Knowing Receipt and the Law of Restitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

III. KNOWING Assistance .. ·I·

WHEN IS A STRANGERA CONSTRUCTIVETRUSTEE? 453 WHEN IS A STRANGER A CONSTRUCTIVE TRUSTEE? A CRITIQUE OF RECENT DECISIONS SUSAN BARKEHALL THOMAS• 1his articleexplores the conceptualdevelopment of Cet article explore le developpementconceptuel de third party liabilityfor participation in a breach of responsabilite civile dans la participation a fiduciary duty. 1he authorprovides a criticalanalysis l'inexecution d'une obligationfiduciaire. L 'auteur of thefoundations of third party liability in Canada fournit une analyse critique des fondations de la and chronicles the evolution of context-specific responsabilitecivile au Canada et decrit /'evolution liability tests. In particular, the testsfor the liability d'essais de responsabilites particulieres a une of banks and directorsare developed in their specific situation.Les essais de responsabilitedes banques el contexts. 1he author then provides a reasoned des adminislrateurssont particulierementdeveloppes critique of the Supreme Court of Canada's recent dans leur contexte precis. L 'auteurfournit ensulte trend towards context-independenttests. 1he author une critique raisonnee de la recente tendance de la concludes by arguing that the current approach is Cour supreme du Canada pour /es essais inadequateand results in an incoherentframework independantset particuliersa une situation.L 'auteur for the law of third party liability in Canada. conclut en pretendant que la demarche actuelle est inadequateet entraine un cadre incoherentpour la loi sur la responsabilitecivile au Canada. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. IN1R0DUCTION . • • • • . • . • . 453 II. KNOWING PARTICIPATION ......••...........•....•..... 457 A. BANKCASES . 457 B. APPLICATIONOF TIIE "PuT ON INQUIRY" TEST .....•...... 459 C. CONCEPTUALPROBLEMS Wl11I THE "PuT ON INQUIRY" TEST • . • . • • • . • . • . • . 463 D. CONCLUSIONSFROM PART II . 467 III. KNOWING AsSISTANCE .. ·I·............................ 467 A. THEAIR CANADA DECISION . • • • . • . 468 IV. -

Summary Record of the 47Th Meeting

Document:- A/CN.4/SR.47 Summary record of the 47th meeting Topic: Formulation of the Nürnberg Principles Extract from the Yearbook of the International Law Commission:- 1950 , vol. I Downloaded from the web site of the International Law Commission (http://www.un.org/law/ilc/index.htm) Copyright © United Nations 44 47th meeting — 15 June 1950 Code of Offences against the Peace and Security of sion must now decide whether or not it wished to adopt Mankind. the principles that an order given by a superior made 132. Mr. BRIERLY did not think that that was the the subordinate responsible; that was the first question problem. In no country did the law recognize superior it would have to decide. orders as a defence when a crime had been committed. 139. The CHAIRMAN again requested the Commis- sion to consider the matter and to form an opinion so 133. Mr. el-KHOURY expained that under the law that it could adopt a definite position with regard to the of his country, which was based on Islamic law, an decisions it was about to take. order given by a superior did not in itself free from responsibility the person to whom the order was given. The meeting rose at 1 p.m. The order of a chief who had power to enforce the execution of his order might remove that responsibility. He observed that the text of Principle IV, which was based on the text of article 8 of the Charter of the Niirnberg Tribunal, had been established by the Com- 47th MEETING mission the previous year. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-316-62194-3 — Equity and Trusts in Australia Michael Bryan , Vicki Vann , Susan Barkehall Thomas Index More Information INDEX

