BMJ Open Is Committed to Open Peer Review. As Part of This Commitment We Make the Peer Review History of Every Article We Publish Publicly Available

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vasodilators for Primary Raynaud's Phenomenon

Vasodilators for primary Raynaud's phenomenon Author Su, KYC, Sharma, M, Kim, HJ, Kaganov, E, Hughes, I, Abdeen, MH, Ng, JHK Published 2021 Journal Title Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Version Version of Record (VoR) DOI https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006687.pub4 Copyright Statement © 2021 The Cochrane Collaboration. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. This review is published as a Cochrane Review in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2021, Issue 5. Art. No.: CD006687.. Cochrane Reviews are regularly updated as new evidence emerges and in response to comments and criticisms, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews should be consulted for the most recent version of the Review. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/405317 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Cochrane Library Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Vasodilators for primary Raynaud's phenomenon (Review) Su KYC, Sharma M, Kim HJ, Kaganov E, Hughes I, Abdeen MH, Ng JHK Su KYC, Sharma M, Kim HJ, Kaganov E, Hughes I, Abdeen MH, Ng JH. Vasodilators for primary Raynaud's phenomenon. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2021, Issue 5. Art. No.: CD006687. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006687.pub4. www.cochranelibrary.com Vasodilators for primary Raynaud's phenomenon (Review) Copyright © 2021 The Cochrane Collaboration. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Cochrane Trusted evidence. Informed decisions. Library Better health. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S HEADER........................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

The National Drugs List

^ ^ ^ ^ ^[ ^ The National Drugs List Of Syrian Arab Republic Sexth Edition 2006 ! " # "$ % &'() " # * +$, -. / & 0 /+12 3 4" 5 "$ . "$ 67"5,) 0 " /! !2 4? @ % 88 9 3: " # "$ ;+<=2 – G# H H2 I) – 6( – 65 : A B C "5 : , D )* . J!* HK"3 H"$ T ) 4 B K<) +$ LMA N O 3 4P<B &Q / RS ) H< C4VH /430 / 1988 V W* < C A GQ ") 4V / 1000 / C4VH /820 / 2001 V XX K<# C ,V /500 / 1992 V "!X V /946 / 2004 V Z < C V /914 / 2003 V ) < ] +$, [2 / ,) @# @ S%Q2 J"= [ &<\ @ +$ LMA 1 O \ . S X '( ^ & M_ `AB @ &' 3 4" + @ V= 4 )\ " : N " # "$ 6 ) G" 3Q + a C G /<"B d3: C K7 e , fM 4 Q b"$ " < $\ c"7: 5) G . HHH3Q J # Hg ' V"h 6< G* H5 !" # $%" & $' ,* ( )* + 2 ا اوا ادو +% 5 j 2 i1 6 B J' 6<X " 6"[ i2 "$ "< * i3 10 6 i4 11 6! ^ i5 13 6<X "!# * i6 15 7 G!, 6 - k 24"$d dl ?K V *4V h 63[46 ' i8 19 Adl 20 "( 2 i9 20 G Q) 6 i10 20 a 6 m[, 6 i11 21 ?K V $n i12 21 "% * i13 23 b+ 6 i14 23 oe C * i15 24 !, 2 6\ i16 25 C V pq * i17 26 ( S 6) 1, ++ &"r i19 3 +% 27 G 6 ""% i19 28 ^ Ks 2 i20 31 % Ks 2 i21 32 s * i22 35 " " * i23 37 "$ * i24 38 6" i25 39 V t h Gu* v!* 2 i26 39 ( 2 i27 40 B w< Ks 2 i28 40 d C &"r i29 42 "' 6 i30 42 " * i31 42 ":< * i32 5 ./ 0" -33 4 : ANAESTHETICS $ 1 2 -1 :GENERAL ANAESTHETICS AND OXYGEN 4 $1 2 2- ATRACURIUM BESYLATE DROPERIDOL ETHER FENTANYL HALOTHANE ISOFLURANE KETAMINE HCL NITROUS OXIDE OXYGEN PROPOFOL REMIFENTANIL SEVOFLURANE SUFENTANIL THIOPENTAL :LOCAL ANAESTHETICS !67$1 2 -5 AMYLEINE HCL=AMYLOCAINE ARTICAINE BENZOCAINE BUPIVACAINE CINCHOCAINE LIDOCAINE MEPIVACAINE OXETHAZAINE PRAMOXINE PRILOCAINE PREOPERATIVE MEDICATION & SEDATION FOR 9*: ;< " 2 -8 : : SHORT -TERM PROCEDURES ATROPINE DIAZEPAM INJ. -

