An Education Resource for Schools: Part Three: Plants Pages 142-165

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 17 Hyperlinks

1ISSUE 17 | WINTER 2016 PlUS oN PagE 16 oRdER yoUR 2017 Astonishing calENdaR NoW 2017 Calendar puriri moth SPONSORED BY alSo IN ThIS ISSUE: MESMERISEd by MoNaRchS | dElIghTfUl dahlIaS | MEMoRIES To TREaSURE 2 I am sure you will be fascinated by our puriri moth featuring in this issue. Not From the many people realise that they take about five years from egg to adult… and then Editor live for about 48 hours! If you haven’t got dahlias growing idwinter usually means in your garden, you’ll change a dearth of butterflies your mind when you read CoNtENtS M but this year has certainly not our gardening feature. As well, Brian Cover photo: Nicholas A Martin been typical. At Te Puna Quarry Park Patrick tells of another fascinating moth. there are hundreds (yes, hundreds) of We are very excited about events that 2 Editorial monarch caterpillars and pupae. In my are coming up: not only our plans for our garden my nettles are covered with beautiful forest ringlet but our presence hundreds (yes, hundreds) of admiral at two major shows in Auckland in 3 Certification larvae in their little tent cocoons, November. Thanks to the Body Shop overwintering. My midwinter nectar is On another note, we have plans covered in monarchs, still mating and for rolling out the movie Flight of the 4-5 Ghosts Moths & egg-laying. It could make for a very busy, Butterflies in 3D to a cinema near you. early spring! Because it will be another three months Puriri Moths One of the best parts of my work for before our next magazine we urge you the MBNZT is seeing people’s delight to sign up for our e-news (free) to keep 6 The Trust at Work at a butterfly release. -

Trees for the Land

Trees for the Land GROWING TREES IN NORTHLAND FOR PROTECTION, PRODUCTION AND PLEASURE FOREWORD Trees are an integral, highly visible and valuable part of the Northland landscape. While many of us may not give much thought to the many and varied roles of trees in our lives, our reliance on them can not be overstated. Both native and exotic tree species make important contributions to our region – environmentally, socially, culturally and economically. Pohutukawa – a coastal icon – line our coasts and are much loved and appreciated by locals and tourists alike. Similarly, many of the visitors who come here do not consider their trip complete without a journey to view the giant and majestic kauri of Waipoua, which are of huge importance to Mäori. Many Northlanders make their livings working in the forest industry or other industries closely aligned to it and trees also play a crucial role environmentally. When all these factors are considered, it makes sense that wise land management should include the planting of a variety of tree species, particularly since Northland is an erosion- prone area. Trees help stabilise Northland’s hillsides and stream banks. They help control winter flood flows and provide shelter and shade for the land, rivers and stock. They also provide valuable shelter, protection and food for Northland’s flora and fauna. This publication draws together tree planting information and advice from a wide range of sources into one handy guide. It has been written specifically for Northlanders and recommends trees that will survive well in our sometimes demanding climate. The Northland Regional Council is committed to the sustainable management and development of natural resources like our trees. -

THE WETA News Bulletin of the ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY of NEW ZEALAND

THE WETA News Bulletin of THE ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF NEW ZEALAND Volume 47 July 2014 ISSN 0111-7696 THE WETA News Bulletin of the Entomological Society of New Zealand (Inc.) [Now ONLINE at http://ento.org.nz/nzentomologist/index.php] Aims and Scope The Weta is the news bulletin of the Entomological Society of New Zealand. The Weta, like the society’s journal, the New Zealand Entomologist, promotes the study of the biology, ecology, taxonomy and control of insects and arachnids in an Australasian setting. The purpose of the news bulletin is to provide a medium for both amateur and professional entomologists to record observations, news, views and the results of smaller research projects. Details for the submission of articles are given on the inside back cover. The Entomological Society of New Zealand The Society is a non-profit organisation that exists to foster the science of Entomology in New Zealand, whether in the study of native or adventive fauna. Membership is open to all people interested in the study of insects and related arthropods. Enquiries regarding membership to the Society should be addressed to: Dr Darren F. Ward, Entomological Society Treasurer, New Zealand Arthropod Collection, Landcare Research Private Bag 92170, Auckland 1142, New Zealand [email protected] Officers 2014-2015 President: Dr Stephen Pawson Vice President: Dr Cor Vink Immediate Past President: Dr Phil Lester Secretary: Dr Greg Holwell Treasurer: Dr Matthew Shaw New Zealand Entomologist editor: Dr Phil Sirvid The Weta editor: Dr John Leader Website editor: Dr Sam Brown Visit the website at: http://ento.org.nz/ Fellows of the Entomological Society of New Zealand Dr G. -