Cambridge University Press 978-1-316-62194-3 — Equity and Trusts in Australia Michael Bryan , Vicki Vann , Susan Barkehall Thomas Index More Information INDEX accounts of profits, 54–5, 169 limitation statutes, 84–5 remedies for. See remedies allowances, 57–8 unclean hands, 86–8, 168 for breach of trust breach of confidence, 197 beneficiaries, 206 ‘but for’ test, 65–6, 333 calculation of, 55–7 administration of trust and, acquiescence, 85–6 207 calculation of equitable as equitable defence to creditors’ rights and, 313–14 compensation, 60–1 breach of trust, 329–30 differences between fixed breach of fiduciary duty, overlap with laches, 85–6 and discretionary trusts 63–5 advancement for, 207 breach of trust, 61–3 presumption of, 357–9 ‘gift-over’ right, 208–9 calculation of equitable agency indemnification of trustees, damages trusts and, 210–11 311–13 causation standard, 65–6 aggravated damages, 68 interest, trustees’ right to common law adjustments to Anton Piller order, 39 impound, 314 quantum, 66–8 Aristotle, 4 investment of trust funds, categories of constructive trusts, assessment of equitable 297, 299 371 damages, 51 ‘list certainty’, 227 as remedy to proprietary in addition to injunction or sui juris, 278, 312 estoppel, 380–2 specific performance, 51 trust property and, 208 as restitutionary remedy in substitution for injunction trustees’ right to recover for unjust enrichment, or specific performance, overpayment from, 315 380–2 51–2 breach of confidence, 17–18, 47, Baumgartner constructive assignments 50, 68 trusts, 375–9 equitable property, 138–9 defences to. See defences to common intention, family future property, 137–8 breach of confidence property disputes and, gifts, 133–6 remedies for. -

CLAIMS AGAINST THIRD PARTIES Jeremy Bamford & Simon Passfield, Guildhall Chambers

CLAIMS AGAINST THIRD PARTIES Jeremy Bamford & Simon Passfield, Guildhall Chambers A. Introduction 1. This paper supports and provides the references for the Wonderland Ltd case study1 which will be considered during the seminar. 2. The aim of the case study is to explore claims which go beyond the usual fare of the office- holder’s statutory remedies by way of transactions at an undervalue, preference, s. 212 misfeasance claims, wrongful or fraudulent trading or transactions defrauding creditors. Instead we explore claims against third parties, where there has been a breach of the Companies Act and/or breach of fiduciary duty by directors, unlawful dividends being used as an example. B. Dividends 3. There are usually 3 potential grounds for challenging dividend payments: 3.1. the conventional technical claim made under the Companies legislation that dividends have not been paid out of profits available for that purpose and that the dividends have been paid in breach of the Companies legislation; 3.2. that the internal regulations of the company were breached and/or 3.3. breach of the common law maintenance of capital rule. We consider these in turn. B1 Part VIII CA 1985 4. In the case study the dividends were paid between 1 Sep 2007 and 1 March 2008. The relevant law is therefore Part VIII Companies Act 1985 (ss. 263 – 281 CA 1985)2. 5. A distribution of a company’s assets (which includes a dividend) can only be made out of profits available for the purpose (s. 263(1) CA 1985)3 being its accumulated, realised profits, so far as not previously utilised by distribution or capitalisation, less its accumulated, realised losses, so far as not previously written off in a reduction or reorganisation of capital duly made (s. -

PDF Print Version

HOUSE OF LORDS SESSION 2006–07 [2007] UKHL 34 on appeal from: [2005] EWCA Civ 389 OPINIONS OF THE LORDS OF APPEAL FOR JUDGMENT IN THE CAUSE Sempra Metals Limited (formerly Metallgesellschaft Limited) (Respondents) v. Her Majesty’s Commissioners of Inland Revenue and another (Appellants) Appellate Committee Lord Hope of Craighead Lord Nicholls of Birkenhead Lord Scott of Foscote Lord Walker of Gestingthorpe Lord Mance Counsel Appellants: Respondents: Ian Glick QC Laurence Rabinowitz QC Rupert Baldry Francis Fitzpatrick Gerry Facenna Steven Elliott (Instructed by Solicitor’s Office, HM Revenue and (Instructed by Slaughter & May) Customs ) Hearing dates: 1 and 2 November 2006 Further heard: 16 May 2007 ON WEDNESDAY 18 JULY 2007 HOUSE OF LORDS OPINIONS OF THE LORDS OF APPEAL FOR JUDGMENT IN THE CAUSE Sempra Metals Limited (formerly Metallgesellschaft Limited) (Respondents) v. Her Majesty’s Commissioners of Inland Revenue and another (Appellants) [2007] UKHL 34 LORD HOPE OF CRAIGHEAD My Lords, 1. This is a case about the award of interest. Questions about interest usually arise where the claim is presented as ancillary to a claim for a principal sum for which the court is asked to give judgment for the recovery of a debt or as damages. Less usually they can arise where interest is sought on a principal sum which has been paid before judgment. But in this case interest is the measure of the principal sum itself. 2. The question is how that sum should be measured. It is agreed that the calculation of interest should be the method of measurement for the sum that is to be awarded. -