Upregulation of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-Α And

Upregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α and the lipid metabolism pathway promotes carcinogenesis of ampullary cancer Chih-Yang Wang, Ying-Jui Chao, Yi-Ling Chen, Tzu-Wen Wang, Nam Nhut Phan, Hui-Ping Hsu, Yan-Shen Shan, Ming-Derg Lai 1 Supplementary Table 1. Demographics and clinical outcomes of five patients with ampullary cancer Time of Tumor Time to Age Differentia survival/ Sex Staging size Morphology Recurrence recurrence Condition (years) tion expired (cm) (months) (months) T2N0, 51 F 211 Polypoid Unknown No -- Survived 193 stage Ib T2N0, 2.41.5 58 F Mixed Good Yes 14 Expired 17 stage Ib 0.6 T3N0, 4.53.5 68 M Polypoid Good No -- Survived 162 stage IIA 1.2 T3N0, 66 M 110.8 Ulcerative Good Yes 64 Expired 227 stage IIA T3N0, 60 M 21.81 Mixed Moderate Yes 5.6 Expired 16.7 stage IIA 2 Supplementary Table 2. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis of an ampullary cancer microarray using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID). This table contains only pathways with p values that ranged 0.0001~0.05. KEGG Pathway p value Genes Pentose and 1.50E-04 UGT1A6, CRYL1, UGT1A8, AKR1B1, UGT2B11, UGT2A3, glucuronate UGT2B10, UGT2B7, XYLB interconversions Drug metabolism 1.63E-04 CYP3A4, XDH, UGT1A6, CYP3A5, CES2, CYP3A7, UGT1A8, NAT2, UGT2B11, DPYD, UGT2A3, UGT2B10, UGT2B7 Maturity-onset 2.43E-04 HNF1A, HNF4A, SLC2A2, PKLR, NEUROD1, HNF4G, diabetes of the PDX1, NR5A2, NKX2-2 young Starch and sucrose 6.03E-04 GBA3, UGT1A6, G6PC, UGT1A8, ENPP3, MGAM, SI, metabolism -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0110428A1 De Juan Et Al

US 200601 10428A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0110428A1 de Juan et al. (43) Pub. Date: May 25, 2006 (54) METHODS AND DEVICES FOR THE Publication Classification TREATMENT OF OCULAR CONDITIONS (51) Int. Cl. (76) Inventors: Eugene de Juan, LaCanada, CA (US); A6F 2/00 (2006.01) Signe E. Varner, Los Angeles, CA (52) U.S. Cl. .............................................................. 424/427 (US); Laurie R. Lawin, New Brighton, MN (US) (57) ABSTRACT Correspondence Address: Featured is a method for instilling one or more bioactive SCOTT PRIBNOW agents into ocular tissue within an eye of a patient for the Kagan Binder, PLLC treatment of an ocular condition, the method comprising Suite 200 concurrently using at least two of the following bioactive 221 Main Street North agent delivery methods (A)-(C): Stillwater, MN 55082 (US) (A) implanting a Sustained release delivery device com (21) Appl. No.: 11/175,850 prising one or more bioactive agents in a posterior region of the eye so that it delivers the one or more (22) Filed: Jul. 5, 2005 bioactive agents into the vitreous humor of the eye; (B) instilling (e.g., injecting or implanting) one or more Related U.S. Application Data bioactive agents Subretinally; and (60) Provisional application No. 60/585,236, filed on Jul. (C) instilling (e.g., injecting or delivering by ocular ion 2, 2004. Provisional application No. 60/669,701, filed tophoresis) one or more bioactive agents into the Vit on Apr. 8, 2005. reous humor of the eye. Patent Application Publication May 25, 2006 Sheet 1 of 22 US 2006/0110428A1 R 2 2 C.6 Fig. -

Zebrafish Behavioral Profiling Links Drugs to Biological Targets and Rest/Wake Regulation

