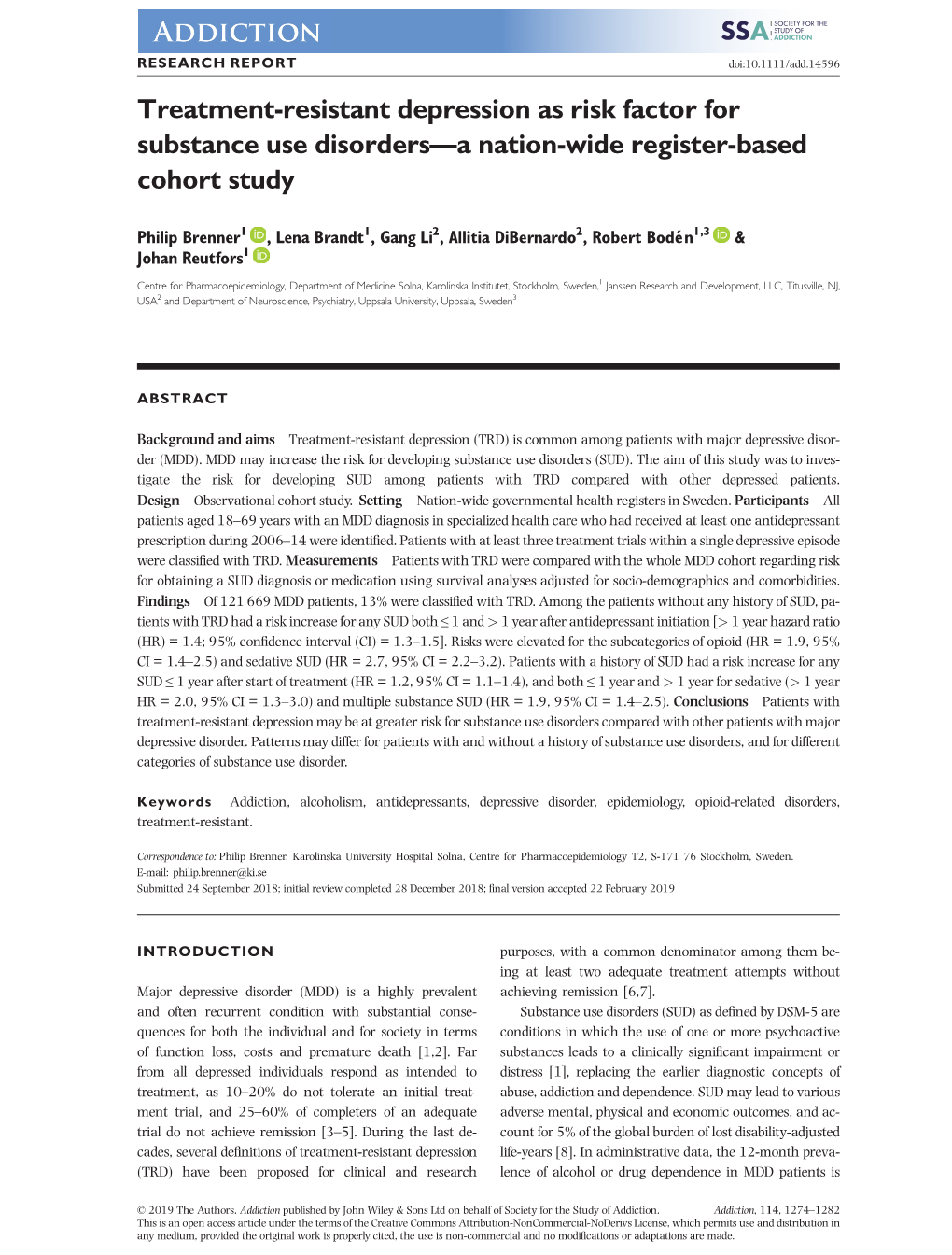

Treatment‐Resistant Depression As Risk Factor for Substance Use Disorders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix a Common Abbreviations Used in Medication