Illegality: the 'Range of Factors' Test and Its Likely Impact

Learn - Develop - Connect legalpd.com Illegality: The 'range of factors' test and its likely impact Recorded: 12 October 2016 MASTERCLASS TRANSCRIPT Overview This 22-minute video examines the defence of illegality – from its 18th century origins to the radical changes made by the Supreme Court in 2016. Topics covered: • An overview of the doctrine of illegality • The origins of the defence of illegality • The extent to which the illegality defence is used today • The 1st limb: Was it illegal or immoral conduct? • The 2nd limb: Is the cause of action founded upon that illegality? • The facts of Patel v Mirza • The 'range of factors' test explained • The likely impact of the new test Cases referenced: • Holman v Johnson (1775) 1 Cowp. 341 • Everet v Williams (1725); see (1893) 9 L.Q.R. 197 • Beaumont v Ferrer [2016] EWCA Civ 768 • Les Laboratoires Servier v Apotex Inc [2014] UKSC 55 • Tinsley v Milligan [1994] 1 A.C. 340 • Patel v Mirza [2016] UKSC 42 Learn - Develop - Connect legalpd.com Presenter profile Carl Troman, 4 New Square Based at 4 New Square, Carl Troman is a commercial litigator with particular expertise and experience in disputes involving insurance, professional liability, classic and super cars (including motorsports), property damage and costs. He is also a formally accredited mediator and acts as an arbitrator. Carl is recommended as a leading junior in the fields of both insurance and professional negligence by Chambers & Partners 2016 – being described as "super-intelligent with great interpersonal skills", and "very user-friendly and good on tactics". Carl is also ranked in the 2016 Legal 500 and has been described as "outstanding" and "an accomplished advocate". -

Tracing Is a Process Not a Remedy

Tracing - Scenario 1(b): Trustee Mixes Trust Money - Tracing is a process not a remedy. With His Own In His Account, subsequently - It allows us to identify a new asset as the purchases property with some money in the substitute for the old (Foskett v McKeown). account, then exhausts remaining money. - Tracing follows the value of the beneficiaries - SOLUTION: Re Oatway: We get an property, not the property itself (following). exception to the rule in Hallett’s estate: if the wrongdoer purchased assets which still exist, Distinguishing Tracing; Following & Claiming then it is presumed that he did so with the - Following is the process of following the same stolen money and the beneficiaries are asset as it moves from hand to hand. entitled to the assets. - Claiming refers to the process of recovering property, or the substitute for that property (This - Scenario 1(c): Trustee Mixes Money With His refers to the Barnes v Addy; knowing receipt, Own In His Account, and makes payment in knowing assistance doctrine - MUST and out of that account. CONSIDER THIS AFTER TRACING). - SOLUTION: Lofts v McDonald: Lowest Intermediate Balance Rule: trust cannot claim more than the lowest intermediate balance Tracing at Common Law - credited to the wrongdoer’s bank account Tracing is not unique to equity, however at CL it - If it went up from the lowest point, that is requires that the property you are tracing is not the trust’s money. identifiable, giving rise to problems with banks. - - Although you are deprived of a proprietary Equity has developed rules for identifying remedy, not personal remedies. -