ARTHROPODA Subphylum Hexapoda Protura, Springtails, Diplura, and Insects

NINE Phylum ARTHROPODA SUBPHYLUM HEXAPODA Protura, springtails, Diplura, and insects ROD P. MACFARLANE, PETER A. MADDISON, IAN G. ANDREW, JOCELYN A. BERRY, PETER M. JOHNS, ROBERT J. B. HOARE, MARIE-CLAUDE LARIVIÈRE, PENELOPE GREENSLADE, ROSA C. HENDERSON, COURTenaY N. SMITHERS, RicarDO L. PALMA, JOHN B. WARD, ROBERT L. C. PILGRIM, DaVID R. TOWNS, IAN McLELLAN, DAVID A. J. TEULON, TERRY R. HITCHINGS, VICTOR F. EASTOP, NICHOLAS A. MARTIN, MURRAY J. FLETCHER, MARLON A. W. STUFKENS, PAMELA J. DALE, Daniel BURCKHARDT, THOMAS R. BUCKLEY, STEVEN A. TREWICK defining feature of the Hexapoda, as the name suggests, is six legs. Also, the body comprises a head, thorax, and abdomen. The number A of abdominal segments varies, however; there are only six in the Collembola (springtails), 9–12 in the Protura, and 10 in the Diplura, whereas in all other hexapods there are strictly 11. Insects are now regarded as comprising only those hexapods with 11 abdominal segments. Whereas crustaceans are the dominant group of arthropods in the sea, hexapods prevail on land, in numbers and biomass. Altogether, the Hexapoda constitutes the most diverse group of animals – the estimated number of described species worldwide is just over 900,000, with the beetles (order Coleoptera) comprising more than a third of these. Today, the Hexapoda is considered to contain four classes – the Insecta, and the Protura, Collembola, and Diplura. The latter three classes were formerly allied with the insect orders Archaeognatha (jumping bristletails) and Thysanura (silverfish) as the insect subclass Apterygota (‘wingless’). The Apterygota is now regarded as an artificial assemblage (Bitsch & Bitsch 2000). -

Carpodetus Serratus

Carpodetus serratus COMMON NAME Putaputaweta, marbleleaf FAMILY Rousseaceae AUTHORITY Carpodetus serratus J.R.Forst. et G.Forst. FLORA CATEGORY Vascular – Native ENDEMIC TAXON Yes ENDEMIC GENUS No ENDEMIC FAMILY Mikimiki, Tararua Forest Park. Jan 1994. No Photographer: Jeremy Rolfe STRUCTURAL CLASS Trees & Shrubs - Dicotyledons NVS CODE CARSER CHROMOSOME NUMBER 2n = 30 CURRENT CONSERVATION STATUS Mikimiki, Tararua Forest Park. Jan 1994. 2012 | Not Threatened Photographer: Jeremy Rolfe PREVIOUS CONSERVATION STATUSES 2009 | Not Threatened 2004 | Not Threatened BRIEF DESCRIPTION Small tree with smallish round or oval distinctively mottled (hence common name) toothed leaves; branchlets zig- zag (particularly when young) DISTRIBUTION Endemic. Widespread. North, South and Stewart Islands. HABITAT Coastal to montane (10-1000 m a.s.l.). Moist broadleaf forest, locally common in beech forest. A frequent component of secondary forest. Streamsides and forest margins. FEATURES Monoecious small tree up to 10 m tall. Trunk slender, bark rough, corky, mottled grey-white, often knobbled due to insect boring. Juvenile plants with distinctive zig-zag branching which is retained to a lesser degree in branchlets of adult. Leaves broad-elliptic to broad-ovate or suborbicular; dark green, marbled; membranous becoming thinly coriaceous; margin serrately toothed; tip acute to obtuse. Juvenile leaves 10-30 mm x 10-20 mm. Adult leaves 40-60 mm x 20-30mm. Petioles c. 10 mm; petioles, peduncles and pedicels pubescent; lenticels prominent. Flowers in panicles at branchlet tips; panicles to 50 x 50 mm; flowers 5-6 mm diam.; calyx lobes c. 1 mm long, triangular- attenuate; petals white, ovate, acute, 3-4 mm long. Stamens 5-6, alternating with petals; filaments short. -

