Behaviour and Activity Budgeting of Reproductive Kiwi in a Fenced Population

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trees for the Land

Trees for the Land GROWING TREES IN NORTHLAND FOR PROTECTION, PRODUCTION AND PLEASURE FOREWORD Trees are an integral, highly visible and valuable part of the Northland landscape. While many of us may not give much thought to the many and varied roles of trees in our lives, our reliance on them can not be overstated. Both native and exotic tree species make important contributions to our region – environmentally, socially, culturally and economically. Pohutukawa – a coastal icon – line our coasts and are much loved and appreciated by locals and tourists alike. Similarly, many of the visitors who come here do not consider their trip complete without a journey to view the giant and majestic kauri of Waipoua, which are of huge importance to Mäori. Many Northlanders make their livings working in the forest industry or other industries closely aligned to it and trees also play a crucial role environmentally. When all these factors are considered, it makes sense that wise land management should include the planting of a variety of tree species, particularly since Northland is an erosion- prone area. Trees help stabilise Northland’s hillsides and stream banks. They help control winter flood flows and provide shelter and shade for the land, rivers and stock. They also provide valuable shelter, protection and food for Northland’s flora and fauna. This publication draws together tree planting information and advice from a wide range of sources into one handy guide. It has been written specifically for Northlanders and recommends trees that will survive well in our sometimes demanding climate. The Northland Regional Council is committed to the sustainable management and development of natural resources like our trees. -

Patterns of Flammability Across the Vascular Plant Phylogeny, with Special Emphasis on the Genus Dracophyllum

Lincoln University Digital Thesis Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: you will use the copy only for the purposes of research or private study you will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of the thesis and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate you will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from the thesis. Patterns of flammability across the vascular plant phylogeny, with special emphasis on the genus Dracophyllum A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of philosophy at Lincoln University by Xinglei Cui Lincoln University 2020 Abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of philosophy. Abstract Patterns of flammability across the vascular plant phylogeny, with special emphasis on the genus Dracophyllum by Xinglei Cui Fire has been part of the environment for the entire history of terrestrial plants and is a common disturbance agent in many ecosystems across the world. Fire has a significant role in influencing the structure, pattern and function of many ecosystems. Plant flammability, which is the ability of a plant to burn and sustain a flame, is an important driver of fire in terrestrial ecosystems and thus has a fundamental role in ecosystem dynamics and species evolution. However, the factors that have influenced the evolution of flammability remain unclear. -

Sandra Jones Holdings: Auckland Public Library From

SELECTED REFERENCES Auckland Botanical Society Newsletters (from March 1964) Sandra Jones Holdings: Auckland Public Library from March 1961 (set incomplete) Biological Sciences Library University of Auckland from March 1964 (almost complete) Auckland Institute & Museum Library from Dec 1943 (issue No.1) (set complete) Note: There are two issues dated March 1972 one is actually the July 1972 issue I have indicated this following lists as JUL/MAR 72 BOTANICAL NOTES Acianthus fornicatus var sinclairii unusual form Kauri Grove Adiantum cunninghamii & A. fulvum identification A aethiopicum & A. capillus veneris (introduced) identification A. hispidulum new locality: Te Puke Agathis australis distribution (Arthropodium cirratum) A. australis southern limit Newssheet Aug.78 undated Aristotelia serrata leaf size A. serrata variation of leaf characters Asplenium lamprophyllum new locality: Laingholm Asteliads from N.Z. Jnl of Botany June. 66 Moore) Astelia & Collospermum key Astelia & Collospermum key (supplement to Bot.Soc.Bulletin) Astelia grandis A. nervosa (cockaynei) in Waitakeres Athyrium spp in Waitakeres (Piha Road) A. spp description.(Sep79 Newssheet A. japonicum Morrinsville) Blechnum capense (Green Bay form) at Huia B. capense (Qreen Bay form; localities B. capense .Green Bay form) new locality: Muriwai B. capense/(Green gay form) on Mt Egmont B. vulcanicum new locality: Huia (also B. colensoi at Huia and Mill Bay Bulbophyllum tuberculatum on Pukematekeo Caleana minor name change (see Paracaleana) Calystegia marginata at Whangaruru (Northland Centaurium pink & white forms Cephalotis folllculatus (Albany Pitcher Plant West.Aust Charophytes the NZ.stoneworts Clematis afoliata A year for Clematis Cocos zeylandica Coopers Beach pyrites impregnated Collospermum& Astelia: key Collospermum & Astelia key (supplement to Bot.Soc.Bulletin C. -

