Trees for the Land

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Education Resource for Schools: Part Three: Plants Pages 142-165

Mahoe Melicytus ramifl orus Whiteywood This is one of the most common trees to be found on Tiritiri Matangi Island, and is especially obvious along the Wattle Valley Track. What does it look like? Mahoe is a small tree with a smooth whitish trunk covered in patches of fi ne white lichen. Mahoe grows quite quickly, and branches start quite close to the ground. Young leaves are bright green and their edges are serrated. Mahoe trees mainly fl ower in November / December but sometimes on Tiritiri Matangi they also fl ower in April / May and the masses of little creamy fl owers give out a lovely scent. When the fl owers fi nish they develop into little green berries which then ripen into a bright purple colour by January to March. What can be found living on it? Tree wetas can often been found in mahoe trees because it is a favourite food of theirs. Birds love the fruit, and on Tiritiri Matangi visitors can often see kokako, bellbirds, saddlebacks and tui when the trees are fl owering or fruiting, and they also join robins in looking for insects in nooks and crannies in the bark and under the dead leaves beneath the trees. 142 Tiritiri Matangi: An education resource for schools Has it a use for humans? The branches are too brittle and the rest of the wood is too soft to be much use, but old time maori sometimes used a sharply pointed piece of kaikomako on a fl at piece of mahoe to create a channel full of fi ne dust which when rubbed vigorously, would start to smoke and then could be fanned into a fl ame. -

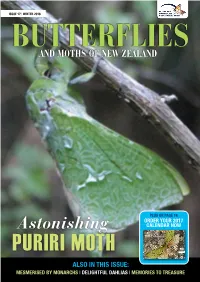

Issue 17 Hyperlinks

1ISSUE 17 | WINTER 2016 PlUS oN PagE 16 oRdER yoUR 2017 Astonishing calENdaR NoW 2017 Calendar puriri moth SPONSORED BY alSo IN ThIS ISSUE: MESMERISEd by MoNaRchS | dElIghTfUl dahlIaS | MEMoRIES To TREaSURE 2 I am sure you will be fascinated by our puriri moth featuring in this issue. Not From the many people realise that they take about five years from egg to adult… and then Editor live for about 48 hours! If you haven’t got dahlias growing idwinter usually means in your garden, you’ll change a dearth of butterflies your mind when you read CoNtENtS M but this year has certainly not our gardening feature. As well, Brian Cover photo: Nicholas A Martin been typical. At Te Puna Quarry Park Patrick tells of another fascinating moth. there are hundreds (yes, hundreds) of We are very excited about events that 2 Editorial monarch caterpillars and pupae. In my are coming up: not only our plans for our garden my nettles are covered with beautiful forest ringlet but our presence hundreds (yes, hundreds) of admiral at two major shows in Auckland in 3 Certification larvae in their little tent cocoons, November. Thanks to the Body Shop overwintering. My midwinter nectar is On another note, we have plans covered in monarchs, still mating and for rolling out the movie Flight of the 4-5 Ghosts Moths & egg-laying. It could make for a very busy, Butterflies in 3D to a cinema near you. early spring! Because it will be another three months Puriri Moths One of the best parts of my work for before our next magazine we urge you the MBNZT is seeing people’s delight to sign up for our e-news (free) to keep 6 The Trust at Work at a butterfly release. -

Behaviour and Activity Budgeting of Reproductive Kiwi in a Fenced Population

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Behaviour and Activity Budgeting of Reproductive Kiwi in a Fenced Population A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Science In Zoology At Massey University, Manawatu Jillana Robertson 2018 Abstract North Island brown kiwi (Apteryx mantelli) are flightless, nocturnal, usually solitary, and secretive birds, so knowledge of their behaviour is limited. In this study, I endeavoured to obtain a more detailed understanding of adult kiwi behaviour within two pest fenced areas focusing around the breeding season at the 3363 ha Maungatautari Scenic Reserve in Waikato, New Zealand. Within Maungatautari’s pest free enclosures, I attempted to determine male and female activity patterns over 24-hours from activity transmitter data; document diurnal and nocturnal behaviours of kiwi using video cameras; determine size and distribution of home ranges; and establish patterns of selection of daytime shelter types. Male kiwi were fitted with Wild Tech “chick timer” transmitters which recorded activity for the previous seven days. Incubating males spent significantly less time active than non incubating males with some activity occurring during the daytime. Non-incubating male activity duration decreased but activity as a proportion of night length increased with decreasing night length. Less active incubating males, suggesting more time caring for eggs, had more successful clutches. Female activity was recorded using an Osprey receiver/datalogger and 30x60x90 pulse activity transmitters. -