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/327/5963/348/DC1 Supporting Online Material for Zebrafish Behavioral Profiling Links Drugs to Biological Targets and Rest/Wake Regulation Jason Rihel,* David A. Prober, Anthony Arvanites, Kelvin Lam, Steven Zimmerman, Sumin Jang, Stephen J. Haggarty, David Kokel, Lee L. Rubin, Randall T. Peterson, Alexander F. Schier* *To whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: [email protected] (A.F.S.); [email protected] (J.R.) Published 15 January 2010, Science 327, 348 (2010) DOI: 10.1126/science.1183090 This PDF file includes: Materials and Methods SOM Text Figs. S1 to S18 Table S1 References Supporting Online Material Table of Contents Materials and Methods, pages 2-4 Supplemental Text 1-7, pages 5-10 Text 1. Psychotropic Drug Discovery, page 5 Text 2. Dose, pages 5-6 Text 3. Therapeutic Classes of Drugs Induce Correlated Behaviors, page 6 Text 4. Polypharmacology, pages 6-7 Text 5. Pharmacological Conservation, pages 7-9 Text 6. Non-overlapping Regulation of Rest/Wake States, page 9 Text 7. High Throughput Behavioral Screening in Practice, page 10 Supplemental Figure Legends, pages 11-14 Figure S1. Expanded hierarchical clustering analysis, pages 15-18 Figure S2. Hierarchical and k-means clustering yield similar cluster architectures, page 19 Figure S3. Expanded k-means clustergram, pages 20-23 Figure S4. Behavioral fingerprints are stable across a range of doses, page 24 Figure S5. Compounds that share biological targets have highly correlated behavioral fingerprints, page 25 Figure S6. Examples of compounds that share biological targets and/or structural similarity that give similar behavioral profiles, page 26 Figure S7. -

)&F1y3x PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX to THE

)&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE )&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 3 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. Product CAS No. Product CAS No. ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACTODIGIN 36983-69-4 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ADAFENOXATE 82168-26-1 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ADAMEXINE 54785-02-3 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ADAPALENE 106685-40-9 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ADAPROLOL 101479-70-3 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ADATANSERIN 127266-56-2 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ADEFOVIR 106941-25-7 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ADELMIDROL 1675-66-7 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 ADEMETIONINE 17176-17-9 ACAPRAZINE 55485-20-6 ADENOSINE PHOSPHATE 61-19-8 ACARBOSE 56180-94-0 ADIBENDAN 100510-33-6 ACEBROCHOL 514-50-1 ADICILLIN 525-94-0 ACEBURIC ACID 26976-72-7 ADIMOLOL 78459-19-5 ACEBUTOLOL 37517-30-9 ADINAZOLAM 37115-32-5 ACECAINIDE 32795-44-1 ADIPHENINE 64-95-9 ACECARBROMAL 77-66-7 ADIPIODONE 606-17-7 ACECLIDINE 827-61-2 ADITEREN 56066-19-4 ACECLOFENAC 89796-99-6 ADITOPRIM 56066-63-8 ACEDAPSONE 77-46-3 ADOSOPINE 88124-26-9 ACEDIASULFONE SODIUM 127-60-6 ADOZELESIN 110314-48-2 ACEDOBEN 556-08-1 ADRAFINIL 63547-13-7 ACEFLURANOL 80595-73-9 ADRENALONE -

Pharmacy and Poisons (Third and Fourth Schedule Amendment) Order 2017

Q UO N T FA R U T A F E BERMUDA PHARMACY AND POISONS (THIRD AND FOURTH SCHEDULE AMENDMENT) ORDER 2017 BR 111 / 2017 The Minister responsible for health, in exercise of the power conferred by section 48A(1) of the Pharmacy and Poisons Act 1979, makes the following Order: Citation 1 This Order may be cited as the Pharmacy and Poisons (Third and Fourth Schedule Amendment) Order 2017. Repeals and replaces the Third and Fourth Schedule of the Pharmacy and Poisons Act 1979 2 The Third and Fourth Schedules to the Pharmacy and Poisons Act 1979 are repealed and replaced with— “THIRD SCHEDULE (Sections 25(6); 27(1))) DRUGS OBTAINABLE ONLY ON PRESCRIPTION EXCEPT WHERE SPECIFIED IN THE FOURTH SCHEDULE (PART I AND PART II) Note: The following annotations used in this Schedule have the following meanings: md (maximum dose) i.e. the maximum quantity of the substance contained in the amount of a medicinal product which is recommended to be taken or administered at any one time. 1 PHARMACY AND POISONS (THIRD AND FOURTH SCHEDULE AMENDMENT) ORDER 2017 mdd (maximum daily dose) i.e. the maximum quantity of the substance that is contained in the amount of a medicinal product which is recommended to be taken or administered in any period of 24 hours. mg milligram ms (maximum strength) i.e. either or, if so specified, both of the following: (a) the maximum quantity of the substance by weight or volume that is contained in the dosage unit of a medicinal product; or (b) the maximum percentage of the substance contained in a medicinal product calculated in terms of w/w, w/v, v/w, or v/v, as appropriate. -