Invertebrate Fauna of 4 Tree Species

MOEED AND MEADS: INVERTEBRATE FAUNA OF FOUR TREE SPECIES 39 INVERTEBRATE FAUNA OF FOUR TREE SPECIES IN ORONGORONGO VALLEY, NEW ZEALAND, AS REVEALED BY TRUNK TRAPS ABDUL MOEED AND M. J. MEADS Ecology Division, D.S.I.R., Private Bag, Lower Hutt, New Zealand. SUMMARY: Tree trunks are important links between the forest floor and canopy, especially for flightless invertebrates that move from the forest floor to feed or breed in the canopy. Traps were used to sample invertebrates moving up and down on mahoe (Melicytus ramiflorus), hinau (Elaeocarpus dentatus), hard beech (Nothofagus truncata), and kamahi (Weinmannia racemosa). In 19 months 22 696 invertebrates were collected. Many unexpected groups e.g. ground wetas, ground beetles, some caterpillars, amphipods, spring-tails, mites, peri- patus, and earthworms were caught in up-traps 1.5 m above ground. Overall, up-traps caught more (80%) invertebrates than down-traps (20%) and 16 of 29 groups of invertebrates were caught more often in up-traps. Fewer invertebrates were caught on hard beech than on hinau with comparable catching surface area. The numbers of spiders caught were significantly corre- lated with tree circumference. The invertebrates caught fell broadly into 3 trophic levels-most were saprophytes, with equal numbers of herbivores and predators. Perched leaf litter in epiphytes and in tree cavities contain invertebrates otherwise associated with the forest floor. Invertebrates in the lowland forests of New Zealand appear to be generalists in their use of habitats (as many of them are saprophytes and predators). KEYWORDS: Trunk trap; forest; invertebrates; arboreal fauna; Melicytus ramiflorus; Elaeocarpus dentatus; Notho- fagus truncata; Weinmannia racemosa; Orongorongo Valley, New Zealand. -

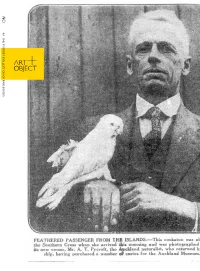

Auckland Like Many Other Lay Enthusiasts, He Made Considerable

49 THE PYCROFT COLLECTION OF RARE BOOKS Arthur Thomas Pycroft ART + OBJECT (1875–1971) 3 Abbey Street Arthur Pycroft was the “essential gentleman amateur”. Newton Auckland Like many other lay enthusiasts, he made considerable PO Box 68 345 contributions as a naturalist, scholar, historian and Newton conservationist. Auckland 1145 He was educated at the Church of England Grammar Telephone: +64 9 354 4646 School in Parnell, Auckland’s first grammar school, where his Freephone: 0 800 80 60 01 father Henry Thomas Pycroft a Greek and Hebrew scholar Facsimile: +64 9 354 4645 was the headmaster between 1883 and 1886. The family [email protected] lived in the headmaster’s residence now known as “Kinder www.artandobject.co.nz House”. He then went on to Auckland Grammar School. On leaving school he joined the Auckland Institute in 1896, remaining a member Previous spread: for 75 years, becoming President in 1935 and serving on the Council for over 40 years. Lots, clockwise from top left: 515 Throughout this time he collaborated as a respected colleague with New Zealand’s (map), 521, 315, 313, 513, 507, foremost men of science, naturalists and museum directors of his era. 512, 510, 514, 518, 522, 520, 516, 519, 517 From an early age he developed a “hands on” approach to all his interests and corresponded with other experts including Sir Walter Buller regarding his rediscovery Rear cover: of the Little Black Shag and other species which were later included in Buller’s 1905 Lot 11 Supplement. New Zealand’s many off shore islands fascinated him and in the summer of 1903-04 he spent nearly six weeks on Taranga (Hen Island), the first of several visits. -

Automated System for Recording Emerging Puriri Moths, Aenetus Virescens (Hepialidae: Lepidoptera)