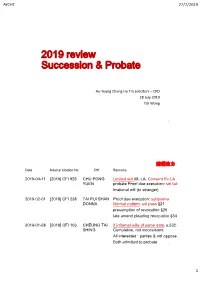

2019 Review Succession & Probate

AYCHT 27/7/2019 2019 review Succession & Probate Au‐Yeung Cheng Ho Tin solicitors –CPD 28 July 2019 Tak Wong 1 遺囑效力 Date Neutral Citation No Pltf Remarks 2019-04-11 [2019] CFI 925 CHU PONG Limited will 08, LA. Consent Rv LA YUEN probate Proof due execution: sol fail Irrational will (to stranger) 2019-02-01 [2019] CFI 238 TAI PUI SHAN Proof due execution: subpoena. DONNA Normal pattern. sol pass §21 presumption of revocation §26 late amend pleading revocation §34 2019-01-28 [2019] CFI 103 CHEUNG TAI 2 informal wills of same date. s.5(2) SHING Cumulative, not inconsistent. All interested : parties & not oppose. Both admitted to probate. 2 1 AYCHT 27/7/2019 遺囑效力 Date Neutral Citation No Pltf Remarks 2018-12-19 [2018] CFA 61 CHOY PO B v G evidence 3 limbs T/C.gap§11 CHUN fact-specific. No proper basis will instruction §18. will invalid 2019-04-18 [2019] CA 452 MOK HING Same B v G 3 limbs T/C. CHUNG fact-specific Yes proper basis. Choy Po Chun distinguished. Will instruction direct / rational Sol > sol firm. Will valid. 3 親屬關係 Date Neutral Citation No Pltf Remarks 2018-08-08 [2018] CA 491 LI CHEONG Natural dau, 1. DNA 2. copy B/C, rolled-up hearing directions 2018-10-18 [2018] CA 719 LI CHEONG Probate action in rem nature, O.15 r.13A, intended intervener, dismiss 2014-07-03 MOK HING CCL:spinster 1.no adopt §89 2.yes CHUNG i-tze 3.yes IEO s2(2)(c) 4.DWAE案 2018-10-19 [2018] CA 713 MOK HING CCL adoption v i-tze, apply to file CHUNG obituary notice, Ladd, dismiss 2019-04-18 [2019] CA 452 MOK HING CCL no formalities (adoption/i-tze) CHUNG §52, all 7 appeal grounds no merit. -

Apportionment of Liability and the Intentional Torts: the Time Is Right for Change

Dalhousie Law Journal Volume 7 Issue 1 Article 8 3-1-1982 Apportionment of Liability and the Intentional Torts: The Time is Right for Change Brian C. Crocker Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.schulichlaw.dal.ca/dlj Part of the Torts Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Brian C. Crocker, “Apportionment of Liability and the Intentional Torts: The Time is Right for Change”, Comment, (1982-1983) 7:1 DLJ 172. This Commentary is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Schulich Law Scholars. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dalhousie Law Journal by an authorized editor of Schulich Law Scholars. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Brian C. Crocker* Apportionment of Liability and the Intentional Torts: The Time is Right for Change I. Introduction In a tort action based solely on the Defendant's wrongful intentional conduct, both parties have been, until recently, at a decided disadvantage. There could be no apportionment of liability between the Plaintiff and Defendant. Fault concepts were seen in absolute terms. Either the Defendant was totally liable for the damages or he was not liable at all. Principles of apportionment of liability generally were not seen as applicable to the intentional torts. Thus, a Plaintiff's contributory fault was irrelevant in determining the Defendant's liability. Likewise, provocation was not a 'defence' and did not, in all jurisdictions, always reduce compensatory damages. Similarly for a Plaintiff the spectre was total success or total failure. -

The Superior Orders Defence: Embraced at Last?