Wo 2010/075090 A2

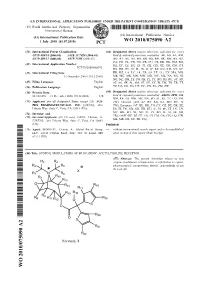

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date 1 July 2010 (01.07.2010) WO 2010/075090 A2 (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every C07D 409/14 (2006.01) A61K 31/7028 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, C07D 409/12 (2006.01) A61P 11/06 (2006.01) AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, (21) International Application Number: DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, PCT/US2009/068073 HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, (22) International Filing Date: KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, 15 December 2009 (15.12.2009) ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, RO, RS, RU, SC, SD, (25) Filing Language: English SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, (26) Publication Language: English TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (30) Priority Data: (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every 61/122,478 15 December 2008 (15.12.2008) US kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, GM, KE, LS, MW, MZ, NA, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): AUS- ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, MD, RU, TJ, PEX PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. -

Marie Louise De Bruin Drug Induced Arrhythmias

Marie Louise De Bruin drug induced arrhythmias Quantifying the problem Cover design: Tom Frantzen CIP-gegevens Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag De Bruin, Marie Louise Drug-induced arrhythmias, quantifying the problem / Marie Louise De Bruin Thesis Utrecht - with ref.- with summary in Dutch ISBN: 90-808203-3-4 © Marie Louise De Bruin drug-induced arrhythmias, quantifying the problem Geneesmiddel-geïnduceerde hartritmestoornissen, kwantificering van het probleem (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Utrecht op gezag van de Rector Magnificus Prof. dr W.H. Gispen, ingevolge het besluit van het College voor Promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op woensdag 1 december 2004 des namiddags om 14.30 uur door Marie Louise De Bruin Geboren op 1 april 1974 te Haarlem promotores Prof. dr H.G.M. Leufkens Utrecht Institute for Pharmaceutical Sciences (UIPS), Department of Pharmaco- epidemiology and Pharmacotherapy, Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands Prof. dr A.W. Hoes Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Center, Utrecht, the Netherlands The work in this thesis was performed at the Department of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacotherapy of the Utrecht Institute for Pharmaceutical Sciences (Utrecht) and the Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care (Utrecht), in collabo- ration with the PHARMO Institute (Utrecht), the Netherlands Pharmacovigilance Centre Lareb (‘s-Hertogenbosch), the WHO-Uppsala Monitoring Centre (Uppsala, Sweden) and the Academic Medical Center (Amsterdam). The research presented in this thesis was funded by the Utrecht Institute for Pharmaceutical Sciences, and an unrestricted grant from the Dutch Medicines Evaluation Board. The study presented in chapter 3.1 was funded by an unrestricted grant from Janssen Pharmaceutica NV, Beerse, Belgium. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0024365A1 Vaya Et Al