UNIVERSITY OF AMSTERDAM MASTERS THESIS Impact of Medication Grouping on Fall Risk Prediction in Elders: A Retrospective Analysis of MIMIC-III Critical Care Database Student: SRP Mentor: Noman Dormosh Dr. Martijn C. Schut Student No. 11412682 – SRP Tutor: Prof. dr. Ameen Abu-Hanna SRP Address: Amsterdam University Medical Center - Location AMC Department Medical Informatics Meibergdreef 9, 1105 AZ Amsterdam Practice teaching period: November 2018 - June 2019 A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Medical Informatics iii Abstract Background: Falls are the leading cause of injury in elderly patients. Risk factors for falls in- cluding among others history of falls, old age, and female gender. Research studies have also linked certain medications with an increased risk of fall in what is called fall-risk-increasing drugs (FRIDs), such as psychotropics and cardiovascular drugs. However, there is a lack of consistency in the definitions of FRIDs between the studies and many studies did not use any systematic classification for medications. Objective: The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of grouping medications at different levels of granularity of a medication classification system on the performance of fall risk prediction models. Methods: This is a retrospective analysis of the MIMIC-III cohort database. We created seven prediction models including demographic, comorbidity and medication variables. Medica- tions were grouped using the anatomical therapeutic chemical classification system (ATC) starting from the most specific scope of medications and moving up to the more generic groups: one model used individual medications (ATC level 5), four models used medication grouping at levels one, two, three and four of the ATC and one model did not include med- ications. -

Medication Assisted Treatment MAT

Medication Assisted Treatment MAT The Root Center provides medication assisted treatment (MAT) for substance use disorders to those who qualify. MAT uses medications in combination with counseling and behavioral therapies to provide a “whole-patient” approach. The ultimate goal of MAT is full recovery, including the ability to live a self-directed life. This treatment approach has been shown to: improve patient survival, increase retention in treatment, decrease illicit opiate and other drug use as well as reduce other criminal activity among people with substance use disorders, increase patients’ ability to gain and maintain employment, and improve birth outcomes among women who have substance use disorders and are pregnant. These approved medications assist with urges, cravings, withdrawal symptoms, and some act as a blocking mechanism for the euphoric effects of alcohol and opioids. Currently, Root offers methadone for opioid use disorder and is considering adding other medications listed below. Opioid Use Disorder Overdose Prevention Methadone Methadone is an opioid treatment medication that reduces withdrawal Naloxone symptoms in people addicted to heroin or other narcotic drugs without Naloxone is a medication which causing the “high” associated with the drug. saves lives by reversing the effects of an opioid overdose. Root Center Methadone is used as a pain reliever and as part of drug addiction patients, their friends and family detoxification and maintenance programs. It is available only from members, can receive a prescription a certified pharmacy. for Naloxone as early as the initial evaluation and throughout treatment. Buprenorphine The medication is administered Buprenorphine is an opioid treatment medication and the combination at the time of the overdose. -

Evidence-Based Guidelines for the Pharmacological Management of Substance Abuse, Harmful Use, Addictio

444324 JOP0010.1177/0269881112444324Lingford-Hughes et al.Journal of Psychopharmacology 2012 BAP Guidelines BAP updated guidelines: evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological management of substance abuse, Journal of Psychopharmacology 0(0) 1 –54 harmful use, addiction and comorbidity: © The Author(s) 2012 Reprints and permission: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav recommendations from BAP DOI: 10.1177/0269881112444324 jop.sagepub.com AR Lingford-Hughes1, S Welch2, L Peters3 and DJ Nutt 1 With expert reviewers (in alphabetical order): Ball D, Buntwal N, Chick J, Crome I, Daly C, Dar K, Day E, Duka T, Finch E, Law F, Marshall EJ, Munafo M, Myles J, Porter S, Raistrick D, Reed LJ, Reid A, Sell L, Sinclair J, Tyrer P, West R, Williams T, Winstock A Abstract The British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines for the treatment of substance abuse, harmful use, addiction and comorbidity with psychiatric disorders primarily focus on their pharmacological management. They are based explicitly on the available evidence and presented as recommendations to aid clinical decision making for practitioners alongside a detailed review of the evidence. A consensus meeting, involving experts in the treatment of these disorders, reviewed key areas and considered the strength of the evidence and clinical implications. The guidelines were drawn up after feedback from participants. The guidelines primarily cover the pharmacological management of withdrawal, short- and long-term substitution, maintenance of abstinence and prevention of complications, where appropriate, for substance abuse or harmful use or addiction as well management in pregnancy, comorbidity with psychiatric disorders and in younger and older people. Keywords Substance misuse, addiction, guidelines, pharmacotherapy, comorbidity Introduction guidelines (e.g. -

