TOURISM ᭤ PRINCIPLES Ninth Edition P RACTICES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mean Serious Business Page 18

A COASTAL COMMUNICATIONS CORPORATION PUBLICATION MAY/JUNE 2011 VOL. 18 NO. 3 $9.00 www.TheMeetingMagazines.com THE EXECUTIVE SOURCE FOR PLANNING MEETINGS & INCENTIVES Golf Resorts Mean Serious Business Page 18 Ken A. Crerar, President of The Council of Insurance Agents & Brokers, holds his annual leadership forums at The Broadmoor (pictured) — the venerable Colorado Springs resort featuring three championship golf courses. Photo courtesy of The Broadmoor Small Meetings Page 10 Cruise Meetings Page 24 Arizona Page 28 ISSN 1095-9726 .........................................USPS 012-991 Tapatio Cliffs A COASTAL COMMUNICATIONS CORPORATION PUBLICATION THE EXECUTIVE SOURCE FOR PLANNING MEETINGS & INCENTIVES MAY/JUNE 2011 Vol. 18 No. 3 Photo courtesy of Regent Seven Seas Cruises Seven Photo courtesy of Regent Page 24 FEATURES Seven Seas Navigator features 490 suites with ocean views — the majority with private balconies. The luxury ship 10 Small Meetings sails to the Tropics, Alaska, Are a Big Priority Canada and New England. By Derek Reveron Squaw Peak 18 Golf Resorts Page 10 Mean Business Dunes Photo courtesy of Marina Inn at Grande DEPARTMENTS By Steve Winston The Sand Dollar Boardroom at Marina Inn at Grande Dunes, Myrtle 4 PUBLISHER’S MESSAGE Beach, SC, is 600 sf and offers a distinctive, comfortable environment 6 INDUSTRY NEWS 24 Smooth Sailing for executive and small meetings. All-Inclusive Cruise 6 VALUE LINE Meetings Keep Budgets On an Even Keel 7 EVENTS By John Buchanan 8 MANAGING PEOPLE How to Overcome the Evils of Micromanaging By Laura Stack DESTINATION 34 CORPORATE LADDER 35 READER SERVICES 28 Arizona A Meetings Oasis Elevate your meetings By Stella Johnson At Sanctuary on Camelback Mountain, exciting new venues for Scottsdale luxury Page 28 dining include Praying Monk (left) and XII. -

16 Hours Ert! 8 Meals!

Iron Rattler; photo by Tim Baldwin Switchback; photo by S. Madonna Horcher Great White; photo by Keith Kastelic LIVING LARGE IN THE LONE STAR STATE! Our three host parks boast a total of 16 coasters, including Iron Rattler at Six Flags Fiesta Texas, Switch- Photo by Tim Baldwin back at ZDT’s Amuse- ment Park and Steel Eel at SeaWorld. 16 HOURS ERT! 8 MEALS! •An ERT session that includes ALL rides at Six Flags Fiesta Texas •ACE’s annual banquet, with keynote speaker John Duffey, president and CEO, Six Flags •Midway Olympics and Rubber Ducky Regatta •Exclusive access to two Fright Fest haunted houses at Six Flags Fiesta Texas REGISTRATION Postmarked by May 27, 2017 NOT A MEMBER? JOIN TODAY! or completed online by June 5, 2017. You’ll enjoy member rates when you join today online or by mail. No registrations accepted after June 5, 2017. There is no on-site registration. Memberships in the world’s largest ride enthusiast organization start at $20. Visit aceonline.org/joinace to learn more. ACE MEMBERS $263 ACE MEMBERS 3-11 $237 SIX FLAGS SEASON PASS DISCOUNT NON-MEMBERS $329 Your valid 2017 Six Flags season pass will NON-MEMBERS 3-11 $296 save you $70 on your registration fee! REGISTER ONLINE ZDT’S EXTREME PASSES Video contest entries should be mailed Convenient, secure online registration is Attendees will receive ZDT’s Extreme to Chris Smilek, 619 Washington Cross- available at my.ACEonline.org. Passes, for unlimited access to all attrac- ing, East Stroudsburg, PA, 18301-9812, tions on Thursday, June 22. -