Patterns of Flammability Across the Vascular Plant Phylogeny, with Special Emphasis on the Genus Dracophyllum

Lincoln University Digital Thesis Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: you will use the copy only for the purposes of research or private study you will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of the thesis and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate you will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from the thesis. Patterns of flammability across the vascular plant phylogeny, with special emphasis on the genus Dracophyllum A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of philosophy at Lincoln University by Xinglei Cui Lincoln University 2020 Abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of philosophy. Abstract Patterns of flammability across the vascular plant phylogeny, with special emphasis on the genus Dracophyllum by Xinglei Cui Fire has been part of the environment for the entire history of terrestrial plants and is a common disturbance agent in many ecosystems across the world. Fire has a significant role in influencing the structure, pattern and function of many ecosystems. Plant flammability, which is the ability of a plant to burn and sustain a flame, is an important driver of fire in terrestrial ecosystems and thus has a fundamental role in ecosystem dynamics and species evolution. However, the factors that have influenced the evolution of flammability remain unclear. -

THE WETA News Bulletin of the ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY of NEW ZEALAND

THE WETA News Bulletin of THE ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF NEW ZEALAND Volume 47 July 2014 ISSN 0111-7696 THE WETA News Bulletin of the Entomological Society of New Zealand (Inc.) [Now ONLINE at http://ento.org.nz/nzentomologist/index.php] Aims and Scope The Weta is the news bulletin of the Entomological Society of New Zealand. The Weta, like the society’s journal, the New Zealand Entomologist, promotes the study of the biology, ecology, taxonomy and control of insects and arachnids in an Australasian setting. The purpose of the news bulletin is to provide a medium for both amateur and professional entomologists to record observations, news, views and the results of smaller research projects. Details for the submission of articles are given on the inside back cover. The Entomological Society of New Zealand The Society is a non-profit organisation that exists to foster the science of Entomology in New Zealand, whether in the study of native or adventive fauna. Membership is open to all people interested in the study of insects and related arthropods. Enquiries regarding membership to the Society should be addressed to: Dr Darren F. Ward, Entomological Society Treasurer, New Zealand Arthropod Collection, Landcare Research Private Bag 92170, Auckland 1142, New Zealand [email protected] Officers 2014-2015 President: Dr Stephen Pawson Vice President: Dr Cor Vink Immediate Past President: Dr Phil Lester Secretary: Dr Greg Holwell Treasurer: Dr Matthew Shaw New Zealand Entomologist editor: Dr Phil Sirvid The Weta editor: Dr John Leader Website editor: Dr Sam Brown Visit the website at: http://ento.org.nz/ Fellows of the Entomological Society of New Zealand Dr G. -