Michael F. Weaver, MD, DFASAM PRESENT TITLE

February 1, 2021 CURRICULUM VITAE NAME: Michael F. Weaver, M.D., DFASAM PRESENT TITLE: Professor of Psychiatry WORK ADDRESS: Center for Neurobehavioral Research on Addiction Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences McGovern Medical School The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston 1941 East Road, BBSB 1222 Houston, TX 77054 713-486-2558 UNDERGRADUATE EDUCATION: B.S., Natural Sciences, 1991 University of Akron Akron, OH GRADUATE EDUCATION: Doctor of Medicine, 1993 Northeast Ohio Medical University Rootstown, OH POSTGRADUATE TRAINING: Residency, Internal Medicine, 1993-1996 Virginia Commonwealth University Health System Richmond, VA Hoff Fellowship in Substance Abuse Medicine, 1996-1997 Virginia Commonwealth University Health System Richmond, VA ACADEMIC AND ADMINISTRATIVE APPOINTMENTS: Instructor, 1996-1997 Internal Medicine and Psychiatry VCU Richmond, VA Assistant Professor, 1997-2006 Internal Medicine, Psychiatry and Pharmacy VCU Richmond, VA Program Director, Addiction Medicine Fellowship, 2001-2003 Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine, Richmond, Virginia 1 February 1, 2021 Associate Professor with Tenure, 2006-2012 Internal Medicine, Psychiatry and Pharmacy VCU Richmond, VA Professor with Tenure, 2012-2014 Internal Medicine, Psychiatry and Pharmacy Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) Richmond, VA Medical Director, 2013-2014 Virginia Health Practitioners Monitoring Program Richmond, VA Professor, 2014-present Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences McGovern Medical School The University -

Treatment of Patients with Substance Use Disorders Second Edition

PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR THE Treatment of Patients With Substance Use Disorders Second Edition WORK GROUP ON SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS Herbert D. Kleber, M.D., Chair Roger D. Weiss, M.D., Vice-Chair Raymond F. Anton Jr., M.D. To n y P. G e o r ge , M .D . Shelly F. Greenfield, M.D., M.P.H. Thomas R. Kosten, M.D. Charles P. O’Brien, M.D., Ph.D. Bruce J. Rounsaville, M.D. Eric C. Strain, M.D. Douglas M. Ziedonis, M.D. Grace Hennessy, M.D. (Consultant) Hilary Smith Connery, M.D., Ph.D. (Consultant) This practice guideline was approved in December 2005 and published in August 2006. A guideline watch, summarizing significant developments in the scientific literature since publication of this guideline, may be available in the Psychiatric Practice section of the APA web site at www.psych.org. 1 Copyright 2010, American Psychiatric Association. APA makes this practice guideline freely available to promote its dissemination and use; however, copyright protections are enforced in full. No part of this guideline may be reproduced except as permitted under Sections 107 and 108 of U.S. Copyright Act. For permission for reuse, visit APPI Permissions & Licensing Center at http://www.appi.org/CustomerService/Pages/Permissions.aspx. AMERICAN PSYCHIATRIC ASSOCIATION STEERING COMMITTEE ON PRACTICE GUIDELINES John S. McIntyre, M.D., Chair Sara C. Charles, M.D., Vice-Chair Daniel J. Anzia, M.D. Ian A. Cook, M.D. Molly T. Finnerty, M.D. Bradley R. Johnson, M.D. James E. Nininger, M.D. Paul Summergrad, M.D. Sherwyn M. -

Acamprosate in the Treatment of Binge Eating Disorder: a Placebo-Controlled Trial

