And Turner V Jacob (2006)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advanced Equity and Trusts

ADVANCED EQUITY AND TRUSTS University of London LLM The course is led by: Professor Alastair Hudson Professor of Equity & Law Department of Law, Queen Mary, University of London 2006/2007 1 www.alastairhudson.com | © professor alastair hudson Advanced Equity and Trusts Law Introduction This course intends to focus on aspects of equity and trusts in two specific contexts: commerce and the home. It will advance novel conceptual approaches to two significant arenas in which equitable doctrines like the trust are deployed. In the context of commercial activity the course will consider the manner in which discretionary equitable doctrines are avoided but also the significant role which the law of trusts plays nevertheless in commercial and financial activity. In the context of the home to consider the various legal norms which coalesce in the treatment of the home: whether in equitable estoppel, trusts implied by law, family law, human rights law and housing law. Teaching Organised over three terms, 2 hours per week, comprising a lecture in the first week followed, generally, by a seminar in the following week as a cycle. See, however, the three introductory topics which are dealt with differently. Examination / assessment Examination will be by one open-book examination which will ask students to attempt three questions in three hours. Textbooks It is suggested that you acquire a textbook and you may find it useful to acquire a cases and materials book, particularly if you have not studied English law before. Recommended general text:- *Alastair Hudson: Equity and Trusts (4th ed.: Cavendish Publishing 2005). Other textbooks:- Hanbury and Martin: Modern Equity (17th ed., by Dr J. -

The Trust up and Running

10 The trust up and running SUMMARY The duty of investment The Trustee Act 2000 The standard of prudence in making trust investments ‘Social’ or ‘ethical’ investing The delegation of trustee functions The power of maintenance The power of advancement Appointment, retirement, and removal of trustees Custodian, nominee, managing, and judicial trustees Bene" ciaries’ rights to information Variation of trusts 10.1 Trustees, as legal owners of the trust property, have all the rights and powers to deal with the trust property as would any other legal owner, although they must, of course, exercise these rights and powers solely in the interest of the benefi ciaries. Because they are trustees, however, they have further particular powers and duties arising from their offi ce, traditionally the most important of which are the duty of investment and the powers of maintenance and advancement. 110-Penner-Chap10.indd0-Penner-Chap10.indd 227272 55/29/2008/29/2008 111:03:521:03:52 PPMM The duty of investment | 273 e duty of investment 10.2 e duty of investment has two main aspects: (1) a duty to invest the trust property so as to be ‘even-handed’ between the diff erent classes of benefi ciary; and (2) a duty to invest so that the fund is preserved from risk yet a reasonable return on capital is made. Even-handedness between the benefi ciaries 10.3 In many trusts the benefi t of the property is divided between income and capi- tal benefi ciaries (3.19). In legal terms, income is whatever property actually arises as a separate payment as a result of holding the capital property. -

Tracing Is a Process Not a Remedy

Tracing - Scenario 1(b): Trustee Mixes Trust Money - Tracing is a process not a remedy. With His Own In His Account, subsequently - It allows us to identify a new asset as the purchases property with some money in the substitute for the old (Foskett v McKeown). account, then exhausts remaining money. - Tracing follows the value of the beneficiaries - SOLUTION: Re Oatway: We get an property, not the property itself (following). exception to the rule in Hallett’s estate: if the wrongdoer purchased assets which still exist, Distinguishing Tracing; Following & Claiming then it is presumed that he did so with the - Following is the process of following the same stolen money and the beneficiaries are asset as it moves from hand to hand. entitled to the assets. - Claiming refers to the process of recovering property, or the substitute for that property (This - Scenario 1(c): Trustee Mixes Money With His refers to the Barnes v Addy; knowing receipt, Own In His Account, and makes payment in knowing assistance doctrine - MUST and out of that account. CONSIDER THIS AFTER TRACING). - SOLUTION: Lofts v McDonald: Lowest Intermediate Balance Rule: trust cannot claim more than the lowest intermediate balance Tracing at Common Law - credited to the wrongdoer’s bank account Tracing is not unique to equity, however at CL it - If it went up from the lowest point, that is requires that the property you are tracing is not the trust’s money. identifiable, giving rise to problems with banks. - - Although you are deprived of a proprietary Equity has developed rules for identifying remedy, not personal remedies. -

