Don't Network. the Avant Garde After Networks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stop Smiling Magazine :: Interviews and Reviews: Film + Music

Stop Smiling Magazine :: Interviews and Reviews: Film + Music + Books ... http://www.stopsmilingonline.com/story_print.php?id=1097 Downtown Dedication: The Return of Polvo (Touch and Go) Monday, June 23, 2008 By Dan Pearson We could have flown out of Newark, landed in Charlotte, and just hit a barbecue spot in Reidsville, but this was after all the Polvo reunion and it deserved more. We needed to feel as if we were making the descent, notice the disparity in New England and Southern spring, endure interminable DC traffic and feel that we had earned our ribs and slaw. So, I packed the Malibu with I-Roy and U-Roy, stomached $4 gas and my friend Bose and I left from Connecticut in a rainstorm, both of us in fleece. Night one we spent at a Ramada in Fredericksburg, never made it to the battlefield or historic downtown, but instead drove down the divided highway to Allman’s BBQ. I’m wary of food blogs, but the culinary scribes were dead-on: best ribs I have ever had outside Texas, enviable pulled pork and slaw, notable sauce in the squirt bottle — all in an old corner diner with spinning stools. What a foundation, not only for the evening, which consisted of ice cold tap Yuengling and inebriated dancing to Def Leppard in the Ramada lounge, but for the show to come. Just a stateline south, yes, Polvo, the seminal math rock quartet, reunited at their Ground Zero, the Cat’s Cradle in Carrboro. In the morning, it was only better, the slow slalom down Route 40 country roads leaving trails of red clay and another barbecue platter at Short Sugar’s in Danville, Virginia. -

Chart Book Template

Real Chart Page 1 become a problem, since each track can sometimes be released as a separate download. CHART LOG - F However if it is known that a track is being released on 'hard copy' as a AA side, then the tracks will be grouped as one, or as soon as known. Symbol Explanations s j For the above reasons many remixed songs are listed as re-entries, however if the title is Top Ten Hit Number One hit. altered to reflect the remix it will be listed as would a new song by the act. This does not apply ± Indicates that the record probably sold more than 250K. Only used on unsorted charts. to records still in the chart and the sales of the mix would be added to the track in the chart. Unsorted chart hits will have no position, but if they are black in colour than the record made the Real Chart. Green coloured records might not This may push singles back up the chart or keep them around for longer, nevertheless the have made the Real Chart. The same applies to the red coulered hits, these are known to have made the USA charts, so could have been chart is a sales chart and NOT a popularity chart on people’s favourite songs or acts. Due to released in the UK, or imported here. encryption decoding errors some artists/titles may be spelt wrong, I apologise for any inconvenience this may cause. The chart statistics were compiled only from sales of SINGLES each week. Not only that but Date of Entry every single sale no matter where it occurred! Format rules, used by other charts, where unnecessary and therefore ignored, so you will see EP’s that charted and other strange The Charts were produced on a Sunday and the sales were from the previous seven days, with records selling more than other charts. -

Special Issue

ISSUE 750 / 19 OCTOBER 2017 15 TOP 5 MUST-READ ARTICLES record of the week } Post Malone scored Leave A Light On Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 with “sneaky” Tom Walker YouTube scheme. Relentless Records (Fader) out now Tom Walker is enjoying a meteoric rise. His new single Leave } Spotify moves A Light On, released last Friday, is a brilliant emotional piano to formalise pitch led song which builds to a crescendo of skittering drums and process for slots in pitched-up synths. Co-written and produced by Steve Mac 1 as part of the Brit List. Streaming support is big too, with top CONTENTS its Browse section. (Ed Sheeran, Clean Bandit, P!nk, Rita Ora, Liam Payne), we placement on Spotify, Apple and others helping to generate (MusicAlly) love the deliberate sense of space and depth within the mix over 50 million plays across his repertoire so far. Active on which allows Tom’s powerful vocals to resonate with strength. the road, he is currently supporting The Script in the US and P2 Editorial: Paul Scaife, } Universal Music Support for the Glasgow-born, Manchester-raised singer has will embark on an eight date UK headline tour next month RotD at 15 years announces been building all year with TV performances at Glastonbury including a London show at The Garage on 29 November P8 Special feature: ‘accelerator Treehouse on BBC2 and on the Today Show in the US. before hotfooting across Europe with Hurts. With the quality Happy Birthday engagement network’. Recent press includes Sunday Times Culture “Breaking Act”, of this single, Tom’s on the edge of the big time and we’re Record of the Day! (PRNewswire) The Sun (Bizarre), Pigeons & Planes, Clash, Shortlist and certain to see him in the mix for Brits Critics’ Choice for 2018. -

