenant for your otter 5:30pm. rentol property In East of Farrand Remodeling — Name your own price — the River area. Many Cabinets, roofing, gut Father and son. Fast, years of experience. Very Bookkeeping tuilcharge over lunch FHipino nuns; ters, room additions, dependable service. -

— Samizdat. Between Practices and Representations Lecture Series at Open Society Archives, Budapest

— Samizdat. Between Practices and Representations Lecture Series at Open Society Archives, Budapest, No February-June . Publications IAS — Samizdat. Between Practices and Representations Lecture Series at Open Society Archives, Budapest, February-June 2013. edited by valentina parisi — Co-sponsored by the Central European University Institute for Advanced Study and eurias — Colophon Parisi, Valentina (ed.) Samizdat. Between Practices and Representations Lecture Series at Open Society Archives, Budapest, February-June 2013. ias Publications No 1 © Central European University, Institute for Advanced Study 2015 Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-615-5547-00-3 First published: February 2015 Proofreading: Christopher Ryan Graphic design: Ákos Polgárdi Typefaces: Adobe Jenson & Arquitecta — Contents Acknowledgements p. 005 Preface p. 007 The common pathways of samizdat and piracy p. 019 Balázs Bodó “Music on ribs”. Samizdat as a medium p. 035 Tomáš Glanc The media dimension of samizdat. p. 047 The Präprintium exhibition project Sabine Hänsgen The dispersed author. The problem of literary authority p. 063 in samizdat textual production Valentina Parisi Movement, enterprise, network. The political economy p. 073 of the Polish underground press Piotr Wciślik Samizdat as social practice and communication circuit p. 087 Olga Zaslavskaya Authors p. 101 Index of names p. 105 — 3 — 4 — Acknowledgements This volume brings together the texts of all the lectures delivered at the Open Society Archives (OSA) in Budapest in the -

FROM SOLIDARNOŚĆ to FREEDOM International Conference Warsaw-Gdańsk August 29-31, 2005

P A R T N E R S & SP O N S O R S of our International Conference FROM SOLIDARNOŚĆ TO FREEDOM International Conference Warsaw-Gdańsk August 29-31, 2005 Conference Chairman: Bronisław Geremek Programme Director: Eugeniusz Smolar Executive Director: Henryk Sikora The Solidarity Center Foundation Lech Wałęsa Institute Warsaw-Gdańsk 2005 Conference organized by: The Solidarity Center Foundation, ul. Wały Piastowskie 24, 80-855 Gdańsk The Lech Wałęsa Institute, Al. Jerozolimskie 11/19, 00-508 Warsaw The Conference was organized under the auspices of: the Secretary General of the Council of Europe, Mr. Terry Davis and the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, OSCE Supervising Editor of both the Polish- and English-language volumes: Nina Smolar Editor of this volume: Philip Earl Steele Photos from the conference available at: www.solidarity25.pl © The Solidarity Center Foundation, 2005 ISBN 978-83-60089-18-7 EAN 9788360089187 Our conference and this publication were made possible thanks to the financial support of the European Commission. The addresses and comments delivered at the conference – and, thus, the texts contained in this publication – reflect the views of their authors. The European Commission cannot be held responsible for their substance. The Solidarity Center Foundation and the Lech Wałęsa Institute would like to thank the Government of the Republic of Poland and the Council for the Protection of the Memory of Combat and Martyrdom for their financial support. The approaching 25th anniversary of the founding of NSZZ "Solidarność" prompts us to take a look back at history and ask questions about our future. The path blazed by "Solidarność" has opened new civilizational opportunities. -

Britain Severs Ties with Libya

5,000 attend Easter parade under cloudy skies, B1 GREATER RED BANK EATONTOWN Serious condition Sixers hang tough LONG BRANCH Middletown policeman Stave off elimination battles rare disease. Today's Forecast by beating Nets, 108-100. More rain today Page A7 Page B2 Complete weather on A2 The Daily Register VOL. 106 NO. 24!49 YOUR HOMETOWN NEWSPAPER . SINCE 1878 ^"""^ MONDAY, APRIL 23, 19198£ 4 . 25 CENTS Britain severs ties with Libya LONDON (AP) - Britain sev- ered diplomatic relations with Libya and ordered the Libyan Embassy vacated within a week — a move officials concede is likely to mean freedom for the gunman who killed a policewomen and wounded 11 Libyan dissidents. Libya expressed "astonishment and displeasure" at the British order, announced yesterday, and declared it "holds the British government responsible for this decision and its consequences." The move was designed to end a diplomatic standoff that began last Tuesday, when a submachine gun was fired from an embassy window at Libyan exiles demonstrating against Col. Moammar Khadafy's regime, killing Constable Yvonne Fletcher and injuring 11 protesters. EASTER WORSHIP •» Worshipers leaving Middletown. after Easter services. The five-story building has been Christ Episcopal Church, Kings Highway, ringed by police marksmen since then. Libya gave no indication when the 20 to 30 diplomats and students in the embassy would leave. Britain Families enjoy Easter said the building in St. James's Square will lose its diplomatic status — and immunity from assault — at midnight Sunday. Home Secretary Leon Brittan despite chilly weather said the emerging Libyans would be searched for arms but will be given The weather wasn't perfect on Long Branch, Easter business safe passage home. -