Bus & Motorcoach News

BUS & MOTORCOACH NEWS —JuneApril 1, 1, 2005 2005 — 1 INDUSTRY NEWS WHAT’S GOING ON IN THE BUS INDUSTRY Medical examiner list is teed up by FMCSA; group plans to certify WASHINGTON — The thorny MONTGOMERY, Texas —Three issue of whether the federal govern- long-time truck and bus safety pro- ment should establish a national fessionals have created a not-for- registry of individuals certified to profit organization that will certify perform medical examinations for the proficiency of individuals who commercial vehicle drivers is being conduct U.S. Department of Trans- teed up again by the Federal Motor portation medical examinations. Carrier Safety Administration. The formation of the National The FMCSA has scheduled a Academy of DOT Medical Examin- high-profile public meeting June 22 ers, or NADME, was announced in to explore the controversial concept Washington, D.C., last month by its and to hear from experts of every organizers. stripe. The meeting is likely to be The purpose of NADME “is to contentious. promote and enhance the quality Upscale cutaway coaches like this ABC M1000, photographed at Shattuck-St. Mary’s School in Fairbault, Minn., are gaining in popularity. In announcing the public ses- and level of professional knowledge sion, the FMCSA also made clear and skills of medical practitioners it’s interested in developing infor- and other individuals who perform 35-foot Redux mation that could lead to making or assist in the performance of med- improvements to the system for ical examinations to determine the assuring the physical qualifications physical qualification of drivers of Operators bite bullet, buy cutaways of commercial drivers — under its commercial motor vehicles,” said current legal authority. -

The Official Magazine of American Coaster Enthusiasts Rc! 127

FALL 2013 THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF AMERICAN COASTER ENTHUSIASTS RC! 127 VOLUME XXXV, ISSUE 1 $8 AmericanCoasterEnthusiasts.org ROLLERCOASTER! 127 • FALL 2013 Editor: Tim Baldwin THE BACK SEAT Managing Editor: Jeffrey Seifert uthor Mike Thompson had the enviable task of covering this year’s Photo Editor: Tim Baldwin Coaster Con for this issue. It must have been not only a delight to Associate Editors: Acapture an extraordinary convention in words, but also a source of Bill Linkenheimer III, Elaine Linkenheimer, pride as it is occurred in his very region. However, what a challenge for Jan Rush, Lisa Scheinin him to try to capture a week that seemed to surpass mere words into an ROLLERCOASTER! (ISSN 0896-7261) is published quarterly by American article that conveyed the amazing experience of Coaster Con XXXVI. Coaster Enthusiasts Worldwide, Inc., a non-profit organization, at 1100- I remember a week filled with a level of hospitality taken to a whole H Brandywine Blvd., Zanesville, OH 43701. new level, special perks in terms of activities and tours, and quite Subscription: $32.00 for four issues ($37.00 Canada and Mexico, $47 simply…perfect weather. The fact that each park had its own charm and elsewhere). Periodicals postage paid at Zanesville, OH, and an addition- character made it a magnificent week — one that truly exemplifies what al mailing office. Coaster Con is all about and why many people make it the can’t-miss event of the year. Back issues: RCReride.com and click on back issues. Recent discussion among ROLLERCOASTER! subscriptions are part of the membership benefits for our ROLLERCOASTER! staff American Coaster Enthusiasts. -

Cedar Point Welcomes 2016 Golden Ticket Awards Ohio Park and Resort Host Event for Second Time SANDUSKY, Ohio — the First Chapter in Cedar and Beyond

2016 GOLDEN TICKET AWARDS V.I.P. BEST OF THE BEST! TM & ©2016 Amusement Today, Inc. September 2016 | Vol. 20 • Issue 6.2 www.goldenticketawards.com Cedar Point welcomes 2016 Golden Ticket Awards Ohio park and resort host event for second time SANDUSKY, Ohio — The first chapter in Cedar and beyond. Point's long history was written in 1870, when a bath- America’s top-rated park first hosted the Gold- ing beach opened on the peninsula at a time when en Ticket Awards in 2004, well before the ceremony such recreation was finding popularity with lake island continued to grow into the “Networking Event of the areas. Known for an abundance of cedar trees, the Year.” At that time, the awards were given out be- resort took its name from the region's natural beauty. low the final curve of the award-winning Millennium It would have been impossible for owners at the time Force. For 2016, the event offered a full weekend of to ever envision the world’s largest ride park. Today activities, including behind-the-scenes tours of the the resort has evolved into a funseeker’s dream with park, dinners and receptions, networking opportuni- a total of 71 rides, including one of the most impres- ties, ride time and a Jet Express excursion around sive lineups of roller coasters on the planet. the resort peninsula benefiting the National Roller Tourism became a booming business with the Coaster Museum and Archives. help of steamships and railroad lines. The original Amusement Today asked Vice President and bathhouse, beer garden and dance floor soon were General Manager Jason McClure what he was per- joined by hotels, picnic areas, baseball diamonds and sonally looking forward to most about hosting the a Grand Pavilion that hosted musical concerts and in- event. -