Lush's Final Show @ Manchester Academy

LUSH’S FINAL SHOW @ MANCHESTER ACADEMY larecord.com /photos/2016/11/26/lushs-final-show-manchester-academy November 26th, 2016 | Photos Photos by Todd Nakamine 2016 brought a very successful return for Lush with sold out shows, festival appearances and a new EP Blind Spot. But 2016 also brought the final show the band would play at the Manchester Academy to a somewhat somber crowd. We were soaking in every last note all knowing this was the last show ever (sometimes knowing is worse). Kicking off their high energy set with “De-luxe” and plowing through classic after classic covering their entire career including “Kiss Chase,” “Thoughtforms,” “Etheriel,” “Light From A Dead Star,” “Hypocrite,” “Undertow” plus the new already classic Lush track “Out of Control.” While nothing can replace the late Chris Acland’s subtleties that helped define Lush’s sound, drummer Justin Welsh’s hard and fast style of playing added an extra kick apparent in songs like “Ladykiller,” or as Miki Berenyi said should be renamed “Pussygrabber” in light of U.S.A.’s new president elect, as well as “Sweetness and Light.” Acland’s close friend Michael Conroy of Modern English filled in on bass as Phil King left the band in October. Finishing with the final song of the night “Monochrome,” Emma Anderson, Berenyi and Welsh gave their last waves, left the stage for the final time and the crowd quietly shuffled out having been treated with a very special goodbye. Kicking off the night was Brix & The Extricated featuring post punk legends Brix Smith, Steve Hanley and Paul Hanley (The Fall). -

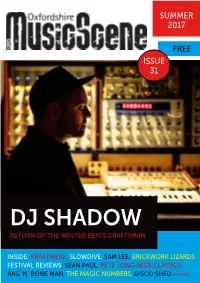

Dj Shadow Return of the Master Beats Craftsman

SUMMER 2017 FREE ISSUE 31 DJ SHADOW RETURN OF THE MASTER BEATS CRAFTSMAN INSIDE: KRAFTWERK, SLOWDIVE, SAM LEE, BRICKWORK LIZARDS FESTIVAL REVIEWS: SEAN PAUL, PETE TONG IBIZA CLASSICS, RAG ‘N’ BONE MAN, THE MAGIC NUMBERS, DISCO SHED & MORE OMS31 MUSIC NEWS There’s a history of multi – venue metro festivals in Cowley Road with Truck’s OX4 and then Gathering setting the pace. Well now Future Perfect have taken up the baton with Ritual Union on Saturday October 21. Venues are the O2 Academy 1 and 2, The Library, The Bullingdon and Truck Store. The first stage of acts announced includes Peace, Toy, Pinkshinyultrablast, Flamingods, Low Island, Dead Reborn local heroes Ride are sounding in fine stage Pretties, Her’s, August List and Candy Says with DJ fettle judging by their appearance at the 6 Music sets from the Drowned in Sound team. Tickets are Festival in Glasgow. The former Creation shoegaze £25 in advance. trailblazers play the New Theatre, Oxford on July 10, having already appeared at Glastonbury, their The Jericho Tavern in Walton Street have a new first local show in many years. They have also promoter to run their upstairs gigs. Heavy Pop announced a major UK tour. The eagerly awaited are well – known in Reading having run the Are new album, the Erol Alkan produced Weather Diaries You Listening? festival there for 5 years. Already is just released. (See our album review in the Local confirmed are an appearance from Tom Williams Releases section). Tickets for New Theatre gig with (formerly of The Boat) on September 16 and Original Spectres supporting, can be bought from Rabbit Foot Spasm Band on October 13 with atgtickets.com Peerless Pirates and Other Dramas. -