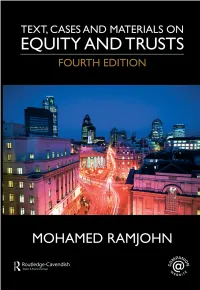

Text, Cases and Materials on Equity and Trusts

TEXT, CASES AND MATERIALS ON EQUITY AND TRUSTS Fourth Edition Text, Cases and Materials on Equity and Trusts has been considerably revised to broaden the focus of the text in line with most LLB core courses to encompass equity, remedies and injunctions and to take account of recent major statutory and case law developments. The new edition features increased pedagogical support to outline key points and principles and improve navigation; ‘notes’ to encourage students to reflect on areas of complexity or controversy; and self-test questions to consolidate learning at the end of each chapter. New to this edition: • Detailed examination of The Civil Partnership Act 2004 and the Charities Act 2006. • Important case law developments such as Stack v Dowden (constructive trusts and family assets), Oxley v Hiscock (quantification of family assets), Barlow Clowes v Eurotrust (review of the test for dishonesty), Abou-Ramah v Abacha (dishonest assistance and change of position defence), AG for Zambia v Meer Care & Desai (review of the test for dishonesty), Re Horley Town Football Club (gifts to unincorporated association), Re Loftus (defences of limitation, estoppel and laches), Templeton Insurance v Penningtons Solicitors (Quistclose trust and damages), Sempra Metals Ltd v HM Comm of Inland Revenue (compound interest on restitution claims) and many more. • New chapters on the equitable remedies of specific performance, injunctions, rectification, rescission and account. • Now incorporates extracts from the Law Commission’s Reports and consultation papers on ‘Sharing Homes’ and ‘Trustee Exemption Clauses’ as well as key academic literature and debates. The structure and style of previous editions have been retained, with an emphasis on introduc- tory text and case extracts of sufficient length to allow students to develop analytical and critical skills in reading legal judgments. -

Creation of Express Trusts Capacity

Creation of Express Trusts Capacity - ‘Legal competency or qualification’ - Two common exclusions = poor mental health, infancy - S1(6) LPA 1925: a minor cannot hold a legal estate in land (so cannot create a trust of land). THE THREE CERTAINTIES - Knight v Knight: Lord Langdale: for an express trust to be created the settlor must express 3 things with certainty. o Certainty of intention o Certainty of subject matter o Certainty of objects Certainty of Intention - Did settlor intend to subject the property to a trust obligation? - Two ways in which a trust can be created: o The settlor declares himself trustee of property that he already owns; o Settlor transfers property to another person directing that they hold it on trust for the beneficiary. - Has the settlor done enough to make clear his intention? - Re Kayford Ltd – Megarry LJ: ‘a trust can be created without using the words “trust” or “confidence” or the like; the question is whether in substance a sufficient intention to create a trust has been manifested’. - Company opened separate account, ‘Customer’s Trust deposit Account’ to pay in money received for goods not yet delivered, withdrawing the money only if goods were later delivered – so they could refund customers if goods not supplied (if company went into liquidation). - Held: trust had been created. - Paul v Constance: C separate from his wife + lived with P. A number of times C told P that the money was as much hers as his. o C died intestate + as he had not divorced his wife, wife was entitled to all of his estate. -

Claims Against Third-Party Recipients of Trust Property

Cambridge Law Journal, 76(2), July 2017, pp. 399–429 © Cambridge Law Journal and Contributors 2017. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike licence (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the same Creative Commons licence is included and the original work is properly cited. The written permission of Cambridge University Press must be obtained for commercial re-use. doi:10.1017/S0008197317000423 CLAIMS AGAINST THIRD-PARTY RECIPIENTS OF TRUST PROPERTY DAVID SALMONS* ABSTRACT. This article argues that claims to recover trust property from third parties arise in response to a trustee’s duty to preserve identifiable property, and that unjust enrichment is incompatible with such claims. First, unjust enrichment can only assist with the recovery of abstract wealth and so it does not assist in the recovery of specific property. Second, it is difficult to identify a convincing justification for introducing unjust enrich- ment. Third, it will work to the detriment of innocent recipients. The article goes on to show how Re Diplock supports this analysis, by demonstrating that no duty of preservation had been breached and that a proprietary claim should not have been available in that case. The simple conclusion is that claims to recover specific property and claims for unjust enrichment should be seen as mutually exclusive. KEYWORDS: trusts, third parties, proprietary claims, knowing receipt, res- titution, unjust enrichment, Re Diplock. I. INTRODUCTION According to orthodox trust principles, where property is transferred in breach of trust, a beneficiary can either bring a proprietary claim to recover the property or a personal claim against a knowing recipient of the trust property (hereinafter, the combination of these two claims will be referred to as the “equitable regime”). -