Breeding Systems and Reproduction of Indigenous Shrubs in Fragmented

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Breeding systems and reproduction of indigenous shrubs in fragmented ecosystems A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy III Plant Ecology at Massey University by Merilyn F Merrett .. � ... : -- �. � Massey University Palrnerston North, New Zealand 2006 Abstract Sixteen native shrub species with various breeding systems and pollination syndromes were investigated in geographically separated populations to determine breeding systems, reproductive success, population structure, and habitat characteristics. Of the sixteen species, seven are hermaphroditic, seven dioecious, and two gynodioecious. Two of the dioecious species are cryptically dioecious, producing what appear to be perfect, hermaphroditic flowers,but that functionas either male or female. One of the study species, Raukauaanomalus, was thought to be dioecious, but proved to be hermaphroditic. Teucridium parvifolium, was thought to be hermaphroditic, but some populations are gynodioecious. There was variation in self-compatibility among the fo ur AIseuosmia species; two are self-compatible and two are self-incompatible. Self incompatibility was consistent amongst individuals only in A. quercifolia at both study sites, whereas individuals in A. macrophylia ranged from highly self-incompatible to self-compatible amongst fo ur study sites. The remainder of the hermaphroditic study species are self-compatible. Five of the species appear to have dual pollination syndromes, e.g., bird-moth, wind-insect, wind-animal. High levels of pollen limitation were identified in three species at fo ur of the 34 study sites. -

Stitchbird (Hihi), Notiomystis Cincta Recovery Plan

Stitchbird (Hihi), Notiomystis cincta Recovery Plan Threatened Species Recovery plan Series No. 20 Department of Conservation Threatened Species Unit PO Box 10-420 Wellington New Zealand Prepared by: Gretchen Rasch,Shaarina Boyd and Suzanne Clegg for the Threatened Species Unit. April 1996 © Department of Conservation ISSN 1170-3806 ISBN 0-478-01709-6 Cover photo: C.R. Veitch, Department of Conservation CONTENTS page 1. Introduction 1 2. Distribution and Cause of Decline 3 2.1 Past distribution 3 2.2 Present distribution 3 2.3 Possible reasons for decline 3 3. Ecology 7 3.1 Foods and feeding 7 3.2 Competition with other honeyeaters 7 3.3 Habitat 8 4. Recovery to Date 9 4.1 Transferred populations 9 4.2 Captive population 11 5. Recovery Strategy 13 5.1 Long term goal 13 5.2 Short term objectives 13 6. Work Plan 15 6.1 Protect all islands with stitchbirds 15 6.2 Monitor stitchbirds on Little Barrier island 15 6.3 Monitor and (where necessary) enhance stitchbird populations on existing transfer sites 16 6.4 Establish self-sustaining populations of stitchbirds in other locations 18 6.5 Support captive breeding programme 18 6.6 Advocacy 19 6.7 Research needs 20 References 23 Appendices 1. Stitchbird Ecology 2. Criteria for assessing suitability of sites for stitchbird transfer. FIGURES page 1. Present distribution of stitchbird (Notiomystis cincta) 4 2. Average number of stitchbirds counted per transect on Little Barrier Island 1975-1989 5 3. Percentage of food types in stitchbird diet, Little Barrier Island 1982-1984 7 Percentage of foods used by honeyeaters on Little Barrier 1982-1983 Appendix 1, p 1 Nectar used by honeyeaters in the Tirikakawa Valley, Little Barrier 1983-1984 Appendix 1, p2 TABLES page 1. -