NEW RELEASE Cds 24/5/19

NEW RELEASE CDs 24/5/19 BLACK MOUNTAIN Destroyer [Jagjaguwar] £9.99 CATE LE BON Reward [Mexican Summer] £9.99 EARTH Full Upon Her Burning Lips £10.99 FLYING LOTUS Flamagra [Warp] £9.99 HAYDEN THORPE (ex-Wild Beasts) Diviner [Domino] £9.99 HONEYBLOOD In Plain Sight [Marathon] £9.99 MAVIS STAPLES We Get By [ANTI-] £10.99 PRIMAL SCREAM Maximum Rock 'N' Roll: The Singles [2CD] £12.99 SEBADOH Act Surprised £10.99 THE WATERBOYS Where The Action Is [Cooking Vinyl] £9.99 THE WATERBOYS Where The Action Is [Deluxe 2CD w/ Alternative Mixes on Cooking Vinyl] £12.99 AKA TRIO (Feat. Seckou Keita!) Joy £9.99 AMYL & THE SNIFFERS Amyl & The Sniffers [Rough Trade] £9.99 ANDREYA TRIANA Life In Colour £9.99 DADDY LONG LEGS Lowdown Ways [Yep Roc] £9.99 FIRE! ORCHESTRA Arrival £11.99 FLESHGOD APOCALYPSE Veleno [Ltd. CD + Blu-Ray on Nuclear Blast] £14.99 FU MANCHU Godzilla's / Eatin' Dust +4 £11.99 GIA MARGARET There's Always Glimmer £9.99 JOAN AS POLICE WOMAN Joanthology [3CD on PIAS] £11.99 JUSTIN TOWNES EARLE The Saint Of Lost Causes [New West] £9.99 LEE MOSES How Much Longer Must I Wait? Singles & Rarities 1965-1972 [Future Days] £14.99 MALCOLM MIDDLETON (ex-Arab Strap) Bananas [Triassic Tusk] £9.99 PETROL GIRLS Cut & Stitch [Hassle] £9.99 STRAY CATS 40 [Deluxe CD w/ Bonus Tracks + More on Mascot]£14.99 STRAY CATS 40 [Mascot] £11.99 THE DAMNED THINGS High Crimes [Nuclear Blast] FEAT MEMBERS OF ANTHRAX, FALL OUT BOY, ALKALINE TRIO & EVERY TIME I DIE! £10.99 THE GET UP KIDS Problems [Big Scary Monsters] £9.99 THE MYSTERY LIGHTS Too Much Tension! [Wick] £10.99 COMPILATIONS VARIOUS ARTISTS Lux And Ivys Good For Nothin' Tunes [2CD] £11.99 VARIOUS ARTISTS Max's Skansas City £9.99 VARIOUS ARTISTS Par Les Damné.E.S De La Terre (By The Wretched Of The Earth) £13.99 VARIOUS ARTISTS The Hip Walk - Jazz Undercurrents In 60s New York [BGP] £10.99 VARIOUS ARTISTS The World Needs Changing: Street Funk.. -