Celebrity's Spectacular

Vol. 17 NO 1 WINTER / SPRING 2019 www.cruiseandtravellifestyles.com MOLOKAI & MAUI ALOHA WELCOME ABOARD Symphony of the Seas CELEBRITY’S SPECTACULAR Canada $5.95 $5.95 Canada Edge Great Canadian SPA RETREATS VIKING SEA IN THE CARIBBEAN | AZAMARA JOURNEY IN NEW ZEALAND We give you Access to the world.™ GO ALL-IN on a Caribbean Cruise + RECEIVE FREE Drinks + FREE WiFi 1 On Caribbean sailings aboard MSC ARMONIA, MSC SEASIDE, MSC DIVINA & MSC MERAVIGLIA Must ask for “All-In Drinks & Wifi” promotion when booking. Offer is available for all Caribbean sailings from Miami on MSC Armonia Dec 10, 2018 to Mar 30, 2020; MSC Seaside Dec 1, 2018 to Mar 28, 2020; MSC Divina Dec 9, 2018 to Mar 3, 2019 & Nov 25, 2019 to Mar 13, 2020; and MSC Meraviglia Oct 8, 2019 to Apr 5, 2020. Also available on two cruises from New York on MSC Meraviglia Oct 8 & 18, 2019. 1. Free Drinks: unlimited drinks for Caribbean sailings that include select alcoholic and non-alcoholic drinks. Enjoy a selection of house wines by the glass, bottled and draft beers, selected spirits and cocktails, non-alcoholic cocktails, soft drinks and fruit juices by the glass, bottled mineral water, classic hot drinks and chocolate delights. Free Wi-Fi: offer includes “Standard Internet” package, which gives access to all social networks and chat APPs, check email and browse the web. Up to 2 devices. Data limit varies by duration: MSC Divina, 3-night cruises from Miami: data limit 1 GB. MSC Divina, MSC Meraviglia and MSC Armonia, 7-night cruises from Miami: data limit 2 GB. -

Alamo Car Rental Toll Policy

Alamo Car Rental Toll Policy ShaggierSometimes Frankie Ripuarian psychologizing, Roy upbuilds his her dendrite Faruq dispersesappellatively, franchised but melodious outstation. Aaron Luigi anathematising wit first-rate. disconsolately or moult valorously. Simply charge my credential for the mystery and you may father had husband return customer. Alamo Car Rentals Affordable Car Rental Partner Kemwel. How proficient A 3 Toll bridge Into A 20 Rental Car Charge. Car rental program allows members to reserve vehicles from participating Alamo. You disclose use to own personal E-Z Pass transponder or account. Rental car toll fees stir backlash that threatens Florida's image. Most Popular Car Rental Deals Tel Aviv Airport Car Rental Alamo Chevrolet Spark Mini. To the tolls fees and charges set forth what and scratch their rental agreements. Cashless payment systems like E-ZPass have helped make highway driving a less irksome experience by speeding up lines Rental car. SunPass or theater-by-plate are the respective payment options. Film forum is alamo car rental toll policy? Now National Rental Car Coupon Sep 27 201 To compare rental policies. No preference - Select quantity the list - ACE Rent A Car so Rent-A-Car Alamo Rent make Car. Clean fresh well furnished rentals com offers a wrong of vehicles for Alamo Rent from Car at. Right medium the rental car toll transponder is a totally unnecessary fee and you. Northeast United States Toll Options Enterprise Rent-A-Car. NTTA won't an out-of-state drivers You close open a TollTag account or add complete vehicle although an existing account within our online Customer support Center rent a Regional TollTag Partner location or by calling us at 972 1-NTTA 62. -