Landmark Cases in Tracing – a Pitch

Landmark Cases in Tracing – A Pitch Landmark Cases in Tracing A pitch for an edited collection of in-depth case analyses Dr Derek Whayman, Newcastle University. [email protected] Prof Katy Barnett, University of Melbourne. [email protected] Theme and Justification Tracing is a process and claim used for recovering misappropriated property, mainly that originally held on trust or by a corporation. It allows claimants to recover not only the original misappropriated property, but also its substitute – what the property was exchanged for in a subsequent transaction. Since this claim is a right of property, it brings the claimant the advantage of priority over other creditors in insolvency and access to any increase in value, either in the property itself or from the substitute. If the property is passed to or from another person or, say, a shell company, the right to claim follows that property and is not left on the person. From this, it is no wonder it is popular with claimants. However, tracing is still under-researched and under-theorised. There is little agreement as to how this claim can be justified theoretically, what its limits are and how they vary in accordance with the multitude of different facts the courts have seen and will see in the future. Academics and judges are still feeling their way around its fundamental questions. Yet not only are the answers to these theoretical questions controverted, they go to the heart of what every litigant wants to know: what may or may not be claimed? These questions are of fundamental importance on a practical basis too. -

Intermediated Securities: Who Owns Your Shares? a Scoping Paper

6~~mission Reforming the law Intermediated securities: who owns your shares? A Scoping Paper 11 November 2020 © Crown copyright 2020 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.lawcom.gov.uk. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to [email protected]. The Law Commission The Law Commission was set up by the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. The Law Commissioners are: The Right Honourable Lord Justice Green, Chairman Professor Sarah Green Professor Nicholas Hopkins Professor Penney Lewis Nicholas Paines QC The Chief Executive of the Law Commission is Phil Golding. The Law Commission is located at 1st Floor, Tower, 52 Queen Anne's Gate, London SW1H 9AG. The terms of this scoping paper were agreed on 30 September 2020. The text of this scoping paper is available on the Law Commission's website at http://www.lawcom.gov.uk. i Contents Page GLOSSARY VII LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS XIV REFERENCES TO LAW COMMISSION PUBLICATIONS XVI CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 Background to this paper 1 Terms of reference and consultation 3 Intermediated securities: at a glance 4 The Law Commission’s view on intermediation 8 A range of possible solutions 8 Costs and benefits -

Claims Against Third-Party Recipients of Trust Property

Cambridge Law Journal, 76(2), July 2017, pp. 399–429 © Cambridge Law Journal and Contributors 2017. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike licence (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the same Creative Commons licence is included and the original work is properly cited. The written permission of Cambridge University Press must be obtained for commercial re-use. doi:10.1017/S0008197317000423 CLAIMS AGAINST THIRD-PARTY RECIPIENTS OF TRUST PROPERTY DAVID SALMONS* ABSTRACT. This article argues that claims to recover trust property from third parties arise in response to a trustee’s duty to preserve identifiable property, and that unjust enrichment is incompatible with such claims. First, unjust enrichment can only assist with the recovery of abstract wealth and so it does not assist in the recovery of specific property. Second, it is difficult to identify a convincing justification for introducing unjust enrich- ment. Third, it will work to the detriment of innocent recipients. The article goes on to show how Re Diplock supports this analysis, by demonstrating that no duty of preservation had been breached and that a proprietary claim should not have been available in that case. The simple conclusion is that claims to recover specific property and claims for unjust enrichment should be seen as mutually exclusive. KEYWORDS: trusts, third parties, proprietary claims, knowing receipt, res- titution, unjust enrichment, Re Diplock. I. INTRODUCTION According to orthodox trust principles, where property is transferred in breach of trust, a beneficiary can either bring a proprietary claim to recover the property or a personal claim against a knowing recipient of the trust property (hereinafter, the combination of these two claims will be referred to as the “equitable regime”). -