ARTHROPODA Subphylum Hexapoda Protura, Springtails, Diplura, and Insects

NINE Phylum ARTHROPODA SUBPHYLUM HEXAPODA Protura, springtails, Diplura, and insects ROD P. MACFARLANE, PETER A. MADDISON, IAN G. ANDREW, JOCELYN A. BERRY, PETER M. JOHNS, ROBERT J. B. HOARE, MARIE-CLAUDE LARIVIÈRE, PENELOPE GREENSLADE, ROSA C. HENDERSON, COURTenaY N. SMITHERS, RicarDO L. PALMA, JOHN B. WARD, ROBERT L. C. PILGRIM, DaVID R. TOWNS, IAN McLELLAN, DAVID A. J. TEULON, TERRY R. HITCHINGS, VICTOR F. EASTOP, NICHOLAS A. MARTIN, MURRAY J. FLETCHER, MARLON A. W. STUFKENS, PAMELA J. DALE, Daniel BURCKHARDT, THOMAS R. BUCKLEY, STEVEN A. TREWICK defining feature of the Hexapoda, as the name suggests, is six legs. Also, the body comprises a head, thorax, and abdomen. The number A of abdominal segments varies, however; there are only six in the Collembola (springtails), 9–12 in the Protura, and 10 in the Diplura, whereas in all other hexapods there are strictly 11. Insects are now regarded as comprising only those hexapods with 11 abdominal segments. Whereas crustaceans are the dominant group of arthropods in the sea, hexapods prevail on land, in numbers and biomass. Altogether, the Hexapoda constitutes the most diverse group of animals – the estimated number of described species worldwide is just over 900,000, with the beetles (order Coleoptera) comprising more than a third of these. Today, the Hexapoda is considered to contain four classes – the Insecta, and the Protura, Collembola, and Diplura. The latter three classes were formerly allied with the insect orders Archaeognatha (jumping bristletails) and Thysanura (silverfish) as the insect subclass Apterygota (‘wingless’). The Apterygota is now regarded as an artificial assemblage (Bitsch & Bitsch 2000). -

Sandra Jones Holdings: Auckland Public Library From

SELECTED REFERENCES Auckland Botanical Society Newsletters (from March 1964) Sandra Jones Holdings: Auckland Public Library from March 1961 (set incomplete) Biological Sciences Library University of Auckland from March 1964 (almost complete) Auckland Institute & Museum Library from Dec 1943 (issue No.1) (set complete) Note: There are two issues dated March 1972 one is actually the July 1972 issue I have indicated this following lists as JUL/MAR 72 BOTANICAL NOTES Acianthus fornicatus var sinclairii unusual form Kauri Grove Adiantum cunninghamii & A. fulvum identification A aethiopicum & A. capillus veneris (introduced) identification A. hispidulum new locality: Te Puke Agathis australis distribution (Arthropodium cirratum) A. australis southern limit Newssheet Aug.78 undated Aristotelia serrata leaf size A. serrata variation of leaf characters Asplenium lamprophyllum new locality: Laingholm Asteliads from N.Z. Jnl of Botany June. 66 Moore) Astelia & Collospermum key Astelia & Collospermum key (supplement to Bot.Soc.Bulletin) Astelia grandis A. nervosa (cockaynei) in Waitakeres Athyrium spp in Waitakeres (Piha Road) A. spp description.(Sep79 Newssheet A. japonicum Morrinsville) Blechnum capense (Green Bay form) at Huia B. capense (Qreen Bay form; localities B. capense .Green Bay form) new locality: Muriwai B. capense/(Green gay form) on Mt Egmont B. vulcanicum new locality: Huia (also B. colensoi at Huia and Mill Bay Bulbophyllum tuberculatum on Pukematekeo Caleana minor name change (see Paracaleana) Calystegia marginata at Whangaruru (Northland Centaurium pink & white forms Cephalotis folllculatus (Albany Pitcher Plant West.Aust Charophytes the NZ.stoneworts Clematis afoliata A year for Clematis Cocos zeylandica Coopers Beach pyrites impregnated Collospermum& Astelia: key Collospermum & Astelia key (supplement to Bot.Soc.Bulletin C. -

Breeding Systems and Reproduction of Indigenous Shrubs in Fragmented

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Breeding systems and reproduction of indigenous shrubs in fragmented ecosystems A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy III Plant Ecology at Massey University by Merilyn F Merrett .. � ... : -- �. � Massey University Palrnerston North, New Zealand 2006 Abstract Sixteen native shrub species with various breeding systems and pollination syndromes were investigated in geographically separated populations to determine breeding systems, reproductive success, population structure, and habitat characteristics. Of the sixteen species, seven are hermaphroditic, seven dioecious, and two gynodioecious. Two of the dioecious species are cryptically dioecious, producing what appear to be perfect, hermaphroditic flowers,but that functionas either male or female. One of the study species, Raukauaanomalus, was thought to be dioecious, but proved to be hermaphroditic. Teucridium parvifolium, was thought to be hermaphroditic, but some populations are gynodioecious. There was variation in self-compatibility among the fo ur AIseuosmia species; two are self-compatible and two are self-incompatible. Self incompatibility was consistent amongst individuals only in A. quercifolia at both study sites, whereas individuals in A. macrophylia ranged from highly self-incompatible to self-compatible amongst fo ur study sites. The remainder of the hermaphroditic study species are self-compatible. Five of the species appear to have dual pollination syndromes, e.g., bird-moth, wind-insect, wind-animal. High levels of pollen limitation were identified in three species at fo ur of the 34 study sites. -