6 The Weta 39:6-11 (2010) Automated system for recording emerging puriri moths, Aenetus virescens (Hepialidae: Lepidoptera) Peter McKenzie Nga Manu Nature Reserve, PO Box 126, Waikanae, New Zealand([email protected]) Introduction The puriri moth, Aenetus virescens (Doubleday, 1843) is a widespread forest species in the North Island of New Zealand (Dugdale 1994). Eggs are deposited on the forest floor where early instars feed on fungi growing on dead wood or emergent polypore fruiting bodies, such as bracket fungi, for about three months. They then transition to boring into various trees and shrubs where they feed on callus tissue around the entrance of tunnels that extend into the wood (Grehan, 1987a). Larval and pupal development varies from one to four years in putaputaweta (Carpodetus serratus), and may be even longer on other hosts and localities (Grehan 1987b). Prior to pupation, the larva dismantles the central region of the silk web covering the feeding area around the tunnel, sometimes resulting in a perforated appearance. Most adults emerge in the spring months of September-November with another smaller peak sometimes occurring in March. Emergent adults may be found resting by their tunnels in the late afternoon from at least 2.00 pm (1400 hrs) and before nightfall. This is probably a general feature of wood-boring Hepialidae as it has been reported in Zelotypia and other species of Aenetus Grehan (1987b) and also in the South American Phassus emerging 1400-1700 hrs (Schaus 1888). Grehan (1987b) attempted to observe adult emergence by searching host trees in the afternoon but the only specimens found had already emerged and were resting on the host trunk. -

Ecological Restoration of New Zealand Islands

CONTENTS Introduction D.R. Towns, I.A.E. Atkinson, and C.H. Daugherty .... ... .. .... .. .... ... .... ... .... .... iii SECTION I: RESOURCES AND MANAGEMENT New Zealand as an archipelago: An international perspective Jared M. Diamond . 3 The significance of the biological resources of New Zealand islands for ecological restoration C.H. Daugherty, D.R. Towns, I.A.E. Atkinson, G.W. Gibbs . 9 The significance of island reserves for ecological restoration of marine communities W.J.Ballantine. 22 Reconstructing the ambiguous: Can island ecosystems be restored? Daniel Simberloff. 37 How representative can restored islands really be? An analysis of climo-edaphic environments in New Zealand Colin D. Meurk and Paul M. Blaschke . 52 Ecological restoration on islands: Prerequisites for success I.A.E Atkinson . 73 The potential for ecological restoration in the Mercury Islands D.R. Towns, I.A.E. Atkinson, C.H. Daugherty . 91 Motuhora: A whale of an island S. Smale and K. Owen . ... ... .. ... .... .. ... .. ... ... ... ... ... .... ... .... ..... 109 Mana Island revegetation: Data from late Holocene pollen analysis P.I. Chester and J.I. Raine ... ... ... .... .... ... .. ... .. .... ... .... .. .... ..... 113 The silent majority: A plea for the consideration of invertebrates in New Zealand island management - George W. Gibbs .. ... .. ... .. .... ... .. .... ... .. ... ... ... ... .... ... ..... ..... 123 Community effects of biological introductions and their implications for restoration Daniel Simberloff . 128 Eradication of introduced animals from the islands of New Zealand C.R. Veitch and Brian D. Bell . 137 Mapara: Island management "mainland" style Alan Saunders . 147 Key archaeological features of the offshore islands of New Zealand Janet Davidson . .. ... ... ... .. ... ... .. .... ... .. ... .. .... .. ..... .. .... ...... 150 Potential for ecological restoration of islands for indigenous fauna and flora John L. Craig .. .. ... .. ... ... ... .... .. ... ... .. ... .. .... ... ... .... .... ..... .. 156 Public involvement in island restoration Mark Bellingham . -

Name Suburb Notes a Abbotleigh Avenue Te Atatu Peninsula Named C.1957. Houses Built 1957. Source: Geomaps Aerial Photo 1959