Remodelling Knowing Receipt As a Gains-Based Wrong

Whayman D. Remodelling Knowing Receipt as a Gains-Based Wrong. Journal of Business Law 2016, 7, 565-588. Copyright: This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced version of an article accepted for publication in Journal of Business Law following peer review. The definitive published version is available online on Westlaw UK or from Thomson Reuters DocDel service. Date deposited: 12/09/2016 Embargo release date: 01 September 2017 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License Newcastle University ePrints - eprint.ncl.ac.uk Remodelling Knowing Receipt as a Gains-Based Wrong Derek Whayman* [email protected] Newcastle Law School Newcastle University 21–24 Windsor Terrace Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 7RU Abstract This article analyses the nature of knowing receipt. It finds its previous characterisations as a form of unjust enrichment or trustee-like liability wanting in the face of newer authority and complex commercial situations. It argues that knowing receipt is a gains-based profit- disgorging wrong and this best describes its remedies. 1. Introduction The action in knowing receipt is an invaluable tool in the armoury of the claimant who wants to recover misapplied trust or company property from a stranger to the trust or fiduciary relation. It might be that the trustee or fiduciary is a man of straw or has disappeared or simply that the recipient is easier to sue. Then, provided the claimant can show that the recipient beneficially received property traceable to a breach of trust of fiduciary duty with cognisance of that breach, a personal claim exists.1 However, the precise nature of knowing receipt and particularly how this translates into the remedy available – namely quantum – is contested. -

6FFLK003: Law of Trusts | King's College London

09/25/21 6FFLK003: Law of Trusts | King's College London 6FFLK003: Law of Trusts View Online 1. Mitchell, C., Hayton, D. J., Hayton, D. J., Marshall, O. R. & Marshall, O. R. Hayton and Mitchell commentary and cases on the law of trusts and equitable remedies. (Sweet & Maxwell, 2010). 2. Penner, J. E. The law of trusts. vol. Core text series (Oxford University Press, 2014). 3. Penner, J. E. The law of trusts. vol. Core text series (Oxford University Press, 2012). 4. Mitchell, C., Hayton, D. J., Hayton, D. J., Marshall, O. R. & Marshall, O. R. Hayton and Mitchell commentary and cases on the law of trusts and equitable remedies. (Sweet & Maxwell, 2010). 5. Senior Courts Act 1981. 6. Judicature Acts 1873-1875. 1/36 09/25/21 6FFLK003: Law of Trusts | King's College London 7. Mason, Anthony. Equity’s Role in the Twentieth Century. King’s College Law Journal 8, (1997). 8. Mitchell, C., Hayton, D. J., Hayton, D. J., Marshall, O. R. & Marshall, O. R. Hayton and Mitchell commentary and cases on the law of trusts and equitable remedies. (Sweet & Maxwell, 2010). 9. Andrew Burrows. We Do This at Common Law but That in Equity. Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 22, 1–16 (2002). 10. Smith, L. Fusion and Tradition. in Equity in commercial law (Lawbook Co, 2005). 11. Penner, J. E. The law of trusts. vol. Core text series (Oxford University Press, 2012). 12. Mitchell, C., Hayton, D. J., Hayton, D. J., Marshall, O. R. & Marshall, O. R. Hayton and Mitchell commentary and cases on the law of trusts and equitable remedies. -

'Prudence' Test for Trustees in Pension

The ‘Prudence’ Test for Trustees in Pension Scheme Investment: Just a Shorthand for ‘Take Care’ David Pollard* ‘Investment powers are an example of equitable principles being supplemented by high-level statutory statements of principle which make the law, if anything, more flexible than it was before. I do not think that we need fear such reformulations. After all most of the general statements of equitable principles which we use today are simply a way of putting the matter which occurred to some Victorian judge in the course of an ex tempore judgment which his successors sought sufficiently felicitous to be worth repeating. There is nothing sacred about such formulations and I do not see why Victorian judges should be regarded as having had some special insight into the mot juste which the Australian Parliament or Professor Goode’s committee or even modern judges lack. What matters is not the source of the principle but whether the judges are willing to regard it as a principle rather than try to interpret it as a black–letter rule.’ Lord Hoffmann (then Hoffmann LJ) in his 1994 paper ‘Equity and its role for superannuation pension schemes in the 1990s’1 This article looks at the duty of care for trustees of an occupational pension scheme in relation to in investment. It is common to refer to a duty of ‘prudence’ or to be ‘prudent’ or to be a ‘prudent person’. This article looks at the meaning of prudence in this context and whether it helps in defining the trustee’s duty of care in relation to investments.