CE ACTIVITY Acamprosate in the Treatment of Binge Eating Disorder: A Placebo-Controlled Trial Susan L. McElroy, MD1* ABSTRACT obsessive-compulsiveness of binge eat- 1 Objective: To assess preliminarily the ing, food craving, and quality of life. Anna I. Guerdjikova, PhD effectiveness of acamprosate in binge Among completers, weight and BMI 1 Erin L. Winstanley, PhD eating disorder (BED). decreased slightly in the acamprosate 1 group but increased in the placebo Anne M. O’Melia, MD Method: In this 10-week, randomized, 1 group. Nicole Mori, CNP placebo-controlled, flexible dose trial, 40 1 Jessica McCoy, BA outpatients with BED received acampro- Discussion: Although acamprosate did Paul E. Keck Jr., MD1 sate (N 5 20) or placebo (N 5 20). The not separate from placebo on any out- James I. Hudson, MD, ScD2 primary outcome measure was binge eat- come variable in the longitudinal analy- ing episode frequency. sis, results of the endpoint and completer analyses suggest the drug may have Results: While acamprosate was not some utility in BED. VC 2010 by Wiley associated with a significantly greater Periodicals, Inc. rate of reduction in binge eating episode frequency or any other measure in the Keywords: acamprosate; binge eating primary longitudinal analysis, in the end- disorder; obesity; glutamate point analysis it was associated with stat- istically significant improvements in binge day frequency and measures of (Int J Eat Disord 2011; 44:81–90) Introduction The treatment of BED remains a challenge.5 Cogni- tive behavioral and interpersonal therapies and selec- Binge eating disorder (BED), characterized by recur- tive serotonin-reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepres- rent binge-eating episodes without inappropriate sants are effective for reducing binge eating, but usu- 1 compensatory weight loss behaviors, is an impor- ally are not associated with clinically significant tant public health problem. -

![Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8870/ehealth-dsi-ehdsi-v2-2-2-or-ehealth-dsi-master-value-set-1028870.webp)

Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set

MTC eHealth DSI [eHDSI v2.2.2-OR] eHealth DSI – Master Value Set Catalogue Responsible : eHDSI Solution Provider PublishDate : Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 1 of 490 MTC Table of Contents epSOSActiveIngredient 4 epSOSAdministrativeGender 148 epSOSAdverseEventType 149 epSOSAllergenNoDrugs 150 epSOSBloodGroup 155 epSOSBloodPressure 156 epSOSCodeNoMedication 157 epSOSCodeProb 158 epSOSConfidentiality 159 epSOSCountry 160 epSOSDisplayLabel 167 epSOSDocumentCode 170 epSOSDoseForm 171 epSOSHealthcareProfessionalRoles 184 epSOSIllnessesandDisorders 186 epSOSLanguage 448 epSOSMedicalDevices 458 epSOSNullFavor 461 epSOSPackage 462 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 2 of 490 MTC epSOSPersonalRelationship 464 epSOSPregnancyInformation 466 epSOSProcedures 467 epSOSReactionAllergy 470 epSOSResolutionOutcome 472 epSOSRoleClass 473 epSOSRouteofAdministration 474 epSOSSections 477 epSOSSeverity 478 epSOSSocialHistory 479 epSOSStatusCode 480 epSOSSubstitutionCode 481 epSOSTelecomAddress 482 epSOSTimingEvent 483 epSOSUnits 484 epSOSUnknownInformation 487 epSOSVaccine 488 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 3 of 490 MTC epSOSActiveIngredient epSOSActiveIngredient Value Set ID 1.3.6.1.4.1.12559.11.10.1.3.1.42.24 TRANSLATIONS Code System ID Code System Version Concept Code Description (FSN) 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 -