Stitchbird (Hihi), Notiomystis Cincta Recovery Plan

Stitchbird (Hihi), Notiomystis cincta Recovery Plan Threatened Species Recovery plan Series No. 20 Department of Conservation Threatened Species Unit PO Box 10-420 Wellington New Zealand Prepared by: Gretchen Rasch,Shaarina Boyd and Suzanne Clegg for the Threatened Species Unit. April 1996 © Department of Conservation ISSN 1170-3806 ISBN 0-478-01709-6 Cover photo: C.R. Veitch, Department of Conservation CONTENTS page 1. Introduction 1 2. Distribution and Cause of Decline 3 2.1 Past distribution 3 2.2 Present distribution 3 2.3 Possible reasons for decline 3 3. Ecology 7 3.1 Foods and feeding 7 3.2 Competition with other honeyeaters 7 3.3 Habitat 8 4. Recovery to Date 9 4.1 Transferred populations 9 4.2 Captive population 11 5. Recovery Strategy 13 5.1 Long term goal 13 5.2 Short term objectives 13 6. Work Plan 15 6.1 Protect all islands with stitchbirds 15 6.2 Monitor stitchbirds on Little Barrier island 15 6.3 Monitor and (where necessary) enhance stitchbird populations on existing transfer sites 16 6.4 Establish self-sustaining populations of stitchbirds in other locations 18 6.5 Support captive breeding programme 18 6.6 Advocacy 19 6.7 Research needs 20 References 23 Appendices 1. Stitchbird Ecology 2. Criteria for assessing suitability of sites for stitchbird transfer. FIGURES page 1. Present distribution of stitchbird (Notiomystis cincta) 4 2. Average number of stitchbirds counted per transect on Little Barrier Island 1975-1989 5 3. Percentage of food types in stitchbird diet, Little Barrier Island 1982-1984 7 Percentage of foods used by honeyeaters on Little Barrier 1982-1983 Appendix 1, p 1 Nectar used by honeyeaters in the Tirikakawa Valley, Little Barrier 1983-1984 Appendix 1, p2 TABLES page 1. -

Descriptions of Some Mature Kauri Forests of New Zealand, By

DESCRIPTIONS OF SOME MATURE KAURI FORESTS OF NEW ZEALAND by Moinuddin Ahmed and John Ogden Department of Botany, University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, Auckland ABSTRACT A quantitative sampling of 25 mature kauri stands, throughout the species natural limits, was carried out. Each kauri stand is described in terms of its phytosociological attributes (frequency, density and basal area) for kauri and associated canopy and subcanopy species. A species list of plants under 10cm dbh is also given with their relative frequencies in each stand. In all stands kauri comprises most of the basal area. It is associated with 10 different co-dominant species. However, most of the forests have a similar species composition. It is suggested that all these kauri forest samples belong to one overall association. INTRODUCTION The vegetation of various kauri forests has been described by Adam (1889), Cockayne (1908, 1928), Cranwell and Moore (1936), Sexton (1941), Anon (1949) and more recently Barton (1972), Anon (1980) and Ecroyd (1982). A quantitative description of some kauri forests was given by Palmer (1982), Ogden (1983) and Wardle (1984). However, due to extensive past disturbance and milling, most of the above accounts do not describe the natural forest state. Observations on the population dynamics of mature kauri forests were presented by Ahmed and Ogden (1987) and Ogden et al. (1987) while multivariate analyses were performed by Ahmed (1988). However, no comprehensive attempt has yet been made to analyse mature undisturbed kauri forest stands in relation to their species composition. Kauri forests have a restricted distribution in the North Island. Among these remnants, there are few, if any, truly untouched sites. -