AND. MTIONAL Lmj)Ef JOURNAL

¦ "' ¦ ¦ ¦ ¦ s ' ¦ - - "" -' - - " . '.-' ; .r *"-. -' -' ¦ '--. - -- ..- ¦.- .. ...,.:_.. .. ' '" ' •- - ' ' — - * ' <.' >-j- -i- .i- .; . v; f i. tr _ il. i. 3Enmwnc«> MURDER. AND SUICIDE IN -jFomstf DREADFUL " ' finsburt. ,•;: FRANCE, Shortly after the opening of the Worship-street Friday morning, -an official communi- IfaBKBr^rUpon Friday, JL Gustavo de police-court on "rrr m cation was made to Mr. Bingham, the sitting magis- 1 ^nnnt's amendment although, compared with division, ol a ^ttounwu^ de Garni) of ^e most miik-aaci.Tratcr trate, bv Inspector Jervis, of the G which had been enacted in the J *Jl was rejected without even the ceremony frio-htfuf tragedv e e ter the court, ill the course oi tho pre- f T Sl-the <ihambiu'thusraiafyin*ithe act4)fthe neighbourhood of nHit, The inspector stated that about ten ¦P day. On Saturday the anti-indenmity cedin"- rions clock that morning information arrived at the po- Richard amendment was discussed and rejected. pi^ifii- o' was on - lice station in Featherstone-street, where he address was passed. The numbers Mondav the h Barry, surgical m- **' , 216 ; against, H^ duty, that a man, named Josep a- ftr {he address 33; majority, Mm 6 No. 4 . greater part of the left abstained fr om AND. strument iiialcer, residing at Lukof^, * ?*£ The . MTIONAL lMj)Ef iiight, murdered JOURNAL. duringthe precedmg ¦ Finsburv, had, »ti)tii>S- . T his wife, Marv Priscilla Barry, and afterwards de- ViV&sBSiAtios ov ihe Address.—LotJisPja-ruppE s • ' his throat with a razor. WrarasDiTNight TOL. VIIL NO. 377. - - ¦ stroved lihnsolf-. bv cutting «4it:--*--Pabis was of 2H, Tex O'CMGK.of — LOl^fc S^^ immediately proceeded to tne ya meeting' held Deputies ^JSZ^S^S^ He (thc inspector) i^da the ^ house, and, from inquiries, ascertained the following servative party, to express their confidence in, and crowds :—It appeared Lim of the people assembled in the public , g particulars of this dreadful occurrence „TT their determination to support the present plaees. -

CD List, No Songs

CD list Brian Auger 51 Sacred Fire Santana 2 Skull & Roses Grateful Dead 52 Borboletta Santana 3 100 Year Hall - Disc 1 Grateful Dead 53 Santana (galaxy) Santana 4 Europe 72 - Disc 1 Grateful Dead 54 Supernatural Santana 5 Europe 72 - Disc 2 Grateful Dead 55 Shaman Santana 6 Steal Your Face - Disc 1 Grateful Dead 56 Time out of Mind Bob Dylan 7 Steal Your Face - Disc 2 Grateful Dead 57 Love and Theft Bob Dylan 8 Without a Net - Disc 1 Grateful Dead 58 Highway 61 Revisited Bob Dylan 9 Without a Net - Disc 2 Grateful Dead 59 Blonde on Blonde Bob Dylan 10 One from the Vault (composite CD) Grateful Dead 60 The Ultimate Experience Jimi Hendrix 11 Two from the Vault - Disc 1 Grateful Dead 61 Jefferson Airplane Loves You - Jefferson Airplane Disc 1 12 Two from the Vault - Disc 2 Grateful Dead 62 Jefferson Airplane Loves You - Jefferson Airplane 13 Fallout from the Phil Zone - Disc 1 Grateful Dead Disc 2 14 Fallout from the Phil Zone - Disc 2 Grateful Dead 63 Jefferson Airplane Loves You - Jefferson Airplane 15 Reckoning Grateful Dead Disc 3 16 Workingman's Dead Grateful Dead 64 Blows against the Empire Jefferson Airplane 17 American Beauty Grateful Dead 65 Red Octopus Jefferson Airplane 18 Wake of the Flood Grateful Dead 66 America's Choice Hot Tuna 19 Terrapin Station - Studio Grateful Dead 67 Phosphorescent Rat Hot Tuna 20 Built to Last Grateful Dead 69 Greatest Hits Three Dog Night 21 So Many Roads - disc 1 Grateful Dead 70 Waiting for the Sun Doors, The 22 So Many Roads - disc 2 Grateful Dead 71 Best of the Doors Doors, The 23 So Many Roads - disc 3 Grateful Dead 72 Essential Rarities Doors, The 24 Steppin' Out (England '72) - cd 1 Grateful Dead 73 Time Traveller - Disc 1 Moody Blues 25 Steppin' Out (England '72) - cd 2 Grateful Dead 74 Time Traveller - Disc 2 Moody Blues 26 Steppin' Out (England '72) - cd 3 Grateful Dead 76 Rubber Soul/Sgt. -