The Use of Central Nervous System Active Drugs During Pregnancy

Pharmaceuticals 2013, 6, 1221-1286; doi:10.3390/ph6101221 OPEN ACCESS pharmaceuticals ISSN 1424-8247 www.mdpi.com/journal/pharmaceuticals Review The Use of Central Nervous System Active Drugs During Pregnancy Bengt Källén 1,*, Natalia Borg 2 and Margareta Reis 3 1 Tornblad Institute, Lund University, Biskopsgatan 7, Lund SE-223 62, Sweden 2 Department of Statistics, Monitoring and Analyses, National Board of Health and Welfare, Stockholm SE-106 30, Sweden; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 Department of Medical and Health Sciences, Clinical Pharmacology, Linköping University, Linköping SE-581 85, Sweden; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +46-46-222-7536, Fax: +46-46-222-4226. Received: 1 July 2013; in revised form: 10 September 2013 / Accepted: 25 September 2013 / Published: 10 October 2013 Abstract: CNS-active drugs are used relatively often during pregnancy. Use during early pregnancy may increase the risk of a congenital malformation; use during the later part of pregnancy may be associated with preterm birth, intrauterine growth disturbances and neonatal morbidity. There is also a possibility that drug exposure can affect brain development with long-term neuropsychological harm as a result. This paper summarizes the literature on such drugs used during pregnancy: opioids, anticonvulsants, drugs used for Parkinson’s disease, neuroleptics, sedatives and hypnotics, antidepressants, psychostimulants, and some other CNS-active drugs. In addition to an overview of the literature, data from the Swedish Medical Birth Register (1996–2011) are presented. The exposure data are either based on midwife interviews towards the end of the first trimester or on linkage with a prescribed drug register. -

Estonian Statistics on Medicines 2016 1/41

Estonian Statistics on Medicines 2016 ATC code ATC group / Active substance (rout of admin.) Quantity sold Unit DDD Unit DDD/1000/ day A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 167,8985 A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 0,0738 A01A STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 0,0738 A01AB Antiinfectives and antiseptics for local oral treatment 0,0738 A01AB09 Miconazole (O) 7088 g 0,2 g 0,0738 A01AB12 Hexetidine (O) 1951200 ml A01AB81 Neomycin+ Benzocaine (dental) 30200 pieces A01AB82 Demeclocycline+ Triamcinolone (dental) 680 g A01AC Corticosteroids for local oral treatment A01AC81 Dexamethasone+ Thymol (dental) 3094 ml A01AD Other agents for local oral treatment A01AD80 Lidocaine+ Cetylpyridinium chloride (gingival) 227150 g A01AD81 Lidocaine+ Cetrimide (O) 30900 g A01AD82 Choline salicylate (O) 864720 pieces A01AD83 Lidocaine+ Chamomille extract (O) 370080 g A01AD90 Lidocaine+ Paraformaldehyde (dental) 405 g A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 47,1312 A02A ANTACIDS 1,0133 Combinations and complexes of aluminium, calcium and A02AD 1,0133 magnesium compounds A02AD81 Aluminium hydroxide+ Magnesium hydroxide (O) 811120 pieces 10 pieces 0,1689 A02AD81 Aluminium hydroxide+ Magnesium hydroxide (O) 3101974 ml 50 ml 0,1292 A02AD83 Calcium carbonate+ Magnesium carbonate (O) 3434232 pieces 10 pieces 0,7152 DRUGS FOR PEPTIC ULCER AND GASTRO- A02B 46,1179 OESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE (GORD) A02BA H2-receptor antagonists 2,3855 A02BA02 Ranitidine (O) 340327,5 g 0,3 g 2,3624 A02BA02 Ranitidine (P) 3318,25 g 0,3 g 0,0230 A02BC Proton pump inhibitors 43,7324 A02BC01 Omeprazole -

Treating Substance Abuse •

• Treating Substance rain Abuse Theory and Technique usance Third Edition Theor.y and USeTechmque Edited by Scott 1. Walters Frederick Rotgers THIRD EDITIO ~ THE GUILFORD PRESS . New York London 2B2 TREATING SUBSTANCE ABUSE Chapter 11 This chapter first presents the basics of brain function, including the neurotransmitters and pathways involved in substance abuse. This under standing provides the foundation for the subsequent presentation of medi Neurobiological Bases cations used to treat addictive disorders. This chapter focuses on medi cations approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for of Addiction Treatment alcohol dependence and opioid dependence with an overview of promis ing new developments for stimulant and cannabis dependence. (Carroll & Kiluk. Chapter 12, this volume) in this book talks more specifically about Philip H. Chung integrating psychotherapy with pharmacotherapy. Julie D. Ross Sidarth Wakhlu Brain Basics Bryon Adinoff Neurons and the Brain MicroscopicaHy, the brain is composed of a collection of cells, or neurons, that signal one another both chemically and electrically. Electrical signals are lIsed to communicate within cells, and chemical signals are used to com municate between cells. Most neurons have a characteristic structure that consists of a globular cell body with numerous long, spindly projections coming off the central cell body (Figure 11.1). These projections are used in the process of signaling between neurons and receive communications from their sometimes-distant cell bodies. The axon of a signaling cell projects to ovcr the past two decades stunning progress has been made in the dendrite of the receiving cell, and the twO projections come into dose understanding the psychopathology of addiction. -