In 1987, the Authors Isolated a Ballistospore-Forming Yeast from a Rewarewa Leaf, I.E

J. Gen. App!. Microbiol., 35, 53-58 (1989) BENSINGTONIA INGOLDH SP. NOV., A BAL- LISTOSPORE-FORMING YEAST ISOLATED FROM KNIGHTIA EXCELSA COLLECTED IN NEW ZEALAND TAKASHI NAKASE,* MUTSUMI ITOH, ANDJUNTA SUGIYAMA' Japan Collection of Microorganisms, The Institute of Physical and Chemical Research (RIKEN), Hirosawa 2-1, Wako, Saitama 351-01, Japan The Institute of Applied Microbiology, The University of Tokyo, Yayoi 1-1-1, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113, Japan (Received February 8, 1989) A hitherto undescribed ballistospore-forming yeast was isolated from Knightia excelsa infected by sooty molds collected in New Zealand. It is characterized by ubiquinone-9 and the lack of xylose in the cells so that it is included in the genus Bensingtonia. This yeast resembles B. intermedia and B, yamatoana but is easily distinguished from these two species by the assimilation of nitrate and lactose and the requirement of pyridoxine. Bensingtonia ingoldii Nakase et Itoh sp. nov. is proposed for this yeast. In 1987, the authors isolated a ballistospore-forming yeast from a Rewarewa leaf, i.e. Knightia excelsa (Proteaceae) collected by one of the authors (J. Sugiyama). This strain contains no xylose in the whole cell hydrolyzate and has Q-9 as the major component of ubiquinones so that it is included in the "intermedius group," a group of species having Q-9 in the genus Sporobolomyces. Yamada and Nakagawa (15) found that this yeast is different from any known species of the Q-9- equipped species of Sporobolomyces in the electrophoretic pattern of seven enzymes. In 1988, Nakase and Boekhout (5) emended the diagnosis of the genus Bensingtonia and transferred all of the known Q-9-equipped species of Sporobolomyces into Bensingtonia. -

Carpodetus Serratus

Carpodetus serratus COMMON NAME Putaputaweta, marbleleaf FAMILY Rousseaceae AUTHORITY Carpodetus serratus J.R.Forst. et G.Forst. FLORA CATEGORY Vascular – Native ENDEMIC TAXON Yes ENDEMIC GENUS No ENDEMIC FAMILY Mikimiki, Tararua Forest Park. Jan 1994. No Photographer: Jeremy Rolfe STRUCTURAL CLASS Trees & Shrubs - Dicotyledons NVS CODE CARSER CHROMOSOME NUMBER 2n = 30 CURRENT CONSERVATION STATUS Mikimiki, Tararua Forest Park. Jan 1994. 2012 | Not Threatened Photographer: Jeremy Rolfe PREVIOUS CONSERVATION STATUSES 2009 | Not Threatened 2004 | Not Threatened BRIEF DESCRIPTION Small tree with smallish round or oval distinctively mottled (hence common name) toothed leaves; branchlets zig- zag (particularly when young) DISTRIBUTION Endemic. Widespread. North, South and Stewart Islands. HABITAT Coastal to montane (10-1000 m a.s.l.). Moist broadleaf forest, locally common in beech forest. A frequent component of secondary forest. Streamsides and forest margins. FEATURES Monoecious small tree up to 10 m tall. Trunk slender, bark rough, corky, mottled grey-white, often knobbled due to insect boring. Juvenile plants with distinctive zig-zag branching which is retained to a lesser degree in branchlets of adult. Leaves broad-elliptic to broad-ovate or suborbicular; dark green, marbled; membranous becoming thinly coriaceous; margin serrately toothed; tip acute to obtuse. Juvenile leaves 10-30 mm x 10-20 mm. Adult leaves 40-60 mm x 20-30mm. Petioles c. 10 mm; petioles, peduncles and pedicels pubescent; lenticels prominent. Flowers in panicles at branchlet tips; panicles to 50 x 50 mm; flowers 5-6 mm diam.; calyx lobes c. 1 mm long, triangular- attenuate; petals white, ovate, acute, 3-4 mm long. Stamens 5-6, alternating with petals; filaments short.