Descriptions of Some Mature Kauri Forests of New Zealand, By

DESCRIPTIONS OF SOME MATURE KAURI FORESTS OF NEW ZEALAND by Moinuddin Ahmed and John Ogden Department of Botany, University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, Auckland ABSTRACT A quantitative sampling of 25 mature kauri stands, throughout the species natural limits, was carried out. Each kauri stand is described in terms of its phytosociological attributes (frequency, density and basal area) for kauri and associated canopy and subcanopy species. A species list of plants under 10cm dbh is also given with their relative frequencies in each stand. In all stands kauri comprises most of the basal area. It is associated with 10 different co-dominant species. However, most of the forests have a similar species composition. It is suggested that all these kauri forest samples belong to one overall association. INTRODUCTION The vegetation of various kauri forests has been described by Adam (1889), Cockayne (1908, 1928), Cranwell and Moore (1936), Sexton (1941), Anon (1949) and more recently Barton (1972), Anon (1980) and Ecroyd (1982). A quantitative description of some kauri forests was given by Palmer (1982), Ogden (1983) and Wardle (1984). However, due to extensive past disturbance and milling, most of the above accounts do not describe the natural forest state. Observations on the population dynamics of mature kauri forests were presented by Ahmed and Ogden (1987) and Ogden et al. (1987) while multivariate analyses were performed by Ahmed (1988). However, no comprehensive attempt has yet been made to analyse mature undisturbed kauri forest stands in relation to their species composition. Kauri forests have a restricted distribution in the North Island. Among these remnants, there are few, if any, truly untouched sites. -

In 1987, the Authors Isolated a Ballistospore-Forming Yeast from a Rewarewa Leaf, I.E

J. Gen. App!. Microbiol., 35, 53-58 (1989) BENSINGTONIA INGOLDH SP. NOV., A BAL- LISTOSPORE-FORMING YEAST ISOLATED FROM KNIGHTIA EXCELSA COLLECTED IN NEW ZEALAND TAKASHI NAKASE,* MUTSUMI ITOH, ANDJUNTA SUGIYAMA' Japan Collection of Microorganisms, The Institute of Physical and Chemical Research (RIKEN), Hirosawa 2-1, Wako, Saitama 351-01, Japan The Institute of Applied Microbiology, The University of Tokyo, Yayoi 1-1-1, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113, Japan (Received February 8, 1989) A hitherto undescribed ballistospore-forming yeast was isolated from Knightia excelsa infected by sooty molds collected in New Zealand. It is characterized by ubiquinone-9 and the lack of xylose in the cells so that it is included in the genus Bensingtonia. This yeast resembles B. intermedia and B, yamatoana but is easily distinguished from these two species by the assimilation of nitrate and lactose and the requirement of pyridoxine. Bensingtonia ingoldii Nakase et Itoh sp. nov. is proposed for this yeast. In 1987, the authors isolated a ballistospore-forming yeast from a Rewarewa leaf, i.e. Knightia excelsa (Proteaceae) collected by one of the authors (J. Sugiyama). This strain contains no xylose in the whole cell hydrolyzate and has Q-9 as the major component of ubiquinones so that it is included in the "intermedius group," a group of species having Q-9 in the genus Sporobolomyces. Yamada and Nakagawa (15) found that this yeast is different from any known species of the Q-9- equipped species of Sporobolomyces in the electrophoretic pattern of seven enzymes. In 1988, Nakase and Boekhout (5) emended the diagnosis of the genus Bensingtonia and transferred all of the known Q-9-equipped species of Sporobolomyces into Bensingtonia. -

Appendix A: New Zealand Plant Availability in Australian Nurseries NB: the Following Is a Selection of Most-Commonly Seen Species