Broadcast Bulletin Issue Number 219 03/12/12

Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin Issue number 219 3 December 2012 1 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 219 3 December 2012 Contents Introduction 3 Notice of Sanction Sister Ruby Ramadan Special Radio Asian Fever (Leeds), 17 August 2011, 12:00 and 18 August 2011, 11:00 4 Standards cases In Breach Asian Sound Radio Asian Sound Radio, 9 April 2012, 11:30 to 12:30 6 American Dad FX, 11 August 2012, 20:30 14 GirlGirl ChatGirl TV (Sky Channel 937), 22 August 2012, 07:30 to 08:30 18 Big Wednesday with Shawn Phonic FM, 12 September 2012, 11:40 22 Borkotmoy Sehri NTV, 30 July 2012, 02:00 25 Advertising scheduling cases In Breach Advertising minutage and advertising break patterns Sahara One, 16 July 2012 to 31 July 2012, various times 28 Advertising minutage Vox Africa, 1 June 2012 to 5 July 2012, various times 30 Other Programmes Not in Breach 32 Complaints Assessed, Not Investigated 33 Investigations List 42 2 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 219 3 December 2012 Introduction Under the Communications Act 2003, Ofcom has a duty to set standards for broadcast content as appear to it best calculated to secure the standards objectives1, Ofcom must include these standards in a code or codes. These are listed below. The Broadcast Bulletin reports on the outcome of investigations into alleged breaches of those Ofcom codes, as well as licence conditions with which broadcasters regulated by Ofcom are required to comply. These include: a) Ofcom’s Broadcasting Code (“the Code”), which, can be found at: http://stakeholders.ofcom.org.uk/broadcasting/broadcast-codes/broadcast-code/. -

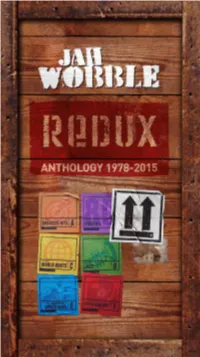

View the Redux Book Here

1 Photo: Alex Hurst REDUX This Redux box set is on the 30 Hertz Records label, which I started in 1997. Many of the tracks on this box set originated on 30 Hertz. I did have a label in the early eighties called Lago, on which I released some of my first solo records. These were re-released on 30 Hertz Records in the early noughties. 30 Hertz Records was formed in order to give me a refuge away from the vagaries of corporate record companies. It was one of the wisest things I have ever done. It meant that, within reason, I could commission myself to make whatever sort of record took my fancy. For a prolific artist such as myself, it was a perfect situation. No major record company would have allowed me to have released as many albums as I have. At the time I formed the label, it was still a very rigid business; you released one album every few years and ‘toured it’ in the hope that it became a blockbuster. On the other hand, my attitude was more similar to most painters or other visual artists. I always have one or two records on the go in the same way they always have one or two paintings in progress. My feeling has always been to let the music come, document it by releasing it then let the world catch up in its own time. Hopefully, my new partnership with Cherry Red means that Redux signifies a new beginning as well as documenting the past. -