Contras Kidnap Americans KIDNAPPED

Baseball players go back to work today, 1B Cloudy Chance of showers Highs in the low 80s The Register Complete forecast/Pip 2A Vol. 107 No. 344 YOUR HOMETOWN NEWSPAPER .SINCE 1878 THURSDAY, AUGUST 8, 1985 ?5 CENTS AMERICANS INSIDE Contras kidnap Americans KIDNAPPED United States for the incident and said: "We has sent three embassy officers by auto to the SPORTS MANAGUA, Nicaragua (API - US-backed hold the government of the United States area. It's a three-hour drive. We expect them to rebels firing automatic weapons kidnapped 29 responsible for the physical integrity of the be be there sometime tonight " American peace activists and 18 journalists kidnapped." And in San Jose, Costa Rica, U.S. Embassy yesterday from a boat on the river dividing In Washington, a spokesman for the peace spokesman Mark Krischik said: "The embassy Nicaragua and Costa Rica, spokesmen for the group, Richard K. Taylor, made a similar is sifting through information and if any U.S. group and the government said statement to reporters. "We will hold President citizen has been kidnapped we will work to Herb Gunn, of Fayetteville, Ark., deputy Reagan and those members of Congress who achieve their release, just as we would in the coordinator of the Witness for Peace group, told voted for Contra (rebel) aid responsible for any United States or in Beirut or anywhere " reporters in Managua he contacted the rebels by injuries inflicted on the people in our group," he The communique, broadcast by state radio, radio and was told the Americans were said. said 29 Americans of the U.S. -

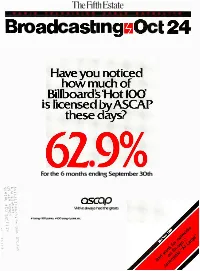

Broadcastingii Oct 24

The Fifth Estate Broadcastingii Oct 24 Have you noticed how much of Billboard's `Hot 100' is licensed byASCAP these days? For the 6 months ending September 30th We've always had the greats it song '100 points. #100 song.] polrn.etc. a.) n a C COLUMBIA PICTURES INDUSTRIES, INC 1983 49,u Cf Cßl1GPfI Lrn/6h3c*k.Yewei/J4 A RONA II and Spelling /Goldberg Production in association with ,,S/94)1 Your winn ng combination for AM Stereo o 011111° (),, NEGATIVE LETT POSITIVE RIG I SIT CARRIER O CONTINENTAL ELECTRONICS TYPE Phil-EMI AM STEREO MOO. MONITOR _i lo ~661 TO R, CCIhEA LET TO 100 o OAT LITT 5.101*? IR OUTPUT g0:71 L ANOTO OUTPUT RI U OUTPUT roa óÌMÓó c,IPPL.nn o AS ,I Is AM Stereo ready to move up? Hearing is believing. on -air reliability with complete Market -place decisions With the PMX System, AM Stereo transparency. notwithstanding, the recent music sounds like FM Stereo Ultimately, the day -to-day introduction of receivers able to music. So it makes for higher operation of your AM Stereo decode signals from any of the four listener appeal and better System will depend upon systems in use today makes it numbers: For audience and the equipment and service. easier for broadcasters to move bottom line. We stand on our track record of ahead with AM Stereo plans. The Winning Combination providing the best of both. Which system is #1? Our Type 302A Exciter, developed If you're considering AM Stereo, or The PMX (Magnavox) System was for the PMX System, and our new if you just want more facts, give us first selected by the FCC to be the Type PMX -SM 1 AM Stereo a call. -