Appendix A: New Zealand Plant availability in Australian nurseries NB: the following is a selection of most-commonly seen species. Many more could be added that were here (from nursery catalogues) that are seldom seen now. Botanic Name Common name Date(s) Introduced? Acaena sp., e.g. A. sangisorbae bidi bidi/ NZ burr 1866 NSW; 1860 Vic; Adiantum cunninghamii common (NZ)/ Cunningham’s maidenhair 1869 Tas., 1877 Vic. fern Agathis australis NZ kauri 1843 NSW; 1857 SA; pre-1857 Tas., 1855 Vic. (1823 was in Europe) Alectryon excelsus titoki /NZ ash 1864 Vic. Alseuosmia quercifolia Karapapa 1869 Tas. Aristotelia serrata makomako / wine berry 1857-74 Tas., c.1879 Vic. Arthropodium cirrhatum renga renga / Cape Reinga lily 1843 NSW; 1860/73 Vic. (1821 in UK) Asplenium bulbiferum ‘New Zealand mana mana / hen-and-chickens fern 1886 Vic. var.’ A. banksii c.1853 UK; pre-1857 Tas., 1860 Vic. Astelia chathamica ‘Silver Spear’ Chatham Island kakaha / bush flax Species: 1934/66. ‘Silver Spear’ released 1976 NZ (DD). On an 1984 IUCN list of threatened species Astelia nervosa kakaha / bush flax c.1770 UK; c.1898 Vic? Beilschmedia tawa Tawa 1769 NZ; ? Blechnum banksii fern (W.Coast NZ) 1889 Vic. B. capense kio kio / Cape fern 1873 Vic. B. chambersii fern 1873 Vic. B. discolor piu piu / crown fern 1873 Vic. B. fraseri fern 1889 Vic. B. nigrum black blechnum 1889 Vic. B. vulcanicum fern 1886 Vic. Brachyglottis (syn.Senecio) greyi Grey’s groundsel B. monroi Monro’s groundsel B. repanda rangiora / bush man’s toilet paper 1769 NZ; Pre-1857 Tas., 1860 Vic. -

University of Auckland Research Repository, Researchspace

Libraries and Learning Services University of Auckland Research Repository, ResearchSpace Suggested Reference Ryder, J. M., & Burns, B. R. (2016). What is the host range of Phytophthora agathidicida in New Zealand. Poster session presented at the meeting of New Zealand Plant Protection Vol. 69. Palmerston North. https://www.nzpps.org/nzpp_abstract.php?paper=693201 Copyright Items in ResearchSpace are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise indicated. Previously published items are made available in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher. For more information, see General copyright. What is the host range of Phytophthora agathidicida (kauri dieback disease) in Jessica M. Ryder 1, Nick W. Waipara 2, Bruce R. Burns 1 New Zealand? 1 School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland 2 Auckland Council J M Ryder , Email: [email protected], ph: 021 2516036. B R Burns, Email: [email protected], ph: 027 280 8332 N W Waipara, Email: [email protected], ph: 021 2229067 Field Study: investigating the vegetation composition of kauri forest infected Figure.2 Ordination of with P. agathidicida, versus kauri forest free from P. agathidicida infected (red) and healthy (blue) sites when similarity of species abundances at • Recce surveys were carried out within the Waitakere Ranges in each site were West Auckland in infected and healthy kauri stands. Recording compared. plant species abundances, along with many environmental Figure.3 Analysis of characteristics. similarities for the null • Ordination results showed a clear separation of infected versus hypothesis that there are healthy sites (Figure.2), shows infected sites are more similar in no differences between healthy and infected sites. -

Effects of Ungulates on Structure and Species Composition in The

R. B. ALLEN1, I. J. PAYTON1 AND J. E. KNOWLTON2 119 1. Forest Research Institute, P.O. Box 31-011, Christchurch, New Zealand 2. New Zealand Forest Service, P.O. Box 1340, Rotorua, New Zealand. EFFECTS OF UNGULATES ON STRUCTURE AND SPECIES COMPOSITION IN THE UREWERA FORESTS AS SHOWN BY EXCLOSURES Summary: Seventeen exclosures were built by the New Zealand Forest Service within Urewera forests over the period 1961-68 to exclude ungulates. Forest structure and species composition inside and outside these exclosures were compared in 1980-81. Some relatively shade tolerant species such as the fern Asplenium bulbiferum, the liane Ripogonum scandens, the sub-canopy shrubs Geniostoma ligustrifolium and Coprosma australis and the canopy species Beilschmiedia tawa were less abundant in certain tiers outside the exclosures than inside. By contrast, only a few species were more abundant outside then inside the exclosures. These included the unpalatable shrub Pseudowintera colorata, turf-forming Uncinia species and Cardamine debilis. Overall density and species richness for small diametered trees and for the sapling tier were lower outside the exclosures than inside. Despite the large reduction in ungulate numbers throughout Urewera forests these introduced browsing animals, particularly deer, still affect the structure and composition of most forest types. Keywords: regeneration; forest; introduced animals; ungulates; deer, Cervus sp., Cervidae; exclosure; Urewera; New Zealand. Introduction however, apparently anomolous species The Urewera forests cover about 400 000 ha of distributions, not fully adjusted to altitude, have steep highlands, of which approximately half lie been explained in terms of recent volcanic activity within Urewera National Park (McKelvey, 1973). -