US 2006.0024.365A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0024365A1 Vaya et al. (43) Pub. Date: Feb. 2, 2006 (54) NOVEL DOSAGE FORM (30) Foreign Application Priority Data (76) Inventors: Navin Vaya, Gujarat (IN); Rajesh Aug. 5, 2002 (IN)................................. 699/MUM/2002 Singh Karan, Gujarat (IN); Sunil Aug. 5, 2002 (IN). ... 697/MUM/2002 Sadanand, Gujarat (IN); Vinod Kumar Jan. 22, 2003 (IN)................................... 80/MUM/2003 Gupta, Gujarat (IN) Jan. 22, 2003 (IN)................................... 82/MUM/2003 Correspondence Address: Publication Classification HEDMAN & COSTIGAN P.C. (51) Int. Cl. 1185 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS A6IK 9/22 (2006.01) NEW YORK, NY 10036 (US) (52) U.S. Cl. .............................................................. 424/468 (22) Filed: May 19, 2005 A dosage form comprising of a high dose, high Solubility active ingredient as modified release and a low dose active ingredient as immediate release where the weight ratio of Related U.S. Application Data immediate release active ingredient and modified release active ingredient is from 1:10 to 1:15000 and the weight of (63) Continuation-in-part of application No. 10/630,446, modified release active ingredient per unit is from 500 mg to filed on Jul. 29, 2003. 1500 mg, a process for preparing the dosage form. Patent Application Publication Feb. 2, 2006 Sheet 1 of 10 US 2006/0024.365A1 FIGURE 1 FIGURE 2 FIGURE 3 Patent Application Publication Feb. 2, 2006 Sheet 2 of 10 US 2006/0024.365A1 FIGURE 4 (a) 7 FIGURE 4 (b) Patent Application Publication Feb. 2, 2006 Sheet 3 of 10 US 2006/0024.365 A1 FIGURE 5 100 ov -- 60 40 20 C 2 4. -

Partial Agreement in the Social and Public Health Field

COUNCIL OF EUROPE COMMITTEE OF MINISTERS (PARTIAL AGREEMENT IN THE SOCIAL AND PUBLIC HEALTH FIELD) RESOLUTION AP (88) 2 ON THE CLASSIFICATION OF MEDICINES WHICH ARE OBTAINABLE ONLY ON MEDICAL PRESCRIPTION (Adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 22 September 1988 at the 419th meeting of the Ministers' Deputies, and superseding Resolution AP (82) 2) AND APPENDIX I Alphabetical list of medicines adopted by the Public Health Committee (Partial Agreement) updated to 1 July 1988 APPENDIX II Pharmaco-therapeutic classification of medicines appearing in the alphabetical list in Appendix I updated to 1 July 1988 RESOLUTION AP (88) 2 ON THE CLASSIFICATION OF MEDICINES WHICH ARE OBTAINABLE ONLY ON MEDICAL PRESCRIPTION (superseding Resolution AP (82) 2) (Adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 22 September 1988 at the 419th meeting of the Ministers' Deputies) The Representatives on the Committee of Ministers of Belgium, France, the Federal Republic of Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, these states being parties to the Partial Agreement in the social and public health field, and the Representatives of Austria, Denmark, Ireland, Spain and Switzerland, states which have participated in the public health activities carried out within the above-mentioned Partial Agreement since 1 October 1974, 2 April 1968, 23 September 1969, 21 April 1988 and 5 May 1964, respectively, Considering that the aim of the Council of Europe is to achieve greater unity between its members and that this -

Quality Issues in Caring for Older People

Doctoral Thesis - Tesis Doctoral Quality issues in caring for older people: • Appropriateness of transition from long-term care facilities to acute hospital care • Potentially inappropriate medication: development of a European list Anna Renom Guiteras Prof. Gabriele Meyer Prof. Ramón Miralles Basseda Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Halle (Saale) & Barcelona, Catalonia University of Witten/Herdecke Spain Witten Germany Programa de doctorat en Medicina Departament de Medicina, Facultat de Medicina Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Barcelona, 2015 13 Contents 15 1. Introduction • Research context • Background of the research topics • Pesetaio of the ailes 23 2. Summary and discussion of the results 31 3. Conclusions 37 4. References 47 5. Articles • Article 1: Renom-Guiteras A, Uhrenfeldt L, Meyer G, Mann E. Assessment tools for determining appropriateness of admission to acute care of persons transferred from long-term care facilities: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:80 • Article 2: Renom-Guiteras A, Meyer G, Thürmann PA. The EU(7)-PIM list: a list of potentially inappropriate medications for older people consented by experts from seven European countries. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;71(7):861-75 77 6. Annexes • Annex 1.1 (article 1) - Additional file 1: Studies dealing with assessment tools for determining appropriateness of hospital admissions among residents of LTC facilities. • Annex 1.2 (article 1) - Additional file 2: Characteristics of the assessment tools for determining appropriateness of hospital admissions among residents of LTC facilities. • Annex 2.1 (article 2) - Appendix 1: Complete EU(7)-PIM list • Annex 2.2 (article 2) - Appendix 2: Questionable Potentially Inappropriate Medications (Questionable PIM): results of the Delphi survey.