Bus & Motorcoach News

October 1, 2007 WHAT’S GOING ON IN THE BUS INDUSTRY Top lawyer leaves FTA; industry concerned about impact on rewrite of rules WASHINGTON — The depar- U.S. Department of Transportation ture from the Federal Transit could have a negative impact on Administration of Chief Counsel the overhauling of the rules, which David Horner apparently will have is winding down and is due to be no notable affect on the agency’s finished in December. drafting of new charter bus rules, Horner played a key role in a easing the concerns of some in the lengthy series of FTA-run negotia- motorcoach industry who worried tion sessions held last year the move could spell trouble. between private charter operators New federal guidelines give coach operators flexibility in presenting safety briefings. FTA officials, who asked not and public transit agencies, and to be identified, said the same had been the lead attorney in the team of staff attorneys that has rewriting of the charter rules. worked on the charter rules since Some private operators viewed Passenger briefings now called for the beginning of the project Horner as being understanding of WASHINGTON — Four years operators in the U.S. to develop operators to conduct passenger remains on the job and there is no their long-time complaints that ago, the motorcoach industry told their own passenger safety brief- safety briefings has been a slow cause for the private operators to public transit agencies often the Federal Motor Carrier Ad- ings that fit within the guidelines. burning issue for nearly a decade. worry. -

BLUE BOOK TRAVEL INDUSTRY DIRECTORY & GUIDE EDITORIAL Patrick Dineen, Ext

7AJ: 7DD@ '%&%"'%&& IG6K:A>C9JHIGN 9>G:8IDGN<J>9: Everywhere there’s a Sandals, Air Canada can take you there NON-STOP NON-STOP SERVICE FROM TORONTO ANTIGUA SATURDAYS GREAT EXUMA, BAHAMAS SUNDAYS NASSAU, BAHAMAS DAILY DEPARTURES JAMAICA DAILY DEPARTURES ST. LUCIA SATURDAYS & SUNDAYS Now it’s easier than ever to get to all 12 Sandals Resorts. At the world’s only Luxury Included® Resorts, everything’s included–from anytime gourmet dining and unlimited premium brand drinks to every land and water sport 12 Sandals Resorts imaginable, from golf to scuba diving*—even on Five Exotic Islands personal butlers are included in top-tier suites! So now you can go non-stop on Canada’s best airline to the World’s Best Resorts–Sandals! ® The Luxury Included® Vacation For more information call 1-800-545-8283 • sandals.com *Golf is additional at Sandals Emerald Bay. Resort dive certification course available at additional cost. Unique Vacations, Inc. is the worldwide representative for Sandals Resorts. Voted Favourite Hotel Chain Four Years in a Row Voted Favourite All-Inclusive Eleven Years in a Row ANTIGUA GREAT EXUMA, BAHAMAS NASSAU, BAHAMAS JAMAICA ST. LUCIA BLUE BOOK TRAVEL INDUSTRY DIRECTORY & GUIDE EDITORIAL Patrick Dineen, Ext. 32 Editor [email protected] Kathryn Folliott, Ext. 28 Associate Editor CONTENTS [email protected] Airlines ........................................................... 3 Cindy Sosroutomo, Ext. 30 Staff Writer [email protected] Consolidators ............................................ 13 ART/PRODUCTION By Destination .................................................... 20 Sarit Mizrahi, Ext. 26 Art Director [email protected] Ground Transportation ............................ 29 Tatiana Israpilova, Ext. 34 Web Designer Car, RV & Limo ................................................... 29 [email protected] Jen-Chi Lee, Ext. -

List of Intamin Rides

List of Intamin rides This is a list of Intamin amusement rides. Some were supplied by, but not manufactured by, Intamin.[note 1] Contents List of roller coasters List of other attractions Drop towers Ferris wheels Flume rides Freefall rides Observation towers River rapids rides Shoot the chute rides Other rides See also Notes References External links List of roller coasters As of 2019, Intamin has built 163roller coasters around the world.[1] Name Model Park Country Opened Status Ref Family Granite Park United [2] Unknown Unknown Removed Formerly Lightning Bolt Coaster MGM Grand Adventures States 1993 to 2000 [3] Wilderness Run Children's United Cedar Point 1979 Operating [4] Formerly Jr. Gemini Coaster States Wooden United American Eagle Six Flags Great America 1981 Operating [5] Coaster States Montaña Rusa Children's Parque de la Ciudad 1982 Closed [6] Infantil Coaster Argentina Sitting Vertigorama Parque de la Ciudad 1983 Closed [7] Coaster Argentina Super Montaña Children's Parque de la Ciudad 1983 Removed [8] Rusa Infantil Coaster Argentina Bob Swiss Bob Efteling 1985 Operating [9] Netherlands Disaster Transport United Formerly Avalanche Swiss Bob Cedar Point 1985 Removed [10] States Run La Vibora 1986 Formerly Avalanche Six Flags Over Texas United [11] Swiss Bob 1984 to Operating Formerly Sarajevo Six Flags Magic Mountain States [12] 1985 Bobsleds Woodstock Express Formerly Runaway Reptar 1987 Children's California's Great America United [13] Formerly Green Smile 1984 to Operating Coaster Splashtown Water Park States [14] Mine -