THE NEW ZEALAND POSTGRADUATE LAW E-JOURNAL ISSUE 2 / 2005 THE SUPERIOR ORDERS DEFENCE: EMBRACED AT LAST? by Silva Hinek THE NEW ZEALAND POSTGRADUATE LAW E-JOURNAL (NZPGLEJ) - ISSUE 2 / 2005 THE SUPERIOR ORDERS DEFENCE: EMBRACED AT LAST? SILVA HINEK * For I believe and avow that one's duty toward one's people and fatherland stands above every other. To carry out this duty was for me an honour and the highest law. May this duty be supplanted in some happier future by an even higher one, by the duty toward humanity.1 ABSTRACT: The superior orders defence is one of the most controversial defences in international criminal law. Under national law a soldier is bound to obey the orders of his military superiors promptly and without hesitation. Yet, some orders may be illegal, whether under national, international or martial law. What should happen then to a soldier who commits a crime whilst following an illegal order? Currently, the Statute of the International Criminal Court contains a provision recognising the defence of superior orders in such cases. The purpose of this article is to examine the rationale behind the defence of superior orders, viewed through its troubled history, and also to appraise this very important step of codification taken by the international community. I INTRODUCTION The doctrine of superior orders is undoubtedly one of the most controversial and widely debated defences in international criminal law. The question of whether a soldier should be punished for his crimes when he claims to have been only following orders is fraught with difficult legal and moral issues. -

Unconscionability As an Underlying Concept in Equity

THE DENNING LAW JOURNAL UNCONSCIONABILITY AS A UNIFYING CONCEPT IN EQUITY Mark Pawlowski* ABSTRACT This article seeks to examine the extent to which a unified concept of unconscionability can be used to rationalise related doctrines of equity, in particular, in the areas of (1) unconscionable bargains, undue influence and duress (2) proprietary estoppel (3) knowing receipt liability and (4) relief against forfeitures. The conclusion is that such a process of amalgamation may provide a principled doctrinal basis for equity’s intervention which has already found favour in the English courts. INTRODUCTION A recent discernible trend in equity has been the willingness of the English courts to adopt a broader-based doctrine of unconscionability as underlying proprietary estoppel claims and the personal liability of a stranger to a trust who has knowingly received trust property in breach of trust. The decisions in Gillett v Holt,1 Jennings v Rice2 and Campbell v Griffin3 in the context of proprietary estoppel and Bank of Credit and Commerce International (Overseas) Ltd v Akindele4 on the subject of receipt liability, demonstrate the judiciary’s growing recognition that the concept of unconscionability provides a useful mechanism for affording equitable relief against the strict insistence on legal rights or unfair and oppressive conduct. This, in turn, prompts the question whether there are other areas which would benefit from a rationalisation of principles under the one umbrella of unconscionability. The process of amalgamation, it is submitted, would be particularly useful in areas where there are currently several related (but distinct) doctrines operating together so as to give rise to confusion and overlap in the same field of law. -

Complete Defences Partial Defences Defences to Criminal Charges

Defences to Criminal Charges Complete Defences - Something that will result in the acquittal of the accused person. Ie An absolute defence Partial Defences - Something that will allow a reduction in the seriousness of the charge or a reduction in punishment. Eg Reduction for murder to manslaughter. Text p 101 for examples Complete Defences Mental illness/insanity- In this case the person is incapable of having the Mens Rea. Possible outcomes- Release under supervision - Incapacitation in an institution Self Defence - Defence against attack is legal if no greater force than is reasonable/necessary is used. Eg No greater force than the threat defended against. How did the accused perceive the threat against them???? What level of force is reasonable???? Compulsion- 1) Necessity -- When the action taken by the accused is not as bad as the consequences of not acting. Eg Ships captain orders certain people into the lifeboats first, others drown. 2) Duress -- When a person is forced to commit a criminal act. Consent- Not a complete defence to murder. Cf Euthanasia. Common defence in sexual assault. Automatism- A complete defence based on being not in control of bodily actions. Eg Road accident because of a sneezing fit. Assault during sleep walking. Partial Defences Provocation- (In NSW only available as a defence to murder) Must be shown that the "reasonable person" would have been similarly provoked. May result in a reduction from murder to manslaughter. Crime Page 1 May result in a reduction from murder to manslaughter. Substantial impairment of responsibility (Diminished Responsibility)- Ie A less severe impairment than insanity or a psychological condition that predisposes a person to act in an unlawful way.