Religion and the Occupy Movements of 2011

This is an Open Access document downloaded from ORCA, Cardiff University's institutional repository: http://orca.cf.ac.uk/85068/ This is the author’s version of a work that was submitted to / accepted for publication. Citation for final published version: Cloke, Paul, Sutherland, Callum and Williams, Andrew 2016. Postsecularity, political resistance, and protest in the Occupy Movement. Antipode 48 (3) , pp. 497-523. 10.1111/anti.12200 file Publishers page: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/anti.12200 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/anti.12200> Please note: Changes made as a result of publishing processes such as copy-editing, formatting and page numbers may not be reflected in this version. For the definitive version of this publication, please refer to the published source. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite this paper. This version is being made available in accordance with publisher policies. See http://orca.cf.ac.uk/policies.html for usage policies. Copyright and moral rights for publications made available in ORCA are retained by the copyright holders. Postsecularity, Political Resistance, and Protest in the Occupy Movement POST-PRINT VERSION Paul Cloke, Callum Sutherland (University of Exeter) and Andrew Williams (Cardiff University) Published online in Antipode 22 October 2015 Cloke, P., Sutherland, C. and Williams, A. 2015. Postsecularity, political resistance, and protest in the Occupy Movement. Antipode (10.1111/anti.12200) 1 Abstract This paper examines and critically interprets the interrelations between religion and the Occupy movements of 2011. It presents three main arguments. First, through an examination of the Occupy Movement in the UK and USA—and in particular of the two most prominent Occupy camps (Wall Street and London Stock Exchange)—the paper traces the emergence of postsecularity evidenced in the rapprochement of religious and secular actors, discourses, and practices in the event-spaces of Occupy. -

Every Purchase Includes a Free Hot Drink out of Stock, but Can Re-Order New Arrival / Re-Stock

every purchase includes a free hot drink out of stock, but can re-order new arrival / re-stock VINYL PRICE 1975 - 1975 £ 22.00 30 Seconds to Mars - America £ 15.00 ABBA - Gold (2 LP) £ 23.00 ABBA - Live At Wembley Arena (3 LP) £ 38.00 Abbey Road (50th Anniversary) £ 27.00 AC/DC - Live '92 (2 LP) £ 25.00 AC/DC - Live At Old Waldorf In San Francisco September 3 1977 (Red Vinyl) £ 17.00 AC/DC - Live In Cleveland August 22 1977 (Orange Vinyl) £ 20.00 AC/DC- The Many Faces Of (2 LP) £ 20.00 Adele - 21 £ 19.00 Aerosmith- Done With Mirrors £ 25.00 Air- Moon Safari £ 26.00 Al Green - Let's Stay Together £ 20.00 Alanis Morissette - Jagged Little Pill £ 17.00 Alice Cooper - The Many Faces Of Alice Cooper (Opaque Splatter Marble Vinyl) (2 LP) £ 21.00 Alice in Chains - Live at the Palladium, Hollywood £ 17.00 ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - Enlightened Rogues £ 16.00 ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - Win Lose Or Draw £ 16.00 Altered Images- Greatest Hits £ 20.00 Amy Winehouse - Back to Black £ 20.00 Andrew W.K. - You're Not Alone (2 LP) £ 20.00 ANTAL DORATI - LONDON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA - Stravinsky-The Firebird £ 18.00 Antonio Carlos Jobim - Wave (LP + CD) £ 21.00 Arcade Fire - Everything Now (Danish) £ 18.00 Arcade Fire - Funeral £ 20.00 ARCADE FIRE - Neon Bible £ 23.00 Arctic Monkeys - AM £ 24.00 Arctic Monkeys - Tranquility Base Hotel + Casino £ 23.00 Aretha Franklin - The Electrifying £ 10.00 Aretha Franklin - The Tender £ 15.00 Asher Roth- Asleep In The Bread Aisle - Translucent Gold Vinyl £ 17.00 B.B.