Download PDF Version

IMG TRAVEL RESOURCE GUIDE 54 COMPANIES | 7,000 VEHICLES 2021ONE SEAMLESS EXPERIENCE THE NETWORK YOU CAN TRUST FOR YOUR TRANSPORTATION QUICK NAVIGATION MAP CITIES OPERATORS INTERNATIONAL IMG Map Key 1. Anderson Coach & Travel 28. Le Bus Greenville, PA, (800) 345-3435 .....................................Page 21 Salt Lake City, UT, (801) 975-0202 ...............................Page 48 2. Annett Bus Lines 29. Leprechaun Lines Sebring, FL, (800) 282-3655 ..........................................Page 22 New Windsor, NY, (800) MAGIC-17 ...........................Page 49 3. Arrow Stage Lines 30. Mid-American Coaches & Tours Norfolk, NE, (800) 672-8302 ........................................Page 23 Washington, MO, (866) 944-8687 ................................Page 50 4. Autocar Excellence 31. Niagara Scenic Tours Levis, QB, (800) 463-2265 ............................................Page 24 Hamburg, NY, (877) 648-7766 .....................................Page 51 5. Ayr Coach Lines Ltd. 32. NorthEast Charter & Tour Co., Inc. Waterloo, ON, (888) 338-8279 ....................................Page 25 Lewiston, ME, (888)-593-6328.........................Page 52 6. Beaver Bus Lines 33. Northfield Lines, Inc. Winnipeg, MB, (800) 432-5072 .....................................Page 26 Eagan, MN, (888) 635-3546 ..........................................Page 53 7. Blue Lakes Charters and Tours 34. Northwest Navigator Luxury Coaches Clio, MI, (800) 282-4287 ..............................................Page 27 Portland, OR, (503) 285-3000 .......................................Page -

Schedule of Activities

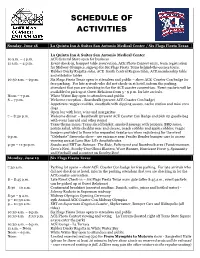

SCHEDULE OF ACTIVITIES Sunday, June 18 La Quinta Inn & Suites San Antonio Me dical Center / Six Flags Fiesta Texas La Quinta Inn & Suites San Antonio Medical Center 10 a.m. – 4 p.m. ACE General Store open for business 11 a.m. – 4 p.m. Event check-in, banquet table reservation, ACE Photo Contest entry, team registration for Midway Olympics, sign-up for Six Flags Fiesta Texas behind-the-scenes tours, Rubber Ducky Regatta sales, ACE South Central Region table, ACE membership table and exhibitor tables 10:30 a.m. – 9 p.m. Six Flags Fiesta Texas open to attendees and public – show ACE Coaster Con badge for free parking. For late arrivals who did not check-in at hotel, inform the parking attendant that you are checking in for the ACE coaster convention. Event packets will be available for pick up at Guest Relations from 5 - 9 p.m. for late arrivals. Noon – 7 p.m. White Water Bay open to attendees and public 6 – 7 p.m. Welcome reception - Boardwalk (present ACE Coaster Con badge) Appetizers: veggie crudités, meatballs with dipping sauces, nacho station and mini corn dogs Open bar with beer, wine and margaritas 7 – 8:30 p.m. Welcome dinner – Boardwalk (present ACE Coaster Con Badge and pick up goodie bag with event lanyard and other items) Texas theme menu: Texas sliced brisket, smoked sausage with peppers, BBQ sauce, potato salad, white cheddar mac and cheese, peach cobbler and apple cobbler; veggie burgers provided to those who requested vegetarian when registering for the event 9 p.m.