W08. Update in Addiction Medicine

Canadian Society of Internal Medicine Annual Meeting 2017 Toronto, ON Update in Addiction Medicine Rajesh Gupta University of Toronto Division of GIM, St. Michael’s Hospital CSIM Annual Meeting 2017 The following presentation represents the views of the speaker at the time of the presentation. This information is meant for educational purposes, and should not replace other sources of information or your medical judgment. Learning Objectives: 1. Advise patients of the effectiveness and risks of buprenorphine and methadone in the treatment of opioid use disorder 2. Develop a process for providing safe transitions for patients on buprenorphine or methadone 3. Select an appropriate pharmacologic agent for treating alcohol use disorder . CSIM Annual Meeting 2017 Conflict Disclosures I have no conflicts to declare CSIM Annual Meeting 2017 Some of the drugs, devices, or treatment modalities Mentioned in this presentation are: Buprenorphine/naloxone, methadone Naltrexone, gabapentin, acamprosate Baclofen, ondansetron, topiramate I intend to make off-label therapeutic recommendations for medications Scope of Hospital-based OAST • Survey • Development of the SMH addiction team Case 1 30 yo woman with IV hydromorphone addiction presents with pneumonia requiring IV antibiotics and supplemental O2. She uses hydromorphone 8 mg IV q3h, bought on the street. She complains of vague chest pain over the area of the pneumonia. She is requesting IV hydromorphone 8 mg q3h for the chest pain. She suggests she will have to get it somehow, to prevent withdrawal and ongoing pain, etc. What do you recommend? Case 2 50 yo man with opioid use disorder in remission x 3 years on methadone 75 mg daily. -

View the Scientific Program Abstracts of the ACAAM 2020 Annual Meeting

Scientific Program Abstracts of the ACAAM 2020 Annual Meeting AMERICAN COLLEGE OF ACADEMIC ADDICTION OF ACADEMIC MEDICINE AMERICAN COLLEGE ADDICTION OF ACADEMIC MEDICINE AMERICAN COLLEGE ADDICTION OF ACADEMIC MEDICINE AMERICAN COLLEGE ADDICTION OF ACADEMIC MEDICINE AMERICAN COLLEGE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF ACADEMIC ADDICTION MEDICINE OF ACADEMIC AMERICAN COLLEGE March 24, 2020 On behalf of the Poster Sub-Committee for the Annual Meeting of The American College of Academic Addiction Medicine I am writing with several updates about the canceled 2020 Annual Meeting poster session to which you had been accepted. 2020 Meeting & Poster Session The 2020 meeting previously scheduled for April in Denver will not be rescheduled as an in- person meeting. We are currently re-imagining the meeting as a series of bi-monthly online gatherings to stay in touch and share important information. One possibility is to use the June gathering to showcase your posters and celebrate the graduates. Expect to receive more information after the current public health issues become clearer and we work out the logistics. 2020 Poster Session Winners Poster session winners were selected prior to cancellation of the meeting and we would like to recognize them here: Emily Buirkle, MD - Rutgers University Co-Author: Erin Zerbo, MD Buprenorphine induction with microdosing: A review of the literature Haileigh Ross, OD - Ohio Health Grant Medical Center Co-Author: Krisanna Deppen, MD A novel case of injectable buprenorphine for opioid use disorder in pregnancy Kumar Vasudevan, MD - NYU School of Medicine Co-Authors: Mia Malone; Ryan McDonald, MA; Anna Cheng; Michael Matteo, CASAC; Monica Katyal, JD MPH; Jasdeep Mangat, MD; Jonathan Giftos, MD; Ross MacDonald, MD; Joshua D.