Knightia Excelsa

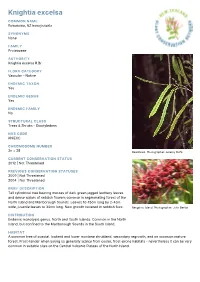

Knightia excelsa COMMON NAME Rewarewa, NZ honeysuckle SYNONYMS None FAMILY Proteaceae AUTHORITY Knightia excelsa R.Br. FLORA CATEGORY Vascular – Native ENDEMIC TAXON Yes ENDEMIC GENUS Yes ENDEMIC FAMILY No STRUCTURAL CLASS Trees & Shrubs - Dicotyledons NVS CODE KNIEXC CHROMOSOME NUMBER 2n = 28 Rewarewa. Photographer: Jeremy Rolfe CURRENT CONSERVATION STATUS 2012 | Not Threatened PREVIOUS CONSERVATION STATUSES 2009 | Not Threatened 2004 | Not Threatened BRIEF DESCRIPTION Tall cylindrical tree bearing masses of dark green jagged leathery leaves and dense spikes of reddish flowers common in regenerating forest of the North Island and Marlborough Sounds. Leaves 10-15cm long by 2-4cm wide, juvenile leaves to 30cm long. New growth covered in reddish fuzz. Rangitoto Island. Photographer: John Barkla DISTRIBUTION Endemic monotypic genus. North and South Islands. Common in the North Island, but confined to the Marlborough Sounds in the South Island. HABITAT A common tree of coastal, lowland and lower montane shrubland, secondary regrowth, and on occasion mature forest. Frost-tender when young so generally scarce from cooler, frost-prone habitats - nevertheless it can be very common in suitable sites on the Central Volcanic Plateau of the North Island. FEATURES Tall tree with columnar (fastigiate) growth-form up to 30 m tall. Trunk up to 1 m diam. Bark dark brown. Branches erect, fastigiate, at first angled, clad in red-brown (rust-coloured), velutinous, tomentum. Juvenile leaves yellow- green, 150-300(-400) x 10-15 mm, narrowly linear-lanceolate, sometimes forked 2,3 or 4 times, margins acutely serrated. Adult leaves dark green, 100-150(-200) x 25-40 mm, broad lanceolate to narrow-oblong or oblong, sometimes obovate, occasionally forked, rigid, bluntly and coarsely serrated, covered in deciduous velutinous red- brown pubescence. -

Department of Conservation Managed Lands

WANGANUI PLANT LIST 195: EGGERS BUSH AND OAPUI SANCTUARY, TARATA ROAD, WAITARA SURVEY DISTRICT Partial plant list for Eggers bush and sketchy plant list for Oapui Sanctuary. Compiled during quick visit on 29 March 2005 by Astrid van Meeuwen−Dijkgraaf, Fiona Wilson and Bryan Williams Updated 1 April 05 Eggers Bush NZMS260 Q19 2632468E − 6229397N (sourced from DOC GIS) Sec 2 Blk XVI Waitara SD, total block 129.5 ha, forested portion ???ha Oapui Sanctuary NZMS260 Q19 2631638E − 6229248N (sourced from DOC GIS) Sec 24 Blk XVI Waitara SD, total block 101.7, forested portion 1.3ha We visited Eggers bush at the invitation of Mr Leon Eggers to assess its biological and possible historic values with a view to apply for funding from the Nature Heritage Fund. The forest has been fenced since (at least 1996), and does not show much impact from stock damage in the past. It has a diverse range of podocarps with the best example of podocarp regeneration I have seen in the Wanganui Conservancy thus far; rimu regeneration especially contains all age/size classes, and regeneration the other podocarps is also prominent. The forest is situated in a meander of the Taramoukou Stream, half a kilometre upstream from the Oapui Sanctuary (which is also in a meander of the same stream). The altitudinal range is from about 100−200m asl. There are about 3 distinct areas of vegetation within this block (also refer to SSBI folder Q19/H060). (1) On the flat river terrace Dacrydium cupressinum (rimu) and Prumnopitys ferruginea (miro) and Dacrycarpus dacrydioides (kahikatea) dominate the 30m canopy.