Name Suburb Notes A Abbotleigh Avenue Te Atatu Peninsula Named c.1957. Houses built 1957. Source: Geomaps aerial photo 1959. Abel Tasman Ave Henderson Named 7/8/1973. Originally named Tasman Ave. Name changed to avoid confusion with four other Auckland streets. Abel Janszoon Tasman (1603-1659) was a Dutch navigator credited with being the discoverer of NZ in 1642. Located off Lincoln Rd. Access Road Kumeu Named between 1975-1991. Achilles Street New Lynn Named between 1943 and 1961. H.M.S. Achilles ship. Previously Rewa Rewa Street before 1930. From 1 March 1969 it became Hugh Brown Drive. Acmena Ave Waikumete Cemetery Named between 1991-2008. Adam Sunde Place Glen Eden West Houses built 1983. Addison Drive Glendene Houses built 1969. Off Hepburn Rd. Aditi Close Massey Formed 2006. Previously bush in 2001. Source: Geomaps aerial photo 2006. Adriatic Avenue Henderson Named c.1958. Geomaps aerial photo 1959. Subdivision of Adriatic Vineyard, which occupied 15 acres from corner of McLeod and Gt Nth Rd. The Adriatic is the long arm of the Mediterranean Sea which separates Italy from Yugoslavia and Albania. Aetna Place McLaren Park Named between 1975-1983. Located off Heremaia St. Subdivision of Public Vineyard. Source: Geomaps aerial photo 1959. Afton Place Ranui Houses built 1979. Agathis Rise Waikumete Cemetery Named between 1991-2008. Agathis australis is NZ kauri Ahu Ahu Track Karekare Named before 2014. The track runs from a bend in Te Ahu Ahu Road just before the A- frame house. The track follows the old bridle path on a steeply graded descent to Watchman Road. -

Ecology of Vascular Epiphytes in Urban Forests with Special Reference to the Shrub Epiphyte Griselinia Lucida

Ecology of vascular epiphytes in urban forests with special reference to the shrub epiphyte Griselinia lucida A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Biological Sciences at The University of Waikato by Catherine Louise Bryan 2011 Abstract This research investigated the ecology of vascular epiphytes and vines in the Waikato region of the North Island, and the water relations of the shrub hemiepiphyte Griselinia lucida. The main goal was to develop robust recommendations for the inclusion of epiphytic species in urban forest restoration projects. To achieve this, three broad questions were addressed: 1. How are vascular epiphytes and vines distributed throughout the nonurban and urban areas of the Waikato region, and how does this compare to other North Island areas? 2. Why are some epiphyte and vine species absent from urban Hamilton and what opportunities exist for their inclusion in restoration projects? 3. How does Griselinia lucida respond to desiccation stress and how does this compare to its congener G. littoralis? To investigate questions one and two, an ecological survey of the epiphyte communities on host trees in Waikato (n=649) and Taranaki (n=101) was conducted, alongside canopy microclimate monitoring in five Waikato sites. Results show that epiphyte and vine populations in Hamilton City forests represent only 55.2 % of the total Waikato species pool, and have a very low average of 0.8 epiphyte species per host. In contrast, the urban forests of Taranaki support 87.9 % of the local species pool and have an average of 5.5 species per host tree. -

Introduced Pests

Introduced pests Learning outcomes Using examples of pests (possums and rats) students will investigate the effect of the pest on Kapiti’s flora and fauna, the methods used for their eradication and the effect of the eradication. Links can be made to: Science: Making Sense of the Living World Students can: L 5.4 Research a national environmental issue and explain the need for responsible and co- operative guardianship of New Zealand’s environment L 6. 4 Investigate a New Zealand example of how people apply biological principles to plant and animal management English Links can be made to Oral Language: Listening and speaking functions and Written Language: Reading and Writing functions. Pre-visit: Learning about the Environment Teachers will need: TV monitor and video player. Sticky labels Resources in kit (red dot) Video: Wild South ’Sanctuary’ (approx 30-min. long—particularly first 15 min.) Species cards Posters Response of forest birds to rat eradication on Kapiti Island Eradication of possums from Kapiti Island Books – Restoring Kapiti Edited by Kerry Brown (photocopy of chapters on possum and rat eradication) – Recovery of the vegetation following possum reductions (extract from report) Photographs Newspaper articles Species fact sheets Fact Sheet: Key facts about rodent prevention in the Kapiti Island area Students can: Discuss what they know about animal pests in New Zealand. Consider which mammals are pests in New Zealand native ecosystems and what effect they have. Watch the first 17 minutes of video Wild South ‘Sanctuary’. Note that rats were removed after the video was made. Discuss the effects possums had on Kapiti Island ecosystems, the methods they used to eradicate possums and the effect of the eradication.