May 2018 1 Periodical Postageperiodical Paid at Boston, New York

1918 • ceNteNNiAl of PolANd’SPOLISH rebirth AMERICAN • JOURNAL 2018 • MAY 2018 www.polamjournal.com 1 PERIODICAL POSTAGE PAID AT BOSTON, NEW YORK NEW BOSTON, AT PAID PERIODICAL POSTAGE POLISH AMERICAN OFFICES AND ADDITIONAL ENTRY JOURNALDEDICATED TO THE PROMOTION AND CONTINUANCE OF POLISH AMERICAN CULTURE before rob, there wAS iggy ESTABLISHED 1911 MAY 2018 • VOL. 107, NO. 5 • $2.25 www.polamjournal.com PAGE 14 POLONIA’S MATERNAL SPIRIT • HONORS FOR BENETAR • MAHER CALLS IMPRUDENT BUSINESS PLAN “POLISH” CHRZANOWSKA BECOMES FIRST R.N. TO BE CONSIDERED FOR SAINTHOOD • OWN A PIECE OF POLISH ART HISTORY KRASZEWSKI GIVES MICKIEWICZ’S DZIADY A NEW AUDIENCE • POLONIA PLACES: ST. CASIMIR’S CHURCH, KENOSHA Newsmark Orchard Lake Recognition Well-Deserved Schools Names Polish Ambassador Piotr PolANd SigNS deAl to buy AMericAN Air-de- Wilczek (left) presents dr. feNSe SySteM. Poland has signed an historic deal to Polish Mission thaddeus V. gromada with a buy American Patriot air-defense systems for $4.75 billion. “Nominations Diploma,” which The fi rst Patriot systems are expected to reach Poland by Director ORCHARD LAKE, Mich. certifi es the noted historian 2022, followed by additional deliveries in 2024. as an elected foreign member The contract was signed by Polish Defense Minis- — The Orchard Lake Schools announced its selection of Dr. of the Polska Akademia ter Mariusz Błaszczak at a ceremony in Warsaw attend- Umiejętności (Polish Academy ed by President Andrzej Duda, Prime Minister Mateusz Arkadiusz Gorecki as its Di- rector of The Polish Mission. of Arts & Sciences) based in Morawiecki, and the U.S. ambassador to Poland, Paul W. Kraków. -

Resistance: the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

RESISTANCE l(� RESISTANCE l(� THE WARSAW GHETTO UPRISING Israel Gutman Published in association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum A Marc Jaffe Book HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY BOSTON NEW YORK 1994 Copyright © 1994 by Israel Gutman All rights reserved For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gutman, Israel. Resistance : the Warsaw Ghetto uprising I Israel Gutman. p. em. "A Marc Jaffe book." "A publication of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum." Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-395-60199-1 1. Jews- Poland- Warsaw- Persecutions. 2. Holocaust, Jewish (1939-1945)- Poland- Warsaw. 3· Warsaw (Poland)- History- Uprising of 1943. 4· Warsaw (Poland)- Ethnic relations. I. Title. DSI35-P62W2728 1994 943.8'4-dc20 93-46767 CIP Printed in the United States of America AGM 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 I Maps copyright© 1993 United States Holocaust Memorial Council "Campo dei Fiori" from The Collected Poems by Czeslaw Milosz. Copyright © 1988 by Czeslaw Milosz Royalties, Inc. Reprinted by permission of the publisher, The Ecco Press. In memory of Irit CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ix INTRODUCTION xi I . The First Weeks of War I 2. The Jews of Warsaw Between the Wars I4 3 · A New and Different Existence 49 4. The Ghetto Is Sealed 7I 5 ·The Turning Point 99 6 . Political Parties and Youth Movements I 20 7 · Deportation to Death I3 3 8 . The Establishment of the Jewish Fighting Organization 146 9. -

Copyrighted Material

bindex.qxd 11/10/04 10:29 AM Page 332 INDEX Page numbers in italic type refer to photos. A. Philip Randolph Institute, 49, 147, African Americans, 147–148, 235 266 African National Congress, 235 Abel, I.W., 50, 55, 73, 81 Agee, Philip, 186 abortion, 268–272 Airline Pilots, 113, 125 Abzug, Bella, 60, 76, 137 air traffic controllers, 122–128, 255, affirmative action, 268–269 277–278 AFL-CIO (American Federation of Alexander, Lawrence Sterling, 14 Labor-Congress of Industrial Allen, Richard V., 126, 192 Organizations). See also American Allende, Salvador, 234 Institute for Free Labor Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Development (AIFLD); Committee Workers, 103, 260 on Political Education (COPE); American Center for International Labor individual names of labor leaders, politi- Solidarity, 213 cians, unions American Committee on U.S.-Soviet Ad Hoc Committee on Reproductive Relations, 245 Issues, 270–273 American Federation of Government on communism, 67–71 Employees (AFGE), 103, 212 on contra aid, 208 American Federation of Labor (AFL), on defense, 91–92, 132–134 30–37 Department of Social Security, 39 AFL-CIO merger, 38–39 in Eastern Europe, 232 history of, 30–31 Evolution of Work Committee, American Federation of State, County, 258–261 and Municipal Employees executive council, 56, 102–103, (AFSCME), 73, 75, 299, 302, 307 133–134, 266–268, 295 American Federation of Teachers, 84, financial assistance to Polish Solidarity, 95–96, 101 165–167, 169–170, 186, 188–189 American Institute for Free Labor membership level,COPYRIGHTED 83, 260, 297, 306